- Ask LitCharts AI

- Discussion Question Generator

- Essay Prompt Generator

- Quiz Question Generator

- Literature Guides

- Poetry Guides

- Shakespeare Translations

- Literary Terms

The Odyssey

Ask LitCharts AI: The answer to your questions

- Quizzes, saving guides, requests, plus so much more.

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Meta-Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Social Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Disability Studies

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

4 The ‘Nekyia’

- Published: March 2018

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

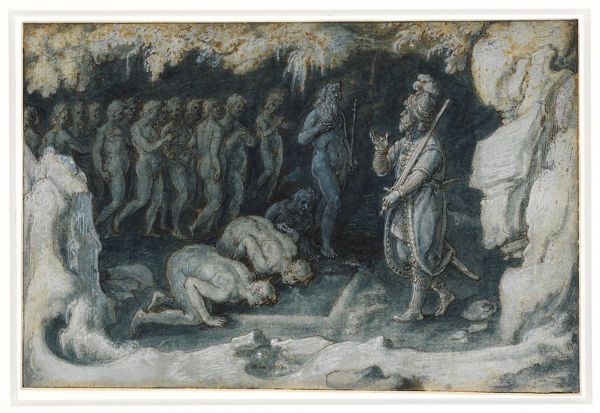

This chapter offers an analysis of the beginning of Odysseus’ Underworld journey in Odyssey 11. It follows closely the action as it develops in Odyssey 11 and it introduces the reader to the actual poetics of Hades through the discussion of the first encounters the hero has in Hades with his former companion Elpenor, the seer Teiresias, and his mother Antikleia. The chapter further offers an interpretation of the prophecy of Teiresias, which has often been seen as problematic by readers and scholars alike. This chapter shows that, on the contrary, it can be understood if it is seen through the lens of the poetics of Hades.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

History Cooperative

Odysseus: Greek Hero of the Odyssey

A Greek war hero, father, and king: Odysseus was all of this and then some. He miraculously survived the 10-year Trojan War and was the last of the veterans to return. However, his homeland – a humble island on the Ionian Sea – would evade him for another decade.

In the beginning, Odysseus and his men left the shores of Troy with 12 ships. The passage was not easy, being fraught with monstrosities and gods riled by the war’s aftermath. In the end, only Odysseus – one out of 600 comrades – returned home. And his home, the longing of which had propelled him forward thus far, had become a different type of battlefield.

In his time away during the war, over a hundred youths began lusting after Odysseus’ wife, his lands and title, and plotting to kill his beloved son. These circumstances became yet another trial the hero had to overcome. Now, equipped with naught but his cunning, Odysseus would once more rise to the occasion.

The story of Odysseus is full of twists and turns. Though at its heart, it echoes the story of a man doing whatever it took to make it home alive.

Table of Contents

Who is Odysseus?

Odysseus (a.k.a. Ulixes or Ulysses) is a Greek hero and the king of Ithaca, a small island on the Ionian Sea. He gained renown for his feats during the Trojan War , but it wasn’t until the journey home did he truly establish himself as a man worthy of being an epic hero.

During the events of the Trojan War in Homer’s Iliad , Odysseus was among many of Helen’s former suitors that were called to arms to retrieve her at the behest of her husband, Menelaus. Besides Odysseus’ military prowess, he was quite the orator: both full of guile and savvy. According to Apollodorus (3.10), Tyndareus – Helen’s stepfather – was concerned about bloodshed amongst the potential grooms. Odysseus promised to devise a plan to stop Helen’s suitors from killing one another if the Spartan king helped him “win the hand of Penelope.”

When Paris kidnapped Helen, Odysseus’ clever thinking came back to haunt him.

He became venerated in the hero cults of Greek religion. One such cult center was located in Odysseus’ homeland of Ithaca , in a cave along Polis Bay. More than this though, it is likely that the hero cult of Odysseus was spread as far as modern-day Tunisia, over 1,200 miles away from Ithaca, according to the Greek philosopher, Strabo.

READ MORE: History’s Most Famous Philosophers: Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and More!

Odysseus is the son of Laertes, King of the Cephallenians, and Anticlea of Ithaca. By the events of the Iliad and the Odyssey , Laertes is a widower and a co-regent of Ithaca.

What is Co-Regency?

After his departure, Odysseus’ father took over most of Ithaca’s politics. It was not unusual for ancient kingdoms to have co-regents. Both ancient Egypt and Biblical ancient Israel observed co-regency at numerous points in their histories.

Generally, a co-regent was a close family member. As is seen between Hatshepsut and Thutmose III , it was also occasionally shared with a spouse. Co-regencies are unlike diarchies, which were practiced in Sparta because co-regencies are a temporary arrangement. Diarchies, meanwhile, were a permanent feature in the government.

READ MORE: Egyptian Pharaohs: The Mighty Rulers of Ancient Egypt

It would be implied that Laertes would step down from official duties after Odysseus’ return to Ithaca.

Odysseus’ Wife: Penelope

As the most important person in his life besides his son, the wife of Odysseus, Penelope, plays a crucial role in the Odyssey . She is known for her stalwart approach toward her marriage, her intellect, and her role as an Ithacan queen. As a character, Penelope exemplifies ancient Greek womanhood . Even the ghost of Agamemnon – himself murdered by his wife and her lover – manifested and praised Odysseus on “what a fine, faithful wife you won!”

READ MORE: The Life of Women in Ancient Greece

Despite being married to the king of Ithaca, 108 suitors vied for Penelope’s hand during her husband’s long absence. According to her son Telemachus, the suitor composition was 52 from Dulichium, 24 from Samos, 20 from Zakynthos, and 12 from Ithaca. Granted, these guys were convinced Odysseus was super dead, but still moving into his home and accosting his wife for a decade is creepy . Like, beyond so.

