Australia - Regulations on Entry, Stay and Residence for PLHIV

Restriction category relative to australia.

- Countries with restrictions for long term stays (>90 days)

HIV-specific entry and residence regulations for Australia

REGULATIONS UPDATE UNAIDS reports that Australia has made reforms to its migration health assessment requirements and procedures, including an annual increase to the “significant cost threshold”, the elimination of the cost assessment related to health services for humanitarian visa applicants and improvement to increase the transparency of the health assessment process. Also, it has been confirmed that a HIV pilot programme for African student visa applicants was officially discontinued in 2011. HIV testing for permanent visa applicants remains in force. People living with HIV are treated similarly to other people with chronic health conditions and disabilities during the country’s immigration health assessment process. Applications for visas from people living with HIV will be assessed against criteria applying to anyone with a chronic health condition. (Source: 3) Editor’s note: Due to the HIV test requirement for permanent visa applicants, we continue to list Australia as a country applying residency restrictions. We will update this page as soon as further information becomes available.

Entry and residence regulations Applicants for visas to visit or migrate to Australia are required to meet certain health requirements. These help ensure that:

- Risks to public health in the Australian community are minimized

- Public expenditure on health and community services is contained

- Australian residents have access to health and other community services in short supply.

Temporary visas Applicants for a temporary visa do not generally need to complete an HIV test. The exceptions apply to temporary visa applicants intending to work or study to become a doctor, dentist, nurse or paramedic. Students (and their dependents) from sub-Saharan Africa who intend to study in Australia for 12 months or more are also tested for HIV. Permanent visas All applicants for a permanent visa must complete an HIV test if they are 15 years or older. Individuals under 15 who may be required to undergo testing are listed here: https://immi.homeaffairs.gov.au/help-support/meeting-our-requirements/health/who-needs-health-examinations If a person is found to be HIV positive, a decision on whether they meet the health requirement for a visa is considered on the same grounds as any other pre-existing medical condition. That is, the disease or condition is not likely to:

- Require healthcare or community services while in Australia

- Result in significant costs to the Australian community

- Prejudice the access of an Australian citizen or permanent resident to healthcare or community services.

A person who initially fails the health requirement, may have it subsequently waived if they are applying for a certain limited number of visa types. The circumstances under which they may have it waived are listed here: https://immi.homeaffairs.gov.au/help-support/meeting-our-requirements/health/who-needs-health-examinations

Up-to-date information, including information on Australia’s temporary and permanent visas, and the health requirements for each, is available at www.immi.gov.au . (Source 1,2) Some HIV/AIDS entry restrictions exist for visitors and foreigners seeking permanent residence in Australia. Depending on the type of visa you apply for, the length of your stay and your intended activities in Australia, you may be required to undergo a medical examination before the Australian Department of Immigration and Border Protection will issue you a visa. If during the course of the application process, you are found to be HIV positive, a decision on the application will be considered on the same grounds as any other pre-existing medical condition (such as tuberculosis or cancer), with the main focus being placed on the cost of the condition to Australia’s healthcare and community services. (Source: 4)

HIV treatment information for Australia

- Albion Street Centre 150 Albion St. Surry Hills 2010 NSW 2010 Australia Phone: 9332 1090 Fax: 9332 4219 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.sesahs.nsw.gov.au/albionstcentre/

- Sydney Sexual Health Service Nightingale Wing 3rd. Floor Sydney Hospital Maquarie St. Sydney 2000 Phone: 9382 7440 Fax: 9382 7475

- AIDS Council of NSW (Acon Sydney) 9 Commonwealth St. Surry Hills P0 Box 350, Darlinghurst 1300 E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 9206 2000

HIV information / HIV NGOs in Australia

Global criminalisation of hiv transmission scan.

- Matthew McMahon, Assistant Director, Health Policy Section, Migration and Visa Policy, Department of Immigration and Citizenship, Belconnen ACT 2617 www.immi.gov.au , January 8, 2010; sent via Asia and Oceania Department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The Netherlands

- Michael Frommer, Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations, PO Box 51 Newtown NSW 2042 / level 1, 222 King Street, Newtown 2042, Australia, www.afao.org.au , by e-mail, August 28, 2014

- UNAIDS; Geneva, press release, July 10, 2014

- US State Department Of State; Bureau of Consular Affairs; https://travel.state.gov / December 17, 2019; consulted June 3, 2021

updated: 6/3/2021 Corrections and additions welcome. Please use the contact us form.

Comments on HIV-restrictions in Australia

Australia’S Hiv Travel Restriction: Progress And Controversies

- Last updated Aug 13, 2023

- Difficulty Intemediate

- Category United States

Australia's HIV travel restrictions have long been a topic of debate and contention. In an era where the discrimination and stigmatization of HIV-positive individuals is diminishing globally, Australia's policy continues to stand out. With purported concerns about public health and healthcare costs, the country imposes strict regulations on travelers with HIV, including mandatory HIV testing, disclosure of HIV status, and possible visa denial for those who test positive. While some argue that these restrictions are necessary to protect the population, others view them as archaic and discriminatory, perpetuating harmful stereotypes about those living with HIV. As the world progresses towards greater inclusivity and acceptance, it begs the question: should Australia re-examine its approach to HIV travel restrictions?

What You'll Learn

What are the current travel restrictions for individuals with hiv entering australia, how do these travel restrictions compare to those in other countries, why does australia have such strict travel restrictions for individuals with hiv, are there any exceptions or waivers available for individuals with hiv who want to travel to australia, have there been any recent efforts to change or relax these travel restrictions in australia.

As of now, individuals with HIV are subject to certain travel restrictions when entering Australia. These restrictions are in place to protect public health and prevent the spread of communicable diseases, including HIV. Here's what you need to know if you have HIV and wish to travel to Australia.

Australia's immigration policy outlines that individuals with HIV are generally considered to have a "significant cost" on the Australian healthcare system. Therefore, it is important to understand the following key points regarding travel restrictions for individuals with HIV entering Australia.

Health examinations:

All individuals, regardless of their HIV status, are required to undergo a medical examination before being granted an Australian visa. The purpose of this examination is to assess the overall health of the applicant and identify any potential health risks, including communicable diseases such as HIV. If HIV is detected during the medical examination, additional evaluations may be required.

Character requirement:

In addition to health examinations, those applying for an Australian visa must also meet the character requirement. This means that individuals with HIV may have their visa application assessed based on their medical condition and potential impact on public health. The Department of Home Affairs will consider factors such as the individual's compliance with treatment, risk of transmitting HIV, and overall health status.

The Health Requirement:

The Health Requirement is a criteria that must be met by all individuals applying for an Australian visa. It mandates that visa applicants should not have a condition that is likely to result in them being a significant burden on the Australian healthcare system, including ongoing medical or hospital costs.

Temporary visas:

Individuals with HIV may still be eligible for temporary visas to enter Australia, provided they meet the health and character requirements. Such visas include tourist visas, student visas, and temporary work visas. However, it is essential to note that visa application outcomes may vary based on individual circumstances and the type of visa applied for.

Permanent visas:

Obtaining a permanent visa may be more challenging for individuals with HIV due to the potential burden on the Australian healthcare system. Applicants for permanent visas are subject to more stringent health and character requirements, and the decision is made on a case-by-case basis. It is recommended to seek advice from a migration agent or immigration lawyer to understand the options available in such cases.

It is important to note that the exact travel restrictions for individuals with HIV entering Australia may change over time due to evolving policies and practices. Therefore, it is advisable to consult the official website of the Australian Department of Home Affairs or seek advice from a qualified migration agent for the most up-to-date information and guidance.

An Overview of Travel Restrictions from Germany to the USA: What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to evolve, countries around the world have implemented various travel restrictions to mitigate the spread of the virus. These restrictions range from complete border closures to mandatory quarantine measures for incoming travelers. In this article, we will explore how these travel restrictions compare to those implemented by other countries.

Countries such as Australia and New Zealand have adopted some of the most stringent travel restrictions in the world. Both countries have closed their borders to all incoming travelers, with few exceptions for essential workers and citizens returning home. Additionally, anyone entering these countries must undergo a mandatory 14-day quarantine period at a designated facility. These measures have been effective in keeping the number of COVID-19 cases low but have also resulted in severe disruptions to travel and tourism industries.

