National Geographic content straight to your inbox—sign up for our popular newsletters here

- RACE IN AMERICA

Life after the ‘Green Book’: What is the future for Black travelers in America?

Today’s Black travel leaders inspire and build community. But much needs to change before travel is truly equal.

The Black travel market has grown substantially since the era of the Green Book. Pre-pandemic, African Americans collectively spent $63 billion a year on travel, according to one study.

I grew up knowing that Black folks travel. The dining room table at Akwaaba, my parents’ Brooklyn-based inn, hosted a steady rotation of Black travelers from around the U.S. and the world. Over warm biscuits and creamy grits, they talked about the museum exhibit they planned to see and the Broadway show that left them breathless.

While they loved those New York City staples, they always said the real highlight of their trip was the fellowship they shared at the inn . Staying in a Black home with like-minded guests made them feel safe, seen, and celebrated.

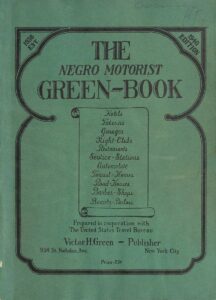

This equal access and freedom to travel was the aspirational goal of mail courier Victor Hugo Green, from Harlem, New York, when he founded The Negro Motorist Green Book . Known as “the bible” of Black travel, the guidebook was published from 1936 to 1967, listing the guest houses, restaurants, beauty parlors, night clubs, gas stations, and other places that were safe for Black travelers. Later in its evolution, the Green Book became the go-to resource for a newly emerging class of Black leisure travelers who wanted “a vacation without aggravation.”

Founded in 1936 by Harlem mail courier Victor Hugo Green, the Green Book listed safe places welcoming to Black motorists (pictured, the cover of the 1940 edition).

The 1957 edition of the Green Book reflects the evolution of the guide to appeal to a newly emerging class of Black leisure travelers who wanted “a vacation without aggravation.”

Green knew that their journeys were fraught with challenges—not only the indignity of being denied service at white-only establishments but, in the worst cases, the possibility of being jailed, assaulted, or even killed in “sundown towns,” which decreed non-whites leave town limits before nightfall. Fans of HBO’s horror-drama series Lovecraft Country saw this depicted in a tense scene in the premiere episode. The leading characters barrel through a field, trying to outrun sunset, knowing that what awaits them if they fail could be fatal.

( Related: Take a Green Book–inspired road trip along Alabama’s Civil Rights Trail .)

Nowadays, a diversity of sources, from boutique tour companies to family bloggers, provides the type of information the Green Book once did—and more. They not only support Black businesses but also build community within an African-American market that collectively spends, based on pre-pandemic research, $63 billion a year on travel .

But in an exhausting year of political crises and social change—which included both the killing of George Floyd and the mainstreaming of the Black Lives Matter movement , a polarizing election and the removal of Confederate monuments —the ideals to which Green aspired seem as elusive as ever. We asked Black travel leaders about the legacy of the historic guidebook and what Black travelers need now.

Next-generation Green Book

“One of the biggest compliments Nomadness Travel Tribe has ever gotten is that we are the New Age, internationally based, digital Green Book,” says Evita Robinson. “We are a safe space, and that’s what the Green Book was.”

Contemporary resources for Black travelers go beyond listing a friendly place for a meal; they find like-minded tribes and create networks. Robinson founded Nomadness in 2011 as a Facebook group of millennial travelers of color, mostly women. The community now hosts an annual summit for Black travelers, which drew more than 500 attendees at their virtual installment, Audacity Digi, in October.

Robinson knows it’s not just about finding a travel-compatible crew but also uplifting others in the community. In her journeys, Robinson seeks out Black businesses that her organization can support, including some storied establishments that first appeared in the Green Book’s pages, such as Clifton’s Cafeteria in Los Angeles and Green Acres Cafe in Birmingham.

Karen Akpan and her son, Aidan, explored Antigua, Guatemala, before the pandemic. Akpan is the founder of Black Kids Do Travel, an online community organized to share Black family travel experiences.

Martinique Lewis, author of ABC Travel Green Book , wants travelers to know that Black history can be found everywhere, often in unexpected places. “I went to Amsterdam in June 2018, and, as ignorant as it sounds, I had no idea that Amsterdam had all of this rich Black history,” Lewis says. “I took Jennifer Tosch’s Black Amsterdam tour, and I was both blown away and upset at what I saw. In the Red Light District, for example, a place where every traveler to Amsterdam goes, all you have to do is look up, and you’ll see Black faces carved into statues from the 1600s. I was thinking, ‘why isn’t this the tour that’s being promoted?’”

( Related: Here’s how travelers of color are smashing stereotypes .)

Highlighting lesser known tours, businesses, and events, Lewis’s guidebook honors and illuminates the African diaspora globally and celebrates Black communities from Ecuador to South Korea.

“It’s such a great feeling when I go to a place where I didn’t expect to see Black people,” Lewis says. “When I do, I just want to cling to them; I want to know their stories.”

Zim Flores, founder of the boutique travel and media company Travel Noire helps people create their own adventurous travel stories. When Travel Noire first emerged on Instagram in 2013, Black folks flocked to the page to witness themselves taking up space around the world. It was, and still is, a vision board. With more than 600,000 followers on Instagram, Travel Noire now offers itineraries for destinations across the globe, from Morocco to Malta.

“Black people travel for so many different reasons. Some of us want to visit Black historical landmarks, some of us want to go someplace totally foreign from us and what we know,” Flores says.

She wants to encourage Black travelers to voyage fearlessly. “I’m in the business of shaking up mindsets, but it would be naive of me to tell people, ‘Just go! Don’t worry.’ I’ve always thought to myself, there are multiple experiences that someone can have at any given time, in any given country. Let me go and find out for myself,” Flores says. “I think that was what worked so well for Travel Noire. I was a bold and courageous traveler, and I was willing to go anywhere. And because I went, it allowed other Black travelers to see that they could do it, too.”

( Related: Discover what this writer learned as a Black solo traveler .)

Parker McMullen Bushman and Crystal Egli founded Yelp-like website Inclusive Journeys to broaden the Green Book’s audience. “We thought, ‘What if there was a crowdsourced database of safe spaces like the original Green Book, but with a twist?’” says Bushman. “We want to include all different types of marginalized identities and create a listing of businesses with physical amenities that speak to their needs. For example, does a restaurant have gender-neutral bathrooms for trans guests? Is it wheelchair accessible?”

Related: photos from the African American History Museum

Another goal of Inclusive Journeys was to gather the data and resources to make an economic case for inclusivity. Companies “don’t want to make a change because it’s the right thing to do; they want a financial incentive,” says Bushman. “Economics and data are the two things that can really change policy and practices at a higher level,” says Egli.

But its website is not just about the data. “We also want to be more subjective with our inclusivity rating,” says Bushman. “We want to ask people: Did you feel safe in this space? Did you feel welcomed? Did you feel celebrated, not just tolerated? As a Black woman, I never know how someone’s conscious or unconscious biases will manifest when they serve me. If other people can vouch for an establishment, suddenly you can live life without that worry on your shoulders.”

Do we need a new Green Book?

In the 1948 annual edition of his book, editor Green wrote, “There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States.”

Part of the Green Book’s triumph—and eventual obsolescence—lies in the fact that laws did change: Black people can now legally go anywhere. When Candacy Taylor first started research on her book Overground Railroad: The Green Book and the Roots of Black Travel in America , people would tell her they were shocked the Green Book ever existed. “They said, ‘Thank God we don’t need that anymore!’” says Taylor.

