- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Goats and Soda

- Infectious Disease

- Development

- Women & Girls

- Coronavirus FAQ

'The Crown' Says One Dance Changed History. The Truth Isn't So Simple

Tim McDonnell

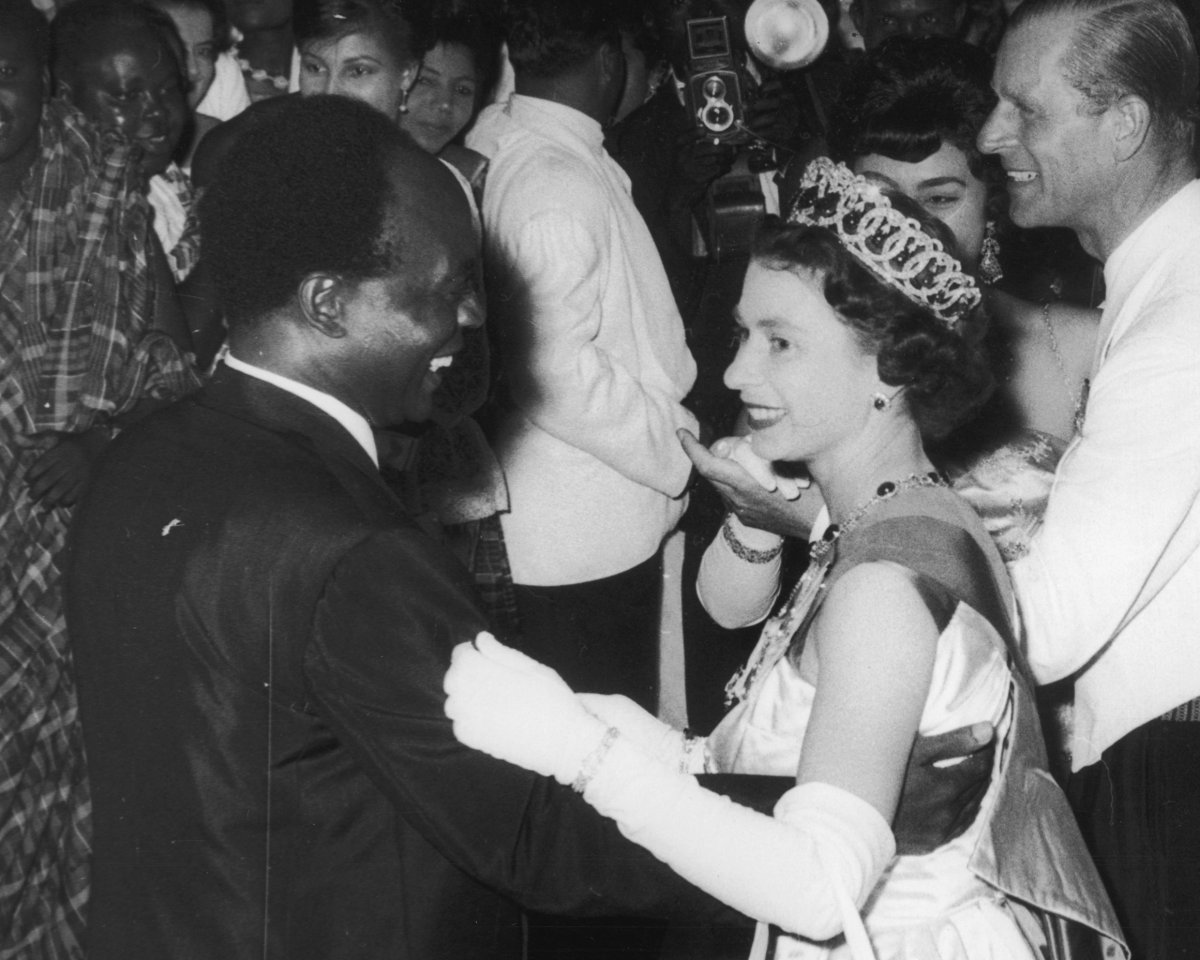

Queen Elizabeth II dances with Ghanaian president Kwame Nkrumah at a ball in Accra, Ghana, in 1961. Central Press/Getty Images hide caption

Queen Elizabeth II dances with Ghanaian president Kwame Nkrumah at a ball in Accra, Ghana, in 1961.

It was a highlight of the latest season of the Netflix series The Crown , which chronicles the early years of Queen Elizabeth II's reign: The year is 1961, the Cold War is heating up and the queen (played by Claire Foy), feeling self-conscious after learning that First Lady Jackie Kennedy (Jodi Balfour) called her "incurious" at a dinner party, decides to take a more proactive role in dealing with Ghana, a former colony whose new leader, Kwame Nkrumah (Danny Sapani), appears to be getting too cozy with the Soviets.

Season 2 Of 'The Crown' Exposes The Royal Family's Fitful Evolution

Her solution: A dance with Nkrumah at a ball in the capital, Accra. The foxtrot, specifically, to the extreme, hilarious consternation of Prime Minister Harold Macmillan (Anton Lesser).

It's a high-stakes political gamble that could decide the balance of Soviet power in Africa, which in the early 1960s was fast emerging as a Cold War battleground. To everyone's relief, the dance is a success. The implication is that, in exchange for his photo op dancing with the queen, Nkrumah will "come back to the fold" and squash Soviet hopes for Africa. Later, JFK (Michael Hall) crows to Jackie that her jab at the queen precipitated a major foreign policy victory for the U.S. and U.K. It's the foxtrot that changes the course of history.

"Well, that's nice," says Nat Nuno-Amarteifio , an architect and amateur historian who served as mayor of Accra from 1994-98 and remembers the queen's supposedly fateful visit from when he was a teenage student. "It's a lot of bulls**t."

'The Crown' Creator Peter Morgan

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

It turns out The Crown got a lot wrong about that dance, according to Nuno-Amarteifio and other Ghanaian history experts.

There's no dispute that the Ghana visit happened, or that Nkrumah and the queen shared a dance, as shown in the photo above. But the dance wasn't exactly a pivotal moment for Nkrumah's political philosophy, which continued to adhere to socialism in subsequent years, even earning him the Lenin Peace Prize the year after the queen's visit.

"I'm surprised that the dance has attained this retroactive reputation," Nuno-Amarteifio says. "Nobody talked about it then."

At the time, Nkrumah was likely Africa's most influential leader. As a young man in the mid-1930s, he had scraped together enough cash from his farming family in what was then the British colony of Gold Coast to travel to the U.S. for an education. He worked his way through philosophy and theology degrees at Lincoln College and the University of Pennsylvania, followed by two years in London forming alliances with other anti-colonial organizers who were poised to dislodge Britain, France and other colonial powers from their seats in Africa. In 1947, when a pro-independence party began to gather momentum in Accra, its members recruited Nkrumah as their leader. He returned to Gold Coast, but soon found himself imprisoned in a converted British beach fort after a strike he helped organize turned violent. Still, at the next election in 1951, he ran for office from his cell and won a seat in Parliament. As his party's leader, he was installed as prime minister, and the British had no choice but to release him.

Over the next several years he helped coax the country toward independence, under the watchful eye of a British governor. During that time, he nurtured a cult of personality, promoted by newspapers as a kind of towering superhero who would soon vanquish the imperialists who had occupied the country for nearly a century. Sure enough, in 1957 Nkrumah succeeded in passing legislation granting Ghana full self-government, making it the first colony in sub-Saharan Africa after South Africa to gain independence. The independence celebration in Accra was attended by political leaders from across the globe, including Vice President Richard Nixon (according to historian Martin Meredith's The Fate of Africa , Nixon infamously asked a black guest at the party how it felt to be free, to which the man reportedly replied, "I wouldn't know, sir. I'm from Alabama.").

That party featured another royal dance, a prelude to Nkrumah's encounter with the queen several years later. Meredith recounts that Nkrumah was warned he would need to dance with the Duchess of Kent, who would be there to represent the Crown. But Nkrumah was ill-trained in Western dance and only felt comfortable with highlife , a West African pop style. It fell to another guest, Louis Armstrong's wife, Lucille, to teach him the foxtrot.

During the country's early years, Nkrumah committed to the socialist sentiments he had first picked up in the U.S. and London, with the belief that a centrally planned economy and state control of cocoa and other valuable industries — what Nkrumah and others took to calling "African socialism" — were essential for the new country to shake the chains of colonialism. This was very concerning to President Kennedy, who in 1962 called Africa "the greatest open field of maneuver in the worldwide competition between the communist bloc and the non-communist." But it was not unique; several other newly-independent African nations, including Kenya, Mali and Tanzania, took guidance from the USSR, which, according to Meredith, "seemed to show that socialism produced rapid modernization."

In The Crown , that embrace is dramatized by a scene in which a portrait of the queen is taken down in the Ghanaian parliament building and replaced with one of Lenin. But although Nkrumah did tour Eastern Europe, his attachment to the USSR was never so extreme, Nuno-Amarteifio recalls.

"Our roots with Russian communism were more intellectual than anything else," he says. "There was nothing visceral about it. Lenin wasn't a personality that we associated with liberty or freedom. If anything, 99 percent of Ghanaians wouldn't have known who Lenin was."

John Parker , an historian at the University of London's School of Oriental and African Studies, agreed that Nkrumah's ties to socialism were mostly ideological and detached from specific foreign policy agreements with the USSR. Still, Nkrumah was seen as a wild card by the U.S. and U.K., and the queen's visit was part of a broader strategy (not an individual impulse, as represented in the show) to corral him and other rogue leaders.