In Europe, countries have taken a more varied approach to travel restrictions. Some countries, such as France and Spain, initially closed their borders during the first wave of the pandemic but have since relaxed these measures. They now allow travelers from selected countries to enter with certain restrictions, such as pre-travel testing or quarantine requirements. Other countries, such as Germany and Switzerland, have introduced less stringent measures, such as mandatory testing at the border or self-isolation upon arrival.

In Asia, countries like China and South Korea have implemented strict travel restrictions to control the transmission of the virus. China has temporarily banned most foreign nationals from entering the country, while South Korea requires all incoming travelers to provide proof of a negative COVID-19 test and undergo a quarantine period.

In contrast, some countries have opted for less restrictive travel policies. For example, the United States has not implemented a nationwide travel ban, instead leaving it up to individual states to enforce restrictions. This has resulted in a patchwork of measures across the country, with some states requiring mandatory quarantines for out-of-state visitors and others imposing no restrictions at all.

Overall, the severity of travel restrictions varies greatly from country to country. Some nations have taken a more proactive approach by implementing strict border closures and mandatory quarantines, while others have opted for less stringent measures. The effectiveness of these restrictions in controlling the spread of COVID-19 is still under debate, and it remains to be seen how they will evolve in response to the ongoing pandemic.

New EU Travel Restrictions: What You Need to Know

Australia has implemented strict travel restrictions for individuals with HIV, which has raised questions regarding their reasoning behind such measures. The country's policy has been widely criticized by human rights advocates and medical professionals, who argue that it is discriminatory and outdated.

The travel restrictions were first put in place in the late 1980s, during the height of the global HIV/AIDS epidemic. At that time, there was a lack of understanding about the disease, leading many countries to implement policies that were aimed at preventing its spread. Australia's policy was one of the most severe, requiring individuals with HIV to obtain special permission from the government before entering the country.

The rationale behind these restrictions was based on two main concerns. The first was the fear that people with HIV would become a burden on the Australian healthcare system. This was partly due to the perception that HIV/AIDS was a deadly and incurable disease at the time. The second concern was the belief that people with HIV were a risk to public health and that they could potentially transmit the virus to others.

However, as medical knowledge and treatments for HIV have advanced over the years, so too has our understanding of the virus. Today, HIV is a manageable chronic condition, thanks to highly effective antiretroviral therapy (ART). People living with HIV who are on treatment and have an undetectable viral load are not infectious and cannot transmit the virus to others.

Many countries have recognized this scientific evidence and have relaxed or completely abolished their travel restrictions for people with HIV. For example, in 2010, the United States lifted its 22-year ban on HIV-positive travelers entering the country. The decision was based on scientific evidence that showed HIV-positive individuals who are on treatment and have an undetectable viral load pose no risk to public health.

Despite this, Australia has been slow to change its policy. Human rights organizations and medical professionals have called for the country to follow the lead of other nations and revise its travel restrictions. They argue that the current policies discriminate against people living with HIV, violate their human rights, and stigmatize them based on outdated and incorrect information.

In recent years, there have been some positive developments in this area. In 2019, the Australian government announced that it would review the country's migration laws regarding people with HIV. The review aims to determine whether the current policy aligns with current scientific evidence and international human rights standards. The outcome of this review remains to be seen, but it offers hope for a more equitable and evidence-based approach to HIV travel restrictions in Australia.

In conclusion, Australia's strict travel restrictions for individuals with HIV are based on outdated fears and misconceptions about the virus. In light of scientific advancements and international practices, many countries have abandoned or relaxed their HIV travel restrictions. Australia's current policy is discriminatory and stigmatizing, and it is high time for the country to adopt a more progressive and evidence-based approach. The ongoing review of Australia's migration laws offers an opportunity to rectify this situation and ensure equal rights for people living with HIV.

Current Travel Restrictions: What You Need to Know Today

If you have HIV and are interested in traveling to Australia, you may be wondering if there are any exceptions or waivers available to allow you entry into the country. The good news is that Australia does not have a specific entry ban for individuals with HIV. However, there are some requirements and considerations you should be aware of.

Medical Examination:

All individuals who are planning to stay in Australia for more than three months are required to undergo a medical examination. This examination includes a chest x-ray and a test for HIV. The purpose of the medical examination is to ensure that you are free from any health conditions that could be a threat to the Australian community or put a strain on the country's healthcare system. The results of your HIV test will be kept confidential and will not be used to deny your entry into Australia.

Healthcare Costs:

Another important consideration for individuals with HIV who want to travel to Australia is healthcare costs. While Australia has a high-quality healthcare system, it can be expensive for non-residents. It is important to have travel insurance that covers pre-existing medical conditions, including HIV, to avoid any financial burden.

Medication:

If you are taking antiretroviral medication for HIV, it is crucial to ensure that you have an adequate supply of medication for the duration of your stay in Australia. It is recommended to carry a copy of your prescription with you, along with a letter from your doctor explaining the purpose of the medication and the dosage instructions.

Visa Requirements:

Apart from the medical examination, individuals with HIV must also meet the regular visa requirements to enter Australia. This may include having a valid passport, demonstrating sufficient funds to support yourself during your stay, and having a clear criminal record. It is important to check the specific visa requirements for your country of citizenship before making any travel plans.

Overall, while there are no specific entry bans for individuals with HIV traveling to Australia, it is important to be aware of the medical examination requirements and healthcare costs. By ensuring that you meet these requirements and plan accordingly, you can have a smooth and enjoyable trip to Australia.

Exploring Miami during COVID-19: Are There Any Travel Restrictions in Place?

In response to the global COVID-19 pandemic, Australia implemented strict travel restrictions to prevent the spread of the virus. These restrictions included a ban on international travel and mandatory quarantine for returning citizens and residents. However, as the situation is continuously evolving and the vaccination rollout progresses, there have been recent efforts to change and relax these travel restrictions in Australia.

One of the major changes to the travel restrictions is the establishment of travel bubbles or travel corridors with certain countries. These bubbles allow for quarantine-free travel between participating countries, as long as travelers meet certain eligibility criteria. For example, Australia has established a travel bubble with New Zealand, allowing residents of both countries to travel between them without having to quarantine upon arrival. This has been a significant development, as it marks the first quarantine-free travel arrangement for Australians since the pandemic began.

Additionally, Australia has recently announced plans to gradually reopen its borders to international tourism. The government has set a target of fully reopening the international border by mid-2022, depending on the country's vaccination rates and the global situation. This indicates a shift in the government's approach from strict travel restrictions to a more measured and phased reopening, taking into consideration the public health risks and the need to revive the tourism industry.

In order to facilitate this reopening, the Australian government has been working on implementing a digital travel pass or vaccine passport system. This system would allow vaccinated individuals to prove their vaccination status and travel eligibility easily and securely. The digital travel pass would provide a convenient and efficient way to verify a person's vaccination status, reducing the need for lengthy quarantine periods. This would not only streamline the travel process but also incentivize vaccination among the population.

Furthermore, there have also been discussions about the possibility of relaxing quarantine requirements for fully vaccinated individuals. This could involve shortening or eliminating quarantine periods for those who have received the full dose of an approved COVID-19 vaccine. This approach recognizes that vaccinated individuals have a reduced risk of transmitting the virus and therefore should be subject to less stringent travel restrictions.

While there have been these recent efforts to change and relax travel restrictions in Australia, it is important to note that the situation remains fluid and subject to change. The government will continue to monitor the global and domestic COVID-19 situation and adjust travel restrictions accordingly. It is essential for travelers to stay updated with the latest travel advice and guidelines provided by the Australian government and health authorities before planning any trips.

The Essential Guide to Airport Travel Rules and Restrictions

Frequently asked questions.

Yes, there are travel restrictions for individuals with HIV who wish to visit Australia. As of 2021, Australia still has regulations in place that require individuals with HIV to declare their condition when applying for a visa.

Australia's HIV travel restriction affects individuals with HIV by requiring them to disclose their HIV status when applying for a visa. This can potentially result in their visa application being denied or additional requirements being imposed on them.

