Nomadic Matt's Travel Site

Travel Better, Cheaper, Longer

Why Tourists Ruin the Places They Visit

Last summer, while I was living in Sweden , I met up with travel writer Doug Lansky, the man behind several worldwide destination guides for Rough Guides. We were talking about travel (of course) and began discussing the philosophical question about whether, as traveler writers, we end up destroying the places we love by sharing them with the world.

By writing about those off-the-beaten-track destinations, those little local restaurants, and quiet parts of the city where you’re free of tourists, do we inadvertently contribute to the demise and overdevelopment of these destinations?

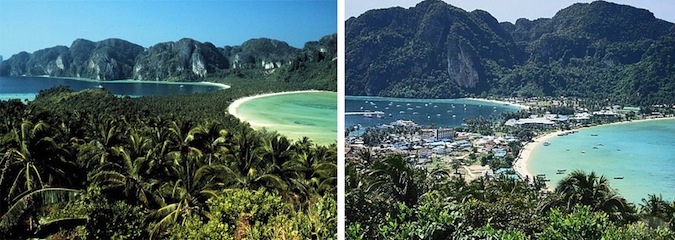

When I consider this question, I think about two things. First, I think about Tony Wheeler , the founder of Lonely Planet, the guy who pretty much commercialized backpacking. He’s the guy who turned the world onto Ko Phi Phi , which used to look like the left image and now looks like the right:

Secondly, I remember my own experience on Ko Lipe in Thailand (a tiny, out-of-the-way destination) and how overdeveloped that island has become in the last few years. Unfettered development has taken this tiny island and filled it with resorts and ruined coral reefs as drinking water needs to be pumped in from nearby islands to meet the needs.

And I think about how I always talk about Coral Bay, Australia — and other little towns and restaurants around the world — with great enthusiasm and encouragement. “Go there! They are wonderful and crowd free,” I proclaim.

By driving people to the next “undiscovered” place, do I just ruin it? Will I be that guy who returns and says, “Man, this place used to be cool 10 years ago.”

But, while not totally guiltless, I don’t think travel writers are to blame when destinations become crowded destinations full of tourists and overpriced hotels. (And, these days, there are a lot of factors that go into overtourism . It’s a complex — and urgent — problem!)

After ten years of traveling the world , I’ve come to realize that it’s the tourists themselves who ruin a destination.

And I don’t mean that simply because of the increase in visitors. I mean that because tourists end up supporting unsustainable tourism practices, and that’s what really destroys a place.

We simply love places to death.

Because, let’s face it, as a species, people are kind of assholes.

We can talk about sustainability and overtourism all we want but, if people really cared wouldn’t they stay in fewer Airbnbs, take fewer cruises, and try to avoid tours and animal tourism?

And then what happens?

You see many locals who are shortsighted and start building hotels, resorts, and businesses to try to cash in on the latest travel fad. And who can blame them? People need to eat, kids need to be sent to college, and money needs to be earned. The future is someone else’s problem, right? And I can’t really fault a lot of people for that. I don’t agree with that method of growth (not just in travel but in life in general), but how do you tell someone they can’t build something to feed their family?

I remember reading an article a few years back by Thomas Freidman from the New York Times talking about the rainforest in Brazil . In an interview, a local activist said that people need to eat, and, while most understand the need to protect the forest, with no alternative, people are going to choose food over protecting trees.

And it’s not just locals who do this.

Large corporations come in and take full advantage of lax regulation, low wages, and corrupt officials. Greenwashing , the practice of pretending you’re engaging in environmentally friendly actions, is very prevalent in travel.

(I think many countries in the world, including my own, should enact stronger environmental laws to help curb excessive building and development to ensure people take a longer view.)

Development is good, but unfettered development is bad and, unfortunately, there’s too much-unfettered development in tourism today.

But here’s why I put a lot of blame on visitors: As a writer, it’s important for me to not only highlight destinations (Go here! It’s great!), but to also emphasize responsibility so future generations can benefit from the place and enjoy it. There are a lot of great environmental travel blogs out there, and while this site deals more with the practical side of travel, I’ve talked about ruined places before and the need for better environmental protection many times .

But, as tourists, we ALSO have a responsibility to the destination. If we frequent operators, hotels, and services that are destructive — not only to the environment, but also to the local economy — we can’t really be surprised when we encounter mass development and “ruined,” overcrowded attractions.

How you spend your money is your vote for whether or not you accept what companies do. You know why companies have jumped on the eco-friendly bandwagon? Money. Sure, some actually care about the environment, but for 99% of them, it’s money.

People will pay more money if they feel like they’re positively impacting the environment. Wal-Mart executives are pretty open about the fact that they began selling eco-friendly and organic products because their customers were demanding it and there was money to be made.

I think the same is true in travel.

We have a choice in the vendors we use, the hotels we stay in, and the tour operators we hire. Our dollars go very far in developing countries, and the businesses there will change if we demand it. Start demanding good environmental practices and suddenly you’ll find them. If more and more people tell businesses that they want to see better environmental practices, they’ll happen.

You’ve found a company underpaying or mistreating their local staff? Or partaking in destructive practices? Let them know and use their competitors. There’s a lot of information online that can help you learn more about companies to avoid:

- Cruise Critic

- Green Global Travel Blog

- National Geographic Green Living Resources

I feel that many people, when given the right information, will make the right choice. And, as a travel writer, I’d like to encourage people to make that right choice. That means looking up the environmental record of the hotel or resort you’re staying in, choosing a tour company that is ecologically friendly, and avoiding destinations that are already overdeveloped. How do you do that? A little research and common sense.

But I can’t stop people from behaving badly when they get to a destination. I can just push them in the right direction.

If we push locals to be eco-friendly, they will. If writers push travelers to be eco-friendly, maybe they will. It’s a virtuous circle in which we all contribute.

We all bear some responsibility, but those whose money supports the ruinous ways bear the most.

It’s not the volume of travel that matters, but how that volume is handled. And we have a responsibility to ensure that the volume we create is well managed.

Or you could very well be the last person to see that destination in all of its splendor.

Book Your Trip: Logistical Tips and Tricks

Book Your Flight Find a cheap flight by using Skyscanner . It’s my favorite search engine because it searches websites and airlines around the globe so you always know no stone is being left unturned.

Book Your Accommodation You can book your hostel with Hostelworld . If you want to stay somewhere other than a hostel, use Booking.com as it consistently returns the cheapest rates for guesthouses and hotels.

Don’t Forget Travel Insurance Travel insurance will protect you against illness, injury, theft, and cancellations. It’s comprehensive protection in case anything goes wrong. I never go on a trip without it as I’ve had to use it many times in the past. My favorite companies that offer the best service and value are:

- SafetyWing (best for everyone)

- Insure My Trip (for those 70 and over)

- Medjet (for additional evacuation coverage)

Want to Travel for Free? Travel credit cards allow you to earn points that can be redeemed for free flights and accommodation — all without any extra spending. Check out my guide to picking the right card and my current favorites to get started and see the latest best deals.

Need Help Finding Activities for Your Trip? Get Your Guide is a huge online marketplace where you can find cool walking tours, fun excursions, skip-the-line tickets, private guides, and more.

Ready to Book Your Trip? Check out my resource page for the best companies to use when you travel. I list all the ones I use when I travel. They are the best in class and you can’t go wrong using them on your trip.