With Jim Crow laws in effect in 1940, waiting rooms at a Durham, North Carolina, bus station were racially segregated.

“Then Trump got elected in 2016, and so much started happening politically that people began saying, ‘We need a new Green Book! We need a new Green Book!’” Taylor continues. “But I believe what they’re really longing for is a sense of freedom and empowerment through travel.” That freedom continues to be threatened.

“While the Green Book provided an index of places Blacks could receive service, that didn’t mean you’d get there alive—there were still sundown towns and racist cops—and that was the bigger issue,” says Taylor.

( Related: For Black motorists, there is a never-ending fear of being stopped .)

On the heels of a historic election—one that continued to highlight the national divide the country didn’t mend after the Civil War, nor when Jim Crow ended—Taylor says there is much work to be done before Black travelers are relieved of the creeping discomfort that occurs when traveling to a new or potentially unwelcoming place.

“A new Green Book isn’t going to solve that problem,” says Taylor. “Those who say we need a new Green Book are seeking a freedom that won’t truly be felt until we get to the root of systematic racism in this country.”

Taylor’s sentiments are a precautionary reminder to those who optimistically hold on to a belief that so much has changed. Still, Black travelers—Robinson, Lewis, Flores, Bushman, Egli, and the like—continue to answer the call of the road. We journey on, just as the Black travelers before us did, who held the Green Book close in search of safety and new horizons. We can’t say no. For all of us, travel is freedom.

Related Topics

- CULTURAL TOURISM

- AFRICAN AMERICANS

You May Also Like

Before the Great Migration, there was the Great Exodus. Here's what happened.

How Black travelers are reclaiming Portugal

Become a subscriber and support our award-winning editorial features, videos, photography, and much more..

For as little as $2/mo.

These African American history museums amplify the voices too often left unheard

Why February is Black History Month

Charleston’s newest museum reckons with the city’s role in the slave trade

Americans have hated tipping almost as long as they’ve practiced it

Who were the original 49ers? The true story of the California Gold Rush

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Adventures Everywhere

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Why These Professors Helped Create a ‘History Of Black Travel’ Timeline

Black history is often told through the lens of enslavement and segregation, focusing on centuries of struggle as opposed to centering the progress and positive strides Black people continue to make in the face of adversity. Unfortunately, travel history is no different: Textbooks and heritage sites often omit Black historical narratives and travel pioneers, instead highlighting traditionally romanticized and comfortable versions of predominantly white, male, Eurocentric history .

Following another round of publicized brutality of Black people during the summer of 2020, Black travel leaders shared loudly that a spotlight on systemic racism within the tourism industry was long overdue . This global reckoning with race led to big questions, like why the travel industry needs to address its own (lack of) diversity and how the history of Black travel has historically been left out of the conversation. Almost two years later, the recent pushback against anti-racist teaching in U.S. public schools has many educators and parents concerned with how government-mandated censorship continues to whitewash and romanticize American history lesson plans. These concerns are echoed within the tourism industry with tourist sites, destinations, and museums questioning their role in how the telling of marginalized narratives , specifically Black history, should be represented.

Recognizing these stark inequities, the Black Travel Alliance , a non-profit created to encourage, educate, and equip Black travel professionals , teamed up with the organization we co-direct, Tourism RESET , an interdisciplinary research and outreach initiative that seeks to identify, study, and challenge patterns of social inequity in the tourism industry. We collectively decided that we could no longer wait for Black travel history to be readily available and accessible to the public. As educators committed to social equity and inclusion, we believe now is the time to teach the public about how the African Diaspora traveled to every inch of the earth and how they progressively made—and are making—their mark on the travel industry, from centuries past to the present day.

Thus, the ‘ History Of Black Travel’ timeline was born.

The project has required almost two years worth of volunteered hours to research, source, and categorize over 130 entries from the Americas, focusing mainly on the United States. The content of the timeline spans twelve main categories: Ally, Accommodations, Explorers, Government, Groundbreakers, Leisure, Migration, Organizations, Publishing, Slavery, Television, and Transportation, all with the aim of highlighting Black travel pioneers along with major migration routes and leisure travel developments.

The name Kellee Edwards, the very first Black woman to host a show on the Travel Channel may ring a bell, but did you know about Barbara Hillary , the first known Black woman and oldest person to reach the North and South Poles? How about the Highland Beach Resort , which was started by the son of abolitionist Frederick Douglass, Charles Douglass, who bought land in Highland after another Maryland resort denied him entry, thus creating a mecca for Black tourists during the late 1800s? Or the Henderson Travel Agency? Preceding today’s wave of Black travel leaders, in 1955, Freddye Henderson and her husband, Jacob, opened Henderson Travel Service in Atlanta to assist African-Americans who wanted to travel internationally, thus paving the way for what we now know as an international movement of Black travelers . The timeline also includes major judicial, legislative, cultural, and historical events that have inspired Black travel as a mechanism for freedom. This is not exclusive to the U.S., and as such, our plan is to continue expanding the timeline to add Black travel stories from all continents across the globe.

As academics and industry practitioners, we are adamant about stressing the importance of the tourism industry taking a clear stand. A stand to amplify Black stories with the assistance of the timeline, even as intense pushback against the accurate telling of American history continues, be it through censorship , burning of books , and laws that perpetuate silence around discussing race globally.

But the History Of Black Travel timeline is not just for industry stakeholders. It’s for travelers of any racial or ethnic background. Our hope is that the timeline is used both as a tool for education and a resource to start meaningful conversations among travelers as they make decisions about destinations to visit, companies to support, and activities to partake in. We want it to inspire tours and destination websites that highlight Black history, the creation of Black heritage travel festivals, compensation for collaborations with Black content creators to amplify Black history within communities, and more.

Travel is meant to be transformative, and it is up to us to be the catalyst of the change we want to see towards more diversity and inclusion across the industry—one Black history timeline entry at a time.

Stefanie Benjamin is Assistant Professor in the Department of Retail, Hospitality, and Tourism Management at the University of Tennessee. Alana Dillette is an Assistant Professor of Hospitality and Tourism Management at San Diego State University. They are both Co-Directors of Tourism RESET, a multi-university and interdisciplinary research and outreach initiative that seeks to identify, study, and challenge patterns of social inequity in the tourism industry.

By signing up you agree to our User Agreement (including the class action waiver and arbitration provisions ), our Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement and to receive marketing and account-related emails from Traveller. You can unsubscribe at any time. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Plan Your Visit

- Group Visits

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Accessibility Options

- Sweet Home Café

- Museum Store

- Museum Maps

- Our Mobile App

- Search the Collection

- Initiatives

- Museum Centers

- Publications

- Digital Resource Guide

- The Searchable Museum

- Exhibitions

- Freedmen's Bureau Search Portal

- Early Childhood

- Talking About Race

- Digital Learning

- Strategic Partnerships

- Ways to Give

- Internships & Fellowships

- Today at the Museum

- Upcoming Events

- Ongoing Tours & Activities

- Past Events

- Host an Event at NMAAHC

- About the Museum

- The Building

- Meet Our Curators

- Founding Donors

- Corporate Leadership Councils

- NMAAHC Annual Reports

Traveling Through Jim Crow America

During the segregation era, discriminatory laws and practices made traveling by car a problematic and even dangerous experience for African Americans. Along the nation’s highways, black travelers were routinely denied access to essential services like gas, food, restrooms, and lodging. Stopping in an unfamiliar place carried the risk of humiliation, threats, or worse. To find safe and friendly accommodations, travelers relied on a network of shared advice, exchanged by word of mouth and also published in travel guides such as the "Green Book."