Yes, there are exceptions to Australia's HIV travel restriction. Individuals with HIV can apply for a waiver of the restriction, which is granted on a case-by-case basis. The waiver application process involves providing medical information and demonstrating that the individual poses no risk to public health.

- Melissa Carey Author Reviewer Traveller

- Duke Trotter Author Editor Reviewer Traveller

It is awesome. Thank you for your feedback!

We are sorry. Plesae let us know what went wrong?

We will update our content. Thank you for your feedback!

Leave a comment

United states photos, related posts.

12 Fun Things to Do in Alachua, Florida

- May 07, 2023

Germany Lifts Travel Restrictions to Canary Islands; Allows Tourists to Resume Travel

- Sep 07, 2023

Exploring the Hidden Gem: Top Things to Do in North Ogden

- Jul 07, 2023

12 Romantic Things to Do in a Cozy Cabin

- May 28, 2023

Scotland's Evolving Travel Restrictions: What You Need to Know

- Sep 17, 2023

Navigating Idyllwild: Current Travel Restrictions and Updates

- Sep 12, 2023

HIV-related travel restrictions

- Press release

- Personal stories

- Infographic

Time for Australia to drop visa restrictions for migrants living with HIV, advocates say

Topic: Health

Australia is one of only around 40 countries that still has visa restrictions for people living with HIV. ( ABC News: Canva )

Debbie* will never forget the moment she was diagnosed with HIV.

Key points:

- HIV advocates are urging the government to unwind rules imposing visa restrictions on people living with the condition

- The government concedes Australia's migration health requirements do "not meet community expectations"

- Australia is one of the last 40 or so countries with visa restrictions for people living with HIV

It was 2011, two years after she and her husband had moved to Australia as skilled migrants from Papua New Guinea.

The mother of four was lying in a Queensland hospital bed and doctors were trying to figure out why she was feeling so unwell. That's when they ran blood tests.

The one for human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV, came back positive.

"It was overwhelming," Debbie said.

"It was very hard for me to understand and accept that I had this."

Debbie's husband was then screened and he also tested positive.

Looking back, she is thankful for the support from doctors, nurses and counsellors, who helped her realise HIV was no longer a death sentence, so long as it's managed through medications.

After their diagnoses, Debbie and her husband went on to build a successful business that allowed them to put all four of their children through private school and university.

When they applied for permanent residency (PR) in January 2016 they were shocked to discover their application wouldn't be easy due to their HIV status.

"It was very stressful," Debbie said.

"I had mental health issues like depression, stress and anxiety. I wasn't in a good place."

What are the visa rules for HIV?

Australia is one of only around 40 countries with visa restrictions for people living with HIV.

The United States scrapped its restrictions about a decade ago. The United Kingdom and New Zealand have also dropped theirs.

Australia was criticised in 2021 by the United Nations-affiliated group UNAIDS for having laws that "discriminate against people on the basis of their HIV status".

"The Australian government should wipe away all of the barriers that stop people (with) HIV moving freely to and from Australia," Health Equity Matters CEO Darryl O'Donnell said.

Advocates will use the International AIDS Society's annual conference, being hosted in Brisbane this week, to call on the government to unwind those laws.

They will argue the policy instils stigma and that Australia will struggle to eradicate transmission of the virus without change.

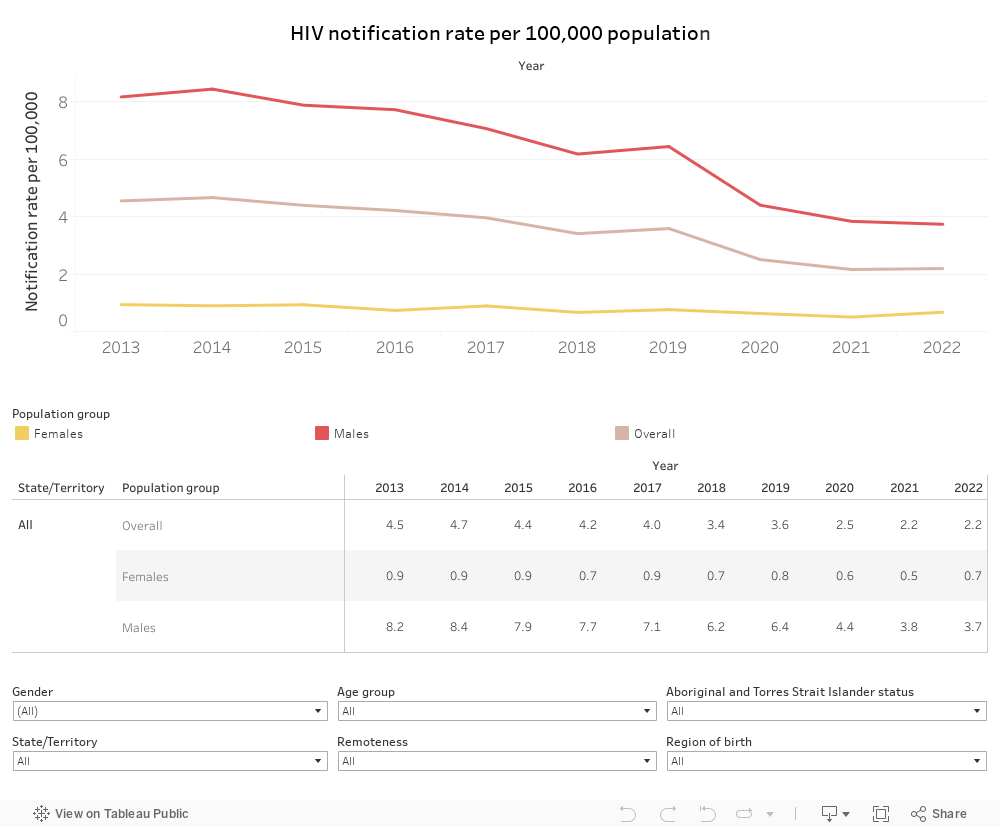

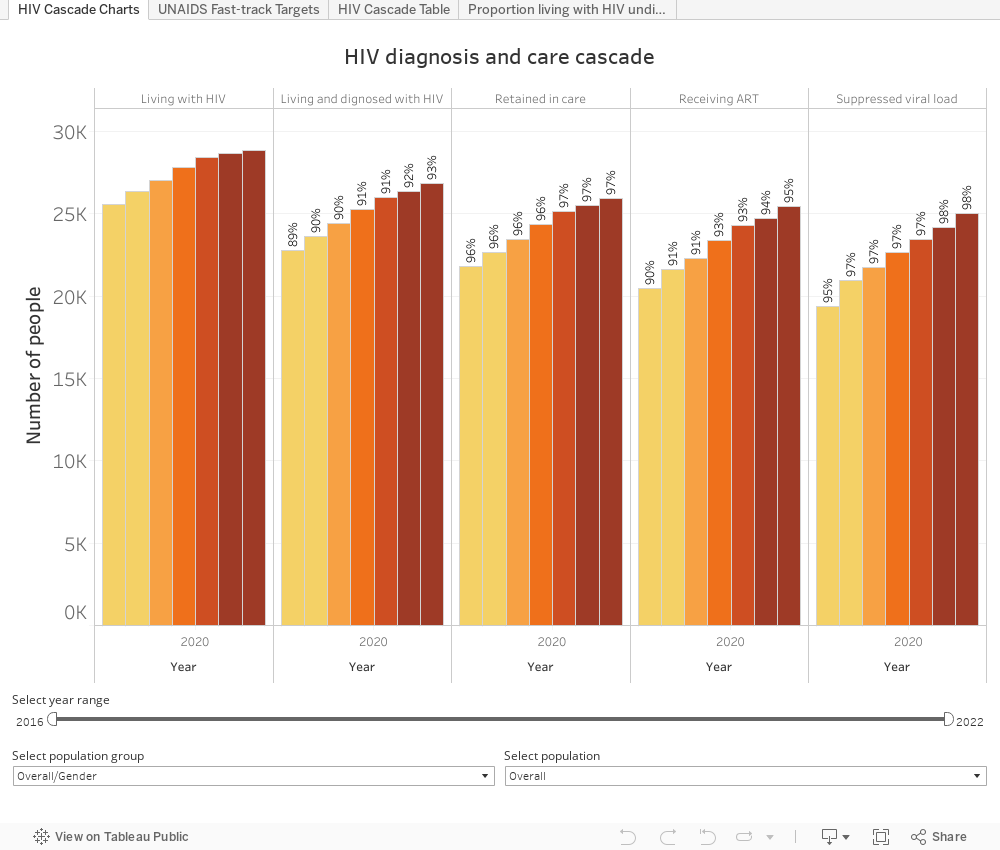

HIV diagnosis in Australia has halved in the past decade and the country could be transmission-free in three-to-five years, according to data from UNSW's Kirby Institute, released last week.