Photo of Ko Phi Phi thanks to the Traveling Canucks . It’s a great blog; you should read it.

Got a comment on this article? Join the conversation on Facebook , Instagram , or Twitter and share your thoughts!

Disclosure: Please note that some of the links above may be affiliate links, and at no additional cost to you, I earn a commission if you make a purchase. I recommend only products and companies I use and the income goes to keeping the site community supported and ad free.

Related Posts

Get my best stuff sent straight to you!

Pin it on pinterest.

Winter is here! Check out the winter wonderlands at these 5 amazing winter destinations in Montana

- Travel Tips

Why Tourists Ruin Places They Visit (and What You Can Do)

Published: November 11, 2023

Modified: December 28, 2023

by Frieda Shields

- Plan Your Trip

- Sustainability

Introduction

Traveling is a wonderful way to explore new places, experience different cultures, and create lasting memories. However, it’s no secret that tourism can have a negative impact on the destinations we visit. In recent years, the issue of overtourism has gained significant attention, with popular tourist hotspots becoming overcrowded and suffering from environmental degradation, destruction of cultural heritage, and economic exploitation.

As travelers, we have a responsibility to minimize our negative impact on the places we visit and strive for sustainable and responsible tourism. In this article, we will delve into the reasons why tourists can contribute to the ruination of the very destinations they admire. We will explore issues such as overcrowding, environmental degradation, destruction of cultural heritage, and economic exploitation, and provide practical tips on how to become a more responsible traveler.

By understanding the potential consequences of our actions and making conscious choices while traveling, we can help preserve the beauty and authenticity of the places we visit for future generations.

The Impact of Tourism on Local Destinations

Tourism can bring immense benefits to local economies, providing job opportunities and boosting revenue. However, the rapid growth of the tourism industry has also led to detrimental effects on the very destinations that attract millions of visitors each year.

One of the most significant impacts of tourism is overcrowding. Popular tourist destinations often experience an influx of visitors, leading to overcrowded streets, long queues, and crowded attractions. This not only creates inconvenience for both tourists and locals but also puts a strain on the infrastructure and public services of the destination. Overcrowding can result in increased pollution, traffic congestion, and inadequate waste management.

Another consequence of tourism is environmental degradation. Increased tourist activity can lead to the destruction of natural habitats, deforestation, pollution of air and water, and disturbance of fragile ecosystems. Negative impacts on flora and fauna can occur through irresponsible tourist behavior such as littering, damaging coral reefs during diving or snorkeling, and disturbing wildlife in protected areas.

In addition to environmental degradation, the preservation of cultural heritage is also at risk. Tourists often flock to destinations known for their historical landmarks, archaeological sites, and cultural traditions. However, the influx of visitors can result in the deterioration of these sites due to physical damage, overuse, or inappropriate behavior. Furthermore, the commercialization and commodification of cultural practices to cater to tourist demands can lead to the loss of authenticity and cultural identity.

Lastly, tourism can contribute to economic exploitation. In some cases, large multinational corporations dominate the tourism industry, controlling key establishments such as hotels, restaurants, and tour operators. Local businesses may struggle to compete, leading to a concentration of wealth in the hands of a few, while the majority of the local population does not benefit proportionately from the revenue generated by tourism.

It is essential to be aware of these impacts and take proactive steps to minimize our contribution to the negative consequences of tourism. In the next sections, we will explore practical ways to become a more responsible traveler and help mitigate the negative impacts of tourism.

Why Tourists Contribute to the Ruination of Places

While not all tourists intentionally cause harm to the destinations they visit, there are several reasons why their actions can contribute to the ruination of these places. Understanding these factors can help us make more conscious choices as travelers and work towards more sustainable tourism practices.

One of the main reasons is the sheer number of tourists. The rise in global tourism has led to overcrowding in many popular destinations. With more people wanting to explore the same locations, there is increased pressure on local infrastructure, natural resources, and cultural sites. As a result, the quality of the experience for both tourists and locals can deteriorate, affecting the overall attractiveness of the destination.

Furthermore, tourists may unwittingly engage in activities that harm the environment. Whether it’s leaving behind litter, disturbing wildlife, or contributing to pollution, these actions can have a cumulative negative impact on the ecosystem. For instance, in delicate natural areas such as coral reefs or national parks, heavy foot traffic and improper waste disposal can lead to irreversible damage.

In addition, tourists may not fully appreciate or respect the local culture and traditions. Cultural heritage plays a vital role in making a destination unique and authentic. However, some tourists may engage in disrespectful behavior, such as ignoring dress codes, taking inappropriate photographs, or participating in exploitative activities. This not only disrespects the local community but also erodes the cultural integrity of the destination.

Moreover, tourists contribute to the ruination of places through their spending habits. In some cases, tourists unknowingly support exploitative businesses that do not prioritize sustainability, fair labor practices, or community development. By choosing large multinational chains over locally-owned establishments, the economic benefits of tourism may not trickle down to the local community, exacerbating income inequality and ultimately harming the destination’s social and economic fabric.

While individual actions may seem inconsequential, the collective impact of millions of tourists engaging in these behaviors can lead to the ruination of once pristine and culturally-rich destinations. It is crucial for travelers to recognize their responsibility and take steps to minimize their negative impact, allowing future generations to continue enjoying these places.

Overcrowding and Overtourism

Overcrowding and overtourism have become pressing issues in many popular tourist destinations around the world. While tourism brings economic benefits, it can also lead to negative consequences when the number of visitors exceeds the carrying capacity of the destination.

Overcrowding is a result of the sheer volume of tourists, particularly in peak seasons. The influx of visitors can overwhelm the local infrastructure, creating bottlenecks in transportation, accommodation shortages, and overcrowded public spaces. This not only diminishes the quality of the experience for tourists but also disrupts the daily lives of local residents and can lead to tension and resentment.

Overtourism goes beyond overcrowding and encompasses a range of impacts on the destination. It can lead to the degradation of natural and cultural resources, increased pollution, and the loss of charm and authenticity. Tourist sites can become congested, making it difficult to fully appreciate their beauty and significance. The pressure on local resources, such as water and energy, may exceed their capacity, posing environmental risks.

Overtourism can also result in the phenomenon of “touristification,” where destinations become solely focused on catering to tourists and lose their genuine character. Local businesses may prioritize catering to the demands of tourists over meeting the needs of the local community, leading to a loss of traditional practices and authentic experiences.

There are several contributing factors to overcrowding and overtourism. The rise of budget airlines, online travel information, and the growing middle class in many countries have made travel more accessible and affordable. The concentration of tourist activity in specific locations, often due to limited marketing efforts or lack of infrastructure development in other areas, further exacerbate the problem.

To address the issue of overcrowding and promote more sustainable tourism practices, destinations may implement strategies such as implementing visitor quotas, managing tourist flows through time-ticketing systems, and diversifying tourism offerings to distribute visitors more evenly. These measures aim to balance the economic benefits of tourism with the preservation of the natural and cultural integrity of the destination.

As responsible travelers, we can also play a part in combating overcrowding and overtourism. By choosing to visit lesser-known destinations or traveling during off-peak periods, we can help alleviate the pressure on popular tourist hotspots. It is essential to respect local regulations, follow appropriate codes of conduct, and be mindful of the impact our presence has on the destination and the local communities.