"The British government was certainly concerned to limit Soviet influence in ex-colonies," Parker says. "Overseas tours by the queen were designed broadly to strengthen Commonwealth links."

Meanwhile, African socialism wasn't exactly working the way Ghanaians hoped it would. By the time of the queen's visit in 1961, the economy was crumbling, bribes were routinely collected by government officials at every level of the system (including by Nkrumah himself, who, according to Meredith, even set up a special state-run company to facilitate bribe collection from foreign businessmen) and political opponents were frequently jailed.

"There was a lot of unhappiness, and Nkrumah's position was already delicate," Nuno-Amarteifio says. "If the queen was brave to come to Ghana, he was also brave to welcome her, because it exposed him to tremendous embarrassment should anything happen. The whole world would be watching."

Fortunately, the event seems to have gone off smoothly. As for the dance itself, Nuno-Amarteifio says it barely registered with him and his friends at the time. If anything, he says, The Crown 's depiction of the ecstatic Ghanaian press and bewildered British bureaucrats, shocked that the queen would deign to dance with an African, comes across as paternalistic.

"It was a young white woman dancing with an African," he says. "What do you expect me to do, applaud?"

Did the visit accomplish anything? The big hydroelectric dam referenced in the episode was eventually built, not by the USSR but by an Italian company with financing from the U.S. and U.K. But "Ghana did not 'sever links' with the USSR," Parker says. "To suggest that [the dance] — or the royal tour as a whole — "tipped the balance" of Soviet power in West Africa is untrue."

Nkrumah would remain a proponent of socialism the rest of his life. In 1966, while on a trip to North Korea and China, he was deposed in a military coup that was likely orchestrated by the CIA.

In other words, the episode not only makes much ado out of a forgettable moment but uses that representation to manufacture a victory for the U.S. and U.K. that never really happened. Or, as Nuno-Amarteifio puts it: "I still don't know why that stupid dance is so important."

Tim McDonnell is a journalist covering the environment, conflict and related issues in sub-Saharan Africa. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram .

- soviet union

- Queen Elizabeth II

- Kwame Nkrumah

How Queen Elizabeth II's Controversial Trip to Ghana Changed the Future of the Commonwealth

To aid growing tensions, five days before Elizabeth's trip was to begin, bombs went off in the capital city of Accra. A statue of Nkrumah was hit, which showed the president was a target. Concerns about the queen possibly becoming collateral damage while with him were heightened.

Queen Elizabeth insisted on going to Ghana despite the danger involved

But Elizabeth had always been intent on making the trip to Ghana, and the bombings didn't alter this determination. One reason she was reluctant to reschedule was that she'd already canceled on Nkrumah in 1959 when she became pregnant with Prince Andrew . And though Ghana was part of the Commonwealth, along with other nations that had been part of the British Empire, she knew Nkrumah was getting restless. As head of the Commonwealth, the queen didn't want to insult or embarrass Ghana by postponing the visit, which could push Nkrumah into leaving the group altogether.

In addition, the queen was aware that Nkrumah was getting closer to the Soviet Union, which wanted to expand its foothold in Africa amidst the Cold War. The Ghanaian leader had even traveled to Moscow that October. Soviet attentions toward Nkrumah apparently led to Elizabeth feeling a bit competitive; at one point she declared, "How silly I should look if I was scared to visit Ghana and then [Soviet leader Nikita] Khrushchev went and had a good reception." Elizabeth also told her prime minister, "I am not a film star. I am the head of the Commonwealth — and I am paid to face any risks that may be involved. Nor do I say this lightly. Do not forget that I have three children."

Her visit was a success from start to finish

From the moment Elizabeth arrived in Ghana, along with Prince Philip , she was surrounded by crowds and excitement. Post-independence, the country had embarked on a program of "African socialism" in an attempt to strengthen its economy after years of colonialism. A neo-Marxist Ghanaian paper found Elizabeth to be "the world’s greatest Socialist Monarch in history." It was an unusual description for an enormously wealthy hereditary head of state, but indicated how popular she was.

At a state dinner, Nkrumah toasted Elizabeth by saying, "The wind of change blowing through Africa has become a hurricane. Whatever else is blown into the limbo of history, the personal regard and affection which we have for Your Majesty will remain unaffected." The queen's reply touched on the fact that nations of the Commonwealth could disagree without members needing to leave.

Elizabeth also captured attention by dancing with Nkrumah. Having the queen and a former colonial subject arm-in-arm on the dance floor was a way to demonstrate her acceptance of a new footing between their countries.

The trip had lasting effects on the Commonwealth

Nkrumah wasn't happy when Elizabeth went to visit the young son of an imprisoned opposition leader during her time in Ghana. But this didn't affect the overall impact of her trip. With the goodwill she'd generated, there was no more talk of Ghana leaving the Commonwealth.

Elizabeth's journey also helped Ghana get highly sought-after funding for the Volta Dam, a hydroelectric project that was a centerpiece of Nkrumah's economic plans. Once she'd returned, Macmillan contacted President John F. Kennedy to say, "I have risked my queen. You must risk your money." Financial backing from the Americans for the project soon came through, which cut off a potential avenue of influence for the Soviets.

Elizabeth's dedication to the Commonwealth meant that this trip would have been a success simply for helping to hold that organization together. However, the visit also demonstrated how, even as a monarch with limited powers, she still had a role to play on the world stage.

Kensington Palace Shares an Update on Kate

Prince William

Where in the World Is Kate Middleton?

Princess Kate Is Seen for First Time Since Surgery

Napoleon and Josephine Had a Stormy Relationship

The Most Iconic Photos of Prince George

King Charles III

Who’s Who in the British Line of Succession

How King Charles Reacted to Prince Harry’s Visit

The True Story of Princess Margaret’s Death

Prince Harry

Accessibility Links

Queen dancing in Ghana: The story behind her iconic visit to save the Commonwealth

Despite warnings of violence, elizabeth ii was determined to go to ghana and keep the african republic in the fold.

T he Queen danced gaily with Ghana’s president in 1961, seemingly unaware that their dance was a symbolic moment in the history of the Commonwealth.

Elizabeth II is pictured beaming on the dancefloor with President Nkrumah, whom the West had feared was getting too close to the Soviet Union, at a farewell ball in Accra. Despite bombings in the capital, the Queen had insisted on this tour to make sure the unstable African republic did not leave the Commonwealth.

In The Queen: Her Commonwealth Story , to be broadcast tonight, Ghanaian historian Nat Nunoo Amarteifio said that the Queen was gallant to visit because the Commonwealth could have easily become an almost white-only club.

Remembering the dance, he said: “A man could not have done it

Queen Elizabeth II and Africa: From an iconic dance in Ghana to friendship with Mandela

Elizabeth II maintained special ties with Britain’s former colonies and the members of the Commonwealth states in Africa. From the beginning of her reign in Kenya to her memorable meetings with Kwame Nkrumah and Nelson Mandela, the Queen had a long-standing relationship with the African continent.

Issued on: 10/09/2022 - 17:54 Modified: 10/09/2022 - 17:56

Elizabeth II visited Africa 21 times during her 70-year reign. According to the British Royal Family’s website, the Queen had visited nearly every country in the Commonwealth, yet some overseas visits were more impactful than others. Her first trip was particularly important.

On February 6, 1952, Princess Elizabeth and her husband Philip , already parents of Charles, born in 1948, and Anne, born in 1950, found themselves in the heart of the Aberdare mountain range, in central Kenya. They planned to spend a night at Treetops, a game-viewing lodge located 7,000 kilometres from England.

In the morning, the news came: George VI, Britain’s monarch for the last 15 years, had just died at the age of 56. With his death, the crown passed down to his eldest daughter, then in a distant country that was not yet a member of the Commonwealth – Kenya would not join until 1963. Elizabeth II would not learn of the death of her father until after her departure from Treetops, but it was in that hotel that her reign began.

"I am quite certain that this is one of the most wonderful experiences the Queen or the Duke of Edinburgh have ever had," read a letter dated February 8, 1952, written by an aide to the royal couple, responsible for thanking the owners of the hotel. Treetops burned down in 1954 and a new, much larger establishment has been built since then.

Elizabeth II briefly returned to Kenya in March 1972. In November 1983, she and her husband stayed in the country for four days and returned to Treetops, the lodge where she found herself when she became queen. This time she and her husband were more formally dressed. The Queen set foot in Kenya for the last time in October 1991.

On Friday, September 9, 2022, Uhuru Kenyatta, the outgoing president of Kenya and son of Jomo Kenyatta, the former president who welcomed the Queen in 1972, paid tribute to Elizabeth II in a message of condolence. "Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II was a towering icon of selfless service to humanity and a key figurehead of not only the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth of Nations, where Kenya is a distinguished member, but the entire world," he wrote.

I have received news of the death of Queen Elizabeth II and I send condolences to the people of the United Kingdom. The queen’s leadership of the Commonwealth for the past seven decades is admirable. pic.twitter.com/PT3Fv6ws7u — William Samoei Ruto, PhD (@WilliamsRuto) September 8, 2022

Kenya's new President-elect William Ruto also paid tribute to the Queen on Thursday, hailing her "admirable" leadership of the Commonwealth. "May her memories continue to inspire us. We join the Commonwealth in mourning and offer our condolences to the Royal Family and to the United Kingdom," he said, after describing the evolution of the Commonwealth as a testament to "the historic legacy" of the Queen.