But for that to happen, more work is needed in migrant communities where testing rates are typically low and transmission rates aren't falling as hoped.

Mr O'Donnell said, despite the fact people wanting to remain in Australia permanently will need to be tested eventually, the visa restrictions ingrain stigma and scare people out of testing early.

"If there's fear that a HIV positive test result will become a flag for an application for residency, people will hold back."

For those who are positive, a cost analysis is done to determine if the person will exceed the government's "significant cost threshold".

"The cost of antiretrovirals (the medicines used to fight HIV) are around $11,000 per year," said Alexandra Stratigos, the principal solicitor of the HIV/AIDS Legal Centre.

That's about double the government's cost threshold, she said — meaning everyone with HIV exceeds it.

Those on eligible visas who then apply for PR may be able to get around the policy if they're granted a health waiver.

However, approval of that waiver is discretionary, and people can go to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) — a body that reviews government decisions — to appeal.

Ms Stratigos represents clients at the AAT and said her results proved the policies were outdated.

"We have a relatively high success rate of getting people a permanent visa in the end. But it takes many years of processing," she said.

Ms Stratigos said the existing rules force some applicants to reveal their HIV status to their employer, raising privacy issues, and they can lead to people staying in abusive or exploitative situations because they want to avoid testing.

Rules 'don't meet community expectations'

In most other areas, Australia's response to HIV and AIDS has been world-leading, advocates say.

Collaboration between health officials and at-risk communities has been key to success, underpinned by high testing rates and a focus on prevention and treatment.

It's got Australia on track to potentially be the first country in the world to virtually eliminate community transmission of HIV.

But, Mr O'Donnell said, our immigration policy "hasn't kept up with the advances in science".

"This is an anachronism. It's a throwback to two decades past when we didn't have good treatment for HIV," he said.

"We now have medicines that are very affordable and very cheap. There really isn't an economic impost for someone coming to Australia because of HIV... but people are still locked into a process of seeking residency that can drag on for years and years."

In a statement, Immigration Minister Andrew Giles agreed the health-related visa rules were problematic.

"Australia's approach to migration health requirements does not meet community expectations," he said.

Immigration Minister Andrew Giles says our visa health requirements could be improved. ( ABC News: Adam Kennedy )

"I see this almost every week in the personal decisions I make to intervene in the visa system via ministerial intervention."

Mr Giles said he has "engaged on the issue" with Health Minister Mark Butler, as well as HIV experts and those with lived experience since taking the immigration portfolio.

Debbie's fight for her PR visa stretched on for seven years. She got it earlier this year after an AAT ruling.

"We were not a burden to society. We were trying to prove that and we did," she said.

*Name changed to protect privacy

- Free Condom Resources

HIV and disclosure

Disclosure of your HIV status can cause anxiety. Although you may feel pressured, it is good to know the facts before jumping in and disclosing in situations where it is unnecessary.

Telling your healthcare providers

You are not legally required to disclose your HIV status to any healthcare provider if you don’t want to. This includes medical examinations, surgery and dentistry.

However, it may be wise to disclose since HIV medications may interact with other medications; or the progression or treatment of other conditions may be affected by HIV infection. Under such circumstances, failure to disclose may lead to serious consequences for your health.

Your treatment for other conditions may have to be modified to allow for the effects of HIV infection and HIV medications, and your doctor or dentist can only do this if they are fully informed.

Discuss with your regular HIV specialist whether disclosure to another practitioner is medically necessary.

Disclosing HIV status at work

Generally, you are not required to tell an employer or prospective employer that you are HIV-positive. Check out the exceptions on our HIV and employment page .

While you might need to disclose your status, you still have a duty to ensure your own safety and health, and to avoid affecting the health and safety of others in the work place.

Maintaining an undetectable viral load is one step in reducing risk. If there are accidents at work then there is a significantly reduced risk of transmission.

HIV and travel

You are subject to the local laws of the country that you are visiting, therefore it’s important to have some knowledge of local legislation with regards to HIV disclosure when travelling.

Before you plan your trip, research the country’s laws on having HIV, visas and whether you will face issues bringing medication with you.

It is illegal for HIV-positive individuals to have sex without documenting disclosure in some jurisdictions and some people living with HIV have been prosecuted without onward transmission occurring.

HIV disclosure and intimate relationships

A common concern for many people with HIV is around the disclosure of their status in an intimate relationship. It brings up questions like: When is the right time? How should I do it? Should I even disclose?

The discrimination and stigma towards people with HIV, largely driven by ignorance and lack of knowledge, is still pervasive and can cause significant anxiety around disclosure. There is a lot of justified fear and consideration about how someone will react when they find out your status.

Should you disclose? Do you have to disclose?

Under Australian law, you do not have to disclose your positive status to a sexual partner on the proviso that you “take reasonable precautions to prevent HIV transmission”.

This means that if someone has HIV and they have sex with someone, they are not legally required to disclose this information so long as they are taking steps to protect the other person.

So what constitutes a reasonable precaution? A precaution could be:

- Using a condom,

- Having an undetectable viral load .

- Seeking and getting confirmation that the other person is using PrEP .

- A combination of the above

The bonus with a condom is that it also prevents other STIs like syphilis, which we are still experiencing an outbreak of syphilis .

One of the risks with using the knowledge that the other person is using PrEP is the possibility that they are not telling the truth. If you have sex with someone who says they are using PrEP but actually aren’t, you could be at risk from a legal standpoint.

It’s also important to remember that even if you disclose your status, you are still legally required to take reasonable precautions to prevent transmission. Disclosure does not allow for sex without some form of protection.

When should you disclose?

Contrary to what you might think, there is no wrong or right time to say those words “I’m HIV positive.” It could be on the first date or one the fiftieth.

You can disclose when it feels right, whatever the circumstances.

To disclose one’s HIV status can be a highly complex topic. We believe no one should be pressured into making that choice, though unfortunately “pressured” is how a lot of people often find themselves. This pressure can be both external and internal.

Whatever the case, it is wise to be prepared to be an educator and referral agent. You don’t have to be an HIV advocate or educator, but it’s likely when you disclose the person is going to have lots of questions. You may feel ready and open to answering them or you might not. Either is okay.

It can really help to arm yourself with proven research or, at least, know where to guide your partner, should they ask, to services that are available to assist with easing doubts and addressing apprehensions.

Remember, counsellors and peer support are both here for you and are able to give you that space to chat. Don’t be afraid to reach out. We are also available for the people in your life to educate and support them.

HIV/AIDS Legal Centre Inc. (HALC)

The HIV AIDS Legal Centre (HALC) is a not-for-profit, specialist community legal centre, and the only one of its kind in Australia. HALC provide free and comprehensive legal assistance regarding HIV or Hepatitis related legal matters. HALC also aim to undertake education and law reform in areas relating to HIV and Hepatitis, as well as provide legal training, education, and experience to employees and volunteers.

HALC are able to provide you with legal advice and assistance, including information about disclosing your diagnosis in Western Australia , and other states and territories in Australia.

To find out more about HALC or to seek legal advice and assistance, please visit their webpage here.

Your status doesn’t change the person you are

Do not allow people to suggest to you that you are any less desirable or worthwhile if you are living with HIV. You have your strengths, weaknesses, interests, quirks and the things that make you amazing. Having HIV doesn’t reduce any of the things that make you beautiful, unique and worthy of love.

You are not wasting other people’s time either. Think about it another way; you wouldn’t feel like you were “wasting time” if you had fertility issues or a chronic illness you didn’t mention on your profile or first date. HIV is just one facet of you and all of you is worth getting to know.

Many of us know that it takes much strength to fight stigma because of who we are. It can take practice to be proud. It takes strength to move past obstacles and barriers. Don’t be afraid to project that power.

Stay connected to WAAC:

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Which Countries Restrict Travel to People With HIV?

It was only in 2010 that the United States finally lifted its 22-year ban on travelers with HIV , a law that prohibited all infected persons from obtaining tourist visas or permanent residence status in the U.S.. The order, initiated by George H.W. Bush in 2008, was made official by Barack Obama on January 4, 2010.

While efforts are being made to end similar laws throughout the world, the Global Database on HIV-Specific Travel & Residence Restrictions (a joint European initiative published by the International AIDS Society) reports that as of 2023, 56 out of 200 countries are known to have entry regulations for people living with HIV, and seven of these countries will categorically refuse entry without exception. In some of these countries, entry may be allowed, but there are restrictions depending on the length of stay. For example, 54 countries have restrictions on stays over 90 days (student and work visas); whereas less than 10 countries have laws that can affect travelers visiting for less than 90 days (tourists). Furthermore, 18 of these countries will deport visitors discovered to have HIV.

HIV Travel Restrictions in Practice

It is important to note, however, that there is often a lack of clarity about these laws, with some either not addressing HIV directly (describing only "infectious disease" concerns) or not enforcing the laws all that stringently, if at all. As such, the assessments provided below are couched in terms that best reflect whether an action "will," "can" or "may" take place.

Similarly, there is a lack of clarity about the import of antiretroviral drugs —whether the drugs are allowed for personal use; how much can be brought in if they are permitted; or if possession of such constitutes the right to deny entry.

For these reasons, it is advised that you always speak with the consulate or embassy of any of the listed destinations if you plan to visit.

Countries With Restrictions for People Living with HIV

Algeria (>90 days)

Aruba (>90 days)

Australia (>90 days)

Azerbaidjan (>90 days)

Bahrain (>90 days)

Belize (>90 days)

Bhutan (>2 weeks)

Bosnia Herzegovina (>90 days)

Brunei (no entry, will deport)

Cayman Islands (>90 days)

China (>90 days, will deport)

Cuba (>90 days)

Cyprus (>90 days)

Dominican Republic (>90 days)

Egypt (>90 days, will deport)

Equatorial Guinea (no entry, will deport)

Honduras (>90 days)

Iran (>90 days)

Iraq (>10 days, possible deportation)

Israel (>90 days)

Jordan (no entry, will deport)

Kazakhstan (>90 days)

Kuwait (>90 days, will deport)

Kyrgyzstan (>60 days)

Lebanon (>90 days, will deport)

Malaysia (>90 days, will deport)

Marshall Islands (>30 days)

Mauritius (>90 days)

Montserrat (>90 days)

Nicaragua (>90 days)

North Korea (will deport)

Oman (>90 days, will deport)

Papua New Guinea (>6 months)

Paraguay (>90 days)

Qatar (>1 month, will deport)

Russia (>90 days, will deport)

Samoa (>90 days)

Saudi Arabia (>90 days, will deport)

Seychelles (>90 days)

Singapore (>90 days)

Slovakia (>90 days)

Solomon Islands (no entry, will deport)

St. Kitts and Nevis (>90 days)

St. Vincent and Grenadines (>90 days)

Sudan (>90 days)

Suriname (entry restrictions)

Syria (>90 days, will deport)

Tonga (>90 days)

Tunisia (>30 days)

Turks and Caicos Islands (>90 days)

United Arab Emirates (UAE) (no entry, will deport)

Uzbekistan (>90 days)

Virgin Islands (>90 days)

Yemen (no entry, will deport)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Medical examination of aliens—Removal of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection from definition of communicable disease of public health significance. Final rule . Fed Regist. 2009;74:56547–56562.

The Global Database on HIV-Specific Travel & Residence Restrictions. Regulations on entry, stay and residence for PLHIV .

By James Myhre & Dennis Sifris, MD Dr. Sifris is an HIV specialist and Medical Director of LifeSense Disease Management. Myhre is a journalist and HIV educator.

HIV/AIDS Legal Centre Inc. (NSW)

Guides to HIV and the law

- Annual Reports

- Submissions

- Volunteering

- News and Events

- Contact HALC

HALC produces a number of guides to HIV and the law. We endeavour to keep these documents up to date, but please note that the information in the Guides is not a substitute for legal advice. Please contact us for advice if you have a specific legal problem.

They are available for download below as PDF documents.

Disclosing your HIV Status in New South Wales

A Guide for people living with HIV in NSW. When are you legally required to disclose your HIV status?

Click on image to download (780kB, February 2023)

Disclosing your HIV status in Queensland

A guide for people living with HIV in Queensland. This guide explores when you are legally required to disclose your HIV status as well as non-legal considerations of disclosure.

Click on image to download (December, 2023)

Disclosing your HIV status in South Australia

A Guide for people living with HIV in South Australia. When are you legally required to disclose your HIV status? This new Guide, produced in association with Positive Life South Australia looks at a range of situations where disclosure of HIV may or may not be legally required.

Click on image to download (239kB, December 2013)

Disclosing your HIV Status in Western Australia

A Guide for people living with HIV in Western Australia. When are you legally required to disclose your HIV status? This Guide looks at a range of situations where disclosure of HIV may or may not be legally required. Please note the information in this Guide is specific to Western Australia, and the laws are different in different States and Territories.

Click on image to download (April 2022)

P ositive Migration Guide

Click on image to download the Guide (Size 1.3MB, November 2021)

A Guide for Women living with HIV in NSW

This Guide is designed for women living with HIV and the service providers who work with them. Due to the nature of the HIV epidemic in Australia, the needs of women with HIV are often overlooked or misunderstood. The Guide provides basic information on some of the legal issues faced by women with HIV in NSW.

Click image to download (172KB, January 2012)

Probate Guide

This Guide explains the relevant law in NSW on probate and succession. It is designed to demystify the process of estate distribution in NSW. It covers the following areas: How to distribute an estate; Applying for Probate; What happens when there is no will; Administration in NSW.

Please contact us for more information about the updated Guide and annexures.

Click image to download (124KB, December 2011)

Travel and HIV

Having HIV should not impose too many restrictions on travelling overseas on holiday. The following websites provide further information about countries with restrictions. PLHIV Organisations around Australia (for example Positive Life NSW) will also be able to provide further practical advice about travelling with your HIV medication.

HIV Travel and Residence Restrictions

Criminal Transmission of HIV: A Guide for Legal Practitioners

Click image to download (328KB, April 2009)

HIV Sentencing Kit

A Guide for legal representatives of people living with HIV who may be facing a custodial sentence through the criminal justice system.

Click image to download (256kb, 2004)

We hope to revise and update this Guide in the near future.

- Publications

- Privacy Statement

Telephone : 02 9492 6540 Email : [email protected] Street Address : 414 Elizabeth Street, Surry Hills, NSW 2010 ABN: 39 045 530 926

The HIV/AIDS Legal Centre Inc. acknowledges the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation, from where we work, and all Traditional Owners of country throughout Australia. We recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ continuing connection to land, place, waters and community. We pay our respects to them, their heritage and cultures; and to elders both past and present.

Does HIV/AIDs Stop You From Entering Australia?

Most visa applicants must meet minimum health standards before the Australian Government will grant a visa.

Australia has a duty to protect its citizens from the introduction of dangerous or infectious diseases from visitors or migrants to our country.

Visa applicants are required to complete a HIV blood test, along with other medical examinations, if they are:

- over 15 years of age;

- applying for a permanent residency visa; and/or

- intending to work (or study to become) a doctor, nurse, dentist, or paramedic in Australia.

Applicants may also be required to undergo a HIV test if:

- under the age of 15 years old;

- they have a history of blood transfusions; and

- there is a clinical indication that the applicant may be HIV-positive (or the biological mother was HIV positive).

The Australian Government generally do not consider HIV or hepatitis to be a threat to public health unless the applicant:

- plans to work as a doctor, dentist, nurse, or paramedic in Australia;

- has a certain level of viral load; and

- intend to undertake procedures where there is a risk of contact between the visa applicant’s blood and the patient’s open tissue.

Transparency

It is extremely important to be transparent with the Department of Home Affairs (‘Department’).

If a visa applicant is HIV-positive, has hepatitis or a family member is HIV-positive/has hepatitis, the Medical Officer of the Commonwealth (MOC) will determine whether the applicant is likely to be a significant cost to the Government in health care services.

Being HIV positive does not automatically mean that the applicant will be denied.

Most people fail the health requirement due to the expensive costs associated with antiretroviral therapy.

The Australian Government has the discretion to ‘waive’ the health requirement on certain visas.

It can be waived based on compassion grounds determined on a case-by-case basis.

For professional consultation on how HIV/AIDS affects your ability to enter Australia, contact Bambrick Legal today:

- Schedule a professional consultation with our specialists here

- Call us on 08 8362 5269

- Like us on Facebook

- Follow us on LinkedIn

Please note: Our migration and citizenship consultations are provided on a fee basis.

Related Blog – Health Requirements & Your Visa

Business & Commercial Law

Corporate & personal insolvency, dispute resolution, employment law, migration & citizenship law, notary public, property law, taxation law, wills, estates & probate, send us a message, for enquiries, please fill in the following contact form.

- Immigration to Australia for those who are HIV positive

- Health, Visas & Immigration

Introduction

Australian visas can be subject to a requirement which commits applicants to demonstrating that they meet certain health criteria.

In order to determine an applicant’s capacity in which to do this, certain temporary and most permanent visa applicants, need to undertake a health examination to satisfy the Department of Immigration & Border Protection (‘DIBP’) that they meet those criteria, details of which we will explore below. An immigration health check in this respect, can and often does, include a HIV test.

The health criteria Where applicable, affected visa applicants are assessed against a number of different health requirements which are contained across Schedule 4 of the Migration Regulations 1994. The requirement in each criterion generally requires applicants to be assessed against the following:

1. Whether the non-citizen is free from tuberculosis; and

2. Whether the non-citizen is free from a disease or condition that is, or may cause him/her to be, a threat to public health in Australia or danger to the Australian community; and

3. Whether the non-citizen is free from a disease or condition which would be likely to require health care or community services or, meet the medical criteria for the provision of a community service and that the provision of such services would be likely to:

i. result in a significant cost to the Australian community in the areas of healthcare and community services; or

ii. prejudice the access of an Australian citizen or permanent resident to health care or community services.

This test applies, regardless of whether the healthcare or community services will be used in connection with the non-citizen with the relevant disease or condition.

Discussion Whilst the first two of the above requirements are not generally relevant in our view to those with HIV, the third one usually is.

In this respect, the DIBP in carrying out an assessment of an applicant’s capacity to satisfy this requirement engages the services of a medical officer to provide an opinion as to whether an affected applicant’s condition would likely result in significant healthcare and community service costs if a visa were to be granted. The current DIBP policy threshold for the level of costs regarded as being significant is $40,000.00.

For temporary visa applicants, the estimated cost for their proposed stay in Australia is assessed over the period that the visa is intended to be granted for. For permanent visa applicants, the time period for estimating costs is generally assessed over a five (5) year period (but can be longer).

Because of that threshold and the relatively high costs of the Highly Active Anti-Retroviral Therapy program, it is often the case (depending on the nature of the applicant’s viral load and condition), that a HIV affected person is unable to satisfy the relevant health criterion.

Generally speaking and despite the foregoing, HIV positive applicants who are not on treatment and not anticipated to be for the duration of any visa, can receive lower costings or even meet the health criteria for shorter term visas and because of this, care needs to be taken in terms of what period of stay is proposed in any temporary visa application.

Is it possible to live permanently in Australia if the non-citizen is HIV positive?

The answer to this is maybe. This depends on what type of visa the person has applied for and in certain circumstances the health criterion which can capture HIV positive applicants can be waived. To this end, health waivers can be obtained for a range of family, skilled and other visa types but it is not universally available. A health waiver can be accessed by demonstrating that certain circumstances exist which warrant a waiver of the relevant health criterion in the first instance.

What factors are considered for a health waiver?

The circumstances that the DIBP will take into consideration in terms of determining whether a health waiver should be granted, generally include:

1. The impact on any Australian citizen children and the extent of any family ties;

2. The effect on an applicant’s health if forced to relocate;

3. The benefits the affected applicant and/or their family members can bring to the Australian community and the economy more generally by allowing the waiver;

4. The applicant and/or any sponsor’s ability to offset the potential costs of treatment; and, amongst other things

5. Any other relevant factor(s).

If a non-citizen is HIV positive can they get a partner visa for example?

The answer to this is yes potentially they can. Partner visas are one of the visas that do have a health waiver embedded within them however this is by no means a guaranteed proposition that an affected non-citizen will succeed with it.

An affected non-citizen applicant for a visa which has a health waiver provision needs to explore as a matter of first principles whether there is scope for them to argue based on the foregoing circumstances, entitlement to such a waiver.

For any visa applicant, careful consideration needs to be applied towards whether the person can meet the legislative requirements to even be able to make an application, as well as to be granted the visa. This is no different but perhaps is even more amplified, for those who are HIV positive.

Making a visa application for a HIV positive person will often require careful strategic considerations in terms of identifying an appropriate visa option which has a health waiver provision. Once this is identified, and in conjunction with any treating providers, one of the first things to do is to establish the full extent of the condition in terms of matters such as the current CD4+ cell count, what treatment algorithm is being pursued as well as whether there are co-infection issues amongst a whole range of other things.

Once and in conjunction with establishing the health landscape, detailed preparation and evidence gathering needs to be applied towards the chosen pathway such that despite the diagnosis, the affected applicant has optimum prospects towards being able to enter or remain in Australia.

Contact us today for a confidential discussion about how we can help »

[email protected] Phone: 1300 193 326

Related Posts

A Comprehensive Guide to Understanding Australia’s Skilled Nominated Visas

Skilled Migration Boost To Drive Workforce Growth in WA

Take a day off: a look at australian public holidays & celebrations, tech triumphs down under: top 10 technologies invented in australia.

- Citizenship

- Employment & Immigration

- Family & Partner Visas

- Immigration Law Specifics

- Immigration News

- Migration & Culture

- News and Updates

- Sporting visa

- Students and Student Visas

- TIL Archived

The facts about HIV

- HIV in Australia

- HIV Prevention

- Getting tested for HIV

- Been Diagnosed with HIV?

- People with HIV

- HIV Law, Travel & Migration

Select from a topic below

HIV in Australia: we’ve come a long way but there’s more to do

Emeritus Professor, Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society, La Trobe University

Disclosure statement

Marian Pitts receives funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council and the Australian Research Council.

La Trobe University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

In the three decades since the virus was identified, Australia has done well by international standards in keeping HIV infection rates down. But certain aspects of our national approach continue to risk the national prevention strategy, and stigmatise people with HIV.

The last 32 years have seen numerous advances in HIV, from the early deaths in 1983, including the deaths of four Queensland babies who received blood transfusions, which led to the blood-screening program; through to the introduction of early combination therapy in 1992 and the reduction in people dying from AIDS-related illnesses after the introduction of combination therapy in 1996.

Since 1999, there has been a small but significant yearly increase in the number of people newly diagnosed with HIV; more people living relatively well with HIV increases the risk of exposure through unsafe sex.

Today, there are an estimated 25,708 people living with HIV infection in Australia, the majority of whom are gay men.

The good and the bad

One of the testaments to the medical successes in dealing with the virus is the significant number of HIV-positive people living into old age . They are coping with the same crises that beset us all as we get older, but with the additional burden of a chronic condition that interacts unpredictably with other diseases.

Despite the downsides of ageing, the fact that HIV-positive men and women are growing old is an outcome that far exceeds what we anticipated 30 years ago. Back then, most people infected with the virus could not expect to still be alive after five years.

Sitting alongside these celebrated advances is the necessity of a pragmatic public health approach to HIV and the frequent challenges posed by the need to regulate or legislate on HIV-related matters.

And there’s some good news here too: a strategic and policy-driven approach has been the most consistent feature of Australia’s response to HIV. The brave steps taken by the then-health minister Neal Blewett , and others in successive governments were critical to HIV prevention.

Fundamental to this success was respect for the views of affected communities. A genuinely national approach in the early days, encapsulated in the first and subsequent national strategies, also ensured local – and sometimes parochial – views did not hold sway.