By addressing the challenges of overcrowding and overtourism, we can ensure that both current and future generations can continue to enjoy the beauty and authenticity of the places we visit without compromising their sustainability.

Environmental Degradation

One of the significant impacts of tourism is environmental degradation. The rise in tourist activity can have detrimental effects on natural ecosystems, contributing to the loss of biodiversity, pollution, and the destruction of delicate habitats.

Tourists often flock to pristine natural areas, attracted by their beauty and unique ecosystems. However, the increased foot traffic and improper behavior can lead to erosion, soil compaction, and damage to vegetation, affecting the delicate balance of the ecosystem. Activities such as off-road driving, littering, and unauthorized camping can lead to irreparable harm to sensitive environments.

Marine environments, such as coral reefs, are particularly vulnerable to the negative impacts of tourism. Activities such as anchoring boats, careless diving practices, and improper disposal of chemicals and waste can lead to the destruction of coral reefs, which are essential habitats for numerous marine species. Overfishing and illegal harvesting of marine life for the tourist trade further threaten the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

The increase in infrastructure development to accommodate the growing number of tourists can also contribute to environmental degradation. Construction of hotels, resorts, and other tourist facilities often involves clearing natural habitats, leading to deforestation and habitat loss for many species. Additionally, the demand for water resources by tourists can strain local supplies, putting pressure on limited freshwater sources and impacting the availability of water for local communities and ecosystems.

Pollution is another significant environmental concern associated with tourism. The increase in air and water pollution from transportation, waste generation, and energy consumption associated with tourism activities can have long-term negative consequences. Air pollution from transportation emissions contributes to climate change and affects air quality in tourist destinations. Improper waste management, such as the disposal of non-biodegradable items, can lead to contamination of land and water bodies, further impacting the local environment.

To mitigate environmental degradation from tourism, sustainable practices are crucial. Choosing eco-friendly transportation options, such as public transportation or cycling, can help reduce carbon emissions. Opting for accommodations that implement sustainable practices, such as water and energy conservation, waste recycling, and utilizing renewable energy sources, can significantly minimize environmental impact.

Responsible travel behavior includes following designated trails, respecting wildlife and their habitats, and adhering to waste reduction and recycling practices. Engaging in outdoor activities, such as hiking and snorkeling, with certified guides who prioritize conservation and responsible behavior ensures that you have a minimal impact on the natural environment.

Ultimately, preserving the natural environment is essential for the long-term sustainability and enjoyment of tourism. By being mindful of our actions and making environmentally conscious choices, we can minimize the negative impacts of tourism on the natural world and contribute to its preservation for future generations.

Destruction of Cultural Heritage

When it comes to tourism, cultural heritage plays a significant role in attracting visitors to a destination. However, the very influx of tourists can lead to the destruction and degradation of cultural sites and practices, ultimately eroding the authenticity and integrity of the local culture.

One of the primary causes of the destruction of cultural heritage is irresponsible tourist behavior. Some visitors may engage in activities that physically damage cultural sites or artifacts. Touching, climbing on, or defacing historical structures, statues, or artwork can cause irreparable harm. Moreover, the use of flash photography or improper handling of artifacts can accelerate their deterioration.

The commercialization and commodification of cultural practices also contribute to the destruction of cultural heritage. In an attempt to meet tourist demands, some communities may alter their traditions or perform them solely for entertainment purposes. This can result in the loss of cultural authenticity as traditions become diluted or staged purely for commercial gain.

Tourism can also lead to the displacement of local communities and disruption of traditional ways of life. As tourist infrastructure expands, local residents may be coerced into selling their properties or changing their livelihoods to cater to the tourism market. This erodes the social fabric of the community and can lead to the loss of generational knowledge and traditional practices.

Furthermore, the concentration of tourism activity in specific areas can create overcrowding and intense pressure on cultural sites. Increased foot traffic, improper waste management, and inadequate preservation measures can lead to the physical degradation of these sites over time.

To minimize the destruction of cultural heritage, it is important for tourists to approach these sites and experiences with respect and an understanding of their significance. Following established rules and regulations, such as avoiding prohibited areas, refraining from touching or damaging artifacts, and adhering to appropriate dress codes, helps protect cultural sites and practices.

Supporting responsible tourism initiatives that seek to preserve and promote cultural heritage is also crucial. This may include attending cultural performances that prioritize the preservation of authentic traditions, purchasing locally-made crafts and products, and supporting community-based tourism initiatives that involve local residents in sharing their culture and heritage with visitors.

Visitors can also educate themselves about the cultural significance of the places they are visiting. Learning about the history, traditions, and stories behind cultural sites allows for a deeper appreciation and respect for the destination. Additionally, engaging with local communities and seeking their perspectives can provide valuable insights into the importance of preserving and respecting cultural heritage.

By taking these actions, tourists can help preserve and protect cultural heritage, ensuring that future generations can continue to appreciate and learn from these invaluable aspects of our shared human history.

Economic Exploitation

Although tourism has the potential to bring economic benefits to local communities, it can also lead to economic exploitation, particularly when the benefits are not evenly distributed or when large multinational corporations dominate the tourism industry.

In some destinations, the tourism industry is controlled by a few powerful entities, such as multinational hotel chains or tour operators. This concentration of power often results in limited economic opportunities for local businesses. Small, locally-owned accommodations and establishments may struggle to compete, leading to a concentration of wealth in the hands of a few while the majority of the local population does not benefit proportionately from the revenue generated by tourism.

Furthermore, the demand for cheap labor in the tourism sector can lead to low wages and poor working conditions for local employees. Large hotels and resorts may seek to cut costs by employing staff on minimum wages or hiring migrant workers who may not have the same labor protections as local citizens.

Additionally, the establishment of tourist infrastructure and amenities often prioritizes the needs and desires of tourists over those of the local community. This can lead to increases in the cost of living, pushing locals out of their own neighborhoods or making it unaffordable for them to access essential goods and services.

The economic imbalance can also result in leakage, where a significant portion of the tourism revenue leaves the destination. This can occur when multinational corporations repatriate profits to their home countries, or when a substantial portion of tourist expenditures goes toward international-owned businesses and services. As a result, the local community sees limited direct financial benefit from tourism.

To address economic exploitation in tourism, it is crucial to support local businesses and initiatives that prioritize community development and empowerment. By seeking out locally-owned accommodations, restaurants, and tour operators, travelers can contribute directly to the local economy and ensure that a larger share of the tourism revenue remains within the community.

Engaging in fair and ethical tourism is also important. This includes supporting initiatives that promote fair wages and good working conditions for employees, as well as those that prioritize environmental sustainability and community involvement.

Furthermore, responsible travelers can seek out meaningful interactions with the local community, such as participating in cultural exchanges or purchasing locally-made products. By engaging in community-based tourism initiatives, travelers can directly contribute to local income generation and support the preservation of local culture and traditions.

Ultimately, promoting a more equitable distribution of tourism benefits involves a collective effort from all stakeholders, including governments, businesses, and travelers. By being conscious consumers and supporting initiatives that prioritize local empowerment and economic development, we can contribute to a more inclusive and sustainable tourism industry.

Responsible Tourism: What Can You Do?