The Negro Motorist Green Book, Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

The Negro Motorist Green Book was a guidebook for African American travelers. #APeoplesJourney

"The Negro Motorist Green Book," pictured above from our collection, was a guidebook for African American travelers that provided a list of hotels, boarding houses, taverns, restaurants, service stations, and other establishments throughout the country that served African American patrons. The information included in the Green Book helped increase their safety and treatment. During the Jim Crow era, laws enforced segregation in the South between 1877, the post-Reconstruction era, and up through the 1950s at the beginning of the civil rights movement. The term "Jim Crow" came from a minstrel show character and marks almost a century of legal segregation and discrimination against African Americans.

The Negro Motorist Green Book was a guidebook for African American travelers that provided a list of hotels, boarding houses, taverns, restaurants, service stations and other establishments throughout the country that served African Americans patrons.

Published from 1936 to 1966, the Negro Motorist Green Book listed motels, restaurants, service stations, and other accommodations that served African Americans. Victor H. Green, a New Jersey Postal Worker, created his namesake guide to help black travelers safely navigate the segregated realities of Jim Crow America. Green used his contacts in the postal service, as well as input from traveling salespeople and business owners, to complete the listings. He also partnered with the Standard Oil Company to distribute The Green Book at Esso gas stations.

Travel back in time and take a cross-country trip with help from the Green Book on our second floor Explore More! interactive!

Subtitle here for the credits modal.

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- The Lit Hub Podcast

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

From Jim Crow to Now: On the Realities of Traveling While Black

Mia bay maps the history of segregated travel.

In 1922 Joseph K. Bowler told a reporter for the Chicago Defender that he never ventured to the South without a “Jim Crow traveling kit.” Designed to allow Bowler, a minister who lived in Massachusetts, to travel through segregated states in relative comfort, the kit included “a pair of soiled overalls purchased from an auto mechanic, a miniature gasoline stove and a small table top the size of a scrub board.” The contents of Bowler’s kit vividly illustrate some of the indignities and discomforts that Black travelers could expect to encounter in the “colored” railroad cars of his era. He wore the overalls, he explained, to avoid the expense of “soiling” good clothes in the “dirty Jim Crow coaches.”

They protected him from the tobacco juice that white conductors and news vendors often spat on the seats, and were especially useful in “parts of the Mississippi [where] the white farmers use the Jim Crow coaches as luggage cars in which to transport chickens and hogs.” The stove and table top allowed him to prepare and eat meals. They were key components of his kit, given that “the dining car is a closed corporation as far as our people are concerned.” “White people below the Mason Dixon line maintain that we are animals, virtually camels, and can go without food or water for several days,” noted the intrepid traveler, who both carried and cooked all the food he consumed on his journey. If he had not, he explained, he would have had to “sneak into the back of some depot like a little poodle and ask for some food,” or “risk being shot to death by invading a dining car to secure my meals.”

Many Black travelers shared Bowler’s concerns—whether or not they chose to wear dirty overalls and carry stoves. African Americans loathed segregated streetcars and railway compartments more than virtually any other form of segregation. In the research for his detailed account of race relations in the American South, Following the Color Line: An Account of Negro Citizenship in the American Democracy (1908), journalist Ray Stannard Baker found that “no other point of contact is so much and so bitterly discussed among Negroes as the Jim Crow car.” A third of a century later, Swedish sociologist Gunnar Myrdal, in his monumental study The American Dilemma (1944), made the same point: “It is a common observation that the Jim Crow Car is resented more bitterly among Negroes than most other forms of segregation.”

By the 1940s African Americans did not have to travel by train. They had new options to choose from, but they found all of them problematic. The intercity bus lines that first began operating in the late 1920s offered an afford able alternative to traveling by rail, but during their early years of operation many bus companies refused to serve Black passengers. Even after the courts forced them to, they did so “only grudgingly and in the most uncomfortable seats.” “If you think riding a Jim Crow car out of the South is no fun,” wrote one Black traveler in 1943, “you should try bumping along on the back wheel of a bus, with the odors of the motor keeping you restless.”

Cars initially seemed to offer those who could afford them an escape from the humiliations of Jim Crow travel. But while Black motorists could choose their own seats in their own cars, they could not expect to be treated with respect once they stepped outside their vehicles. “It used to be that black people only took a trip [if] some body died or was dying,” remembered Chicago Tribune columnist Jeannye Thornton in 1972. Driving usually involved a “nonstop trip,” because hotels and motels that accepted Black guests were almost impossible to find. Even rest stops were hard to locate: “Bathrooms were always at the next service in the next town 50 miles down the road and when you finally got there, they were always separate and filthy.” African American travelers ended up driving “all night [and] sometimes traveling to a big city before even considering stopping to stretch.” Not only were road side accommodations unappealing, driving through the South could be dangerous. “Who knows what could happen to a black family with northern license plates traveling some lonely road?”

Even travel by air was far from free of discrimination. Flying itself was never subject to southern segregation laws, but in the early days of air travel some airlines refused to carry Black passengers, and others assigned them to segregated seats. And when they escaped segregation in the air, Black flyers often encountered it on the ground. Southern airports had segregated waiting rooms, restaurants, and restrooms, and the taxis and ground transportation services that carried passengers to and from airports were divided by race.

American identity has long been defined by mobility and the freedom of the open road, but African Americans have never fully shared in that freedom. Travel segregation began on the stagecoaches and steamships of the North east—the nation’s earliest common carriers—and moved from there to rail roads, train stations, restaurants, roadside rest stops, and gas station rest rooms, all of which were eventually segregated by law in the South. As new modes of transportation and accommodations developed, new forms of segregation followed.

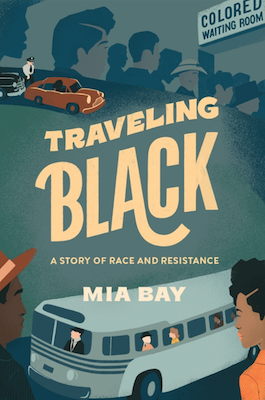

In Traveling Black, I explore the intertwined history of travel segregation and Black struggles for freedom of movement in America from the antebellum era to the present day. The chapters are organized around the successive forms of long-distance transportation adopted by Americans, and they follow the experiences of generations of African American travelers as they encountered and resisted segregation and discrimination on stagecoaches, steamships, and railways, and in cars, buses, and planes. They document a sustained fight for mobility that falls largely outside the organizational history of the civil rights movement. The final chapters highlight the successes of that fight—recording the struggles that led to the overthrow of Jim Crow transportation—and close with a discussion of inequities in modern transportation. In studying how segregated transportation worked, and how and why its eradication became so central to the African American freedom struggle, this book examines Black mobility as an enduring focal point of struggles over equality and difference.

The history of travel is a critical but often overlooked aspect of the Black experience in America. Historians, like anthropologists, tend to study their subjects in ways that privilege “relations of dwelling over relations of travel”— to borrow James Clifford’s phrase. This may be particularly true in the field of African American history, where we often study the members of a group with an almost unparalleled record of displacement and migration as “Black southerners” or “Black northerners” or residents of specific communities.

Although such approaches are vital to understanding Black people’s deep roots in particular places, they do not always capture the significance of movement in African American life. Repeatedly displaced during slavery, Black southerners kept moving long after emancipation, in a series of migrations that took them from their regions’ plantations and farms to its cities and towns, and beyond. The Great Migration of more than six million southern Blacks to the North and West between 1916 and 1970 only accelerated this process, adding a new chapter to what Ira Berlin has called Black America’s “contrapuntal narrative” of “movement and place.”

Within this narrative, few African Americans ever escaped travel restrictions entirely. We associate Jim Crow cars and buses with the South, but travel segregation was never neatly confined to one region of the country. An artifact of emancipation, it took shape alongside the abolition of slavery, arriving first in the northern states that abolished slavery in the wake of the American Revolution. These densely populated states were home to many of the nation’s earliest common carriers, most of which went into business at a time when white northerners were reluctant to interact with their formerly enslaved Black counterparts on equal terms, especially within the close confines of stagecoaches, steamboats, and railway cars. Antebellum-era white northerners often insisted that African Americans ride on the roofs of stagecoaches, on the outside decks of steamboats, and in the railroads’ dirtiest and most dangerous coaches—which came to be known as Jim Crow cars.

These segregated spaces were never as entrenched in the North as they later became in the South, where Jim Crow cars began to be mandated by law starting in the 1880s. Indeed, that same decade saw some northern states pass legislation designed to protect Black civil rights. But racial discrimination in transportation followed Black travelers up and down the railroad lines that took so many of them out of the Mississippi Delta, the Virginia Piedmont, and other regions across the South during the Great Migration.

Some of the segregation that followed African Americans north was closely linked to the South’s Jim Crow system. Prior to the 1950s, many conductors on southbound trains began herding Blacks into the Jim Crow car as far north as Chicago and New York and as far west as Los Angeles. “A Negro car is set aside for the convenience of passengers traveling south of Washington, so they will not have to change,” explained agents for the Pennsylvania Railroad, which routinely assigned all of its southbound Black passengers to this car until 1949. That year a lawsuit brought by ministers who were assigned to the Jim Crow car in Chicago finally forced the Pennsylvania Railroad to abandon this practice.

But in California the Jim Crow seating of Dixie-bound Black passengers persisted even after that. As late as the mid-1950s, African Americans who secured tickets on the Southern Pacific’s streamliner from Los Angeles to New Orleans would find themselves “all together in car 22 . . . at the front of the train just behind the engine.” Such forms of segregation were even more ubiquitous in border cities such as Cincinnati and Washington, D.C., which were for many years what one journalist termed “Big Change Terminals.” Gateways to the South, these were stations where railway officials forced all southbound Black passengers who were not already seated at the front of the train to, as one reporter put it, “dutifully tote their shoe boxes filled with fried chicken, pigs feet, cake and cornbread, blankets and squealing kids into the Jim Crow Car.” African Americans who traveled by bus like wise had to move to the back of the bus in Washington, D.C., and other border cities—although some bus lines, like the railroad lines, seated Blacks in the back as far north as Chicago and New York, “to ‘save Negroes the embarrassment’ of having to change to a rear seat in Washington.”

White northerners also practiced forms of travel segregation and exclusion that were in no way dictated by southern customs. White-only hotels and rooming houses were common in virtually every region of the country right up until the 1960s, when they were finally outlawed by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the US Supreme Court case Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States (1964). “It is understood that the southern states from Maryland to Texas are the colored vacationist’s NoMan’sLand, but it is not so generally understood (except by Negroes) that the same thing is true of the rest of the country,” explained the African American writer George Schuyler to his white readers in 1943.

This point had been driven home to Schuyler in the spring of 1943, when he and his wife had sent out a letter seeking vacation accommodations for a “colored family of three” to 105 northeastern vacation spots, all of which placed regular advertisements for guests in the Sunday section of a greater metropolitan newspaper. They received only one positive response. The Anchor Inn in the Poconos was happy to accommodate the Schuyler family. Seventy-four of the businesses did not even bother to reply to the inquiry; most of the others claimed to be “sold out” or “booked to capacity, from now until Labor Day.” The few that were willing to explain why they could not accommodate the Schuylers clearly spoke for the rest. “We have never had colored guests at the Oakledge Manor,” a Vermont hotelier explained, “and fear that our other guests might make you feel ‘left out’ of our activities and entertainments.”

Finding food on the road was likewise a national problem. While more welcoming than hotels, northern restaurants practiced overt and covert forms of segregation and exclusion that varied from place to place. In Ohio, which passed a civil rights law banning discrimination in public accommodations in 1884 but never enforced it, some restaurant owners served only whites and even placed signs advertising that fact in their windows. In New York, which had stronger anti-discrimination laws, Black customers were rarely refused service, but their patronage was discouraged in other ways. Often seated only after a lengthy wait, Black diners were routinely ushered to tables in “undesirable locations . . . near kitchens, bathrooms, swinging doors” and other out-of-the-way spots and were subject to rude service. Such practices were common enough to make the writer and frequent traveler Langston Hughes wonder “where and how America expects Negro travelers to eat.” Having been, by a “conservative estimate,” refused service in restaurants in at least a hundred cities, he had no answer. “Many communities have no Negro operated restaurants. And even where there are colored restaurants, how is a complete stranger supposed to know where the Negro places are located? Colored travelers do not usually have time to walk all over town looking for a place to eat.”

Hughes’s lament highlights one of the defining difficulties of traveling Black, which was simply that Black travelers could never be sure where they were welcome. Localized rather than uniform, and far from obvious, the nation’s patchwork of segregationist laws and practices took shape unevenly over time. As C. D. Halliburton pointed out in the Philadelphia Tribune, they varied so much that they inevitably put any Black person “in unfamiliar surroundings in the most uncomfortable state of uncertainty, embarrassment and insecurity.” This problem was most acute in the North and West, where there were no segregation signs and few Black restaurants or hotels. Blacks had little choice but to try white establishments, but, as Black editor P. L. Prattis complained, “you could never know where insult and embarrassment are waiting for you.”

Segregationist practices were inconsistent even in the South. Jim Crow laws were largely similar across the region, and “white” and “colored” signs divided many facilities by race. But there, as Prattis noted, Black travelers navigated a landscape made mystifying by any number of “contrary and confusing customs.” Although accustomed to segregation, Albon Lewis Holsey, an Atlanta native and Tuskegee Institute staffer, described a 1925 trip spent “Zig-Zagging through Dixie” as a “veritable night mare.” Not only did he encounter “the general discomforts of racial discriminations,” he was con founded by how frequently they varied from place to place.

On arriving in Memphis, Tennessee, where he had to transfer from one railroad station to another, he found that the city’s redcap porters and Yellow Cab drivers did not serve Black travelers. But when he reached Little Rock, Arkansas, just four hours away, he had no such difficulties: a redcap grabbed his bags and “whistled for a Yellow Cab.” In Tulsa he once again secured a cab, but only after some covert arrangements. The “white Taxi cabs” that served the station, he was told, “won’t haul colored passengers in the day, but at night, when no one is looking they will.” Lucky enough to have arrived in the evening, he could get a ride, but he would have to meet his driver “in the shadows behind the station.” Holsey’s attempt to book a Pullman sleeping car for an interstate trip out of Dallas presented other, more alarming, complications. “The railroads,” an agent for one of the trunk lines informed him, “are willing to sell the space to any passenger who is able to pay for it, but it is dangerous for colored people to ride in Pullman cars in Texas. In the first place, the Texas Law has never been interpreted to mean that the [Pullman] Drawing Room is a separate accommodation”—so traveling in one might be illegal—“and in the next place, you can never tell what may happen.”

A complex pastiche of law and custom created racial rules that were too inconsistent to be easily followed—or endured. Tennessee-born journalist Carl Rowan, who resettled in Minnesota after serving in the navy during World War II, revisited the land of his youth in 1951 only to be immediately reminded that to be Black in the South was to face “a life of doubt, of uncertainty as to what the reception will be, even from one building to another.” Some airports had segregated waiting rooms and restrooms; some did not. He had no trouble renting a car, but he was plagued by “doubt as to which filling station would allow me to buy gasoline and also to use the toilet. Doubt as to which restaurant would sell me food, even to take out.” Indeed, Rowan even wavered on whether he should keep the car he rented, and eventually decided to return it and travel by train and bus. “I did not know whether I would be stopped by policemen if I drove about town in the car,” he ex plained. “I knew that small-town policemen often become suspicious of a strange Negro in a new car.”

The doubts faced by Black travelers were not just about protocol. They were also about safety. As Rowan’s experience reminds us, traveling Black could involve greater dangers than simply being refused service. African American drivers have always attracted undue attention from the police, so traffic stops were one great fear. But travel of all kinds held danger. In the South especially, African Americans who breached segregation’s codes, knowingly or unknowingly, could be subject to violence. As some of the travel experiences featured in this book will show, taking the wrong seat got many travelers beaten, and some killed.

Unpredictable and dangerous, travel discrimination was a nightmare because it was virtually impossible to avoid—especially in the South. Black southerners could and did shield themselves from some of segregation’s slights by keeping to themselves. Indeed, the accommodationist philosophy promoted by Booker T. Washington, one of the region’s most famous African American leaders, encouraged Blacks to accept Jim Crow and seek economic empowerment by creating and patronizing Black businesses—some of which catered to Black travelers. However, even Washington conceded that this approach had its limitations. African American travelers could sometimes find Black hotels, livery services, and other travel amenities, but such businesses were not universally available, and few major common carriers were Black-owned. “We have no railroad cars and no steamboats, and we have to use yours,” explained the Black lawyer and politician George Henry White to his former colleagues at a congressional hearing in 1902, in the course of an unsuccessful attempt to secure congressional legislation outlawing segregation on American railroads.

Although privileged in other ways, elite Blacks were often even more familiar with travel discrimination than their poorer counterparts. Affluent enough to be early adopters of new travel technology, they began riding rail roads, buses, and planes, and buying cars well before the Black masses could easily afford to do so, and were sometimes all the more unwelcome as a result. The use of prestigious modes of transportation by affluent African Americans could be galling to whites, who resented sharing all but the rudest public accommodations with Blacks on equal terms. “White people have a dis tinct aversion to ‘associating’ with black people or meeting them in any relation that implies a social equality, even in public conveyances or places,” an editorialist for the New York Times explained in 1894. “It is not that white people object to the presence of negroes. They only insist that negroes shall be kept in their place. A negress in an unoccupied passenger [seat] on a parlor car would be looked sourly on by her white fellow passengers, even if they did not enter protests against her presence, whereas the same negress visibly employed as the nurse of white children, would be innocuous and welcome.” One southern politician made the same point more bluntly in explaining his support for the passage of separate cars laws. The target of such laws, he maintained, was not “good old farm hands and respectable Negroes,” but rather “that insolent class of Negroes who desired to force themselves into first class coaches.”

In the end, no class of Negroes could fully escape traveling Black: it was a formative part of life for wealthy Blacks, poor Blacks, and everyone in between. Race leaders such as Booker T. Washington, Mary Church Terrell, Ida B. Wells, W. E. B. Du Bois, Pauli Murray, Thurgood Marshall, Bayard Rustin, and Martin Luther King Jr. all traveled many miles to speak to a national audience. Other inveterate travelers whose journeys crisscross this book include Jack Johnson, a boxer who was an early car connoisseur; Jackie Robinson and countless other Black baseball players who preceded him in the Negro leagues; and musicians such as Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, and the blues singer Leadbelly, whose “Jim Crow Blues” featured the chorus “you gonna find some Jim Crow, everyplace you go.” This book includes many of their travel stories.

But Traveling Black also tracks the quotidian experiences of ordinary Black travelers. Among them were vacationers who, like the Schuyler family, simply sought a place to get away. As W. E. B. Du Bois noted in 1917, “ever recurring race-discrimination” discouraged easy getaways, especially among Af rican Americans of modest means. Unlike Du Bois, who could afford to travel from his home in New York to elite Black vacation spots such as Idlewild in Michigan, they often had to “stay near home.” However, even those who ventured farther could not escape Jim Crow humiliations. Ron Reaves, who grew up in Oklahoma in the 1950s, is a case in point. His father was a janitor who worked three jobs in order to be able to afford a car, which he used to take his family to the beaches of California or to Chicago in the summer. They had no brushes with discrimination at hotels or restaurants as they drove west because both were luxuries that they could not afford. Instead, they drove nonstop for twelve hundred miles. But the segregated landscape through which they traveled still made a lasting impression on Reaves, who remembered seeing “plenty of ‘no colored’ signs at Phillips gas stations and the like” and experiencing the sting of discrimination still more directly at some of the service stations where the family was able to stop. Although permitted to buy gas, they “had to pee out back and drink water from a dirty dingy ladle that was set up next to nice porcelain water fountains.”

__________________________________

Excerpted from Traveling Black by Mia Bay, published by Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2021 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Previous Article

Next article.

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

Black Travel Alliance Launches History Of Black Travel Website In Partnership With Tourism RESET

PRESS RELEASE For immediate release Tuesday, July 13, 2021

Black Travel Alliance Launches History Of Black Travel Website To Showcase The Development Of Black Leisure Travel In Partnership With Tourism RESET

Oakland, California (July 13, 2021) — Black Travel Alliance launched today a new website History Of Black Travel ( www.historyofblacktravel.com ) in partnership with Tourism RESET. Their vision is to work toward educating the public on how the African Diaspora traveled to every inch of the Earth, progressively making their mark within the travel industry, from centuries past into the present day.

“We are excited to partner with Tourism RESET on this groundbreaking project” states Ursula Petula Barzey, Research Committee Chair, Black Travel Alliance. “We brainstormed a number of research initiatives related to Black travel and in the end felt that the History Of Black Travel website with a timeline would have the most impact as it helps to educate and correct the misperception that Black people just started to travel for leisure. We have been traveling since the beginning of time and have made major contributions to the development of leisure travel and tourism.”

Included in the initial launch of the History Of Black Travel are 130+ timeline entries from the Americas, focusing mostly on the United States. The plan is to continue expanding the timeline to add Black leisure travel stories from all continents and countries across the globe. However, the Black Travel Alliance, along with Tourism RESET, are hoping for a co-construction approach, inviting suggestions from the wider community of travelers, historians, scholars, and tourism stakeholders who are interested in Black leisure travel.

This feedback will assist with the development of the twelve main categories of the timeline that will help viewers focus on different aspects of Black travel throughout various eras, locations, and decades. Major categories include accommodations, explorers, groundbreakers, and leisure travel developments spotlighting cultural sites and tours, festivals and major events, outdoor activities, food and drink, retail, and wellness.

The History Of Black Travel also has categories and entries related to slavery, migration, and the government with legislative and judicial rulings as they provide background and context for many of the Black leisure travel developments.

For destinations and travel brands who wish to tap into the Black leisure market, which according to a study from MMGY Global is valued at US$129.6 billion in the United States alone, the History Of Black Travel can be used as a resource to educate and guide discussions related to the contributions of Black people to travel historically, presently, and for the future. The History Of Black Travel can also serve as a valuable tool for educators looking to bring a different perspective from traditional media related to travel, tourism, and exploration.

“History not only tells us the story of our past but also informs our perspective as we move into the future. The History Of Black Travel timeline is a long-overdue tool for educators, researchers, and industry professionals to use in an effort to break down stereotypes and misconceptions of who the trailblazers in the travel industry really were states Dr. Alana Dillette, Co-Director, Tourism RESET. “ So often, Black people are plagued by the collective memory of slavery and the many injustices that followed. The History Of Black Travel timeline is an opportunity to shape-shift the narrative of Black travel history and own our stories – both the triumphs and the hardships.”

The launch team for the History Of Black Travel includes seven members of the Black Travel Alliance Co-Founders and Research Committee Members. Specifically:

- Ursula Petula Barzey , Founder & Digital Content Creator, CaribbeanAndCo.com

- Gabby Beckford , Gen Z Travel Expert at Packslight.com

- Donna-Kay Delahaye , Travel Blogger, Photographer, Digital Content Creator at HuesOfDelahaye.com

- Patricia King , Content Creator at SavvyTraveling.com

- Martinique Lewis , Diversity in Travel Consultant, Martysandiego.com

- Kerwin Mckenzie , Author, Content Creator, Speaker at Passrider.com

- Davida Wulff-Vanderpuije , Content Creator & Audio Storyteller at WondersOfWanders.com

Also, two Co-Directors from Tourism RESET:

- Stefanie Benjamin Ph.D. , Assistant Professor of Retail, Hospitality, and Tourism Management, University of Tennessee, Knoxville

- Alana Dillette Ph.D. , Assistant Professor, L. Robert Payne School of Hospitality and Tourism Management, San Diego State University

Notes to the Editor:

The correct name for the website is History Of Black Travel – so the first letter of each word in the title is capitalized.

Additional quotes from members of the History Of Black Travel project team covering a range of angles are below:

Angle: Ally perspective Stefanie Benjamin Ph.D Assistant Professor of Retail, Hospitality, and Tourism Management, University of Tennessee, Knoxville & Co-Director of Tourism RESET As someone who evolved from an ally to a co-conspirator, I’m challenging the system in which I benefit from. Amplifying the voices that are already doing this work, I’ve partnered with the Black Travel Alliance where we are working together to fight for social and racial justice. Some of this work is with the creation of the History Of Black Travel timeline which will serve as a pedagogical tool for educators – both K-12 and higher education. By unlearning and re-learning through a decolonized curriculum, this timeline will help with the disruption of dominant cultures’ lenses of history. Hopefully, this knowledge will contribute to creating an equitable present and future for all marginalized populations.

Angle: Gen Z perspective Gabby Beckford, Gen Z Travel Expert at Packslight.com Board Member, Research Committee Vice-Chair, Black Travel Alliance The History Of Black Travel timeline is essential for the youngest generation, and the generations to come. We need to know the context of how we got where we are. Knowing our history also helps us foster an appreciation for travel as a whole, as it’s never been more accessible than now, and we still have a lot of room for advancement in terms of equity, ownership, and representation in this market. And we need to know where we’re coming from to know where we want to go.

Angle: Black Solo Female/solo traveler perspective Donna-Kay Delahaye , Travel Blogger, Photographer, Digital Content Creator at HuesOfDelahaye.com Board Member & Research Committee Member, Black Travel Alliance The History Of Black Travel timeline is crucial as it shows that black women have been traveling solo for decades and making history while doing it. Especially in a time where it was not safe for Blacks to be traveling, much less a Black woman traveling by herself. The courage it must have taken for these Black female travelers inspires me daily and helps fuel’s my adventures and that of other solo Black female travelers who have followed in their footsteps. It teaches us that we can go where the adventure leads without fear.

Angle: Aviation perspective Kerwin Mckenzie, Author, Content Creator, Speaker at Passrider.com Board Member & Research Committee Member, Black Travel Alliance It’s pretty scary that Black aviators went through so many issues just to be able to learn to fly. And sadly, we still have issues. The History Of Black Travel timeline showcases the plight of Black aviators and how they have blazed the trail for us. The work continues.

Angle: Boomer perspective Patricia King , Content Creator at SavvyTraveling.com Board Member & Research Committee Member, Black Travel Alliance I’m blessed to be old enough to remember segregated travel and see the changes since then. In the 1950s, we took the train from my home in Chicago to Mississippi, we had to move to the segregated coach cars once we reached Cairo, Illinois, the last stop above the Mason-Dixon line. It was the law. And any road trip required you to pack your own food (it seemed to ALWAYS include fried chicken and pound cake, no matter who fixed it!) so you didn’t have to risk hostile encounters at restaurants. You could usually get soft drinks at gas stations, but there was no guarantee. The History Of Black Travel shows so many markers of progress since Jim Crow, but the price of progress is eternal vigilance.

Angle: Importance of storytelling perspective Davida Wulff-Vanderpuije , Destination Marketer & Travel Storyteller at WondersOfWanders.com Board Member, Communications Committee Co-Chair & Research Committee Member, Black Travel Alliance Black people have long nurtured a strong tradition of oral history, passing on stories and rituals from one generation to the next. Today, we are rewriting the script and telling unique tales of explorations to far-flung corners of the globe through our pens and lenses. In the History Of Black Travel Timeline , we have an incredible resource that showcases some of the pacesetters whose shoulders we stand on to continue telling our travel stories, our way.

Black Travel Alliance is a professional non-profit organization [501(c)(3)], created in 2020 to encourage, educate, equip and excel black travel professionals in education, media, and corporate positions. Our three pillars of the community are alliance, amplification, and accountability. As travel authors, bloggers, broadcasters, journalists, photographers, podcasters, social media influencers, and vloggers, we unify to amplify. We also aim to provide training and business support to our members, as well as hold destinations and travel brands accountable on the issue of diversity in travel marketing and storytelling. For more information, visit www.blacktravelalliance.org .

Tourism RESET is a multi-university and interdisciplinary research and outreach initiative that seeks to identify, study, and challenge patterns of social inequity in the tourism industry. Since its inception in 2010, Tourism RESET has advocated for anti-racism in travel, hospitality, and cultural tourism. Yet, Tourism RESET is also poised to address a broad swath of related struggles such as human trafficking in hospitality, animal welfare in tourism, accessibility, and the continuing power issues related to gender. Our partnerships include academic and industry partners in collaborating in various projects ranging from survey design, data analysis, in-depth interviews, focus groups, workshops, seminars, and grant writing. For more information, visit www.tourismreset.com .

- More Networks

Black History Month and the History of Black Travel

- February 27, 2023

By: Cambria Jones, Director of Marketing | SearchWide Global

While today marks the end of Black History Month, the impact and history of Black people extend well beyond the constraints of a calendar, especially as it relates to travel. We must have a heightened awareness and curiosity about how our industry has and continues to impact the travel experience for Black people.

Travel has always been a part of Black history. This dates back to 1492, when four African brothers accompanied Christopher Columbus on his first voyage , to the painful period beginning in 1619 of enslaved Africans being brought to the United States , followed by centuries of challenges leading up to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and continues today.

The Black Travel Alliance , in partnership with Tourism RESET , developed a History of Black Travel timeline of more than 130 entries highlighting the pioneers, groundbreakers, and events that have impacted and inspired Black travel.

Black History Month is a time to reflect on the challenges we’ve overcome, celebrate our victories, and inspire the future. As we look at this timeline, I encourage our industry to consider how we impact the travel experience for Black people beyond Black History Month. What are we doing to build communities where Black people feel comfortable, safe, and free to express themselves?

Connect With Us

The travel history of black america.

February 15, 2022 12:58 pm By Necoh Mitchell

February is Black History Month, and Independent Travel Advisor Necoh Mitchell, with LaVon Travel & Lifestyle, is helping us share some of the travel history of Black America. It’s important that black history isn’t separate from American history, and sharing our stories is the best way for it to be learned.

How about we start in the 1930s. People would spend their summers traveling by car to visit their families or maybe taking a trip to the beach. Black people didn’t have the freedom to travel just anywhere because Jim Crow laws and segregation prevented this. Angry people who didn’t want to see black travelers confirmed it. So, in 1936 Victor Hugo Green wrote “The Negro Motorist Green Book,” or simply, “The Green Book.” It was a travel guide for black people. Mr. Green published lodging, restaurants, and gas stations that did business with black people. This book kept them informed and safe from 1936 – 1966.

Moving to 1938, Willa Brown Chappell was the first American woman to get her private pilot’s license on June 22, 1938. Mrs. Chappell wasn’t finished with the travel industry, and in 1940 she co-founded the National Airmen’s Association of America, which was also the first black Aviator group. She and her husband also opened the first flight school owned by black people. She also became the first American woman to have both a mechanics (1935) and commercial aviation (1939) license. Talk about a phenomenal woman!

Going into the 1940s, there were enough black pilots who wanted to fly, but they weren’t permitted to use the airports. The answer? The Columbia Air Center. This was an airfield in Croom, Maryland, that was set up by black pilots in 1941. It had an all-black staff and trainers who served in World War II as Tuskegee Airmen. Columbia Air Center was open between 1941-1958. These pilots loved the skies and created a way to stay in them. They are truly an inspiration.

By the 1950s, the “Golden Age of Travel,” black people wanted to travel more domestically and internationally. So Freddye Henderson and her husband Jacob opened Henderson Travel Service in Atlanta, Georgia, to help them do just that. The travel agency booked thousands of trips for black travelers, including Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s, 1964 visit to Oslo, Norway, where he accepted the Nobel Peace Prize. The Henderson’s saw the potential of specializing in travel to Africa, so they provided services to go there, including chartering planes to West Africa where there were no commercial flights. They started to focus on trip planning and tours to Africa. They worked closely with almost all of the major African American professional associations, including the National Bar Association, National Medical Association, historically black colleges and universities, and more. Henderson Travel Service used their ingenuity and endurance to create a Travel Agency that black people could trust in to get to the far-flung corners of the earth. Their legacy has paved the way for so many to not only travel, but to work in the travel industry.

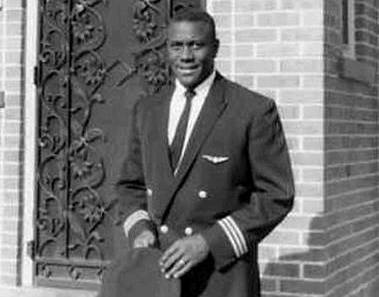

It wasn’t until 1956 that you saw a black person become a pilot for an airline. Perry H. Young, Jr., became the first on December 17, 1956, when he was hired by New York Airways. It was in 1965, nine years later, that Captain Marlon Dewitt Green became the first black man to be a pilot for a major U.S. airline, Continental Airlines. It took a lengthy court battle that went to the Supreme Court for him to achieve the right to fly with Continental Airlines. He flew with them from 1965 – 1978. When he died in 2010, Continental Airlines named a Boeing 737 after him. In 1978, Jill Elaine Brown became the first black woman to be hired as a pilot for a major airline , Texas International Airlines.

These tenacious ones paved the way for many little black boys and black girls who dream about traveling the world and working in the travel industry. We see the fruits of their labors. Black people spend over 95 billion dollars on travel. Myself, my family, and my friends contribute to that 95 billion.

We’re so grateful for Mr. Green, Ms. Chappell, the Hendersons, Mr. Young, Mr. Dewitt Green, Ms. Brown, and the Tuskegee Airmen for their contributions to travel. But is all great now? The short answer is no.

While we have organizations like The Organization of Black Aerospace Professionals and The National Association of Black Hotel Owners, Operators & Developers (NABHOOD), and Blacks In Tourism, we need more allies. These organizations are key, but ALL travel organizations should be inclusive of black people. Traveling in general should be a freeing experience for everyone. Unfortunately, that is not the case.

Black people do not always feel safe while traveling.

Black people are targeted while traveling.

Black people can be scared while traveling.

Awareness of racism is heightened, but the fact of the matter is – racism still exists. In order for black travel to just be travel, we need others to remember that we are people, not threats. While Black History Month is a great thing to promote awareness, we ask for participation in kindness year-round. Since 1976 we’ve recognized Black History Month in the United States. In those 46 years, it has highlighted some of the great achievements by the innovative and creative minds of Black Americans. Let’s continue to celebrate the incredible past and our inspired future.

I’m grateful to be a part of the community that is Tafari Travel where black people matter. They encourage diversity and look for ways to promote awareness. -- Necoh Mitchell

Author: Necoh Mitchell

Luxury Travel Advisor — Specializing in Eco Luxury Travel

solo.to/eco-necoh

Drexel Hill/Philadelphia, PA 267-713-9964

www.lavontravel.com

LaVon Travel & Lifestyle ~ A Virtuoso Affiliate

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

The Green Book: The Black Travelers’ Guide to Jim Crow America

By: Evan Andrews

Updated: March 13, 2019 | Original: February 6, 2017

“There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States. It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication for then we can go wherever we please, and without embarrassment.”

That was how the authors of the “Negro Motorist Green Book” ended the introduction to their 1948 edition . In the pages that followed, they provided a rundown of hotels, guest houses, service stations, drug stores, taverns, barber shops and restaurants that were known to be safe ports of call for African American travelers. The “Green Book” listed establishments in segregationist strongholds such as Alabama and Mississippi, but its reach also extended from Connecticut to California—any place where its readers might face prejudice or danger because of their skin color. With Jim Crow still looming over much of the country, a motto on the guide’s cover also doubled as a warning: “Carry your Green Book with you—You may need it.”

First published in 1936, the Green Book was the brainchild of a Harlem-based postal carrier named Victor Hugo Green. Like most Africans Americans in the mid-20th century, Green had grown weary of the discrimination blacks faced whenever they ventured outside their neighborhoods. Rates of car ownership had exploded in the years before and after World War II , but the lure of the interstate was also fraught with risk for African Americans. “Whites Only” policies meant that black travelers often couldn’t find safe places to eat and sleep, and so-called “ Sundown Towns ”—municipalities that banned blacks after dark—were scattered across the country. As the foreword of the 1956 edition of the Green Book noted, “the White traveler has had no difficulty in getting accommodations, but with the Negro it has been different.”

READ MORE: Was Jim Crow A Real Person?

Inspired by earlier books published for Jewish audiences, Green developed a guide to help black Americans indulge in travel without fear. The first edition of his Green Book only covered hotels and restaurants in the New York area, but he soon expanded its scope by gathering field reports from fellow postal carriers and offering cash payments to readers who sent in useful information. By the early 1940s, the Green Book boasted thousands of establishments from across the country, all of them either black-owned or verified to be non-discriminatory. The 1949 guide encouraged hungry motorists passing through Denver to stop for a bite at the Dew Drop Inn. Those looking for a bar in the Atlanta area were told to try the Yeah Man, Sportsman’s Smoke Shop or Butler’s. In Richmond, Virginia, Rest-a-Bit was the go-to spot for a ladies’ beauty parlor.

The Green Book’s listings were organized by state and city, with the vast majority located in major metropolises such as Chicago and Detroit. More remote places had fewer options—Alaska only had a lone entry in the 1960 guide —but even in cities with no black-friendly hotels, the book often listed the addresses of home owners who were willing to rent rooms. In 1954, it suggested that visitors to tiny Roswell, New Mexico, should stay at the home of a Mrs. Mary Collins.

READ MORE: How Freedom Rider Diane Nash Risked Her Life to Desegregate the South

The Green Book wasn’t the only handbook for black travelers—another publication called “Travelguide” was marketed with tagline “Vacation and Recreation Without Humiliation”—but it was by far the most popular. Thanks to a sponsorship deal with Standard Oil, the Green Book was available for purchase at Esso gas stations across the country. Though largely unknown to whites, it eventually sold upwards of 15,000 copies per year and was widely used by black business travelers and vacationers alike. In his memoir “ A Colored Man’s Journey Through 20th Century Segregated America ,” Earl Hutchinson Sr. described purchasing a copy in preparation for a road trip he and his wife took from Chicago to California. “The ‘Green Book’ was the bible of every Negro highway traveler in the 1950s and early 1960s,” he wrote. “You literally didn’t dare leave home without it.”

As its popularity grew, the Green Book expanded from a motorists’ companion to an international travel guide. Along with suggestions for the United States, later editions included information on airline and cruise ship journeys to places like Canada, Mexico, the Caribbean, Africa and Europe. “We know a number of our race who have a long standing love affair with the tempestuous city of Paris,” the 1962 Green Book noted. The guide also offered travel tips and feature articles on certain cities. The 1949 edition shined the spotlight on Robbins, Illinois, a town “owned and operated by Negroes.” In 1954, readers were encouraged to visit San Francisco, which was described as “fast becoming the focal point of the Negroes’ future.”

In offering advice to its readers, the Green Book adopted a pleasant and encouraging tone. It usually avoided discussing racism in explicit terms—one article simply noted that “the Negro travelers’ inconveniences are many”—but as the years passed it began to champion the achievements of the civil rights movement . In one of its last editions in 1963-64, it included a special “Your Rights, Briefly Speaking” feature that listed state statutes related to discrimination in travel accommodations. “The Negro is only demanding what everyone else wants,” the article stressed, “what is guaranteed all citizens by the Constitution of the United States.”

READ MORE: The Silent Protest That Kick-Started the Civil Rights Movement

Victor Hugo Green died in 1960 after more than two decades of publishing his travel guide. His wife Alma took over as editor and continued to release the Green Book in updated editions for a few more years, but just as Green had once hoped, the march of progress eventually helped push it toward obsolescence. In 1964, the Civil Rights Act finally banned racial segregation in restaurants, theaters, hotels, parks and other public places. Just two years later, the Green Book quietly ceased publication after nearly 30 years in print.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Search Please fill out this field.

- Manage Your Subscription

- Give a Gift Subscription

- Newsletters

- Sweepstakes

15 Inspiring Places in the U.S. to Learn About Black History

From Memphis to Boston, uncover important monuments, museums, and historical sites.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/vanessa-wilkins-1b9202b10956475e99e5385912316608.jpg)

Parks, monuments, and historic homes throughout the U.S. bear witness to the lasting cultural and historic achievements of Black residents over the centuries.

The legacy of Black Americans is often overlooked by the country at large, and it wasn't until November 2016 that the Smithsonian dedicated a national museum to African American history and culture . But traces from some of the country's most influential musicians, politicians, writers, and Civil Rights leaders can be found in just about every state.

Travelers may not have noticed some of the historic sites in their own cities and towns, such as the lunch counters where young people fought against segregation laws, or the African Meeting House in Boston, which is the oldest Black church in the country. Consider making a trip to one of these sites — only a small selection of the hundreds of locations where travelers can learn about Black heritage in the U.S.

Civil Rights Trail

This national trail includes over 100 locations across 15 states , educating visitors about the long and ongoing struggle of Black people to achieve equal rights. Locations include the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. and the Edmund Pettus Bridge, the location of a police confrontation during the Selma, Alabama marches.

National Museum of African American History and Culture, Washington, D.C.

Inaugurated in November 2016, this Smithsonian museum in Washington, D.C. is the "only national museum devoted exclusively to the documentation of African American life, history, and culture," according to its website . Objects on display include Chuck Berry's Cadillac, Harriet Tubman's prayer shawl, and protest signs from the Black Lives Matter movement. The Sweet Home Café in the museum showcases some of the stories and themes of the rest of the museum, giving visitors a taste of traditional meals from the diaspora. Taste spicy oxtail pepperpot or savor sweet potato pie.

Mississippi Civil Rights Museum and Museum of Mississippi History, Mississippi

These two museums attempt to take a critical look at the state's controversial history, particularly during the height of Jim Crow segregation laws in the 20th century.

The Civil Rights Museum, in particular, explores how Mississippi often served as a prime organizing ground for the movement in the 1960s. Protests such as the Freedom Rides and other forms of resistance against segregation often started in Mississippi, given its fierce segregation.

"These museums are telling the stories of Mississippi history in all of their complexity," said Katie Blount, director of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, which operates the two new museums, in a statement. "We are shying away from nothing. Understanding where we are today is shaped in every way by where we have come from in our past."

Beale Street Historic District, Memphis, Tennessee

This neighborhood in Memphis served as the incubator for some of the best early jazz, blues, and R&B music. Louis Armstrong, B.B. King, and Muddy Waters all played in this district's famed clubs, and Elvis spent a lot of time there as a teenager, listening to the blues music that would influence his rockabilly style.

Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, Kansas City, Missouri

Local historians and former baseball players helped create this Missouri museum , founded in 1990. The museum now occupies 10,000 square feet of space in a building shared with the American Jazz Museum. Visitors can explore photographs and interactive exhibits chronicling some of the most well-known Black baseball players, including Jackie Robinson and Buck O'Neil.

African Meeting House, Boston, Massachusetts

Built in the early 1800s, this small place of worship in the Beacon Hill neighborhood of Boston is one of the oldest historically Black churches in the country. The location served as a church, school, and meeting house where members of Boston's Black community organized, particularly during the push for the abolition of slavery in the 19th century.

Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, Washington, D.C.

Visitors can tour Douglass' historic house to learn about his lifetime of activism and writing. A leader in both the abolition and suffragette movements, Douglass fought for equal rights after escaping from slavery, going on to pen an autobiography about his experiences.

Museum of the African Diaspora, San Francisco, California

This San Francisco museum showcases contemporary art from across the African diaspora. Exhibits explore everything from slave narratives to the celebrations of Carnival in the Caribbean islands .

Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park, Church Creek, Maryland

A former enslaved person who went on to become a leader of the Underground Railroad, Harriet Tubman is one of the most iconic women in history. The land encompassing her home in upstate New York was named a national park in 2017 , ensuring its legacy.

"What makes her so incredibly striking is that she went back several times after her own escape to freedom to help others," Debra Michals , Ph.D. and director of women and gender studies at Merrimack College, told Travel + Leisure . "I don't think most people today could comprehend what kind of inner fortitude and dedication to the larger cause of freedom that that must have taken."

Colored Musicians Club, Buffalo, New York

The Colored Musicians Club in Buffalo, New York, is the only operating African American jazz club in the United States. Established in 1917, the historic club became a place for Black musicians to socialize, play music, and rehearse. It has hosted the likes of musical legends like Ella Fitzgerald and Duke Ellington. In 1999, the CMC was designated a historical preservation site, and the first floor of the building now serves as a multimedia museum for guests to listen to jazz and enjoy historic memorabilia.

National Museum of African American Music, Nashville, Tennessee