For 10 years, Penelope refused to declare Odysseus dead. Doing so delayed public mourning , and made the suitor’s pursuits seem both unjustifiable and shameful.

On top of that, Penelope had a couple of tricks up her sleeve. Her legendary wit is reflected in the tactics she used to delay the hounding suitors. First, she claimed that she had to weave a death shroud for her father-in-law, who was getting on in years.

In ancient Greece , Penelope’s weaving of a burial shroud for her father-in-law was the epitome of filial piety. It was Penelope’s duty as the woman of the house in the absence of Laertes’ wife and daughter. Thus, the suitors had no choice but to lay off their advances. The ruse was able to delay the men’s advancements for three more years.

Odysseus’ Son: Telemachus

Odysseus’ son was just a newborn when his father left for the Trojan War . Thus, Telemachus – whose name means “far from battle” – grew up in a lion’s den.

The first decade of Telemachus’ life was spent during a massive conflict that robbed local wily youths of the guidance provided by an older generation. Meanwhile, he continued to grow into a young man in the years after the war. He struggles with his mother’s ceaseless suitors while simultaneously holding out hope for his father’s return. At some point, the suitors plot to kill Telemachus but agree to wait until he returns from searching for Odysseus.

Telemachus eventually gets sweet revenge and helps his father slaughter all 108 men.

It is worth noting that the original Homeric epic cites Telemachus to be Odysseus’ only child. Even so, that may not be the case. During his exploits back to Ithaca, Odysseus could have fathered up to six other children: seven kids in all. The existence of these spare children is up for debate since they are primarily mentioned in Hesiod’s Theogony and Pseudo-Apollodorus’ “Epitome” from Bibliotheca .

What is the Odysseus Story?

The story of Odysseus is a long one and begins in Book I of the Iliad . Odysseus disembarked for the war effort unwillingly but stayed until the bitter end. During the Trojan War, Odysseus put his all into keeping morale up and keeping casualties low.

At the end of the war, it took Odysseus another 10 years to get home and this journey is described in the Odyssey, Homer’s second epic poem. The first of the books, collectively known as The Telemachy , focuses entirely on Odysseus’ son. It isn’t until Book V do we revisit the hero.

Odysseus and his men earn the wrath of the gods, come face-to-face with horrifying monstrosities, and stare down their mortality in the eyes. They travel across the Mediterranean and Atlantic Seas, even passing by Oceanus at the ends of the Earth. At some point, Greek legend tells of Odysseus being the founder of modern Lisbon, Portugal (called Ulisipo during the Roman Empire ’s heyday).

While this is all going down, Odysseus’ wife, Penelope, struggles to maintain peace at home. Suitors insist that she should remarry. It is her duty, they believe, as her husband is likely long dead.

It is important to note that despite the death and loss that surrounds Odysseus on his journey home, his story is not qualified as a tragedy. He manages to successfully circumvent many of his trials and overcomes all obstacles in his path. Even the wrath of Poseidon couldn’t stop him.

In the end, Odysseus – the last of his crew – makes it home alive to Ithaca.

How are the Gods Represented in the Odyssey ?

Odysseus’ journey home was as tormenting as it was eventful thanks to the influence of the gods. Following Homeric tradition, the Odyssean gods were swayed by emotions and took easily to offense. Duty, pettiness, and lust drove the gods of the Odyssey to interfere with the hero’s journey home to rugged Ithaca.

Much of the time, Odysseus’ passage was barred by some mythological being or another. Some of the Greek gods that play their hand in the story of Odysseus are as follows:

Whereas Athena and Poseidon had a more pivotal role in the story, the other deities were sure to make their mark. The Ocean nymph Calypso and the goddess Circe acted simultaneously as lovers and hostage-takers. Hermes and Ino offered Odysseus aid in his times of need. Meanwhile, the likes of Zeus passed divine judgment with the sun god Helios pulling his arm.

Mythological monsters also threatened Odysseus’ voyage, including…

- Polyphemus the Cyclops

Monstrosities like Charybdis, Scylla, and the Sirens clearly pose a greater threat to Odysseus’ ship than the others on the list, but Polyphemus shouldn’t be trifled with either. If it weren’t for Odysseus blinding Polyphemus then they never would have left the island of Thrinacia. They’d all probably end up in Polyphemus’ stomach otherwise.

In all honesty, the wringer that Odysseus and his men are put through makes the Trojan War seem tame.

What is Odysseus Most Famous For?

The acclaim Odysseus has is largely in part because of his penchant for trickery. Honestly, the guy can really think on his feet. When we consider that his grandfather was a famous rogue, maybe it is safe to say it is hereditary.

One of his more infamous stunts was when he feigned insanity in an attempt to avoid the draft for the Trojan War. Picture this: a young king plowing salted fields, unresponsive to the world around him. It was going great until the Euboean prince Palamedes threw Odysseus’ infant son Telemachus in the way of a plow.

Of course, Odysseus swerved the plow to avoid hitting his child. Thus, Palamedes managed to disprove Odysseus’ madness. Without delay, the Ithacan king was sent to the Trojan War. Cunning aside, the man was catapulted forward as an epic hero when he remained decidedly loyal to the Greek war effort, neglecting his desire to return home.

Generally, the escapades of Odysseus and his men on their return voyage to Ithaca are what the world remembers the hero for. Though there is no denying that time and time again, Odysseus’ persuasive powers came in clutch to save the day.