As travelers, we have the power to make a positive impact and contribute to responsible tourism practices. By being mindful of our actions and making conscious choices, we can help minimize the negative impacts of tourism and ensure a more sustainable and enjoyable travel experience. Here are some practical steps you can take:

Choose Sustainable Accommodation: Opt for eco-friendly accommodations that implement sustainable practices, such as recycling, energy and water conservation, and use of renewable energy sources. Look for certifications or labels that indicate a commitment to sustainability, such as LEED certification or eco-friendly hotel certifications.

Support Local Businesses: Seek out locally-owned establishments, such as restaurants, shops, and tour operators. By supporting local businesses, you can help to ensure that the economic benefits of tourism reach the local community and contribute to its development. Also, consider purchasing locally-made products and souvenirs to directly support local artisans and craftspeople.

Respect the Local Culture and Traditions: Educate yourself about the local customs and traditions of the places you visit. Show respect by dressing appropriately, following local customs, and seeking permission before taking photographs, particularly at religious or sacred sites. Avoid participating in activities that exploit or commodify the local culture and instead engage in authentic and respectful cultural experiences.

Be Mindful of the Environment: Practice responsible behavior towards the environment by minimizing waste, conserving water and energy, and properly disposing of trash. Follow designated trails, respect wildlife and their habitats, and choose eco-friendly transportation options whenever possible. Consider offsetting your carbon footprint by participating in carbon offset programs.

Engage in Community-Based Tourism: Seek out opportunities to interact with local communities and learn from their experiences. Participate in community-based tourism initiatives that engage and empower local residents, ensuring that they have a say in tourism development. This can include homestays, guided tours led by locals, or participating in community-led projects that aim to preserve cultural heritage and protect the natural environment.

Spread Awareness: Share your knowledge and experiences with others to promote responsible tourism practices. Encourage friends, family, and fellow travelers to make conscious choices and be mindful of their impact on the places they visit. Use social media or travel blogs to inspire and educate others about sustainable travel practices.

By taking these steps, we can contribute to the preservation of the destinations we love and ensure that they remain vibrant, authentic, and accessible for future generations. Responsible tourism starts with each individual traveler, and together we can make a significant difference in creating a more sustainable and harmonious travel experience.

Choose Sustainable Accommodation

When planning your travel accommodations, one essential aspect of responsible tourism is choosing sustainable options. By selecting eco-friendly and socially responsible accommodations, you can minimize your environmental impact and support businesses that prioritize sustainability. Here are some key considerations when choosing sustainable accommodation:

Look for certifications and labels: Check for recognized certifications or labels that indicate a commitment to sustainability. These may include LEED certification, Green Key, or eco-friendly hotel certifications. These certifications often require meeting specific criteria related to energy and water conservation, waste management, and environmentally-friendly practices.

Consider the location: Opt for accommodations that are located in close proximity to the areas you plan to explore or that have good access to public transportation. This reduces the need for additional transportation and minimizes carbon emissions. Additionally, staying in smaller, locally-owned establishments in rural or less crowded areas can help promote the economic development of these communities.

Assess energy and water conservation: Sustainable accommodations prioritize energy and water conservation. Look for hotels that use energy-efficient lighting and appliances, implement water-saving measures such as low-flow showerheads and toilets, and utilize renewable energy sources. These practices help to minimize resource consumption and reduce the environmental footprint of the accommodation.

Waste management and recycling: Inquire about the accommodation’s waste management practices. Sustainable accommodations often have recycling programs in place and prioritize waste reduction. Look for facilities that provide opportunities for guests to separate and recycle their waste properly.

Support local and organic food: Choose accommodations that offer locally sourced and organic food options. Supporting local farmers and reducing the carbon footprint associated with food transportation are key elements of sustainable tourism. Some accommodations even have their own on-site gardens or work with local producers to ensure fresh and sustainable meals for their guests.

Community involvement and social responsibility: Consider accommodations that engage in community-based initiatives and support local communities. These establishments often hire locally, provide fair wages and good working conditions for their employees, and actively contribute to the social and economic development of their surrounding communities.

Alternative accommodation options: Consider alternative accommodation options, such as eco-lodges, guesthouses, or homestays, which are often owned and operated by local residents. These accommodations offer a more personal and authentic experience while supporting the local economy directly.

By consciously selecting sustainable accommodation options, you can contribute to the preservation of the environment and support local communities. Your choices as a responsible traveler can help create a more sustainable tourism industry and demonstrate the demand for eco-friendly and socially responsible practices.

Support Local Businesses

When traveling, one of the most impactful ways to contribute to the local economy and promote responsible tourism is by supporting local businesses. By patronizing locally-owned establishments, you can help to ensure that the economic benefits of tourism go directly to the local community. Here are some key reasons why supporting local businesses is important:

Community Development: Supporting local businesses helps to foster economic development within the community. These establishments provide employment opportunities for local residents, which in turn, improves the livelihoods of individuals and contributes to the overall well-being of the community. By spending your money at local businesses, you are directly supporting the local workforce and helping to create a sustainable economic ecosystem.

Promoting Cultural Authenticity: Local businesses often reflect the unique culture, traditions, and flavors of a destination. By opting for local restaurants, shops, and markets, you’ll have the opportunity to engage with the local community and experience the authentic flavors, crafts, and customs of the region. Supporting these businesses helps to preserve and promote the cultural heritage of the destination, ensuring that it retains its distinct identity and charm.

Sustainability and Fair Trade: Local businesses are more likely to prioritize sustainable practices and support fair trade. They often source their products locally, reducing the carbon footprint associated with transportation and supporting local producers. By purchasing locally-made products, you encourage sustainability and contribute to the local economy rather than supporting mass-produced, imported goods.

Personalized Experiences: Local businesses tend to offer personalized and unique experiences that larger chain establishments often cannot provide. Whether it’s staying at a family-run guesthouse, booking a tour with a local guide, or dining at a neighborhood restaurant, you’re likely to have a more authentic and enriching experience. Local business owners have a deep knowledge and understanding of the area, allowing them to offer insights and recommendations that enhance your overall travel experience.

Preservation of Local Character: By supporting local businesses, you help to maintain the distinct character and charm of a destination. Instead of contributing to the homogenization of tourism, where destinations become overly commercialized and lose their authenticity, your support enables local businesses to thrive and continue their unique contributions to the local community.

Spreading Economic Benefits: When you spend your money at local businesses, a higher percentage of the revenue remains within the local community. This allows the economic benefits of tourism to trickle down to more individuals and sectors, fostering a more inclusive and equitable distribution of wealth.

By consciously supporting local businesses, you become an active participant in the local economy, ensuring that your travel experiences have a positive impact. Take the time to explore local markets, dine at family-owned establishments, and choose locally-owned accommodations. Through these choices, you can help create sustainable and vibrant communities while gaining a richer and more authentic travel experience.

Respect the Local Culture and Traditions

When traveling, it is essential to respect the local culture and traditions of the places you visit. By being mindful and respectful of the customs and practices of the local community, you can foster cultural understanding, preserve the authenticity of the destination, and ensure positive interactions with locals. Here are some key considerations when it comes to respecting the local culture and traditions:

Do your research: Before visiting a new destination, take the time to learn about the local customs, traditions, and social norms. Familiarize yourself with any cultural practices or dress codes that may be different from your own. Understanding the cultural context will help you navigate the destination with sensitivity and respect.

Dress appropriately: Respect local dress codes, especially when visiting religious sites or conservative communities. Modest clothing is often required, which may include covering shoulders, chest, and legs. By dressing appropriately, you show respect for the local customs and avoid causing offense or discomfort.