Nonetheless, there remains a conflicted relationship between government and HIV, particularly in the area of criminal law, reflecting society’s double standards with regard to sex and drugs.

Drugs and prison

Perhaps the best evidence of a successful public health initiative to prevent HIV transmission was the establishment and maintenance of needle and syringe exchange programs, early in the epidemic. These contributed to keeping HIV rates among injecting drug users very low indeed.

Only 1.9% of newly-acquired HIV infections in Australia are attributable to injecting drug use and the rate has been around 3% for the past decade. In contrast, an average of one in ten new HIV infections internationally is caused by injecting drug use and, in parts of Eastern Europe and Central Asia, that figure is over 80%.

Despite its clear success, Australia’s well-resourced needle and syringe exchange program is constantly under threat, always at risk of de-funding by a disapproving public (and media). But it remains the single most effective public health measure in Australia to reduce the harms of HIV and other blood-borne viruses.

Unfortunately, the criminalisation and prosecution of illicit drug use still exposes people to risks of blood-borne viruses within the prison system.

The recent introduction of a trial of safe injecting equipment in an ACT prison is a step in the right direction, and there’s a chance other jurisdictions may follow suit. Similarly, the confirmation of a safe injecting facility in Sydney is a leap forward for public health, despite constant attacks from conservative forces.

Sex, crime and stigma

Internationally, sex work has been closely linked with HIV transmission but, in Australia, HIV-prevention messages and consistent condom use have broken this nexus, and rates of HIV remain very low among sex workers.

Still, the regulation of sex work has an even more chequered history. The various states and territories criminalise different elements of sex work , and there are plans in both Western Australia and South Australia to increase the legal attention on it.

But there’s very little hard evidence that a punitive approach improves the health and welfare of sex workers and their clients. Consider the hundreds of charges of soliciting or selling sex (or both) that go through the courts with little obvious deterrent or protective value.

Criminal law has also been used to prosecute potential exposure and transmission of HIV transmission. As with sex work, regulation varies across Australian jurisdictions.

One of the most striking state differences is that Victoria, South Australia and the Northern Territory criminalise HIV exposure (where there’s no transmission) while other states do not. This connection between HIV and the law exacerbates the stigma and discrimination associated with living with the virus.

So when we welcome international HIV communities to Melbourne next month, we must be prepared for not only the praise and celebration of Australia’s long-standing effective HIV response, but also some criticism of our laws and regulations. They continue to support stigma and discrimination and run counter to efforts to make HIV a virus of the past.

This article launches our coverage of the 20th International AIDS Conference , to be held in Melbourne from July 20 to 25. Look out for more pieces in the following weeks and full coverage during the conference.

- Needle exchange

- Preventative health

OzGrav Postdoctoral Research Fellow

Student Administration Officer

Casual Facilitator: GERRIC Student Programs - Arts, Design and Architecture

Senior Lecturer, Digital Advertising

Manager, Centre Policy and Translation

After 37 years of pioneering health journalism, community engagement, and empowerment through information, we have now ceased operations.

This website will be accessible until September 2025, with all the information being up to date as of July 2024.

If you are a supplier, or another partner you can contact our legacy email address as [email protected] with any queries.

We extend our heartfelt thanks to everyone who supported our vision for a world where HIV is no longer a threat to health or happiness. Together we have made a difference.

With Gift Aid, your generous donation of £ 10 would be worth £ 12.50 at no extra cost to you.

I am a UK taxpayer and I understand that if I pay less Income and /or Capital Gains Tax than the amount of Gift Aid claimed on all my donations in the relevant tax year, it is my responsibility to pay any difference.

In our 35th year we’re asking people to donate £35 – that’s just £1 for every year we’ve been providing life-changing information. Any donation you make helps us continue our work towards a world where HIV is no longer a threat to health or happiness.

- £5 allows us to reach millions of people globally with accurate and reliable resources about HIV prevention and treatment.

- £10 helps us produce news and bulletins on the latest developments in HIV for healthcare staff around the world.

- £35 means we can empower more people living with HIV to challenge stigma with our information workshops, videos and broadcasts.

HIV and travel

- Make sure you pack enough of your anti-HIV drugs to cover your trip.

- Some live vaccinations are not appropriate for people with HIV.

- Some countries refuse work or residency visas to people living with HIV.

Many people living with HIV travel regularly for work, business, study, and for pleasure. In most cases, HIV is not a barrier to travel and holidays. This page provides an introduction to some of the issues you may want to think about if you are planning to travel.

As for other long-term health conditions, it is sensible to consider your health and medication when you make your travel plans. At the most basic level, consider if you are well enough to undertake the trip you are planning.

People living with HIV are able to travel to most countries of the world. But some countries have restrictions on entry for people with HIV, most often for people applying for a work or resident’s visa. See Travel restrictions below.

Also, find out if you need any vaccinations or other preventive medicines, and if it is safe for you to have them. What vaccinations you might need depends on where you are travelling to. If you are accessing travel vaccinations through your GP, it is important that they know you have HIV so they can give you the most appropriate care. It’s also important your GP knows about all the drugs (including anti-HIV drugs) you are taking, in case there are any possible interactions with drugs you might be given for travelling, such as anti-malarials or antibiotics. People with HIV are recommended to avoid some live vaccinations. Find out more on our page on the recommended vaccinations for people living with HIV.

Travelling with HIV treatment

Temporarily switching to injectable hiv treatment, treatment breaks, timing your doses, accessing medical treatment away from home, travel restrictions.

It might be very difficult, or even impossible, to get supplies of your medication once you’ve left home – even if you are just taking a short trip in the UK or Europe. Therefore, make sure you take enough of all your medicines with you to last the full duration of your trip. It might be wise to count out your medicines before you travel and to take a few additional doses just in case you are delayed.

It’s safest to carry your medication in your hand luggage, as this is less likely to get lost. Or you may choose to put some in your hand luggage and some in your suitcase, in case either bag is lost. If you are travelling to another country it makes good sense to have a copy of your prescription or a letter from your doctor explaining that your medicines are for a chronic medical condition. Find out more on our page on travelling with HIV medication .

If you feel uncomfortable about travelling with your HIV medication or are concerned about entry restrictions for people with HIV, one option might be take injectable HIV treatment. Depending on what is available where you are, your doctor may be able to provide an injection which will cover you for the duration of your trip. You may need to switch back to daily tablets when you return.

At the time of writing, the only complete HIV treatment provided by long-acting injections is a combination of cabotegravir and rilpivirine. In Europe, the brand name for injectable cabotegravir is Vocabria, while the brand name for injectable rilpivirine is Rekambys. In North America and Australia, the two drugs are packaged together, with the brand name of Cabenuva.

The injections can be taken either once a month or every two months. They would not suitable for a trip of longer than two months. For more information, see our page on cabotegravir and rilpivirine injections .

Treatment breaks are not recommended. If you are thinking of taking a break from your HIV treatment to travel, then you should discuss the possible risks of this with your doctor. These risks include developing resistance to your drugs, being more vulnerable to health problems in the future and – if you have a low CD4 cell count – of becoming ill while you are not taking treatment.

If you are travelling across time zones, this will have implications for the time you take your medication. Generally, it’s best to adapt to the time zone of your destination as quickly as possible – if you usually take medication with breakfast at home, you should take it with breakfast during your trip. Keeping the same routines around pill taking will probably help your adherence.

undetectable viral load

A level of viral load that is too low to be picked up by the particular viral load test being used or below an agreed threshold (such as 50 copies/ml or 200 copies/ml). An undetectable viral load is the first goal of antiretroviral therapy.

Measurement of the amount of virus in a blood sample, reported as number of HIV RNA copies per milliliter of blood plasma. Viral load is an important indicator of HIV progression and of how well treatment is working.

A drug-resistant HIV strain is one which is less susceptible to the effects of one or more anti-HIV drugs because of an accumulation of HIV mutations in its genotype. Resistance can be the result of a poor adherence to treatment or of transmission of an already resistant virus.

chronic infection

When somebody has had an infection for at least six months. See also ‘acute infection’.

The act of taking a treatment exactly as prescribed. This involves not missing doses, taking doses at the right time, taking the correct amount, and following any instructions about food.

If you are stable on treatment with an undetectable viral load, then taking one dose of your drugs a few hours early or late, because of a change in time zones, will not usually cause problems. You can get more detailed advice on our page on travelling with HIV medications . You can also ask for help from your doctor or pharmacist.

If you live in the UK and are travelling elsewhere in the country, you should contact the nearest accident and emergency department if you need emergency care. You can be seen by a GP away from home as a ‘temporary resident’ if your trip is for under two weeks. If you are entitled to free NHS care, you can get this anywhere in the UK.

The UK has agreements with some countries allowing for free or reduced cost medical care that a person may need. This includes members of the European Union, Australia and New Zealand, but there are restrictions on the types of medical treatment that are covered. UK residents should carry a Global Health Insurance Card (GHIC) when travelling.

It may also be wise to consider taking out travel insurance. Most policies specifically exclude treatment for a pre-existing medical condition (this would include HIV), but will still provide cover if you have an accident or become ill with something unrelated to HIV. Some companies provide travel insurance cover that includes HIV. You can get more detailed information on our page on travel insurance.

A number of countries restrict entry for people with HIV. This means that foreigners with HIV may be refused entry, denied permission to work or settle, or even be deported.

A few countries ban all foreign HIV-positive individuals from entering a country; others have no entry restrictions for tourists but require individuals to be HIV negative in order to apply for a work or residence permit. There's more detailed information on our page on travel restrictions.

- About UNAIDS

- Global AIDS Strategy 2021-2026

- United Nations declarations and goals

- UNAIDS governance

- UNAIDS Programme Coordinating Board

- Results and transparency portal

- UNAIDS Cosponsors

- UNAIDS ambassadors and global advocates

- UNAIDS leadership

- UNAIDS evaluation office

- UNAIDS ethics office

- UNAIDS transformation

- Sustainability of the HIV response

- Community pandemic response

- Education Plus Initiative

- Global alliance to end AIDS in children

- Equal access to cutting edge HIV technologies

- Save lives: Decriminalize

- Global council on inequality, AIDS and pandemics

- Resources and financing

- Global HIV Prevention Coalition

- Global Partnership to Eliminate Stigma and Discrimination

- 2025 AIDS targets

- AIDS and SDGs

- Community mobilization

- Fast-Track cities

- H6 partnership

- HIV prevention

- HIV treatment

- Human rights

- Key populations

- Private sector and the AIDS response

- Security and humanitarian affairs

- Social protection

- Universal health coverage

- Young people

Press centre

- Publications

- Infographics

- FAQ on HIV and AIDS

- World AIDS Day

- Zero Discrimination Day

- Latest data on HIV

- Data on key populations

- Laws and policies

- HIV financial resources

- Technical Support Mechanism

- Learn about HIV and AIDS

- Take action

- Become a donor

- Investment Book

- Work for us

Press Release

Press release

Unaids and undp call on 48* countries and territories to remove all hiv-related travel restrictions.

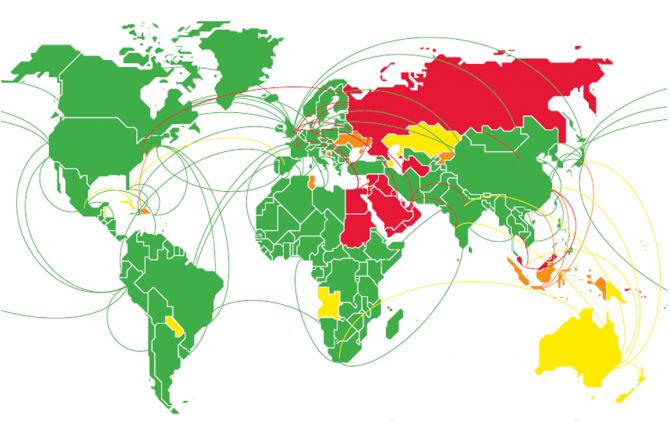

New data show that in 2019 around 48* countries and territories still have restrictions that

New data show that in 2019 around 48* countries and territories still have restrictions that include mandatory HIV testing and disclosure as part of requirements for entry, residence, work and/or study permits

GENEVA, 27 June 2019— UNAIDS and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) are urging countries to keep the promises made in the 2016 United Nations Political Declaration on Ending AIDS to remove all forms of HIV-related travel restrictions. Travel restrictions based on real or perceived HIV status are discriminatory, prevent people from accessing HIV services and propagate stigma and discrimination. Since 2015, four countries have taken steps to lift their HIV-related travel restrictions—Belarus, Lithuania, the Republic of Korea and Uzbekistan.

“Travel restrictions on the basis of HIV status violate human rights and are not effective in achieving the public health goal of preventing HIV transmission,” said Gunilla Carlsson, UNAIDS Executive Director, a.i. “UNAIDS calls on all countries that still have HIV-related travel restrictions to remove them.”

“HIV-related travel restrictions fuel exclusion and intolerance by fostering the dangerous and false idea that people on the move spread disease,” said Mandeep Dhaliwal, Director of UNDP’s HIV, Health and Development Group. “The 2018 Supplement of the Global Commission on HIV and the Law was unequivocal in its findings that these policies are counterproductive to effective AIDS responses.”

Out of the 48 countries and territories that maintain restrictions, at least 30 still impose bans on entry or stay and residence based on HIV status and 19 deport non-nationals on the grounds of their HIV status. Other countries and territories may require an HIV test or diagnosis as a requirement for a study, work or entry visa. The majority of countries that retain travel restrictions are in the Middle East and North Africa, but many countries in Asia and the Pacific and eastern Europe and central Asia also impose restrictions.

“HIV-related travel restrictions violate human rights and stimulate stigma and discrimination. They do not decrease the transmission of HIV and are based on moralistic notions of people living with HIV and key populations. It is truly incomprehensible that HIV-related entry and residency restrictions still exist,” said Rico Gustav, Executive Director of the Global Network of People Living with HIV.

The Human Rights Council, meeting in Geneva, Switzerland, this week for its 41st session, has consistently drawn the attention of the international community to, and raised awareness on, the importance of promoting human rights in the response to HIV, most recently in its 5 July 2018 resolution on human rights in the context of HIV.

“Policies requiring compulsory tests for HIV to impose travel restrictions are not based on scientific evidence, are harmful to the enjoyment of human rights and perpetuate discrimination and stigma,” said Dainius Pūras, Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health. “They are a direct barrier to accessing health care and therefore ineffective in terms of public health. I call on states to abolish discriminatory policies that require mandatory testing and impose travel restrictions based on HIV status.”

The new data compiled by UNAIDS include for the first time an analysis of the kinds of travel restrictions imposed by countries and territories and include cases in which people are forced to take a test to renew a residency permit. The data were validated with Member States through their permanent missions to the United Nations.

UNAIDS and UNDP, as the convenor of the Joint Programme’s work on human rights, stigma and discrimination, are continuing to work with partners, governments and civil society organizations to change all laws that restrict travel based on HIV status as part of the Global Partnership for Action to Eliminate all Forms of HIV-Related Stigma and Discrimination . This is a partnership of United Nations Member States, United Nations entities, civil society and the private and academic sectors for catalysing efforts in countries to implement and scale up programmes and improve shared responsibility and accountability for ending HIV-related stigma and discrimination.

*The 48 countries and territories that still have some form of HIV related travel restriction are: Angola, Aruba, Australia, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Belize, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brunei Darussalam, Cayman Islands, Cook Islands, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Egypt, Indonesia, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Kyrgyzstan, Lebanon, Malaysia, Maldives, Marshall Islands, Mauritius, New Zealand, Oman, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Paraguay, Qatar, Russian Federation, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Samoa, Saudi Arabia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Singapore, Solomon Islands, Sudan, Syrian Arab Republic, Tonga, Tunisia, Turkmenistan, Turks and Caicos, Tuvalu, Ukraine, United Arab Emirates and Yemen.

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS unites the efforts of 11 UN organizations—UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank—and works closely with global and national partners towards ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at unaids.org and connect with us on Facebook , Twitter , Instagram and YouTube .

Download the printable version (PDF)

Deported, denied access, discriminated against because of their HIV status

Infographic

Interactive map

Data @ Kirby Institute