Odysseus in the Trojan War

During the Trojan War, Odysseus played a significant part. When Thetis put Achilles into hiding to avoid his enlistment, it was Odysseus’ ruse that gave away the hero’s disguise. Furthermore, the man acts as one of Agamemnon’s advisors and displays great control over swaths of the Greek army at various points in time. He convinces the leader of the Achaeans to stay in a seemingly hopeless battle not once, but twice , despite his own strong desire to return home.

Moreover, he was able to console Achilles long enough after the death of Patroclus to give the Greek soldiers a much-needed break from combat. Agamemnon may have been the Achaean commander, but it was Odysseus who restored order to the Greek camp when tensions rose. The hero even returned the daughter of a priest of Apollo to put an end to a plague that befell the Greek army.

READ MORE: Apollo Family Tree: The Lineage of the Greek God of Light

Long story short, Agamemnon was given Chryseis, the daughter of the priest, as a slave. He was really into her, so when her father came bearing gifts and requesting her safe return, Agamemnon told him to kick rocks. The priest prayed to Apollo and boom , here comes the plague.

Oh, and the Trojan horse? Greek legend credits Odysseus as the brains of that operation.

Crafty as ever, 30 Greek warriors led by Odysseus infiltrated the walls of Troy. This Mission Impossible-style infiltration is what put an end to the 10-year conflict (and Trojan King Priam’s lineage).

Why Does Odysseus Go to the Underworld?

At some point on his perilous journey, Circe warns Odysseus of the dangers that await him. She informs him that if he desires a way home to Ithaca, he would have to seek out Theban Tiresias, a blind prophet.

The catch? Tiresias was long dead. They would have to travel to the Underworld, the House of Hades if they wanted to go home.

READ MORE: 10 Gods of Death and the Underworld From Around the World

Himself long-since exhausted, Odysseus admits that he “wept as I sat on the bed, nor had my heart any longer desire to live and behold the light of the sun” ( Odyssey , Book X ). Ithaca seemed further than ever before. When Odysseus’ men discovered their next destination, the hero describes how “their spirit was broken within them, and sitting down right where they were, they wept and tore their hair.” Odysseus and his men, all mighty Greek warriors, are horrified at the idea of going to the Underworld.

The mental and emotional toll of the journey was evident, but it was only just beginning.

Circe directs them to a grove of Persephone across from “deep eddying Oceanus .” She even describes the exact way they had to go about calling forth the dead and the animal sacrifices they would have to make thereafter.

When the crew reached the Underworld, countless wraiths emerged from Erebus : “brides, and unwedded youths…toil-worn old men…tender maidens…and many…that had been wounded…men slain in fight, wearing…blood-stained armor.”

The first of these spirits to approach Odysseus was one of his men, a youth named Elpenor that died intoxicated in a fatal fall. He was an ataphos , a spirit wandering that did not receive a proper burial. Odysseus and his men had neglected such, being too caught up in their voyage to Hades.

READ MORE: Hades Family Tree: A Family of Hades, Greek God of the Dead

Odysseus also witnessed the spirit of his mother, Anticlea, before Tiresias appeared.

How Did Odysseus Get Rid of the Suitors?

After 20 years gone, Odysseus returns to his homeland of Ithaca. Before going further, Athena disguises Odysseus as a poor beggar to keep his presence on the island on the down low. Odysseus’ true identity is then revealed only to Telemachus and a select number of loyal servants.

By this time, Penelope was at the end of her line. She knew that she could delay the gaggle of admirers no longer. The men – all 108 – were given a challenge by the Ithacan queen: they had to string and shoot Odysseus’ bow, sending the arrow cleanly through several axeheads.

Penelope knew that only Odysseus could string his bow. There was a trick to it that only he knew. Even though Penelope was fully aware of this, it was her last chance to defy the suitors.

Consequently, each suitor failed to string the bow, let alone shoot it. It was a massive blow to their confidence. They began to disparage the thought of marriage. There were other women available, they lamented, but to fall so exceedingly short of Odysseus was embarrassing.

Finally, a disguised Odysseus hobbled forward: “…wooers of the glorious queen…come, give me the polished bow…I may prove my hands and strength, whether I have yet might such as was of old in my supple limbs, or whether by now my wanderings and lack of food have destroyed it” ( Odyssey , Book XXI ). Despite protest from the admirers, Odysseus was permitted to try his hand. The servants loyal to their lord were tasked with locking exits.

In a blink, Odysseus dropped the face reveal of the Bronze Age. And he’s armed.

You could hear a pin drop. Then, slaughter ensued. Athena shielded Odysseus and his allies from the suitor’s defenses all while helping her favorites strike true. All 108 suitors were killed.

Why Does Athena Help Odysseus?

The goddess Athena plays a central role in Homer’s epic poem, Odyssey . More so than any other god or goddess. Such is undeniably true. Now, just why she was so willing to offer her aid is worth exploring.

First things first, Poseidon, the Greek god of the sea , has it out for Odysseus. As the saying goes, “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.” Athena has had a bit of a grudge against Poseidon ever since they competed for the patronage of Athens. After Odysseus managed to blind Poseidon’s Cyclops son, Polyphemus, and earns the sea god’s ire, Athena had even more of a reason to get involved.

READ MORE: Poseidon Family Tree: The Divine Lineage of the Ancient Greek God of the Sea

Secondly, Athena already has a vested interest in Odysseus’ family. For much of the Odyssey , she acts as a guardian for both Odysseus and young Telemachus. While this likely comes down to their heroic bloodline, Athena also makes it known that she is Odysseus’ patron goddess. Their relationship is confirmed in Book XIII of the Odyssey when Athena exclaims, “…yet you did not recognize Pallas Athene, Daughter of Zeus, who always stands by your side and guards you through all your adventures.”