Observe and follow local customs: Pay attention to local customs and norms and follow them accordingly. This can include practices such as removing shoes before entering someone’s home, greeting others in a specific manner, or refraining from public displays of affection. Being observant and respectful of these customs will help create positive interactions and show your appreciation for the local culture.

Ask for permission: When taking photographs, especially of people, always ask for permission first. Respect the privacy of individuals and sacred places. Some attractions or cultural sites may have specific rules about photography, so be sure to adhere to them.

Engage in cultural activities responsibly: Participate in cultural activities or performances with respect and sensitivity. Be mindful of the context and significance of the activity, and avoid supporting or participating in practices that exploit or misrepresent the local culture. Seek out authentic and ethical experiences that involve local communities and support their traditions in a sustainable and respectful manner.

Learn basic local phrases: Making an effort to learn a few basic phrases in the local language can go a long way. Even simple greetings or expressions of gratitude can demonstrate your respect for the local culture and make interactions more meaningful.

Show appreciation, not appropriation: Respect the difference between appreciating and appropriating the local culture. Appreciation involves understanding, learning from, and showing respect for the culture, while appropriation involves borrowing or adopting elements of a culture without proper understanding or respect. Avoid practices such as wearing traditional cultural attire as costumes or using sacred symbols without understanding their significance.

Listen and learn: Engage in conversations with locals and be open to learning from them. Ask questions, show genuine curiosity, and be respectful of their perspectives and experiences. Being a respectful traveler involves being open-minded and embracing opportunities to broaden your cultural understanding.

By respecting and embracing the local culture and traditions, you not only enhance your own travel experience but also contribute to the preservation and appreciation of the local heritage. Recognize that you are a guest in the destination and act with humility, showing respect for the uniqueness of the local culture and the individuals who call it home.

Be Mindful of the Environment

Being mindful of the environment is a crucial aspect of responsible tourism. By minimizing our environmental impact while traveling, we can help preserve the natural beauty and ecological balance of the destinations we visit. Here are some key considerations to be mindful of the environment:

Reduce waste: Reduce your waste generation by opting for reusable alternatives whenever possible. Carry a reusable water bottle, shopping bag, and utensils to avoid single-use plastics. Dispose of waste properly in designated recycling or compost bins and follow local waste management guidelines.

Conserve water and energy: Conserve precious resources by being mindful of your water and energy use. Take shorter showers, report leaks in accommodation facilities, turn off lights and air conditioning when leaving your room, and unplug electronic devices when not in use. Be aware of your consumption and strive to minimize your ecological footprint.

Respect wildlife: Observe wildlife in their natural habitats from a respectful distance. Do not feed, touch, or disrupt animals, as this can cause stress and harm to their behavior and well-being. Follow designated trails and adhere to guidelines for wildlife encounters to minimize your impact.

Choose eco-friendly transportation: Opt for eco-friendly transportation options whenever possible. Consider using public transportation, cycling, or walking to explore destinations. If you must use a vehicle, consider carpooling or renting fuel-efficient or electric vehicles. Additionally, offsetting your carbon emissions through recognized programs can help reduce your travel’s environmental impact.

Support sustainable tour operators: Choose tour operators or guides who prioritize sustainable practices and responsible wildlife encounters. Look for those who observe ethical guidelines, promote conservation efforts, and support local communities. Responsible operators will prioritize the well-being and preservation of the environment in their activities.

Leave nature as you found it: When hiking, camping, or engaging in outdoor activities, leave no trace. Respect natural areas by taking any waste or litter with you, sticking to designated trails, and refraining from disturbing plants or wildlife. Let the beauty of nature inspire you, but ensure it remains unspoiled for others to enjoy.

Support environmental initiatives: Seek out and support local environmental initiatives, whether it’s participating in beach clean-ups, volunteering for conservation organizations, or donating to local environmental projects. These efforts contribute directly to the preservation and restoration of natural landscapes and habitats.

Choose eco-friendly accommodations: Look for accommodations that prioritize sustainability. Choose establishments that implement energy and water conservation measures, utilize renewable energy sources, and have waste management and recycling programs in place. Eco-lodges, hotels with green certifications, or accommodations with eco-friendly initiatives are excellent choices.

By being mindful of the environment, we can leave a positive impact while exploring the world. Our actions as responsible travelers can contribute to the preservation of fragile ecosystems, protect wildlife, and ensure the longevity of the natural wonders that inspire us to travel. Together, we can make a difference in creating a more sustainable and harmonious relationship between tourism and the environment.

Engage in Community-Based Tourism

Engaging in community-based tourism is a meaningful way to connect with local communities, support their development, and promote sustainable and responsible travel. It involves actively participating in activities and initiatives that involve and benefit the local residents. Here are some reasons why community-based tourism is important and how you can engage in it:

Promoting Local Empowerment: Community-based tourism empowers local communities by providing them with economic opportunities and allowing them to take control of their own tourism development. By participating in community-led initiatives, you directly contribute to the well-being and economic growth of the local residents.

Cultural Exchange and Authentic Experiences: Engaging in community-based tourism allows for authentic cultural exchange. You will have the opportunity to interact with locals, participate in their daily activities, learn about their traditions, and gain a deeper understanding of their way of life. This cultural immersion provides a richer travel experience and fosters mutual respect and appreciation.

Preserving Cultural Heritage: Community-based tourism helps preserve cultural heritage by supporting the continuation of local crafts, performing arts, and traditional practices. By participating in activities such as traditional cooking classes, handicraft workshops, or guided village tours, you contribute to the preservation and promotion of these cultural traditions.

Supporting Sustainable Development: Community-based tourism often prioritizes sustainability and environmental stewardship. Initiatives may include sustainable farming practices, protection of local ecosystems, and the use of renewable energy sources. By engaging in these activities, you contribute to the conservation of natural resources and the protection of the environment.

Creating Economic Opportunities: By choosing community-based tourism, you support local businesses and artisans. Stay at locally-owned guesthouses or homestays, eat at local restaurants, and purchase locally-made crafts and products. This ensures that a larger share of the revenue generated from tourism stays within the community and benefits its members directly.

Participating in Volunteering and Skill-Sharing: Engaging in community-based tourism can also involve volunteering or skill-sharing opportunities. You can contribute your skills, knowledge, or time to community projects such as environmental conservation, education, or community development initiatives. This allows you to actively give back to the community and develop a deeper connection with the local residents.

Respecting Local Customs and Traditions: When engaging in community-based tourism, it is important to respect the local customs and traditions. Be open-minded, embrace cultural differences, and follow cultural protocols. Seek guidance from community leaders or guides to ensure that your participation is respectful and in line with local customs.

Remember, community-based tourism involves forming genuine connections and building relationships with the local community. Take the time to listen, learn, and understand the perspectives and aspirations of the community members. By engaging in community-based tourism, you contribute to the sustainable development and preservation of the local culture, heritage, and environment.

In conclusion, responsible tourism is crucial for preserving the destinations we love and ensuring their longevity for future generations. By understanding the negative impacts of tourism, such as overcrowding, environmental degradation, destruction of cultural heritage, and economic exploitation, we can make informed choices to minimize our contribution to these issues.