In Ghana, an iconic dance with Kwame Nkrumah

Of all her tours in Africa, the one at the end of 1961 was among the most crucial, says Meriem Amellal Lalmas, a journalist at FRANCE 24. The Queen decided to travel to Ghana from November 9 to 20, despite opposition from the British press and politicians, who were wary of a visit at a time when Kwame Nkrumah, then the Ghanaian president, was drifting towards authoritarianism. Winston Churchill himself, a mentor to Elizabeth II, even called the prime minister at the time, Harold Macmillan, and asked him to convince the Queen not to visit the country that had declared its independence in 1957.

The sovereign refused to cancel the visit. She knew her visit was eagerly awaited. The upcoming birth of her third child, Andrew, had already forced her to cancel the trip in 1959 and Nkrumah had taken it badly. To ease tensions, the royal family had invited him to Balmoral, where the head of state had spent a few days with the Queen. Later, Prince Philip travelled to Ghana and promised an upcoming visit from his wife.

It was a high-stakes visit. Nkrumah, a Marxist, was cosying up to the Soviet bloc at the time and threatened to slam the door on the Commonwealth. Upon her arrival, the British Queen was very well received by the Ghanaian authorities. However, it was during a ball organised in her honour that she managed to turn the tide of public opinion: in front of the world’s cameras, she danced with the president of Ghana.

"This image seems mundane today but in this context, it was extremely avant-garde. It was a white woman dancing with a black man, it was the ruler of an empire dancing with a subject, as he was then considered, even if he is also the father of pan-Africanism and Ghanaian independence ", explains Meriem Amellal Lalmas.

The Queen's visit did not prevent Nkrumah from getting closer to the Soviet bloc, but it did stop Ghana breaking away from the Commonwealth. The Queen reassured the president and helped him obtain funding. Nkrumah later declared: “The winds of change blowing through Africa have become a hurricane. Whatever else is blown into the limbo of history, the personal regard and affection which we have for Your Majesty will remain unaffected.”

Last Thursday, Ghana's current president, Nana Akufo-Addo, was the first head of state to react to Elizabeth II’s death. On Twitter, he wrote: "As Head of the Commonwealth of Nations, she superintended over the dramatic transformation of the Union, and steered it to pay greater attention to our shared values and better governance. She was the rock that kept the organisation sturdy and true to its positive beliefs. We shall miss her inspiring presence, her calm, her steadiness, and, above all, her great love and belief in the higher purpose of the Commonwealth of Nations, and in its capacity to be a force for good in our world."

Nelson Mandela, the friend from South Africa

A member of the Commonwealth since its foundation, South Africa was a special country for Elizabeth II. She toured the country on her first trip to the African continent, in 1947. It was there, on her 21 st birthday, on April 21, 1947, that the future queen declared in a speech that she would dedicate her life to the service of the Commonwealth.

Faithful to the tradition of neutrality, the Queen did not speak out against apartheid until the end of the racist regime. In his book "Great Britain and the World" (ed. Armand Colin), the historian Philippe Chassaigne explains that Elizabeth II did not want to go to South Africa again "because it would have meant supporting the policy of apartheid”. She was only able to provide discreet support to Brian Mulroney, the Canadian prime minister who was campaigning for economic sanctions against South Africa in the beginning of the 1980s. Margaret Thatcher, then British prime minister, was on the opposite side.

The complicated relationship between Elizabeth II and Margaret Thatcher was also embodied in the United Kingdom's approach to Nelson Mandela : while the "Iron Lady" considered the African National Congress (ANC), the party of Madiba, a "terrorist organisation", the Queen reached out to the future South African leader who had spent 27 years in prison. Shortly after his release in 1990, she welcomed Nelson Mandela to the United Kingdom. When Mandela won the presidential election five years later, the queen traveled to South Africa to meet with him.

Previously, in 1991, Elizabeth II broke with protocol by inviting Mandela to the Commonwealth Summit in Harare, Zimbabwe, even though he did not have the required rank to attend the Queen's banquet. The Queen, aware of the symbolic significance of this invitation, had already lost some of her reserve when she said that she was content to see the end of apartheid.

Reacting to the Queen's death, the Mandela Foundation published a press release on Friday evoking the very friendly relationship between these two major figures of the 20th century: "They also talked on the phone frequently, using their first names with each other as a sign of mutual respect as well as affection [. . .] In the years following his release, Nelson Mandela cultivated a close bond with the queen”, whom he had nicknamed “Motlalepula” (“come with the rain”), after her 1995 visit which was marked by torrential rains.

Complicated relations with Robert Mugabe's Zimbabwe

The only country in Africa to have left the Commonwealth, Zimbabwe had been a complicated and cumbersome partner for Queen Elizabeth II. In 2002, the organisation decided to suspend the country from its Council, as a way of sanctioning of the presidential election organised that year. Elected in 1990 and re-elected in 1996, President Robert Mugabe won against Morgan Tsvangirai with 56.20% of the vote in an election marked by violence and fraud.

A year later, Zimbabwe decided to slam the door of the Commonwealth, outraged to learn that the organisation wanted to maintain its suspension. Robert Mugabe took the opportunity to describe the Commonwealth as an organisation run by "racist whites". In 2008, he was newly re-elected, with 90.22% of the vote, in a race that was once again denounced by many democracies in the world.

In June 2008, the crack between London and Robert Mugabe grew wider: David Miliband, the minister of foreign affairs, proposed to strip the Zimbabwean president of his honorary knighthood, which had been awarded to him in 1994, with the approval of Elizabeth II. "This decision was taken as a sign of revulsion at the human rights abuses and abject disregard for the democratic process in Zimbabwe under the rule of President Mugabe," the British Foreign Ministry wrote in a statement.

This article is a translation of the original in French.

Daily newsletter Receive essential international news every morning

Take international news everywhere with you! Download the France 24 app

- Queen Elizabeth II

- Commonwealth

- Nelson Mandela

- British Royal Family

The content you requested does not exist or is not available anymore.

- Entertainment

What The Crown Gets Right About Queen Elizabeth II's History-Making Trip to Ghana

Updated on 2/13/2018 at 6:44 PM

:upscale()/2017/12/17/025/n/1922283/883094b589563387_TheCrown_208_Unit_03066_R.jpg)

If there's one thing that Netflix's The Crown gets right (and occasionally wrong ), it's the details. The streaming giant's sprawling historical drama about the rise of Queen Elizabeth II (Claire Foy) is a stunning masterpiece that pulls directly from real-life events, footage, quotes, and letters to construct a compelling and realistic narrative about the life of the British royal family. Season two dives even deeper into iconic milestones from the monarch's impressive reign, including a 1961 dinner with President John F. Kennedy and First Lady Jackie Kennedy at Buckingham Palace , which is rumored to have had a hand in spurring on the queen's bold choice to visit Accra, the capital of Ghana.

After hearing rumors that the first lady considered her to be conservative and stuck in her ways, Queen Elizabeth reportedly decided to take action. Tensions were running high between Britain and Ghana, a commonwealth nation, so she decided to step in herself despite strong backlash from both her personal advisers and members of parliament. "I am not a film star," the queen said to then-Prime Minister Harold Macmillan . "I am the head of the Commonwealth — and I am paid to face any risks that may be involved. Nor do I say this lightly. Do not forget that I have three children."

Against the wishes of those around her due to bombing incidents in the country, Queen Elizabeth moved forward with her plans, which is portrayed in a later season two episode. Although not every single word that was shared between the queen and Ghana's Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah can be known for sure, the broad strokes of her visit — which included a beautiful dance with the king at a party thrown in her honor — seem to line up with history. As far as clothing goes, The Crown 's costume designers also nailed it. Elizabeth wears an understated, pale yellow dress and matching hat when she touches down in Ghana and later dons a beautiful cream ball gown when she makes her momentous decision to dance with Nkrumah.

See the real-life photos side by side with Netflix's interpretation ahead!

:upscale()/2017/12/17/025/n/1922283/0f65c54933c4d371_TheCrown_208_Unit_00542_R.jpg)

Editor's note: an earlier version of this article referred to Kwame Nkrumah's title as King and has been updated.

- Queen Elizabeth II

- Entertainment

- Sports Sports Betting Podcasts Better Planet Vault Mightier Autos Newsletters Unconventional Vantage Experts Voices

- Subscribe for $1

- Sports Betting

- Better Planet

- Newsletters

- Unconventional

How Queen Elizabeth II Danced With Ghana's President Months After Civil Rights Bus Bomb

Queen Elizabeth II showed her anti-racism credentials when she sparked global headlines by dancing with Ghana's president in 1961—while America was still facing segregation, a historian tells Newsweek .

Prince Harry and Meghan Markle leveled racism allegations at an unnamed royal who they said expressed concern about how dark baby Archie's skin would be before he was born.

However, the couple were quick to rule out Queen Elizabeth II and her husband, Prince Philip, as possible suspects.

While Philip, who left hospital after four weeks yesterday, has been accused of racism numerous times in the past, the queen herself has placed the Commonwealth at the heart of her role.

In 1961, in the height of the cold war, Britain and America feared Ghana would leave the Commonwealth and fall under the influence of the Soviet Union, U.K. newspaper The Times reported.

Up stepped the queen, then 35, on a mission to persuade President Kwame Nkrumah not to leave the partnership of nations she cherished.