In all, Athena helps Odysseus because it is her duty. She must fulfill her duty just as the other gods must. Truth be told, having her charge cross Poseidon is just a bonus for her.

Who Killed Odysseus?

The epic Odyssey leaves off with Odysseus making amends with the families of Penelope’s suitors. Ithaca is prosperous, pleasant, and most of all peaceful when the story comes to a close. From that, we can garner that Odysseus lived out the rest of his days being a family man.

The man deserves it after everything he went through. Unfortunately, you can probably see where this is going: that just isn’t the case.

In the Epic Cycle – a collection of poems recounting pre- and post-Trojan War events – a lost poem known as Telegony immediately succeeds Odyssey. This poem chronicles the life of Telegonus, Odysseus’ young son born from the hero’s affair with the sorceress Circe.

With a name meaning “born afar,” Telegonus sought out Odysseus when he came of age. After a series of blunders, Telegonus finally came face-to-face with his old man…unknowingly, and in a skirmish.

During the confrontation, Telegonus strikes the killing blow to Odysseus, stabbing him with a poisoned spear gifted by Athena. Only in Odysseus’ dying moments did the two recognize each other as father and son. Heartbreaking, but Telegonus’ story doesn’t end there.

After a possibly very awkward family reunion on Ithaca, Telegonus brings Penelope and Telemachus back to his mother’s island, Aeaea. Odysseus is buried on the beach and Circe turns everyone else present immortal. She ends up settling down with Telemachus and, with her youth regained, Penelope remarries…Telegonus.

Was Odysseus Real?

The fantastic Homeric epics of ancient Greece still ignite our imaginations. There’s no denying that. Their humanness tells a more uniquely human story than other tales of the time. We can look back on the characters – god and man-like – and see ourselves reflected back to us.

When Achilles mourns the loss of Patroclus in the Iliad , we feel his sorrow and desperation; when the women of Troy are separated, raped, and enslaved, our blood boils; when Poseidon refuses to forgive Odysseus for blinding his son, we understand his resentment.

Regardless of how real the characters of Homer’s classic epics are to us, there is no tangible evidence of their existence. Obvious gods aside, even the lives of the mortals involved cannot be concretely verified. This means that Odysseus, a beloved character for generations, likely did not exist. At least, not as a whole.

If there was an Odysseus, his exploits would have been exaggerated, if not borrowed wholly from other individuals. Therefore, Odysseus – the hypothetically real Odysseus – could have been a great king of a minor Ionian island during the Bronze Age. He could have had a son, Telemachus, and a wife that he adored. Truth be told, the real Odysseus may have even participated in a large-scale conflict and was considered missing in action.

This is where the line is drawn. The fantastical elements that adorn Homer’s epic poems would be distinctly lacking, and Odysseus would have to navigate a stark reality.

What is Odysseus the God Of?

Does having a cult dedicated to your triumphs make you a god? Eh, it depends.

It is important to consider what constitutes a god in Greek myth. Generally, gods were mighty immortal beings. This means they cannot die, at least not by any usual means. Immortality is one of the reasons Prometheus could endure his punishment, and why Cronus was able to be diced up and tossed into Tartarus .

In some cases, powerful gods could reward individuals with immortality, but this was uncommon. Usually, mythology only mentions demigods becoming gods since they were already divinely inclined. Dionysus is a good example of this because he, despite being born mortal, became a god after ascending Olympus.

READ MORE: Olympian Gods

The worship of heroes in ancient Greece was a normal, localized thing. Offerings were made to the heroes, including libations and sacrifices. Occasionally, heroes were even communed with when the locals needed advice. They were thought to influence fertility and prosperity, though not as much as a city god would.

Saying that, a hero cult becomes established after said hero’s death. By Greek religious standards, heroes are viewed more as ancestral spirits than any sort of deity.

Odysseus earned his hero acclaim through his brave and noble feats, but he is not a god. In fact, unlike many Greek heroes, Odysseus isn’t even a demi-god. Both of his parents were mortals. However, he is the great-grandson of Hermes : the messenger god is the father of Odysseus’ maternal grandfather, Autolycus, a famous trickster and thief.

READ MORE: 11 Trickster Gods From Around The World

Roman Opinion of Odysseus

Odysseus may be a fan favorite in Greek myths, but that doesn’t mean he saw the same popularity with the Romans. In fact, many Romans link Odysseus directly to the fall of Troy.

For some background, Romans oftentimes identified themselves as the descendants of Prince Aeneas of Troy. After Troy fell to the Greek army, Prince Aeneas (himself a son of Aphrodite ) led survivors to Italy. They became the progenitors of the Romans.

READ MORE: Aphrodite Family Tree: A Family of the Greek Goddess of Love

In the Aeneid , Virgil’s Ulysses typifies a common Roman bias : the Greeks, despite their apt cunning, are immoral. While Hellenism gained traction throughout the Roman Empire , Roman citizens – especially those belonging to the upper echelons of society – viewed the Greeks through a narrow elitist lens.

They were impressive people, with vast knowledge and rich culture – but, they could be better (i.e. more Roman).

However, the Roman people were as varied as any other, and not all shared such a belief. Numerous Roman citizens looked upon how Odysseus approached situations with admiration. His roguish ways were ambiguous enough to be comically applauded by the Roman poet Horace, in Satire 2.5 . Likewise, “cruel Odysseus,” the deceitful villain, was celebrated by the poet Ovid in his Metamorphoses for his skill in oration ( Miller, 2015 ).