Choosing sustainable accommodation, supporting local businesses, respecting the local culture and traditions, being mindful of the environment, and engaging in community-based tourism are key ways to promote responsibility. These actions not only benefit the local community and environment but also enhance our own travel experiences by fostering authentic connections and preserving the cultural authenticity of the places we visit.

As responsible travelers, we have the power to make a positive impact. By supporting local initiatives, participating in sustainable activities, and embracing cultural diversity, we contribute to the preservation of our planet’s natural and cultural treasures.

Let us remember that responsible tourism is an ongoing commitment. It is about being mindful of our choices and continuously striving to minimize our negative impact while maximizing the positive contributions we can make. By practicing responsible tourism, we can ensure that our travels leave a legacy of sustainability, cultural preservation, and economic empowerment for the destinations and communities we encounter along the way.

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

A Year Without Travel

For Planet Earth, No Tourism Is a Curse and a Blessing

From the rise in poaching to the waning of noise pollution, travel’s shutdown is having profound effects. Which will remain, and which will vanish?

By Lisa W. Foderaro

For the planet, the year without tourists was a curse and a blessing.

With flights canceled, cruise ships mothballed and vacations largely scrapped, carbon emissions plummeted. Wildlife that usually kept a low profile amid a crush of tourists in vacation hot spots suddenly emerged. And a lack of cruise ships in places like Alaska meant that humpback whales could hear each other’s calls without the din of engines.

That’s the good news. On the flip side, the disappearance of travelers wreaked its own strange havoc, not only on those who make their living in the tourism industry, but on wildlife itself, especially in developing countries. Many governments pay for conservation and enforcement through fees associated with tourism. As that revenue dried up, budgets were cut, resulting in increased poaching and illegal fishing in some areas. Illicit logging rose too, presenting a double-whammy for the environment. Because trees absorb and store carbon, cutting them down not only hurt wildlife habitats, but contributed to climate change.

“We have seen many financial hits to the protection of nature,” said Joe Walston, executive vice president of global conservation at the Wildlife Conservation Society. “But even where that hasn’t happened, in a lot of places people haven’t been able to get into the field to do their jobs because of Covid.”

From the rise in rhino poaching in Botswana to the waning of noise pollution in Alaska, the lack of tourism has had a profound effect around the world. The question moving forward is which impacts will remain, and which will vanish, in the recovery.

A change in the air

While the pandemic’s impact on wildlife has varied widely from continent to continent, and country to country, its effect on air quality was felt more broadly.

In the United States, greenhouse gas emissions last year fell more than 10 percent , as state and local governments imposed lockdowns and people stayed home, according to a report in January by the Rhodium Group, a research and consulting firm.

The most dramatic results came from the transportation sector, which posted a 14.7 percent decrease. It’s impossible to tease out how much of that drop is from lost tourism versus business travel. And there is every expectation that as the pandemic loosens its grip, tourism will resume — likely with a vengeance.

Still, the pandemic helped push American emissions below 1990 levels for the first time. Globally, carbon dioxide emissions fell 7 percent , or 2.6 billion metric tons, according to new data from international climate researchers. In terms of output, that is about double the annual emissions of Japan.

“It’s a lot and it’s a little,” said Jason Smerdon, a climate scientist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory . “Historically, it’s a lot. It’s the largest single reduction percent-wise over the last 100 years. But when you think about the 7 percent in the context of what we need to do to mitigate climate change, it’s a little.”

In late 2019, the United Nations Environment Program cautioned that global greenhouse gases would need to drop 7.6 percent every year between 2020 and 2030. That would keep the world on its trajectory of meeting the temperature goals set under the Paris Agreement, the 2016 accord signed by nearly 200 nations.

“The 7 percent drop last year is on par with what we would need to do year after year,” Dr. Smerdon said. “Of course we wouldn’t want to do it the same way. A global pandemic and locking ourselves in our apartments is not the way to go about this.”

Interestingly, the drop in other types of air pollution during the pandemic muddied the climate picture. Industrial aerosols, made up of soot, sulfates, nitrates and mineral dust, reflect sunlight back into space, thus cooling the planet. While their reduction was good for respiratory health, it had the effect of offsetting some of the climate benefits of cascading carbon emissions.

For the climate activist Bill McKibben , one of the first to sound the alarm about global warming in his 1989 book, “The End of Nature,” the pandemic underscored that the climate crisis won’t be averted one plane ride or gallon of gas at a time.

“We’ve come through this pandemic year when our lives changed more than any of us imagined they ever would,” Mr. McKibben said during a Zoom webinar hosted in February by the nonprofit Green Mountain Club of Vermont.

“Everybody stopped flying; everybody stopped commuting,” he added. “Everybody just stayed at home. And emissions did go down, but they didn’t go down that much, maybe 10 percent with that incredible shift in our lifestyles. It means that most of the damage is located in the guts of our systems and we need to reach in and rip out the coal and gas and oil and stick in the efficiency, conservation and sun and wind.”

Wildlife regroups

Just as the impact of the pandemic on air quality is peppered with caveats, so too is its influence on wildlife.

Animals slithered, crawled and stomped out of hiding across the globe, sometimes in farcical fashion. Last spring, a herd of Great Orme Kashmiri goats was spotted ambling through empty streets in Llandudno, a coastal town in northern Wales. And hundreds of monkeys — normally fed by tourists — were involved in a disturbing brawl outside of Bangkok, apparently fighting over food scraps.

In meaningful ways, however, the pandemic revealed that wildlife will regroup if given the chance. In Thailand, where tourism plummeted after authorities banned international flights, leatherback turtles laid their eggs on the usually mobbed Phuket Beach. It was the first time nests were seen there in years, as the endangered sea turtles, the largest in the world, prefer to nest in seclusion.

Similarly, in Koh Samui, Thailand’s second largest island, hawksbill turtles took over beaches that in 2018 hosted nearly three million tourists. The hatchlings were documented emerging from their nests and furiously moving their flippers toward the sea.

For Petch Manopawitr, a marine conservation manager of the Wildlife Conservation Society Thailand, the sightings were proof that natural landscapes can recover quickly. “Both Ko Samui and Phuket have been overrun with tourists for so many years,” he said in a phone interview. “Many people had written off the turtles and thought they would not return. After Covid, there is talk about sustainability and how it needs to be embedded in tourism, and not just a niche market but all kinds of tourism.”

In addition to the sea turtles, elephants, leaf monkeys and dugongs (related to manatees) all made cameos in unlikely places in Thailand. “Dugongs are more visible because there is less boat traffic,” Mr. Manopawitr said. “The area that we were surprised to see dugongs was the eastern province of Bangkok. We didn’t know dugongs still existed there.”

He and other conservationists believe that countries in the cross hairs of international tourism need to mitigate the myriad effects on the natural world, from plastic pollution to trampled parks.

That message apparently reached the top levels of the Thai government. In September, the nation’s natural resources and environment minister, Varawut Silpa-archa, said he planned to shutter national parks in stages each year, from two to four months. The idea, he told Bloomberg News , is to set the stage so that “nature can rehabilitate itself.”

An increase in poaching

In other parts of Asia and across Africa, the disappearance of tourists has had nearly the opposite result. With safari tours scuttled and enforcement budgets decimated, poachers have plied their nefarious trade with impunity. At the same time, hungry villagers have streamed into protected areas to hunt and fish.