During a visit to capital city Accra, the queen was photographed dancing happily with the Ghanaian leader at a time when black people in America were still denied the right to vote.

Robert Lacey, who charted Harry's feud with Prince William in Battle of Brothers , told Newsweek Meghan's racism allegations had not dented Britain's belief in the Queen's commitment to diversity.

He said: "Whatever the implications of alleged racism, nobody in their heart feels that's true of the Queen herself.

"I remember when I was growing up in 1961, there was a photograph of the Queen dancing in the arms of President Nkrumah of Ghana.

- Meghan and Prince Harry 'Frustrated' With Royal Racism Scandal: Gayle King

- Prince Philip Out of Hospital After Heart Surgery and Infection

- How Meghan Markle's Bombshell Royal Allegations Severely Damaged Both Sides

"There was shock horror around the world, not least in the still segregated United States that is pointing the finger at Britain now.

"It showed a commitment to diversity that the Queen's maintained throughout her life. You've seen the evidence.

"There's just been so much testimony to it."

It's easy to underestimate the power of such a simple act 60 years on, but the November dance came just six months after Ku Klux Klan members firebombed a bus of "Freedom Riders."

The civil rights protesters were attempting to demonstrate how the 1960 Supreme Court ruling in Boynton v. Virginia , banning segregation on interstate buses, was not being enforced in parts of the American south.

So they rode across state lines on Greyhound buses with black and white people sitting together, knowing they were at risk of attack, NPR reported.

On May 4, 1961, Ku Klux Klan members attacked one of the buses in Anniston, Alabama, throwing in a firebomb and then holding the doors shut.

Quoted on NPR , an extract of Raymond Arsenault's Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice reads: "They were all lucky to be alive.

"Several members of the mob had pressed against the door screaming, 'Burn them alive' and 'Fry the goddamn n******,' and the Freedom Riders had been all but doomed until an exploding fuel tank convinced the mob that the whole bus was about to explode."

As the racist mob retreated, the protesters were able to climb to freedom, engulfed in smoke.

Ghanaian historian Nat Nunoo Amarteifio told 2018 documentary The Queen: Her Commonwealth Story how Elizabeth's dance showed the respect she had for Nkrumah.

He said: "A man could not have done it. Here is our president, being respected enough by the Queen of England for her to put her arms around him. She was fairly graceful."

Professor Philip Murphy, director of the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, told The Times the dance showed how the queen was not resistant to de-colonization and wanted a new relationship with countries that had been part of Britain's empire.

He said: "There was a very warm personal dynamic between the Queen and Nkrumah and I think that has tremendous symbolic importance.

"It is showing that the Queen at least accepts the process of the ending of Empire and embraces something which is a multiracial, voluntary, friendly association of independent nations."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Jack Royston is Newsweek's Chief Royal Correspondent based in London, U.K. He reports on the British royal family—including King Charles III, Prince William, Kate Middleton, Prince Harry and Meghan Markle—and hosts The Royal Report podcast . Jack joined Newsweek in 2020; he previously worked at The Sun, INS News and the Harrow Times. Jack has also appeared as a royal expert on CNN, MSNBC, Fox, ITV and commentated on King Charles III's coronation for Sky News. He reported on Prince Harry and Meghan's royal wedding from inside Windsor Castle. He graduated from the University of East Anglia. Languages: English.

You can find him on Twitter at @jack_royston and his stories on Newsweek's The Royals Facebook page .

You can get in touch with Jack by emailing [email protected].

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.

- Newsweek magazine delivered to your door

- Newsweek Voices: Diverse audio opinions

- Enjoy ad-free browsing on Newsweek.com

- Comment on articles

- Newsweek app updates on-the-go

Top stories

What Hollywood Will Look Like in 10 Years

Donald Trump Leads Joe Biden in Every Battleground State: Polling Averages

Hay Fever Alert As Allergist Warns of 'Pollen Storm'

Columbia Protest Organizer Khymani James Takes Aim at AOC Amid Backlash

'The Crown' Says One Dance Changed History. The Truth Isn't So Simple

It was a highlight of the latest season of the Netflix series The Crown , which chronicles the early years of Queen Elizabeth II's reign: The year is 1961, the Cold War is heating up and the queen (played by Claire Foy), feeling self-conscious after learning that First Lady Jackie Kennedy (Jodi Balfour) called her "incurious" at a dinner party, decides to take a more proactive role in dealing with Ghana, a former colony whose new leader, Kwame Nkrumah (Danny Sapani), appears to be getting too cozy with the Soviets.

Her solution: A dance with Nkrumah at a ball in the capital, Accra. The foxtrot, specifically, to the extreme, hilarious consternation of Prime Minister Harold Macmillan (Anton Lesser).

It's a high-stakes political gamble that could decide the balance of Soviet power in Africa, which in the early 1960s was fast emerging as a Cold War battleground. To everyone's relief, the dance is a success. The implication is that, in exchange for his photo op dancing with the queen, Nkrumah will "come back to the fold" and squash Soviet hopes for Africa. Later, JFK (Michael Hall) crows to Jackie that her jab at the queen precipitated a major foreign policy victory for the U.S. and U.K. It's the foxtrot that changes the course of history.

"Well, that's nice," says Nat Nuno-Amarteifio , an architect and amateur historian who served as mayor of Accra from 1994-98 and remembers the queen's supposedly fateful visit from when he was a teenage student. "It's a lot of bulls**t."

It turns out The Crown got a lot wrong about that dance, according to Nuno-Amarteifio and other Ghanaian history experts.

There's no dispute that the Ghana visit happened, or that Nkrumah and the queen shared a dance, as shown in the photo above. But the dance wasn't exactly a pivotal moment for Nkrumah's political philosophy, which continued to adhere to socialism in subsequent years, even earning him the Lenin Peace Prize the year after the queen's visit.

"I'm surprised that the dance has attained this retroactive reputation," Nuno-Amarteifio says. "Nobody talked about it then."

At the time, Nkrumah was likely Africa's most influential leader. As a young man in the mid-1930s, he had scraped together enough cash from his farming family in what was then the British colony of Gold Coast to travel to the U.S. for an education. He worked his way through philosophy and theology degrees at Lincoln College and the University of Pennsylvania, followed by two years in London forming alliances with other anti-colonial organizers who were poised to dislodge Britain, France and other colonial powers from their seats in Africa. In 1947, when a pro-independence party began to gather momentum in Accra, its members recruited Nkrumah as their leader. He returned to Gold Coast, but soon found himself imprisoned in a converted British beach fort after a strike he helped organize turned violent. Still, at the next election in 1951, he ran for office from his cell and won a seat in Parliament. As his party's leader, he was installed as prime minister, and the British had no choice but to release him.

Over the next several years he helped coax the country toward independence, under the watchful eye of a British governor. During that time, he nurtured a cult of personality, promoted by newspapers as a kind of towering superhero who would soon vanquish the imperialists who had occupied the country for nearly a century. Sure enough, in 1957 Nkrumah succeeded in passing legislation granting Ghana full self-government, making it the first colony in sub-Saharan Africa after South Africa to gain independence. The independence celebration in Accra was attended by political leaders from across the globe, including Vice President Richard Nixon (according to historian Martin Meredith's The Fate of Africa , Nixon infamously asked a black guest at the party how it felt to be free, to which the man reportedly replied, "I wouldn't know, sir. I'm from Alabama.").

That party featured another royal dance, a prelude to Nkrumah's encounter with the queen several years later. Meredith recounts that Nkrumah was warned he would need to dance with the Duchess of Kent, who would be there to represent the Crown. But Nkrumah was ill-trained in Western dance and only felt comfortable with highlife , a West African pop style. It fell to another guest, Louis Armstrong's wife, Lucille, to teach him the foxtrot.

During the country's early years, Nkrumah committed to the socialist sentiments he had first picked up in the U.S. and London, with the belief that a centrally planned economy and state control of cocoa and other valuable industries — what Nkrumah and others took to calling "African socialism" — were essential for the new country to shake the chains of colonialism. This was very concerning to President Kennedy, who in 1962 called Africa "the greatest open field of maneuver in the worldwide competition between the communist bloc and the non-communist." But it was not unique; several other newly-independent African nations, including Kenya, Mali and Tanzania, took guidance from the USSR, which, according to Meredith, "seemed to show that socialism produced rapid modernization."

In The Crown , that embrace is dramatized by a scene in which a portrait of the queen is taken down in the Ghanaian parliament building and replaced with one of Lenin. But although Nkrumah did tour Eastern Europe, his attachment to the USSR was never so extreme, Nuno-Amarteifio recalls.

"Our roots with Russian communism were more intellectual than anything else," he says. "There was nothing visceral about it. Lenin wasn't a personality that we associated with liberty or freedom. If anything, 99 percent of Ghanaians wouldn't have known who Lenin was."

John Parker , an historian at the University of London's School of Oriental and African Studies, agreed that Nkrumah's ties to socialism were mostly ideological and detached from specific foreign policy agreements with the USSR. Still, Nkrumah was seen as a wild card by the U.S. and U.K., and the queen's visit was part of a broader strategy (not an individual impulse, as represented in the show) to corral him and other rogue leaders.

"The British government was certainly concerned to limit Soviet influence in ex-colonies," Parker says. "Overseas tours by the queen were designed broadly to strengthen Commonwealth links."

Meanwhile, African socialism wasn't exactly working the way Ghanaians hoped it would. By the time of the queen's visit in 1961, the economy was crumbling, bribes were routinely collected by government officials at every level of the system (including by Nkrumah himself, who, according to Meredith, even set up a special state-run company to facilitate bribe collection from foreign businessmen) and political opponents were frequently jailed.

"There was a lot of unhappiness, and Nkrumah's position was already delicate," Nuno-Amarteifio says. "If the queen was brave to come to Ghana, he was also brave to welcome her, because it exposed him to tremendous embarrassment should anything happen. The whole world would be watching."

Fortunately, the event seems to have gone off smoothly. As for the dance itself, Nuno-Amarteifio says it barely registered with him and his friends at the time. If anything, he says, The Crown 's depiction of the ecstatic Ghanaian press and bewildered British bureaucrats, shocked that the queen would deign to dance with an African, comes across as paternalistic.

"It was a young white woman dancing with an African," he says. "What do you expect me to do, applaud?"

Did the visit accomplish anything? The big hydroelectric dam referenced in the episode was eventually built, not by the USSR but by an Italian company with financing from the U.S. and U.K. But "Ghana did not 'sever links' with the USSR," Parker says. "To suggest that [the dance] — or the royal tour as a whole — "tipped the balance" of Soviet power in West Africa is untrue."

Nkrumah would remain a proponent of socialism the rest of his life. In 1966, while on a trip to North Korea and China, he was deposed in a military coup that was likely orchestrated by the CIA.

In other words, the episode not only makes much ado out of a forgettable moment but uses that representation to manufacture a victory for the U.S. and U.K. that never really happened. Or, as Nuno-Amarteifio puts it: "I still don't know why that stupid dance is so important."

Tim McDonnell is a journalist covering the environment, conflict and related issues in sub-Saharan Africa. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram .

Copyright 2018 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

NCPR Podcasts

More podcasts from NPR

'the crown' says one dance changed history. the truth isn't so simple.

What the Netflix show gets right — and wrong — about Queen Elizabeth II's visit to Ghana in 1961.

It was a highlight of the latest season of the Netflix series The Crown , which chronicles the early years of Queen Elizabeth II's reign: The year is 1961, the Cold War is heating up and the queen (played by Claire Foy), feeling self-conscious after learning that First Lady Jackie Kennedy (Jodi Balfour) called her "incurious" at a dinner party, decides to take a more proactive role in dealing with Ghana, a former colony whose new leader, Kwame Nkrumah (Danny Sapani), appears to be getting too cozy with the Soviets.

Her solution: A dance with Nkrumah at a ball in the capital, Accra. The foxtrot, specifically, to the extreme, hilarious consternation of Prime Minister Harold Macmillan (Anton Lesser).

It's a high-stakes political gamble that could decide the balance of Soviet power in Africa, which in the early 1960s was fast emerging as a Cold War battleground. To everyone's relief, the dance is a success. The implication is that, in exchange for his photo op dancing with the queen, Nkrumah will "come back to the fold" and squash Soviet hopes for Africa. Later, JFK (Michael Hall) crows to Jackie that her jab at the queen precipitated a major foreign policy victory for the U.S. and U.K. It's the foxtrot that changes the course of history.

"Well, that's nice," says Nat Nuno-Amarteifio , an architect and amateur historian who served as mayor of Accra from 1994-98 and remembers the queen's supposedly fateful visit from when he was a teenage student. "It's a lot of bulls**t."

It turns out The Crown got a lot wrong about that dance, according to Nuno-Amarteifio and other Ghanaian history experts.

There's no dispute that the Ghana visit happened, or that Nkrumah and the queen shared a dance, as shown in the photo above. But the dance wasn't exactly a pivotal moment for Nkrumah's political philosophy, which continued to adhere to socialism in subsequent years, even earning him the Lenin Peace Prize the year after the queen's visit.

"I'm surprised that the dance has attained this retroactive reputation," Nuno-Amarteifio says. "Nobody talked about it then."

At the time, Nkrumah was likely Africa's most influential leader. As a young man in the mid-1930s, he had scraped together enough cash from his farming family in what was then the British colony of Gold Coast to travel to the U.S. for an education. He worked his way through philosophy and theology degrees at Lincoln College and the University of Pennsylvania, followed by two years in London forming alliances with other anti-colonial organizers who were poised to dislodge Britain, France and other colonial powers from their seats in Africa. In 1947, when a pro-independence party began to gather momentum in Accra, its members recruited Nkrumah as their leader. He returned to Gold Coast, but soon found himself imprisoned in a converted British beach fort after a strike he helped organize turned violent. Still, at the next election in 1951, he ran for office from his cell and won a seat in Parliament. As his party's leader, he was installed as prime minister, and the British had no choice but to release him.

Over the next several years he helped coax the country toward independence, under the watchful eye of a British governor. During that time, he nurtured a cult of personality, promoted by newspapers as a kind of towering superhero who would soon vanquish the imperialists who had occupied the country for nearly a century. Sure enough, in 1957 Nkrumah succeeded in passing legislation granting Ghana full self-government, making it the first colony in sub-Saharan Africa after South Africa to gain independence. The independence celebration in Accra was attended by political leaders from across the globe, including Vice President Richard Nixon (according to historian Martin Meredith's The Fate of Africa , Nixon infamously asked a black guest at the party how it felt to be free, to which the man reportedly replied, "I wouldn't know, sir. I'm from Alabama.").

That party featured another royal dance, a prelude to Nkrumah's encounter with the queen several years later. Meredith recounts that Nkrumah was warned he would need to dance with the Duchess of Kent, who would be there to represent the Crown. But Nkrumah was ill-trained in Western dance and only felt comfortable with highlife , a West African pop style. It fell to another guest, Louis Armstrong's wife, Lucille, to teach him the foxtrot.

During the country's early years, Nkrumah committed to the socialist sentiments he had first picked up in the U.S. and London, with the belief that a centrally planned economy and state control of cocoa and other valuable industries — what Nkrumah and others took to calling "African socialism" — were essential for the new country to shake the chains of colonialism. This was very concerning to President Kennedy, who in 1962 called Africa "the greatest open field of maneuver in the worldwide competition between the communist bloc and the non-communist." But it was not unique; several other newly-independent African nations, including Kenya, Mali and Tanzania, took guidance from the USSR, which, according to Meredith, "seemed to show that socialism produced rapid modernization."

In The Crown , that embrace is dramatized by a scene in which a portrait of the queen is taken down in the Ghanaian parliament building and replaced with one of Lenin. But although Nkrumah did tour Eastern Europe, his attachment to the USSR was never so extreme, Nuno-Amarteifio recalls.

"Our roots with Russian communism were more intellectual than anything else," he says. "There was nothing visceral about it. Lenin wasn't a personality that we associated with liberty or freedom. If anything, 99 percent of Ghanaians wouldn't have known who Lenin was."

John Parker , an historian at the University of London's School of Oriental and African Studies, agreed that Nkrumah's ties to socialism were mostly ideological and detached from specific foreign policy agreements with the USSR. Still, Nkrumah was seen as a wild card by the U.S. and U.K., and the queen's visit was part of a broader strategy (not an individual impulse, as represented in the show) to corral him and other rogue leaders.

"The British government was certainly concerned to limit Soviet influence in ex-colonies," Parker says. "Overseas tours by the queen were designed broadly to strengthen Commonwealth links."

Meanwhile, African socialism wasn't exactly working the way Ghanaians hoped it would. By the time of the queen's visit in 1961, the economy was crumbling, bribes were routinely collected by government officials at every level of the system (including by Nkrumah himself, who, according to Meredith, even set up a special state-run company to facilitate bribe collection from foreign businessmen) and political opponents were frequently jailed.

"There was a lot of unhappiness, and Nkrumah's position was already delicate," Nuno-Amarteifio says. "If the queen was brave to come to Ghana, he was also brave to welcome her, because it exposed him to tremendous embarrassment should anything happen. The whole world would be watching."

Fortunately, the event seems to have gone off smoothly. As for the dance itself, Nuno-Amarteifio says it barely registered with him and his friends at the time. If anything, he says, The Crown 's depiction of the ecstatic Ghanaian press and bewildered British bureaucrats, shocked that the queen would deign to dance with an African, comes across as paternalistic.

"It was a young white woman dancing with an African," he says. "What do you expect me to do, applaud?"

Did the visit accomplish anything? The big hydroelectric dam referenced in the episode was eventually built, not by the USSR but by an Italian company with financing from the U.S. and U.K. But "Ghana did not 'sever links' with the USSR," Parker says. "To suggest that [the dance] — or the royal tour as a whole — "tipped the balance" of Soviet power in West Africa is untrue."

Nkrumah would remain a proponent of socialism the rest of his life. In 1966, while on a trip to North Korea and China, he was deposed in a military coup that was likely orchestrated by the CIA.

In other words, the episode not only makes much ado out of a forgettable moment but uses that representation to manufacture a victory for the U.S. and U.K. that never really happened. Or, as Nuno-Amarteifio puts it: "I still don't know why that stupid dance is so important."

More from NPR

Hamas releases video of a second american being held hostage in gaza, trump vp contender kristi noem responds to backlash over story about killing her dog, both sides prepare as florida's six-week abortion ban is set to take effect wednesday, bernie sanders says netanyahu is attacking campus protests to deflect war criticism, hamas says it's preparing to respond to israel's latest gaza cease-fire proposal, a 100-degree heat wave in gaza offers a sweltering glimpse of a tough summer to come, a student club is suing its school, saying its pro-palestinian views were censored, an afghan migrant, age 17, drowned in a bosnian river. here's how citizens responded, got brothers or sisters warm sibling bonds help boost happiness as you age, what abortion politics has to do with new rights for pregnant workers, iran women's protests are the focus of 'persepolis' author marjane satrapi's new book, mike johnson and the troubled history of recent republican speakers.

Watch: Queen Elizabeth II's 1961 visit to Ghana

Queen Elizabeth II inspects men of the newly-renamed Queen's Own Nigeria Regiment, Royal West African Frontier Force, at Kaduna Airport, Nigeria, during her Commonwealth Tour, 2nd February 1956. (Photo by Fox Photos/Hulton Archive/Getty Images) Image: Getty Images

The year was 1961, and Queen Elizabeth II was establishing a reputation for herself as a real jet setter. Watch this British Pathé footage of the Queen in Ghana, West Africa.

In 1961, Queen Elizabeth visited several countries around the world, but perhaps what was most notable was her very first trip to Ghana, a country in West Africa. The young Queen showed during this trip that while the Royal's family's powers were limited the monarchy could still have an impact.

Ghana is a former British colony that gained its independence in 1957. British members of Parliament and the public did not want the Queen to take the trip due to rising tensions in a country where President Kwame Nkrumah was well on his way to becoming a dictator.

Five days before Elizabeth's trip was to begin, bombs went off in the capital city of Accra. A statue of Nkrumah was hit, which showed the president was a target.

The Queen was not deterred. One reason she was reluctant to reschedule was that he had previously canceled in 1959 when she was pregnant with Prince Andrew. As the head of the Commonwealth, the Queen did not want to insult Ghana by postponing the visit.

The other reason being that the Queen was aware Nkrumah was getting closer to the Soviet Union, which wanted to expand its foothold in Africa amidst the Cold War. The Ghanaian leader had even traveled to Moscow that October.

At one point Queen Elizabeth declared "How silly I should look if I was scared to visit Ghana and then [Soviet leader Nikita] Khrushchev went and had a good reception."

She also told the Prime Minister "I am not a film star. I am the head of the Commonwealth — and I am paid to face any risks that may be involved. Nor do I say this lightly. Do not forget that I have three children."

However, the Queen's trip went well. HRH Elizabeth was met by President Kwame Nkrumah in Accra, the nation's capital. Huge crowds gathered to greet Queen Elizabeth as she met with dignitaries and several government ministers.

Have a look at the footage below, courtesy of British Pathe

- WATCH: Queen Elizabeth Attends The Opera

- Princess Anne's christening

* Originally published in March 2020. Updated in 2022.

BHT newsletter

You may also like.

- Most Recent

Is this the last-known footage o...

On this day in 1819, Queen Victoria was born. This footage of Queen...

The spiritual claims and legends...

Have more spiritual claims and legends attached to Glastonbury than...

Wallis Simpson and the royal tit...

This moment in royal history happened all because Edward VIII abdic...

Why Queen Elizabeth II is in the...

Queen Elizabeth II is a Guinness Book of Records seven times over b...

WATCH: Incredible footage of the...

Have a look at this amazing footage of Queen Elizabeth addressing W...

Princess Diana was criticized fo...

Princess Diana was criticized for her "ignorance" of Northern Irela...

What the Royal Family’s favourit...

How much do you know about what the Royal Family drinks?

The Royal Family members who hav...

From Princess Anne to Captain Mark Phillips, did you know that seve...

A history of London Zoo, the wor...

The Zoological Society of London opened a zoological garden in Rege...

Prince William's favorite...How ...

Here's how to make one of Prince William's favorite dishes.

Global site navigation

- Celebrity biographies

- Messages - Wishes - Quotes

- TV-shows and movies

- Bizarre facts

- Celebrities

- Family and Relationships

- Real Estate

Queen Elizabeth’s Historic Visits To Ghana In Ten Rare Photos

- Queen Elizabeth visited Ghana twice before her demise on Thursday, September 8, 2022

- She first visited Ghana in 1961 under Nkrumah's presidency and again in 1999 under Jerry John Rawlings

- YEN.com.gh presents some of the rare photos that capture her visits to her former colony

New feature: Check out news exactly for YOU ➡️ find “Recommended for you” block and enjoy!

The late Queen Elizabeth II visited several countries worldwide in 1961; however, the most notable of all her visits was the one to Ghana.

Before she left on the trip, members of the UK Parliament and the public did not want her to go due to rising tensions in Ghana, where Kwame Nkrumah had toppled the colonial government a few years earlier.

The UK Parliament was concerned that her visit could prove too dangerous. But her trip was successful. According to Biography, from the moment Elizabeth arrived in Ghana, along with Prince Philip, she was surrounded by crowds and excitement.

Video captures Fante chiefs giving away massive gold to Queen Elizabeth II in 1961

She would visit Ghana again in 1999 during the 4th Republican administration of late President Jerry John Rawlings .

PAY ATTENTION: Click “See First” under the “Following” tab to see YEN.com.gh News on your News Feed!

YEN.com.gh presents that historic visit to Ghana over six decades ago in ten rare photos.

1. Queen Elizabeth II At Kumasi Sports Stadium

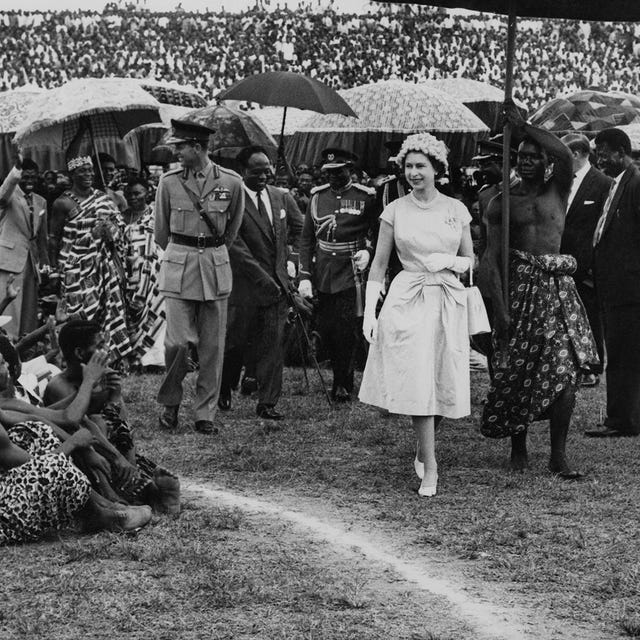

Queen Elizabeth II makes her way underneath a large, gaily colored umbrella, to a dais to watch the Durbar of the Ashanti Chiefs, at Kumasi Sports Stadium, now Baba Yara Stadium.

Here, the late Queen wears a bright yellow outfit, demonstrating that she's always had strong sense for fashion.

Queen Elizabeth II With Kwame Nkrumah

Here Ghana's president in the first Republic, Kwame Nkrumah, and Queen Elizabeth II attend a Diplomatic Corps reception in Accra on November 11, 1961.

Akufo-Addo, Bawumia, other Ghanaians share touching tributes after Queen Elizabeth II died

The Queen's 1961 visit to Ghana was strategic amid Nkrumah's love-affair with the then Soviet Union.

Queen Elizabeth II Ride With Nkrumah During 1961 Visit

Queen Elizabeth II and President Kwame Nkrumah rode in an open-top limousine through cheering crowds in Accra, during the Royal tour of Ghana in 1961.

The Queen's visit was highly successful, contrary to concerns that it could prove dangerous for her.

Queen Elizabeth II Visits A Ghanaian Market

Queen Elizabeth II with President Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana (in dark brown suit) greeting crowds in the marketplace of Accra during the Royal tour of Ghana in 1961.

Her visit to Ghana was seen as a confirmation of Nkrumah's stewardship of the new West African country that had won independence from British rule.

Queen Elizabeth Dances With Nkrumah

Queen Elizabeth II is seen here dancing with Ghana's first republican president, president Kwame Nkrumah on November 20, 1961, at a farewell ball held at State House, Accra.

Westminster Abbey's role in Queen Elizabeth II's life

They, and the Duke of Edinburgh, danced to a version of 'High Life' composed specially for the occasion and entitled 'Welcome Your Majesty'.

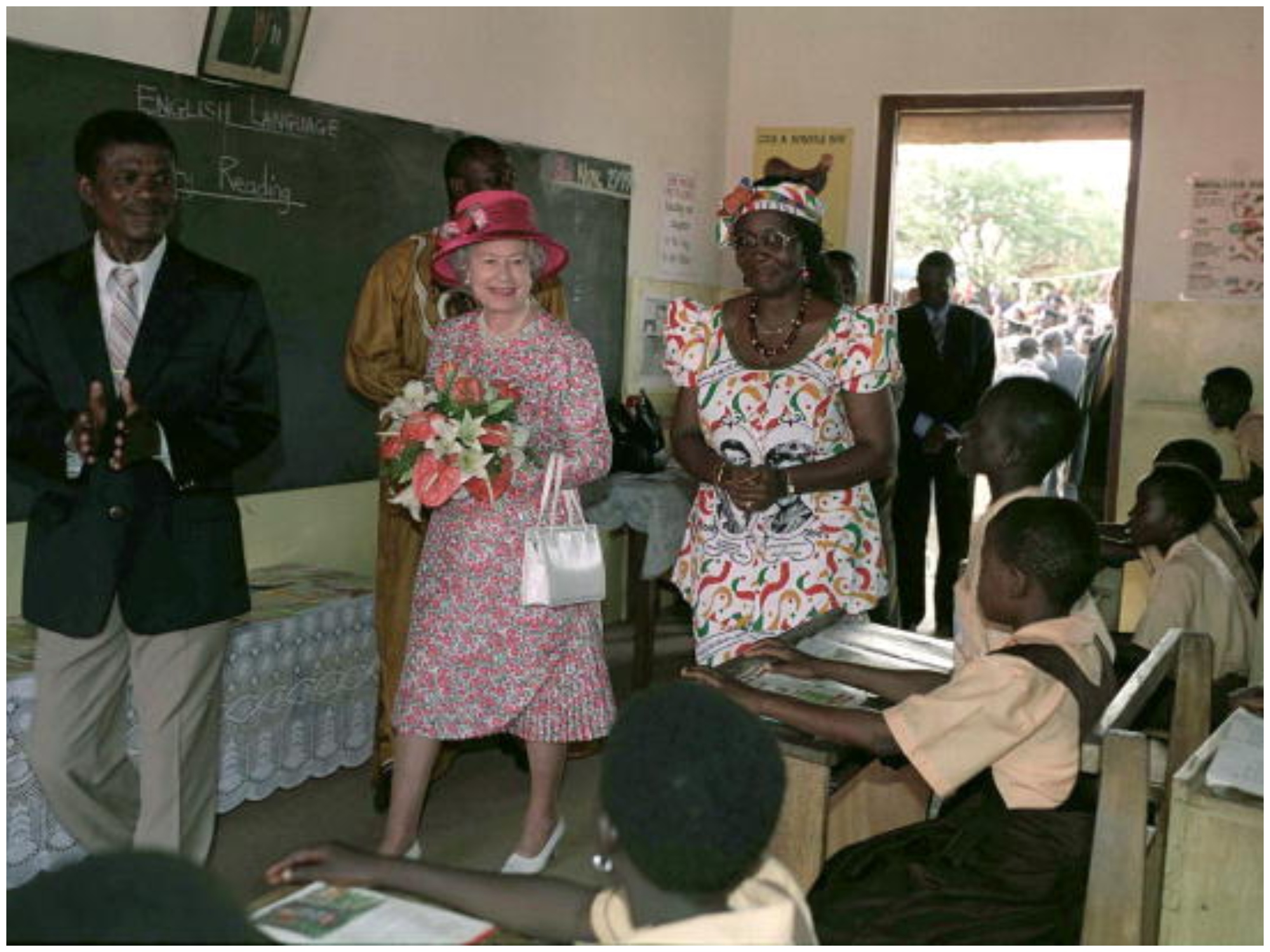

Queen Elizabeth II Visits Wireless Cluster Junior School

On November 8, 1999, the Queen visited the Wireless Cluster Junior School in Accra during her second visit to Ghana under late President Jerry John Rawlings. The public school was established by the erstwhile British colonial government.

The woman sitting next to her is wearing a dress made of fabric printed with the Queen's portrait and President Rawlings.

Ghana Students Hold Up Portrait Of Queen Elizabeth II

School children hold up a portrait of Queen Elizabeth II upon her arrival in Accra during her two-day visit to Ghana in 1999.

She told Parliament during that visit that the United Kingdom is Ghana’s most significant trading partner and best export customer. She said British investment in Ghana far surpasses that of any other industrialised country.

From Victoria to Elizabeth II: The myth about late Queen's throne in Nigeria

Queen Elizabeth II at a classroom of Wireless Cluster Junior School

The Queen visited a classroom during her tour of the Wireless Cluster Junior School in Accra during her 1999 visit.

She applauded the work of Ghana’s achievements in Parliament and said she was confident of a successful future for the two countries in the march towards the 21st century.

Queen Elizabeth II Chats With Rawlings During Her 1999 Visit

Queen Elizabeth II and Ghanaian President Jerry Rawlings walk together upon the Queen's arrival for a state visit to the former British colony on November 7, 1999.

She commended Rawlings and Parliament for ensuring free media, a truly independent judiciary and a democratically chosen, accountable executive that will provide the conditions under which the equality of opportunity, initiative and a stable society can flourish.

Queen Elizabeth II And Rawlings Wave Shortly After She Addressed Ghana's Parliament

Britain's Queen Elizabeth II and Rawlings wave to the crowd gathered on November 8, 1999 outside the parliament in Accra on the second day of the monarch's two-day visit to Ghana.

Queen Elizabeth II: How she spent her time in Nigeria, photos drop

She had just concluded a speech to Parliament where she underscored the importance of Ghana to the United Kingdom in terms of trade and business.

Queen Elizabeth II: Five Things That Will Happen Now That Longest Serving British Monarch Has Died

Before her death was announced, the world had been on edge after the Royal Palace announced that Queen Elizabeth II was under medical supervision in Scotland.

Many also said the official statement from Buckingham Palace, which disclosed that doctors were concerned for her health and had "recommended she remain under medical supervision," showed her grave condition. However, Buckingham Palace has announced the Queen died peacefully in her sleep Thursday afternoon at Balmoral, her castle in Scotland.

YEN.com.gh presents the five things that would happen now that Queen Elizabeth II passed on.

New feature: Check out news exactly for YOU ➡️ find "Recommended for you" block and enjoy!

Source: YEN.com.gh

- The Inventory

Support Quartz

Fund next-gen business journalism with $10 a month

Free Newsletters

Netflix’s The Crown got a lot wrong about the Queen’s visit to Ghana and Nkrumah

“The Crown” on Netflix is a show about the life of Queen Elizabeth II, rich with period detail. Rich, that is, until the first scene in episode eight of the second season, which opens in an ersatz orientalist fantasy palace that’s supposed to be in Accra, Ghana.

Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah (played ably by British actor Danny Sapani—at least until the soul-curdling moment he tries to speak Twi) stands at a podium talking about forging new alliances among African states. A confederation of African stereotypes looks on approvingly.

It’s crosscut with a scene where soldiers take down a portrait of the Queen. As president Nkrumah screams about “a socialist Africa for Africans,” the soldiers put up a portrait of Lenin.

In the episode “Dear Mrs. Kennedy,” Queen Elizabeth, played by Claire Foy, wades into a standoff between the US and Russia over Nkrumah’s “precious dam,” to stop Russia “turn[ing] the whole continent red.” (You can take a moment to appreciate the irony) .

Elizabeth mostly wants to prove to Jackie Kennedy that the Queen is not irrelevant. There’s some vague stuff about Britain losing its place in the world, and the Queen establishing herself as the head of the Commonwealth. But mostly, it’s because US president John F Kennedy’s hot wife said she had thick ankles.

Let’s be clear, because it seems like the show’s writers may not have been aware of the following. The British did not build any orientalist fantasy palaces in Accra. Nkrumah was a measured orator, (I’ll leave you to decide why the show runners made him an angry black man.) And Ghana was never an African satellite state of the Soviet Union.

Importantly, Nkrumah’s “precious dam” still provides much of Ghana’s electricity. Surplus power from the Akosombo Dam is exported to other west African countries. Back when it was built, in the mid-1960s, they had almost no power plants of their own, because there was virtually no spending on infrastructure during the colonial era. Which is one of the reasons African countries courting communist Russia in the first place.

Clearly, we should know better than to trust a Netflix show with the nuances of post-colonial Africa, especially after that Idris Elba movie about a generic horrific African war as if they’re interchangeable and we all have one.

In ‘The Crown,” the Queen visits Ghana in 1961. She dances with Nkrumah, (it’s controversial, because he’s an African! And it’s the foxtrot! How racy!) The president is “awed by the gesture,” a newsreel intones, and suspends all contact with the Russians.

Except Nkrumah did not. The Queen did visit, and spent 11 days in the country. But Ghana’s president was adept at playing the British and Americans against the Russians to get what he wanted. As much as Elizabeth thought she was charming and gaming Kwame, Kwame was charming and gaming Elizabeth.

By the time 1961 rolled around, Ghana had been independent for four years.

Kwame Nkrumah first led independence protests in the late 1940s and got a three-year sentence for economic sabotage and subversive activities. In 1951, while still in prison, he stood for election as head of the Convention People’s Party, which won all but four of Ghana’s 38 seats. Nkrumah was released from jail and became head of government business later that day under colonial governor Charles Arden-Clarke. Nkrumah declared: “I am no communist, and never have been.”

But at heart, Nkrumah was always a socialist. He wrote extensively about moving Ghana closer to states he thought best represented the interests of pan-Africanism and away from the countries that stood to lose wealth and influence if his vision of African unity was realized.

This is where the Soviet Union came in. By the time Ghana won independence and Nkrumah became prime minister in 1957, most of Ghana’s trade was still controlled by foreign firms: over 90% of all importers, and 96% of all timber concessions were run by western firms. If Nkrumah was going to change this, he needed a bargaining chip.

In 1956, during the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Nikita Khrushchev recognized “the awakening of the African people.” And Nkrumah’s administration would come to capitalize on that, negotiating loans with the Soviet Union on better terms than the British and International Monetary Fund offered, along with industrial plants and trade agreements.

Nkrumah became Ghana’s first president in 1960 wasn’t just “wily” like a “lion” as Prince Phillip (played by Matt Smith) says in a bit of casual racism (that is literally the most believable thing in this episode.) Nkrumah was skilled at playing east against west, and telling each side what they wanted to hear to get what he wanted.

In fact, Russia stayed influential long after the Queen’s visit, and only really backed out of Ghana in 1966 after eight Russian advisors were killed in the coup d’état that deposed Nkrumah. Even then, relations with the Soviet Union ebbed and flowed with different Ghanaian governments.

I was born in Moscow in 1985 to Ghanaian parents. My mother was attending a Russian medical school named after Congolese prime minister Patrice Lumumba, who was assassinated in 1961 by the Americans and Belgians . It used to be that most of the Ghanaian elite were trained in the US or UK. Now it’s the US, UK and the former Soviet States.

The sad thing about this episode of “The Crown” is that it’s the most significant dramatization of the events of 1961 to date. And Ghanaians are depicted as background players in the fate of their own country, which simply isn’t true. This is how people come to believe they have no heroes. This is how people come to believe they are just victims of history.

* Correction: Kwame Nkrumah became prime minister after independence in 1957 and president in 1960.

📬 Sign up for the Daily Brief

Our free, fast, and fun briefing on the global economy, delivered every weekday morning.

'The Crown' Says One Dance Changed History. The Truth Isn't So Simple

It was a highlight of the latest season of the Netflix series The Crown , which chronicles the early years of Queen Elizabeth II's reign: The year is 1961, the Cold War is heating up and the queen (played by Claire Foy), feeling self-conscious after learning that First Lady Jackie Kennedy (Jodi Balfour) called her "incurious" at a dinner party, decides to take a more proactive role in dealing with Ghana, a former colony whose new leader, Kwame Nkrumah (Danny Sapani), appears to be getting too cozy with the Soviets.

Her solution: A dance with Nkrumah at a ball in the capital, Accra. The foxtrot, specifically, to the extreme, hilarious consternation of Prime Minister Harold Macmillan (Anton Lesser).

It's a high-stakes political gamble that could decide the balance of Soviet power in Africa, which in the early 1960s was fast emerging as a Cold War battleground. To everyone's relief, the dance is a success. The implication is that, in exchange for his photo op dancing with the queen, Nkrumah will "come back to the fold" and squash Soviet hopes for Africa. Later, JFK (Michael Hall) crows to Jackie that her jab at the queen precipitated a major foreign policy victory for the U.S. and U.K. It's the foxtrot that changes the course of history.

"Well, that's nice," says Nat Nuno-Amarteifio , an architect and amateur historian who served as mayor of Accra from 1994-98 and remembers the queen's supposedly fateful visit from when he was a teenage student. "It's a lot of bulls**t."

It turns out The Crown got a lot wrong about that dance, according to Nuno-Amarteifio and other Ghanaian history experts.

There's no dispute that the Ghana visit happened, or that Nkrumah and the queen shared a dance, as shown in the photo above. But the dance wasn't exactly a pivotal moment for Nkrumah's political philosophy, which continued to adhere to socialism in subsequent years, even earning him the Lenin Peace Prize the year after the queen's visit.

"I'm surprised that the dance has attained this retroactive reputation," Nuno-Amarteifio says. "Nobody talked about it then."

At the time, Nkrumah was likely Africa's most influential leader. As a young man in the mid-1930s, he had scraped together enough cash from his farming family in what was then the British colony of Gold Coast to travel to the U.S. for an education. He worked his way through philosophy and theology degrees at Lincoln College and the University of Pennsylvania, followed by two years in London forming alliances with other anti-colonial organizers who were poised to dislodge Britain, France and other colonial powers from their seats in Africa. In 1947, when a pro-independence party began to gather momentum in Accra, its members recruited Nkrumah as their leader. He returned to Gold Coast, but soon found himself imprisoned in a converted British beach fort after a strike he helped organize turned violent. Still, at the next election in 1951, he ran for office from his cell and won a seat in Parliament. As his party's leader, he was installed as prime minister, and the British had no choice but to release him.

Over the next several years he helped coax the country toward independence, under the watchful eye of a British governor. During that time, he nurtured a cult of personality, promoted by newspapers as a kind of towering superhero who would soon vanquish the imperialists who had occupied the country for nearly a century. Sure enough, in 1957 Nkrumah succeeded in passing legislation granting Ghana full self-government, making it the first colony in sub-Saharan Africa after South Africa to gain independence. The independence celebration in Accra was attended by political leaders from across the globe, including Vice President Richard Nixon (according to historian Martin Meredith's The Fate of Africa , Nixon infamously asked a black guest at the party how it felt to be free, to which the man reportedly replied, "I wouldn't know, sir. I'm from Alabama.").

That party featured another royal dance, a prelude to Nkrumah's encounter with the queen several years later. Meredith recounts that Nkrumah was warned he would need to dance with the Duchess of Kent, who would be there to represent the Crown. But Nkrumah was ill-trained in Western dance and only felt comfortable with highlife , a West African pop style. It fell to another guest, Louis Armstrong's wife, Lucille, to teach him the foxtrot.

During the country's early years, Nkrumah committed to the socialist sentiments he had first picked up in the U.S. and London, with the belief that a centrally planned economy and state control of cocoa and other valuable industries — what Nkrumah and others took to calling "African socialism" — were essential for the new country to shake the chains of colonialism. This was very concerning to President Kennedy, who in 1962 called Africa "the greatest open field of maneuver in the worldwide competition between the communist bloc and the non-communist." But it was not unique; several other newly-independent African nations, including Kenya, Mali and Tanzania, took guidance from the USSR, which, according to Meredith, "seemed to show that socialism produced rapid modernization."

In The Crown , that embrace is dramatized by a scene in which a portrait of the queen is taken down in the Ghanaian parliament building and replaced with one of Lenin. But although Nkrumah did tour Eastern Europe, his attachment to the USSR was never so extreme, Nuno-Amarteifio recalls.

"Our roots with Russian communism were more intellectual than anything else," he says. "There was nothing visceral about it. Lenin wasn't a personality that we associated with liberty or freedom. If anything, 99 percent of Ghanaians wouldn't have known who Lenin was."

John Parker , an historian at the University of London's School of Oriental and African Studies, agreed that Nkrumah's ties to socialism were mostly ideological and detached from specific foreign policy agreements with the USSR. Still, Nkrumah was seen as a wild card by the U.S. and U.K., and the queen's visit was part of a broader strategy (not an individual impulse, as represented in the show) to corral him and other rogue leaders.

"The British government was certainly concerned to limit Soviet influence in ex-colonies," Parker says. "Overseas tours by the queen were designed broadly to strengthen Commonwealth links."

Meanwhile, African socialism wasn't exactly working the way Ghanaians hoped it would. By the time of the queen's visit in 1961, the economy was crumbling, bribes were routinely collected by government officials at every level of the system (including by Nkrumah himself, who, according to Meredith, even set up a special state-run company to facilitate bribe collection from foreign businessmen) and political opponents were frequently jailed.

"There was a lot of unhappiness, and Nkrumah's position was already delicate," Nuno-Amarteifio says. "If the queen was brave to come to Ghana, he was also brave to welcome her, because it exposed him to tremendous embarrassment should anything happen. The whole world would be watching."

Fortunately, the event seems to have gone off smoothly. As for the dance itself, Nuno-Amarteifio says it barely registered with him and his friends at the time. If anything, he says, The Crown 's depiction of the ecstatic Ghanaian press and bewildered British bureaucrats, shocked that the queen would deign to dance with an African, comes across as paternalistic.

"It was a young white woman dancing with an African," he says. "What do you expect me to do, applaud?"

Did the visit accomplish anything? The big hydroelectric dam referenced in the episode was eventually built, not by the USSR but by an Italian company with financing from the U.S. and U.K. But "Ghana did not 'sever links' with the USSR," Parker says. "To suggest that [the dance] — or the royal tour as a whole — "tipped the balance" of Soviet power in West Africa is untrue."

Nkrumah would remain a proponent of socialism the rest of his life. In 1966, while on a trip to North Korea and China, he was deposed in a military coup that was likely orchestrated by the CIA.

In other words, the episode not only makes much ado out of a forgettable moment but uses that representation to manufacture a victory for the U.S. and U.K. that never really happened. Or, as Nuno-Amarteifio puts it: "I still don't know why that stupid dance is so important."

Tim McDonnell is a journalist covering the environment, conflict and related issues in sub-Saharan Africa. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram .

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

By the time of the queen's visit in 1961, the economy was crumbling, bribes were routinely collected by government officials at every level of the system (including by Nkrumah himself, who ...

Queen Elizabeth II watches a dance performance in an outdoor parade ground, Tamale, Ghana, November 12, 1961; Photo: Paul Schutzer/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images Her visit was a success ...

Shortly after her ascension to the throne, Queen Elizabeth was faced with a fast-changing empire as colonies in Africa gained independence and became republi...

Queen Elizabeth II and President Nkrumah dance the popular Ghana rhythmic shuffle known as the "High Life" at a farewell ball in Accra on Saturday, November 18, 1961. AP. T he Queen danced gaily ...

Queen Elizabeth II's (Claire Foy) visit to Ghana, including a foxtrot dance with President Kwame Nkrumah (Danny Sapani), was more of a diplomatic move to nur...

In Ghana, an iconic dance with Kwame Nkrumah. Of all her tours in Africa, the one at the end of 1961 was among the most crucial, says Meriem Amellal Lalmas, a journalist at FRANCE 24. The Queen ...