Why is Odysseus Important to Greek Mythology?

The importance of Odysseus to Greek mythology extends far beyond Homer’s epic poem, Odyssey . He gained renown as one of the most influential Greek champions, commended for his cunning and bravery in the face of adversity. Moreover, his misadventures throughout the Mediterranean and Atlantic Seas grew into a staple of the Greek Hero Age, equivalent to the maritime feats of Jason and the Argonauts .

More than anything, Odysseus figures centrally as one of Greece’s glittering heroes of ages past. When all is said and done, the Iliad and the Odyssey take place during the Hero Age of Greek mythology. It was during this time that the Mycenaean civilization dominated much of the Mediterranean.

READ MORE: Ancient Civilizations Timeline: The Complete List from Aboriginals to Incans

Mycenaean Greece was immensely different than the Greek Dark Ages that Homer grew up in. In this way, Odysseus – as with many of Greece’s most famous heroes – represents a lost past. A past that was filled with daring heroes, monsters, and gods. For this reason, Odysseus’ tale supersedes the obvious messages of Homer’s epics.

Sure, the tales act as a warning against violating xenia , the Greek concept of hospitality and reciprocity. And, yes, Homer’s epic poems brought to life the Greek gods and goddesses that we know today.

Despite the above, the biggest contribution Odysseus gives to Greek mythology is being a significant part of their lost history. His actions, decisions, and cunning acted as a catalyst for innumerable key events throughout the Iliad and Odyssey , respectively. These events – from the oath sworn by Helen’s suitors to the Trojan horse – all impacted Greek history.

As Seen in O Brother, Where Art Thou? And Other Media

From film adaptations to television and plays, the epics of Homer are a hot topic.

One of the more famous films to emerge in recent years is the comedy-musical, O Brother, Where Art Thou? released in 2000. With a star-studded cast and George Clooney as the leading man, playing Ulysses Everett McGill (Odysseus), the movie was a hit. Pretty much, if you like the Odyssey but would love to see it with a Great Depression twist then you’ll enjoy this film. There are even Sirens!

On the flip side of things, there have been attempts at more faithful adaptations in the past. These include the 1997 miniseries, The Odyssey , with Armand Assante as Odysseus, and a 1954 film starring Kirk Douglas, Ulysses . Both have their pros and cons, but if you’re a history buff then both are uniquely admirable.

Even video games couldn’t resist paying homage to the late Ithacan king. God of War: Ascension has Odysseus as a playable character in multiplayer mode. His armor set is otherwise available for Kratos, the main character, to wear. Comparatively, Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey is more of a reference to the epic highs and lows of Bronze Age seafaring Odysseus experienced.

How to Cite this Article

There are three different ways you can cite this article.

1. To cite this article in an academic-style article or paper , use:

<a href=" https://historycooperative.org/odysseus-greek-hero-of-the-odyssey/ ">Odysseus: Greek Hero of the Odyssey</a>

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

- Find a course

- Undergraduate study

- Postgraduate study

- MPhil/PhD research

- Short courses

- Entry requirements

- Financial support

- How to apply

- Come and meet us

- Evening study explained

- International Students

- Student Services

- Business Services

- Student life at Birkbeck

- The Birkbeck Experience

- Boost your career

- About Birkbeck

- Contact Birkbeck

- Faculties and Schools

- ReciteMe accessibility

Journeys to the Underworld in Classical Literature and Culture

- Credit value : 30 credits at Level 5

- Convenor and tutor : Professor Catharine Edwards

- Assessment : two 2500-word essays (25% each) and a 48-hour online examination (50%)

Module description

Greco-Roman conceptions of the underworld represent it as strictly for the dead, a place from which there is no return. Yet the story of a living hero daring to descend to the underworld - and to come back - features already in Homeric epic. Odysseus makes the perilous journey to Hades to interrogate the ghosts of his companions, also encountering his dead mother.

The underworld descent and return was familiar enough in fifth-century Athens to become the stuff of comedy in the hand of Aristophanes, whose Frogs centres around the journey of Dionysus to the underworld (which turns out to be full of feuding tragic poets). Descent to the underworld is appropriated to philosophic ends by Plato in his Phaedo . Virgil offers a Roman reworking of Odysseus’ journey in his Aeneid , where Aeneas goes down to the underworld and, guided by the ghost of his own father, is given foresight into Rome’s future. Ovid, in his Metamorphoses , a radical reworking of the epic form, gives his own version of Orpheus’ journey.

- What exactly is at stake in these accounts of descent to the underworld?

- Can we usefully detach myths from the literary contexts in which they are recounted?

- What is the relationship between these underworld narratives and religious beliefs?

- What happens when Virgil reworks Homer?

During this module we will explore these diverse underworld-journey narratives to interrogate the relationship between myth and literature in Greco-Roman antiquity.

The Odyssey Book IX - Nekuia, in Which Odysseus Speaks to Ghosts

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

- Study Guides

- Authors & Texts

- Top Picks Lists

- Best Sellers

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

An Unusual Purpose

- Poseidon's Wrath

Advice From a Siren

The greek underworld, tiresias and anticlea, other women, heroes and friends.

- M.A., Linguistics, University of Minnesota

- B.A., Latin, University of Minnesota

Book IX of The Odyssey is called Nekuia, which is an ancient Greek rite used to summon and question ghosts. In it, Odysseus tells his King Alcinous all about his fantastic and unusual trip to the underworld in which he did just that.

Usually, when mythic heroes undertake the dangerous voyage to the Underworld , it's for the purpose of bringing back a person or animal of value. Hercules went to the Underworld to steal the three-headed dog Cerberus and to rescue Alcestis who had sacrificed herself for her husband. Orpheus went below to try to win back his beloved Eurydice, and Theseus went to try to abduct Persephone . But Odysseus ? He went for information.

Although, obviously, it is frightening to visit the dead (referred to as the home of Hades and Persephone "aidao domous kai epaines persphoneies"), to hear the wailing and weeping, and to know that at any moment Hades and Persephone could make sure he never sees the light of day again, there is remarkably little peril in Odysseus' voyage. Even when he violates the letter of the instructions there are no negative consequences.

What Odysseus learns satisfies his own curiosity and makes a great story for King Alcinous whom Odysseus is regaling with tales of the fates of the other Achaeans after the fall of Troy and his own exploits.

Poseidon's Wrath

For ten years, the Greeks (aka Danaans and Achaeans) had fought the Trojans. By the time Troy (Ilium) was burned, the Greeks were eager to return to their homes and families, but much had changed while they'd been away. While some local kings were gone, their power had been usurped. Odysseus, who ultimately fared better than many of his fellows, was to suffer the wrath of the sea god for many years before he was permitted to reach his home.

"[ Poseidon ] could see him sailing upon the sea, and it made him very angry, so he wagged his head and muttered to himself, saying, heavens, so the gods have been changing their minds about Odysseus while I was away in Ethiopia, and now he is close to the land of the Phaeacians, where it is decreed that he shall escape from the calamities that have befallen him. Still, he shall have plenty of hardship yet before he has done with it." V.283-290

Poseidon refrained from drowning the hero, but he threw Odysseus and his crew off course. Waylaid on the island of Circe (the enchantress who initially turned his men into swine), Odysseus spent a luxurious year enjoying the bounty of the goddess. His men, however, long restored to human form, kept reminding their leader of their destination, Ithaca . Eventually, they prevailed. Circe regretfully prepared her mortal lover for his trip back to his wife by warning him that he would never make it back to Ithaca if he didn't first speak with Tiresias.

Tiresias was dead, though. In order to learn from the blind seer what he needed to do, Odysseus would have to visit the land of the dead. Circe gave Odysseus sacrificial blood to give to the denizens of the Underworld who could then speak to him. Odysseus protested that no mortal could visit the Underworld. Circe told him not to worry, the winds would guide his ship.

"Son of Laertes, sprung from Zeus, Odysseus of many devices, let there be in thy mind no concern for a pilot to guide thy ship, but set up thy mast, and spread the white sail, and sit thee down; and the breath of the North Wind will bear her onward." X.504-505

When he arrived at Oceanus, the body of water encircling the earth and the seas, he would find the groves of Persephone and the house of Hades, i.e., the Underworld. The Underworld is not actually described as being underground, but rather the place where the light of Helios never shines. Circe warned him to make the appropriate animal sacrifices, pour out votive offerings of milk, honey, wine, and water, and fend off the shades of the other dead until Tiresias appeared.

Most of this Odysseus did, although before questioning Tiresias, he talked with his companion Elpenor who had fallen, drunk, to his death. Odysseus promised Elpenor a proper funeral. While they talked, other shades appeared, but Odysseus ignored them until Tiresias arrived.

Odysseus provided the seer with some of the sacrificial blood Circe had told him would permit the dead to speak; then he listened. Tiresias explained Poseidon's anger as the result of Odysseus' blinding Poseidon's son (the Cyclops Polyphemus , who had found and eaten six members of Odysseus' crew while they were taking shelter in his cave). He warned Odysseus that if he and his men avoided the herds of Helios on Thrinacia, they would reach Ithaca safely. If instead, they landed on the island, his starving men would eat the cattle and be punished by the god. Odysseus, alone and after many years of delay, would reach home where he would find Penelope oppressed by suitors. Tiresias also foretold a peaceful death for Odysseus at a later date, at sea.

Among the shades, Odysseus had seen earlier had been his mother, Anticlea. Odysseus gave the sacrificial blood to her next. She told him that his wife, Penelope, was still waiting for him with their son Telemachus, but that she, his mother, had died from the ache she felt because Odysseus had been away so long. Odysseus longed to hold his mother, but, as Anticlea explained, since the bodies of the dead were burned to ash, the shades of the dead are just insubstantial shadows. She urged her son to talk with the other women so he would be able to give news to Penelope whenever he reached Ithaca.

Odysseus briefly talked to a dozen women, mostly good or beautiful ones, mothers of heroes, or beloved of the gods: Tyro, mother of Pelias and Neleu; Antiope, mother of Amphion and the founder of Thebes, Zethos; Hercules' mother, Alcmene; Oedipus' mother, here, Epicaste; Chloris, mother of Nestor, Chromios, Periclymenos, and Pero; Leda, mother of Castor and Polydeuces (Pollux); Iphimedeia, mother of Otos and Ephialtes; Phaedra; Procris; Ariadne; Clymene; and a different type of woman, Eriphyle, who had betrayed her husband.

To King Alcinous, Odysseus recounted his visits to these women quickly: he wanted to stop speaking so he and his crew could get some sleep. But the king urged him to go on even if it took all night. Since Odysseus wanted help from Alcinous for his return voyage, he settled down to a more detailed report on his conversations with the warriors beside whom he had fought so long.

The first hero Odysseus spoke with was Agamemnon who said Aegisthus and his own wife Clytemnestra had killed him and his troops during the feast celebrating his return. Clytemnestra wouldn't even close her dead husband's eyes. Filled with distrust of women, Agamemnon gave Odysseus some good advice: land secretly in Ithaca.

After Agamemnon, Odysseus let Achilles drink the blood. Achilles complained about death and asked about his son's life. Odysseus was able to assure him that Neoptolemus was still alive and had repeatedly proved himself to be brave and heroic. In life, when Achilles had died, Ajax had thought the honor of possessing the dead man's armor should have fallen to him, but instead, it was awarded to Odysseus. Even in death Ajax held a grudge and would not speak with Odysseus.

Next Odysseus saw (and briefly recounted to Alcinous) the spirits of Minos (son of Zeus and Europa whom Odysseus witnessed meting out judgment to the dead); Orion (driving herds of wild beasts he had slain); Tityos (who paid for violating Leto in perpetuity by being gnawed upon by vultures); Tantalus (who could never quench his thirst despite being immersed in water, nor slake his hunger despite being inches from an overhanging branch bearing fruit); and Sisyphus (doomed forever to roll back up a hill a rock that keeps rolling back down).

But the next (and last) to speak was Hercules' phantom (the real Hercules being with the gods). Hercules compared his labors with those of Odysseus, commiserating on the god-inflicted suffering. Next Odysseus would have liked to have spoken with Theseus, but the wailing of the dead scared him and he feared Persephone would destroy him using the head of Medusa :

"I would fain have seen - Theseus and Peirithoos glorious children of the gods, but so many thousands of ghosts came round me and uttered such appalling cries, that I was panic stricken lest Persephone should send up from the house of Hades the head of that awful monster Gorgon." XI.628

So Odysseus finally returned to his men and his ship, and sailed away from the Underworld through Oceanus, back to Circe for more refreshment, comfort, a burial, and help to get home to Ithaca.

His adventures were far from over.

Updated by K. Kris Hirst

- 'The Odyssey' Themes and Literary Devices

- 'The Odyssey' Quotes Explained

- Summary of Odyssey Book IV

- 'The Odyssey' Overview

- 'The Odyssey' Summary

- 'The Odyssey' Characters: Descriptions and Significance

- Overview of Homeric Epithets

- 'The Odyssey' Vocabulary

- Death and Dying in "The Iliad"

- Summary of the Iliad Book I

- Summary of Homer's Iliad Book XXIII

- Tiresias: Ovid's Metamorphoses

- Studying the Bible as Literature

- 'Animal Farm' Questions for Study and Discussion

- 'Wuthering Heights' Themes, Symbols, Literary Devices

Cahiers des études anciennes

Accueil Numéros LIII Localization of the Odyssey’s Und...

Localization of the Odyssey ’s Underworld

Entrées d’index, index de mots-clés : , texte intégral.

- 1 On ancient and modern localization of Odysseus’ journey, see my webpage « In the Wake of Odysseus (...)

1 Locating the Odyssey ’s Underworld would seem to be a ridiculous endeavor. The Odyssey is vague about how Odysseus reaches the Underworld ; its description of Hades is sketchy. And Hades is a supernatural place : how could one discover its location ? Indeed, those intent on following in the wake of Odysseus, no matter how enthusiastic, often steer clear of the Underworld 1 . But many since Antiquity have localized the Odyssean Underworld, or at least its entrance. Others forego reality and theorize about the abstract cosmography implied by Odysseus’ journey to the Hades. Between these extremes of real-world localization and mental mapping lie a wide variety of arguments, with different implications about the Homeric epic. Concentrating on Odysseus’ journey to the Underworld, I will explore how the geography and spatiality of the wanderings of Odysseus have been variously conceptualized.

- 2 The most comprehensive collection of localization is by A. Wolf & H.‑H. Wolf, Die Wirkliche Reise (...)

2 There are many different types of Homeric localization. Modern books that purport to trace the « real » journey of Odysseus are typically written by amateurs outside of academia, or at least classical studies. Some are composed by sensationalists claiming that Odysseus sailed across the Atlantic or around the world 2 . But those recounting autoptic visitation of Mediterranean locales, besides providing entertainment as travel writing, can be of interest to Homerists. Examples of what I will call « popular localization » will be discussed towards the end of the paper.

- 3 For criticism of localization, cf . A. Heubeck, « Books IX-XII », in A. Heubeck , S. West & J. B. Ha (...)

- 4 J. S. Romm , The Edges of the Earth in Ancient Thought , Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1992 (...)

- 5 Cf . A. Heubeck, op. cit. , p. 4‑5, where ancient and modern localization are conflated as equally « (...)

3 « Why bother ? », you may ask 3 . Popular localizers lead their readers through a close (if tendentious) reading of the wanderings, and they often reference relevant ancient testimony. Their arguments may not persuade us, but their method is comparable to other conceptions of the relation of the journey of Odysseus to the real world. The ancients habitually linked the wanderings of Odysseus to locations in the Mediterranean. I refer not just to geographers like Eratosthenes and Strabo 4 ; Greek and Roman inhabitants of Italy and Sicily believed that Odysseus had visited their lands. This was not idle whimsy ; ancient localization involved serious matters of origins and genealogy 5 . Homerists have theorized about the real world provenance of Odysseus’ journey and explored its cosmographical implications. Methods of connecting the wanderings to Mediterranean places vary greatly, but recurring tendencies are discernible. By comparing and contrasting the diverse ways in which the Homeric Underworld has been conceptualized, we can better frame our own approach to the Odyssey ’s underworld episode. I will start with a close reading of the Underworld in the Odyssey before turning to cosmographical localization, geographical localization, and finally popular localization.

- 6 For a well theorized study of spatial perspective in the Odyssey ’s narrative, see A. Purves , Space (...)

4 Though localization can be simplistic, it exists on a continuous spectrum with Homeric research, which, after all, is another form of reception. Professionals as well as amateurs are interested in the spatial aspects of the Homeric poem 6 . Scholarship has often explored the underworld episode’s provenance in the real world and its abstract cosmography. By considering the diversity of ways in which the Homeric Underworld has been conceptualized, we can better frame our own approach to the Odyssey ’s underworld episode.

I - The Homeric Underworld

5 As has long been recognized, Book XI of the Odyssey seems to begin as a necromancy (the summoning of shades of the dead) before evolving into a kat á basis (a heroic journey to the Underworld by a mortal). The seeming disjunction between necromancy and catabasis in the Homeric episode, as well as suspicions of interpolation for such sections as the catalogue of women, the punishment of sinners, and the appearance of Heracles, has encouraged scepticism about the unity of Odyssey XI. In my analysis I will treat the whole of the episode as authentic, and in particular I do not consider the presence of both necromantic and catabatic elements to be poetically problematic. But the seeming conflation of the two has led to very different ways of localizing the scene. The necromantic nature of the episode has tempted some to see real-world nekuomanteîa as foundational for Homer’s Underworld. The Odyssey ’s explicit placement of the Underworld at the edge of the earth has inspired others to visualize Odysseus’ journey as movement through an abstract cosmography.

6 Before exploring geographical and cosmographical interpretations of the Homeric Underworld, we should consider how the Odyssey itself portrays it. Information about Odysseus’ travel to the Underworld is very limited. When Odysseus announces his intention to leave Circe, she consents but states the necessity of first undertaking a journey to the home of Hades and Persephone (XI, 490-491). Odysseus in dismay points out that nobody has travelled to Hades in a ship (502). Circe replies that his ship will reach Hades without guidance, under the force of the north wind (506-507). When he has travelled through Oceanus ( δι ' Ὠκεανοῖο περήσῃς , 508), she adds, and reaches the « shore and groves of Persephone » (509), with poplars and willows, he should beach the ship « at Oceanus » ( ἐπ ' Ὠκεανῷ , 511). Then he is to proceed to the home of Hades, where the Pyriphlegethon and Kokytos, the latter an offshoot of the Styx, flow together into the Acheron river by a rock (512-515). Circe provides no further spatial information except for the directive to turn the sacrificial animals towards Erebus while facing back towards the « streams of the river » (528-529). The river is apparently Oceanus ; Erebus, literally « darkness », would then refer to the region of Hades, as commonly.

- 7 Odysseus similarly questions Elpenor (57-58) about how he reached Hades by foot, which reminds one (...)

7 The actual journey to Hades seems to proceed as foretold by Circe, though the direction of the guiding wind is not specified (XI, 10), and there is some additional information. Odysseus recalls that the ship sailed all day until the sun set (11-12), and then reached the « limits » ( πείραθ ' , 13) of Oceanus. There, the Phaeacians are told, is where the Cimmerians live, under everlasting night (14-19). The Greeks proceeded « along the stream of Oceanus » (21) until they came to the place specified by Circe. Odysseus does not report that he followed Circe’s directional advice for the sacrifice, but he states that souls immediately gathered from « Erebus » (36-37). Odysseus then sits, except when he tries to embrace his mother, and allows only certain souls to approach and drink the sacrificial blood in order to speak (a conceit that eventually fades from the telling). Of further relevance is Teiresias’ observation that Odysseus « leaving the light of the sun » came to see the dead, and Anticleia’s surprise that her living son could cross rivers and Oceanus, which she claims is possible by ship but not by foot (155-159) 7 . It has been noticed that Odysseus replies that necessity brought him down to Hades ( κατήγαγεν , 164). Catabatic terms to describe the journey are employed elsewhere : when the shade of Achilles asks how Odysseus dared to come down to Hades ( κατελθέμεν , 475), and when Odysseus himself says to Penelope that he went down into the house of Hades ( κατέβην δόμον Ἄϊδος εἴσω , XXIII, 252).

8 After Odysseus has conversations with several heroes who approach him, in some unexplained manner he is able to view souls inside Hades. When Odysseus and the men leave, the current carries the ship on Oceanus ( κατ ' Ὠκεανὸν ποταμὸν , 639), with the men rowing until a wind of unnamed direction impels it. The ship leaves the current of Oceanus (XII, 1) and reaches the flow of the sea ( κῦμα θαλάσσης , 2), and eventually Aeaea, where the house of Dawn is located and Helios rises (3-4). Further demarcation of the Underworld is given in the second nékyia in Book XXIV. Here Hermes guides the souls near « the streams of Oceanus », a « white rock », the gates of Helios, and the place of dreams (11-12). Then they find the shades in a field of asphodel (13), where Odysseus had earlier observed shades (XI, 539 ; 573).

II - Homeric cosmography

- 8 See G. S. Kirk , J. E. Raven & M. Schofield , The Presocratic Philosophers , Cambridge, Cambridge Uni (...)

- 9 Cf . Iliad VII, 421-423 ; VIII, 485 ; XIX, 433-434 ; Odyssey X, 191 ; XII, 374-388 ; XXIV, 12 ; Hom (...)

- 10 Key sources are Mimnermus 11a West ; Stesichorus fr. 185 PMG ; see further T. Gantz , Early Greek M (...)

- 11 D. Ogden , Greek and Roman Necromancy , Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2001, discusses heroi (...)

- 12 C. Sourvinou-Inwood , Reading Greek Death , Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1995, p. 56-65, describes Odyss (...)