There were reports of increased poaching of leopards and tigers in India, an uptick in the smuggling of falcons in Pakistan, and a surge in trafficking of rhino horns in South Africa and Botswana.

Jim Sano, the World Wildlife Fund’s vice president for travel, tourism and conservation, said that in sub-Saharan Africa, the presence of tourists was a powerful deterrent. “It’s not only the game guards,” he said. “It’s the travelers wandering around with the guides that are omnipresent in these game areas. If the guides see poachers with automatic weapons, they report it.”

In the Republic of Congo, the Wildlife Conservation Society has noticed an increase in trapping and hunting in and around protected areas. Emma J. Stokes, regional director of the Central Africa program for the organization, said that in Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park, monkeys and forest antelopes were being targeted for bushmeat.

“It’s more expensive and difficult to get food during the pandemic and there is a lot of wildlife up there,” she said by phone. “We obviously want to deter people from hunting in the park, but we also have to understand what’s driving that because it’s more complex.”

The Society and the Congolese government jointly manage the park, which spans 1,544 square miles of lowland rainforest — larger than Rhode Island. Because of the virus, the government imposed a national lockdown, halting public transportation. But the organization was able to arrange rides to markets since the park is considered an essential service. “We have also kept all 300 of our park staff employed,” she added.

Largely absent: the whir of propellers, the hum of engines

While animals around the world were subject to rifles and snares during the pandemic, one thing was missing: noise. The whir of helicopters diminished as some air tours were suspended. And cruise ships from the Adriatic Sea to the Gulf of Mexico were largely absent. That meant marine mammals and fish had a break from the rumble of engines and propellers.

So did research scientists. Michelle Fournet is a marine ecologist who uses hydrophones (essentially aquatic microphones) to listen in on whales. Although the total number of cruise ships (a few hundred) pales in comparison to the total number of cargo ships (tens of thousands), Dr. Fournet says they have an outsize role in creating underwater racket. That is especially true in Alaska, a magnet for tourists in search of natural splendor.

“Cargo ships are trying to make the most efficient run from point A to point B and they are going across open ocean where any animal they encounter, they encounter for a matter of hours,” she said. “But when you think about the concentration of cruise ships along coastal areas, especially in southeast Alaska, you basically have five months of near-constant vessel noise. We have a population of whales listening to them all the time.”

Man-made noise during the pandemic dissipated in the waters near the capital of Juneau, as well as in Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve . Dr. Fournet, a postdoctoral research associate at Cornell University, observed a threefold decrease in ambient noise in Glacier Bay between 2019 and 2020. “That’s a really big drop in noise,” she said, “and all of that is associated with the cessation of these cruise ships.”

Covid-19 opened a window onto whale sounds in Juneau as well. Last July, Dr. Fournet, who also directs the Sound Science Research Collective , a marine conservation nonprofit, had her team lower a hydrophone in the North Pass, a popular whale-watching destination. “In previous years,” she said, “you wouldn’t have been able to hear anything — just boats. This year we heard whales producing feeding calls, whales producing contact calls. We heard sound types that I have never heard before.”

Farther south in Puget Sound, near Seattle, whale-watching tours were down 75 percent last year. Tour operators like Jeff Friedman, owner of Maya’s Legacy Whale Watching , insist that their presence on the water benefits whales since the captains make recreational boaters aware of whale activity and radio them to slow down. Whale-watching companies also donate to conservation groups and report sightings to researchers.

“During the pandemic, there was a huge increase in the number of recreational boats out there,” said Mr. Friedman, who is also president of the Pacific Whale Watch Association . “It was similar to R.V.s. People decided to buy an R.V. or a boat. The majority of the time, boaters are not aware that the whales are present unless we let them know.”

Two years ago, in a move to protect Puget Sound’s tiny population of Southern Resident killer whales, which number just 75, Washington’s Gov. Jay Inslee signed a law reducing boat speeds to 7 knots within a half nautical mile of the whales and increasing a buffer zone around them, among other things.

Many cheered the protections. But environmental activists like Catherine W. Kilduff, a senior attorney in the oceans program at the Center for Biological Diversity, believe they did not go far enough. She wants the respite from noise that whales enjoyed during the pandemic to continue.

“The best tourism is whale-watching from shore,” she said.

Looking Ahead

Debates like this are likely to continue as the world emerges from the pandemic and leisure travel resumes. Already, conservationists and business leaders are sharing their visions for a more sustainable future.

Ed Bastian, Delta Air Lines’ chief executive, last year laid out a plan to become carbon neutral by spending $1 billion over 10 years on an assortment of strategies. Only 2.5 percent of global carbon emissions are traced to aviation, but a 2019 study suggested that could triple by midcentury.

In the meantime, climate change activists are calling on the flying public to use their carbon budgets judiciously.

Tom L. Green, a senior climate policy adviser with the David Suzuki Foundation , an environmental organization in Canada, said tourists might consider booking a flight only once every few years, saving their carbon footprint (and money) for a special journey. “Instead of taking many short trips, we could occasionally go away for a month or more and really get to know a place,” he said.

For Mr. Walston of the Wildlife Conservation Society, tourists would be wise to put more effort into booking their next resort or cruise, looking at the operator’s commitment to sustainability.

“My hope is not that we stop traveling to some of these wonderful places, because they will continue to inspire us to conserve nature globally,” he said. “But I would encourage anyone to do their homework. Spend as much time choosing a tour group or guide as a restaurant. The important thing is to build back the kind of tourism that supports nature.”

Lisa W. Foderaro is a former reporter for The New York Times whose work has also appeared in National Geographic and Audubon Magazine.

Follow New York Times Travel on Instagram , Twitter and Facebook . And sign up for our weekly Travel Dispatch newsletter to receive expert tips on traveling smarter and inspiration for your next vacation.

Come Sail Away

Love them or hate them, cruises can provide a unique perspective on travel..

Cruise Ship Surprises: Here are five unexpected features on ships , some of which you hopefully won’t discover on your own.

Icon of the Seas: Our reporter joined thousands of passengers on the inaugural sailing of Royal Caribbean’s Icon of the Seas . The most surprising thing she found? Some actual peace and quiet .

Th ree-Year Cruise, Unraveled: The Life at Sea cruise was supposed to be the ultimate bucket-list experience : 382 port calls over 1,095 days. Here’s why those who signed up are seeking fraud charges instead.

TikTok’s Favorite New ‘Reality Show’: People on social media have turned the unwitting passengers of a nine-month world cruise into “cast members” overnight.

Dipping Their Toes: Younger generations of travelers are venturing onto ships for the first time . Many are saving money.

Cult Cruisers: These devoted cruise fanatics, most of them retirees, have one main goal: to almost never touch dry land .

What is overtourism and how can we overcome it?

The issue of overtourism has become a major concern due to the surge in travel following the pandemic. Image: Reuters/Manuel Silvestri (ITALY - Tags: ENTERTAINMENT)

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Joseph Martin Cheer

Marina novelli.

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Travel and Tourism is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, travel and tourism.

Listen to the article

- Overtourism has once again become a concern, particularly after the rebound of international travel post-pandemic.

- Communities in popular destinations worldwide have expressed concerns over excess tourism on their doorstep.

- Here we outline the complexities of overtourism and the possible measures that can be taken to address the problem.

The term ‘overtourism’ has re-emerged as tourism recovery has surged around the globe. But already in 2019, angst over excessive tourism growth was so high that the UN World Tourism Organization called for “such growth to be managed responsibly so as to best seize the opportunities tourism can generate for communities around the world”.

This was especially evident in cities like Barcelona, where anti-tourism sentiment built up in response to pent-up frustration about rapid and unyielding tourism growth. Similar local frustration emerged in other famous cities, including Amsterdam , Venice , London , Kyoto and Dubrovnik .

While the pandemic was expected to usher in a new normal where responsible and sustainable travel would emerge, this shift was evidently short-lived, as demand surged in 2022 and 2023 after travel restrictions eased.

Have you read?

Ten principles for sustainable destinations: charting a new path forward for travel and tourism.

This has been witnessed over the recent Northern Hemisphere summer season, during which popular destinations heaved under the pressure of pent-up post-pandemic demand , with grassroots communities articulating over-tourism concerns.

Concerns over excess tourism have not only been seen in popular cities but also on the islands of Hawaii and Greece , beaches in Spain , national parks in the United States and Africa , and places off the beaten track like Japan ’s less explored regions.

What is overtourism?

The term overtourism was employed by Freya Petersen in 2001, who lamented the excesses of tourism development and governance deficits in the city of Pompei. Her sentiments are increasingly familiar among tourists in other top tourism destinations more than 20 years later.

Overtourism is more than a journalistic device to arouse host community anxiety or demonize tourists through anti-tourism activism. It is also more than simply being a question of management – although poor or lax governance most definitely accentuates the problem.

Governments at all levels must be decisive and firm about policy responses that control the nature of tourist demand and not merely give in to profits that flow from tourist expenditure and investment.

Overtourism is often oversimplified as being a problem of too many tourists. While that may well be an underlying symptom of excess, it fails to acknowledge the myriad factors at play.

In its simplest iteration, overtourism results from tourist demand exceeding the carrying capacity of host communities in a destination. Too often, the tourism supply chain stimulates demand, giving little thought to the capacity of destinations and the ripple effects on the well-being of local communities.

Overtourism is arguably a social phenomenon too. In China and India, two of the most populated countries where space is a premium, crowded places are socially accepted and overtourism concerns are rarely articulated, if at all. This suggests that cultural expectations of personal space and expectations of exclusivity differ.

We also tend not to associate ‘overtourism’ with Africa . But uncontrolled growth in tourist numbers is unsustainable anywhere, whether in an ancient European city or the savannah of a sub-Saharan context.

Overtourism must also have cultural drivers that are intensified when tourists' culture is at odds with that of host communities – this might manifest as breaching of public norms, irritating habits, unacceptable behaviours , place-based displacement and inconsiderate occupation of space.

The issue also comes about when the economic drivers of tourism mean that those who stand to benefit from growth are instead those who pay the price of it, particularly where gentrification and capital accumulation driven from outside results in local resident displacement and marginalization.

Overcoming overtourism excesses

Radical policy measures that break the overtourism cycle are becoming more common. For example, Amsterdam has moved to ban cruise ships by closing the city’s cruise terminal.

Tourism degrowth has long been posited as a remedy to overtourism. While simply cutting back on tourist numbers seems like a logical response, whether the economic trade-offs of fewer tourists will be tolerated is another thing altogether.

The Spanish island of Lanzarote moved to desaturate the island by calling the industry to focus on quality tourism rather than quantity. This shift to quality, or higher yielding, tourists has been mirrored in many other destinations, like Bali , for example.

Dispersing tourists outside hotspots is commonly seen as a means of dealing with too much tourism. However, whether sufficient interest to go off the beaten track can be stimulated might be an immoveable constraint, or simply result in problem shifting .

Demarketing destinations has been applied with varying degrees of success. However, whether it can address the underlying factors in the long run is questioned, particularly as social media influencers and travel writers continue to give attention to touristic hotspots. In France, asking visitors to avoid Mont Saint-Michelle and instead recommending they go elsewhere is evidence of this.

Introducing entry fees and gates to over-tourist places like Venice is another deterrent. This assumes visitors won’t object to paying and that revenues generated are spent on finding solutions rather than getting lost in authorities’ consolidated revenue.

Advocacy and awareness campaigns against overtourism have also been prominent, but whether appeals to tourists asking them to curb irresponsible behaviours have had any impact remains questionable as incidents continue —for example, the Palau Pledge and New Zealand’s Tiaki Promise appeal for more responsible behaviours.

Curtailing the use of the word overtourism is also posited – in the interest of avoiding the rise of moral panics and the swell of anti-tourism social movements, but pretending the phenomenon does not exist, or dwelling on semantics won’t solve the problem .

Solutions to address overtourism

The solutions to dealing adequately with the effects of overtourism are likely to be many and varied and must be tailored to the unique, relevant destination .

The tourism supply chain must also bear its fair share of responsibility. While popular destinations are understandably an easier sell, redirecting tourism beyond popular honeypots like urban heritage sites or overcrowded beaches needs greater impetus to avoid shifting the problem elsewhere.

Local authorities must exercise policy measures that establish capacity limits, then ensure they are upheld, and if not, be held responsible for their inaction .

Meanwhile, tourists themselves should take responsibility for their behaviour and decisions while travelling, as this can make a big difference to the impact on local residents .

Those investing in tourism should support initiatives that elevate local priorities and needs, and not simply exercise a model of maximum extraction for shareholders in the supply chain.

How is the World Economic Forum supporting the development of cities and communities globally?

The Data for the City of Tomorrow report highlighted that in 2023, around 56% of the world is urbanized. Almost 65% of people use the internet. Soon, 75% of the world’s jobs will require digital skills.

The World Economic Forum’s Centre for Urban Transformation is at the forefront of advancing public-private collaboration in cities. It enables more resilient and future-ready communities and local economies through green initiatives and the ethical use of data.

Learn more about our impact:

- Net Zero Carbon Cities: Through this initiative, we are sharing more than 200 leading practices to promote sustainability and reducing emissions in urban settings and empower cities to take bold action towards achieving carbon neutrality .

- G20 Global Smart Cities Alliance: We are dedicated to establishing norms and policy standards for the safe and ethical use of data in smart cities , leading smart city governance initiatives in more than 36 cities around the world.

- Empowering Brazilian SMEs with IoT adoption : We are removing barriers to IoT adoption for small and medium-sized enterprises in Brazil – with participating companies seeing a 192% return on investment.

- IoT security: Our Council on the Connected World established IoT security requirements for consumer-facing devices . It engages over 100 organizations to safeguard consumers against cyber threats.

- Healthy Cities and Communities: Through partnerships in Jersey City and Austin, USA, as well as Mumbai, India, this initiative focuses on enhancing citizens' lives by promoting better nutritional choices, physical activity, and sanitation practices.

Want to know more about our centre’s impact or get involved? Contact us .

National tourist offices and destination management organizations must support development that is nuanced and in tune with the local backdrop rather than simply mimicking mass-produced products and experiences.

The way tourist experiences are developed and shaped must be transformed to move away from outright consumerist fantasies to responsible consumption .

The overtourism problem will be solved through a clear-headed, collaborative and case-specific assessment of the many drivers in action. Finally, ignoring historical precedents that have led to the current predicament of overtourism and pinning this on oversimplified prescriptions abandons any chance of more sustainable and equitable tourism futures .

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing