- Camino Real Trek

- Chagres River Hike & Paddle

- Hike & Paddle Camino de Cruces

- Rick Morales

- Jim Morales

- Segundo Sugasti

- Beatriz Schmitt

- Cesar Gonzalez

- Kandi Valle

- How we do it

Darien Gap Expedition

Private trek only.

Currently, we only offer this trip on a private basis and for a minimum of four (4) people.

5 days / 4 nights | 12 days / 11 nights | 14 days / 13 nights

Explore the inside of one of Central America’s most fabled regions, the Darien. With its exuberant rainforests, endless meandering rivers, and its local people, here is an expedition of a lifetime. Our shortest trip is five (5) days long which includes one travel day in, three (3) days trekking through the jungle, and one travel day back to Panama City. Our longest trek is 14 days total. However we can customize just about any itinerary.

Note : At the moment we are unable to offer this trek for solo travelers, or any groups with fewer than four (4) participants. Also, we require at least six (6) months in advance to organize a trek due to a high demand of dates on our calendar .

Darien National Park Tours and Expeditions in Panama

Nestled in tropical rainforest, up river by dugout canoe, you’ll experience a total immersion in nature. Your expeditions go deep into the traditional lands of the Embera indigenous people of Panama. Embark on a Darien expedition, experience an Embera homestay, and immerse yourself in lush primary rainforest. Through shared meals and adventures, you’ll enjoy an authentic experience of rainforest life and Embera culture.

Rainforest Expeditions and Embera Homestays

We offer the best in guided nature tours, from thrilling rainforest expeditions to tranquil cultural experiences.

Eco Adventures

Embera Tours Panama is 100% owned and operated by Panama’s most popular Embera guide, Garceth Cunampio. Garceth grew up in the Darien so he’s introducing you to his own culture and homeland. Garceth is a “jungle guy.” For some, the rainforest is a challenging place, but for Garceth, it’s home.

Freshly Prepared Embera Foods

Using tropical fruits, Bijao leaves, fresh fish and plantains, our team creates visually stunning dishes for your enjoyment. Every day, our cooks harvest what is in season, incorporating these ingredients into all of our meals.

Homestays in Embera Villages

Experience an overnight in one of our handcrafted, traditional palm huts. Enjoy dinner with a local family, be lulled to sleep by the sounds of nature and wake up to bird song.

Panama City Pickup

We’ll pick you up from your Panama City hotel for day trips and overnight adventures. We take care of your transportation, food, water and logistics. Staying out of town? Get in touch with us and we’ll help you plan.

UNRIVALED BIRDING

Immerse yourself in the bird-rich rainforests of Panama.

“Meeting new people and different lifestyle was best education for our son!” Mara H Clearwater, Florida

“Eye-opening for my 9 and 6 year-old daughters” Jake T Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States

“Highlight of our trip to meet these warm and wonderful people.” travelpal600 Tucker, Georgia

“High Point Of The Panama Cruise” Ken D Sosua, Dominican Republic

“Garceth – an authentic Embera guide – great time!” szyman806 Providence, RI

“Outstanding Adventure in Panama” Mooneyson1 Phoenix, Arizona “Like travelling back in time!”

Barbara O Richmond “unforgettable learning experience for all ages” jolajarek Philadelphia

“HIGHLIGHT of Panama trip” Cathy K Silver Spring, Maryland

“A MUST WHEN IN PANAMA” Derobo Monaco-Ville, Monaco

“highlight of panama trip” cohoqueen1 Vancouver Island, Canada “Garceth is the best!” AndyC C NYC

Darién Jungle Expedition

This is an impressive journey under towering trees through a remarkable ecosystem with an incredible biodiversity: rare animal species such as the black-headed spider monkey (ateles fusciceps) can be spotted with a bit of luck.

The beautifully colored poison darts frogs are often seen on the forest litter. Passing under the virescent canopy is like walking over hundreds of years of fallen leaves, billions of insects and more roots than God himself could map on a sunny afternoon.

This place is so alive it makes the city seem barren, even with it’s millions of people. Here life is at every level, in every direction, with more species that have ever been, and likely ever will be, classified.

6 days 5 Nights

Discover the depth of an untouched forest.

Wildlife and rough nature awaits.

Not for the faint of hearted.

8/10 of activity scale.

The Jungle expedition is for the daring, fit traveller. Not only is it hard on the body, but the mind needs to be fit too.

Jungle location

Sleep in the depth of the forest for two consectuive nights. Trek in the wilderness and become one with nature.

Starting point : Panama City

Our guide will meet you at Albrook Terminal in Panama City at 7:30 A.M on departure day. (Bus from Panama City to Metetí)

We will then take a short bus between Metetí – Puerto Kimba.

From Puerto Kimba we take a 45min boat ride to La Palma

We overnight at the Hotel Tuira in La Palma : Here we get to know the village & the local specialities.

Starting point: La Palma, Darién

We take the boat at 7am to go to La Chunga after after having breakfast in La Palma.

Arrival at La Chunga : Introduction of the local community and the area. We will tell you about our history, our political organization and take you to our fields surrounding the village. You will also get the chance to swim in our natural swimming-pool.

Starting point: La Chunga, Indigenous village

In the morning you will hike on one of the Corredor Biologico Bagre rainforest trails. This is an impressive journey under towering trees through a remarkable ecosystem with an incredible biodiversity: Rare animal species such as the black-headed spider monkey (ateles fusciceps) can be spotted with a bit of luck. The beautifully colored poison darts frogs are often seen on the forest litter. Passing under the virescent canopy is like walking over hundreds of years of fallen leaves, billions of insects and more roots than God himself could map on a sunny afternoon. This place is so alive it makes the city seem barren, even with it’s millions of people. Here life is at every level, in every direction, with more species that have ever been, and likely ever will be, classified.

After dinner ,we will build our camp with you if weather allows, we will adventure out again, into the dark, trying to spot some of the nocturnal species and listening to the jungle come alive.

**Tent for overnight-middle jungle **

We wake up in the middle of the jungle and follow with the Trek through the during the day. To end up at a another Jungle Camp

We are very deep into the jungle by walking. You will experience unspoiled jungle and watch different kind of animals and trees/plants.

True feeling of being alone in the jungle.

**Overnight in a tent with dinner over campfire**

If the weather allows make a short night walk after dinner.

Starting point: Jungle Camp

After breakfast we hike back to La Chunga village slowly and we will arrive to the village in the middle of the day.

Cultural interaction with Emberá

You will discover more aspects of the rich Embera culture.

Your hosts will tell you about their history, their political organization and take you to their fields surrounding the village.

**Overnigt Eco-lodge La Chunga **

You will leave early in the morning, following the many river turns in the middle of the thick mangrove. You will come back to Puerto Kimba and Meteti to reach a bus going to Panama City.

Our Accomodation

We offer two different accommodations for you .

For the Homestay experience and the Birdwatching tour, you will be living in our comfortable Eco Lodge Cabins in our village of La Chunga

During your trip with us you can stay in our comfortable Eco lodge cabins which are located right next to our house. This is part of the Homestay Experience and you will be living side to side with us and our family.

The lodges are simple, with no walls but we have but a solid mosquito net, so you don´t have to worry about bugs in the night! Come experience our homestay experience and live like we do.

Jungle experience

Where is la chunga.

La Chunga is located in the forest of the Darién. It is a very pristine area with lots of wildlife everywhere.

Our village lies out to a small creek that flows in the Rio Sambú which is the easiest reference.

- Book your trip to the Darién here

Follow us on Social Media Help spread the word !

Darien Jungle Cruises & Tours

Top darien jungle travel destinations, why travel with adventure life, recognized by.

The Darien is one of the most famous and yet least visited regions of Panama. The large undiscovered rainforest area of the Darien National Park is a UNESCO world heritage site and counts towards the wildlife-richest areas in the world. The Darien is also a hotspot for birders, with the possibility to spot several different rare species, like the Harpy Eagle. Being hardly accessible, the region is home to several different indigenous communities, who live off of hunting, fishing and farming.

Jungles of the Darien

Canopy Camp

- Anton Valley “El Valle”

- Bocas del Toro

- Colón Province

- Panama City

- Pearl Islands “Las Perlas”

- San Blas Tours

- Baja California

- Mexico City

- Riviera Maya

- French Polynesia

We would like to know your opinion about %s

Please score the following:

What did you like about the %s?

What did you not like about the %s, use the form below to contact us directly..

Please complete all required fields.

Booking details

Submit booking, confirmation, booking info.

First name:

Special requirements:

Total price:

We wish you a pleasant trip Tao Travel 365

Availability

You will be redirected to cart shortly. Thank you for your patience.

Use the calendar below to book this tour.

This is a daily tour.

Who is joining in?

Please select number of adults and children joining the tour using the controls you see below.

Extra items

Please select the extra items you wish to be included with your booking using the controls you see below.

The summary of your tour is shown below.

We are sorry, this tour is not available to book at the moment

Darien Jungle in 3 days – Visit the mysterious Darien Gap

It is a forgotten place, a savage place that shows us the best and worst in us all. The dense jungle topography of the Darien Gap has long been the disastrous end of many adventurers, swallowing lost souls in its ancient embrace. The aura of the jungle, of a million wild souls, is as tangible as water when one bathes. It is another sense, one that comes to the heart rather than the eyes, as soaked in richness as they are.

Both ambitious human aspirations and ultimate despair cross paths in this mystical place, drawing all manner of people into its grasp. Trafficked by merciless smugglers and hopeful migrants alike, the Darien Gap has seen and claimed countless of travelers, while only a few lucky ones were given the privilege to escape its dark fangs.

If you are still reading this, you are most likely an adventurer who will most likely enjoy a trip into raw nature, meeting ancient cultures and participating in their rituals and customs. We are offering expeditions into the Darien jungle for various different degrees of adventure levels. Your personal guide will customize your experience depending on your ambitions and physical constituency.

TOUR OVERVIEW

Day 1: visit palma darien and boat ride on the sambu river to la chunga villages.

We recommend that you arrive at La Palma Darien the day before and stay the night at the La Tuira hotel (~$25 per person). The next morning, at 6:30am, you will be picked up from your hotel by one of our staff. After an information session and a tour of the community you will embark on a fast two-hour boat ride through the beautiful bay of San Miguel before reaching the mouth of the Sambu river. As you progress deeper into the flooded rainforest, the landscape will change as your boat weaves through thick mangrove trees. After two hours we arrive at the Embera village of La Chunga. On the way you will see traditional Embera huts built on stilts and probably some specimen of the local fauna such egrets, herons and, with a bit of luck, a caiman lying on the muddy riversides.

**Overnight at the Eco-Lodge La Chunga**

Day 2: Hike in primary Rainforest of the Darien Gap

In the morning you will hike on one of the Corredor Biologico Bagre rainforest trails. This is an impressive journey under towering trees through a remarkable ecosystem with an incredible biodiversity: rare animal species such as the black-headed spider monkey (ateles fusciceps) can be spotted with a bit of luck. The beautifully colored poison darts frogs are often seen on the forest litter. Passing under the virescent canopy is like walking over hundreds of years of fallen leaves, billions of insects and more roots than God himself could map on a sunny afternoon. This place is so alive it makes the city seem barren, even with it's millions of people. Here life is at every level, in every direction, with more species that have ever been, and likely ever will be, classified.

After dinner back in La Chunga, if weather allows, we will venture out again, into the dark, trying

to spot some of the nocturnal species and listening to the jungle come alive.

**Overnight- Eco-Lodge La Chunga**

Day 3: Cultural Interaction with the Emberas

You will discover more aspects of the rich Embera culture. Your hosts will tell you about their history, their political organization and take you to their fields surrounding the village. You will enjoy their traditional music and dances. They will explain you how they make their beautiful and unique handicrafts: delicately weaved baskets and masks made with two kinds of palm fibers for the women, spectacular wooden sculptures made of hard cocobolo wood and wonderful small art pieces made of vegetable ivory (tagua) for the men.

If the weather allows it you will make a short night walk after dinner.

Day 4: Return from La Chunga Village to Panama City via Puerto Kimba

After saying goodbye to your Embera hosts, you will leave early in the morning, following the many river turns in the middle of the thick mangrove. You will come back to Puerto Kimba where your vehicle or public transportation will be waiting for you for the transfer back to your hotel in Panama City.

Note: Itineraries are not bound to specific hours of the day depending mainly on the tides

of the Pacific Coast communities in Darien.

LODGING & MEALS

The sound of nature is a symphony unlike another. Its music will lull you to sleep as you lie comfortably in your bed, in the middle of the jungle.

The traditional, palafita-style cabins are built on stilts or that rise approximately three meters above the ground. These typical structures are known as "Bujia" (literally, "large house") and are generally constructed along the rivers of the region.

- Breakfast: cooked local vegetables (yuca, name, otoe) accompanied by boiled eggs and fresh shellfish prepared in tomato sauce and natural herbs of choice. Breakfast is accompanied by a cup of coffee or natural tea (sweetened teas are available upon request). Bread and pancakes are optional.

- Lunch: Seafood (including fish of the day, fresh shrimp, and lobsters when in season) or meat (chicken, beef, or pork), accompanied by boiled or mashed potatoes. Traditional Panamanian meals include a plate of rice and beans or other legumes (porotos, lentils) and fried plantains (patacones). Lunch is accompanied by fresh orange juice, lemonade, or coconut water. A sampling of delicious tropical fruits may also be available.

- Dinner: served at sunset, dinner includes a light plate of vegetables with cooked meat and fresh orange juice or lemonade. This will be followed by chicheme, a delicious treat of cooked corn, with or without coconut milk, natural fruits, and drinks.

- Optional: vegetarian meals are available upon advanced notice. Options include native vegetables and legume accompaniments such as beans, poroto, lentils, and guandu. These meals come with an accompaniment of fresh coconut juice, orange juice, or lemonade.

The Eco-Lodge La Chunga features:

- 2 private Bujias with double beds

- 1 shared Bujia that has 2 rooms with 3/4 beds and 3 rooms with double beds

- Potable water in all Bujias

- Shared bathrooms and showers

- Gas lantern use at night (no electricity available)

- Small restaurant with refreshments

- First-aid equipment

Shared Cabin:

Rooms with double bed:

Rooms with single bed:

Private Buja with double bed:

Bathroom with shower:

WHAT’S INCLUDED

- Accommodations for 3 days and 3 nights in Eco-lodge La Chunga in the traditional, indigenous community, or camping tents during the hikes

- All meals (breakfast, lunch, dinner)

- Entrance fee to Corredor Biologico Bagre (National Park Darien)

- Observation of flora and fauna

- Guides with experience who speak English and Spanish

- Hikes to the jungle

- Traditional Emberá hut with full board

- Fee for the indigenous community

- Motor boats and canoe transports

- Luggage attendant support

WHAT’S NOT INCLUDED

- Transportation from Panama City to Darien and back (please see "Getting Here")

- Puerto Kimba Boat taxi to La Chunga ($35 each way)

- Alcoholic Beverages and soft drinks

WHAT TO BRING

- Passport will be required when checking in with the immigration booths at Darien and Puerto Quimba

- Guests may carry flashlights for personal use

- Strong footwear (hiking boots and/or sandals)

- Mineral bottle water and soft drinks

- Waterproof coat or jacket

- Cap, hat, or bandana

- Hiking and/or cargo pants (no jeans)

- Mosquito/Bug Repellent

- Sheets or sleeping bag (the jungle can get cold)

- Personal utensils

- Camera and/or video camera

- Biodegradable soap

- Open mind and strong will

Note: You will be able to rent advisable equipment in La Chunga such as boots, waterproof coats, jacket and camping gear

IMPORTANT ADVICE

Visitors to the darien jungle are advised to be vaccinated against malaria.

- Everyone suffering from heart disease has to show a medical examination clearing you to take part in strenuous activities. This tour is recommended for people in good health and in good condition.

- All accommodations are located in indigenous communities. You will sleep in a indigenous cabins and/or tents. A sleeping bag and a sleeping pad will be offered to you.

- Toilet facilities are really basic pit toilets

- The accommodation in La Chunga village is rustic, but has comfortable beds with fan and mosquito nets. The bathroom has running water

- There is no electricity available

- You will spend your last night in La Chunga

- Travel to the Darien Jungle is enjoyable all year long, however, the best time to visit is the dry season, which lasts from January to July

- Itinerary may vary depending on weather conditions

GETTING HERE

There are two ways to get to La Palma, Darien. Please let us know at least 15 days in advance of your travel plans so that we can make all arrangements.

Option 1: Private Plane from Albrook Airport

We highly recommend this option for groups of 15 to 20 guests. You can charter a private airplane taking you directly to Sambu airport, which is located a short 10 minute boat ride away from La Chunga

Option 2: Public transportation from Albrook Bus Terminal

- Take a bus from Albrook Bus Terminal to Darien-Meteti (5 hours and approx. $9)

- Connect at Meteti Bus Terminal onto a smaller bus to Puerto Quimba (30 min and $2)

- In Puerto Quimba take a Sambu Water Taxi to La Palma where you will spend the night at Hotel Tuira (30 min and $5 for water taxi and approx $20 for hotel)

Once arrived in La Palma, please spend the night at the La Tuira hotel (~$20 per guest). The next morning, at 6:00am, one of our employees will meet you at the hotel to take you on the boat ride to La Chunga.

*Please note that the price paid the the tour does not include Transportation to and from La Chunga. Upon start of your tour the next morning, you will embark on a two hour speed boat ride to La Chunga which costs $22 per Guest each way.

** Traveling to Darien requires that you to check-in with the immigration booths at Darien and Puerto Quimba. They will only ask you for your Passport Information and how long you will be staying. If there are any problems, just explain that you are tourists.

CANCELATION POLICY

Please read our Tour Cancelation Policy before booking.

TOUR CANCELATION POLICY

Tao Travel 365 strives to deliver the best possible customer experience. If at any point you have a question or concern about our service, please call us by phone at +1 (805) 826-3657 or email us at [email protected].

The following cancellation policy applies only for Day Tours (DOES NOT apply for Multi-Day Tours).

TOUR POLICIES

Due to the nature of our business, the logistics involved with organizing tours and the high reservation demand following refund policies apply:

- 100% refund less credit card processing fees will only be granted if booked via our website www.taotravel365.tours AND if canceled more than 7 days before the start of the tour.

- 50% refund less credit card processing fees will be granted for cancellations received less than 7 days AND more than 48 hours before the tour start date.

- No refund will be granted for cancelations received less than 48 hours before the tour start date.

All sales are final.

For all bookings made via outside portals such as, but not limited to Viator, Expedia, Airbnb, please refer and adhere to the respective cancellation policy of the portal that you booked with. If you are unable to realize the reservation, contact us as soon as possible and we will try to arrange and reschedule the same or different tour for you. If you are not at the designated meeting point by the time of your scheduled reservation or pick up, Tao Travel 365 reserves the right not to provide a refund. However, we will always try our best to locate you at the meeting point and call your WhatsApp number, if one was provided. After all, we want you to participate in our tour and have fun. That is our goal!

CANCELED OR POSTPONED TOURS

Occasionally, tours are canceled or postponed due to weather or ocean conditions, mechanical failure, or other unforeseen events. Should this occur, we will attempt to contact you about the cancellations and to inform you of refund or exchange procedures for that tour. For exact instructions on any canceled or postponed tour, please contact us. In the case of a cancellation of your tour by Tao Travel 365, we will refund your tour or schedule you for another tour, as detailed below.

All sales are final. No refunds are available unless a tour is canceled or postponed, or we are given 48 hours advance noticed whereby a 50 percent refund will be awarded. We will offer refunds of the full face value of the tour(s) that are canceled or postponed (or, if a discounted tour, then instead the discounted tour price paid). No refunds are offered on any service, payment processing or convenience fees. To receive a refund for a canceled or postponed tour, contact us at [email protected] within 3 days of the tour cancellation and write "refund" in the subject line. Instructions will be provided in order to obtain your refund.

TOUR EXCHANGES

No tour exchanges are offered by Tao Travel 365. While in some extreme cases we may offer this service (such as a cancellation by Tao Travel 365), it is not guaranteed and often impossible. Contact us directly by phone at +1 (805) 826-3657 or by email at [email protected] to inquire about tour exchanges. Fees may apply.

sa***@ta**********.tours

+507-6109-3118 +1 (805) 826-3657 +1 (805) TAO-365 7

Ave 5B Sur Panama City, Panama

WhatsApp us

Birds of Canopy Camp Darien

High Season: $3,350 — Green Season: $2,335 Rate in US$ per person (+ taxes), double occupancy

Canopy Camp

7-night, all-inclusive birding package.

Darién, as this entire eastern-most region of Panama is called, is perhaps the most diverse and species-rich region of Central America. Long coveted by avid birders as an impenetrable haven for rare species, this region is now readily accessible by a highway extending through the spine of Panama right into the heart of this bird-rich land. During this exciting, highly recommended 7-night adventure, we visit, en route to the Canopy Camp, the Bayano Reservoir, to look for such specialties as the starkly beautiful Black Antshrike, Rufous-winged Antwren and stunning Orange-crowned Oriole. In Darién, we visit large tracts of mature lowland rainforest to seek out Rufous-winged Antwren, Bare-crowned Antbird and Golden-green Woodpecker; and the swampy meadows along the Pan-American Highway, the haunts of the magnificent Spot-breasted Woodpecker! We will enjoy great birding on this Panama wildlife tour through the mature secondary forests, tranquil lagoons and riversides of this region, where we hope to get excellent views of Stripe-throated Wren, Black-collared Hawk, Black-capped Donacobius, Yellow-hooded Blackbird, Large-billed Seed-Finch and others.

After each Panama wildlife tour, we will spend all our nights at Canopy Camp Darien, where we will enjoy comfortable, large, safari-style tent accommodations, each with full-size beds, private bathroom facilities with refreshing showers, flush toilets, electricity from solar panels, and fans. The protected forests of the Filo del Tallo Hydrological Reserve surround the camp. In the vicinity of the camp itself we will enjoy such regional specialties as Gray-cheeked Nunlet, White-headed Wren, Rufous-tailed Jacamar and Pale-bellied Hermit right in the gardens! This Panama wildlife tour offers other surprises, such as Spectacled Parrotlet, Dusky-backed Jacamar, Double-banded Graytail, King Vulture and the majestic Harpy Eagle! You are sure to have the birding adventure of a lifetime!

7 Night Package (2024): High Season: $3,350 — Green Season: $2,335

**add 3 nights at Canopy Tower or Canopy Lodge for only $1,110 (High) or $780 (Green)

7 Night Package (2025): High Season: $3,468 — Green Season: $2,417

**add 3 nights at Canopy Tower or Canopy Lodge for only $1,1149 (High) or $808 (Green)

***Packages normally begin on Sundays

Rates in US$ per person (+ taxes), double occupancy

On the first night of this Panama wildlife tour, accommodations will be at the Riande Aeropuerto Hotel or at the Crowne Plaza Panama Airport Hotel in Panama City. Your guide will meet you bright and early (around 6:30 am) in your hotel lobby the next morning to head to the Canopy Camp, where you will stay for the following 6 nights. This is an all-inclusive tour with an active itinerary—daily morning and afternoon guided birding trips are included for the full duration of your Panama wildlife tour. The tour finishes mid-afternoon on the last day in Panama City.

Visiting Darién is truly an adventure, so expect the unexpected and be prepared for excitement around every corner! Our guides know well how to find the regional specialties that live here and how to dodge the ever-changing conditions of the region from season to season. The itinerary, therefore, is very flexible to our guests’ desires and targets and current conditions. Some sites are accessible year-round, while others are only worth visiting and accessible during certain seasons. Regardless, our guides and staff are bound to show you many, many birds and a great experience in the wilderness of Darién!

Panama’s National Bird: The Harpy Eagle

Darién is a stronghold for Harpy Eagles and other large forest raptors, and holds Central America’s largest population of this rare and majestic bird. If there is a site available to visit, whether an active nest or a fledged juvenile in a reliable location, it will be included in the itinerary. We can keep you informed as your trip gets closer. Please keep in mind that we can never guarantee the sighting of a Harpy Eagle (or anything in nature), even at a reliable site, but we will be sure to try if there is a chance!

If there is no nest site or juvenile bird to visit, there is still always the chance to come across a Harpy Eagle during your stay. Over the past few years, we have had Harpy Eagle sightings at several of the birding sites we visit, including a few times at the Canopy Camp itself!

Check out our Harpy Eagle & Crested Eagle Logs here:

- Harpy Eagle Log

- Crested Eagle Log

Harpy Eagles live in remote mature forest, and a full-day trip may be required to visit the site available. The following description gives you an idea of what a Harpy Eagle excursion entails:

The Harpy Eagle is our target for the day! Today we will start very early, long before sunrise, and drive to Yaviza, at the end of the Pan-American Highway. Arriving at dawn in Yaviza, we will board a “piragua”—a dugout canoe—and traverse the still waters of the Chucunaque and Tuira rivers. The river edges offer shrub and grass habitat, as well as mudflats and beaches depending on the water level. There are plenty of birds to see along the riverside: Neotropic Cormorant, Anhinga, Great Blue, Cocoi, Little Blue, Tricolored, Striated and Capped Herons, Snowy Egret, White and Green Ibises, Yellow-crowned Night-Heron, Pied Water-Tyrant, Bronzed Cowbird, Yellow-hooded Blackbird and both Crested and Black Oropendolas. White-tailed Kite and Black-collared and Common Black Hawks may be found cruising overhead.

Upon arrival in El Real, we can scan the open areas for Spot-breasted Woodpecker and Great Potoo. We will meet a local truck and head south out of town past the airstrip, to the trailhead at the border of Darien National Park! This trail is wide, traversing through lowland rainforest and alongside a river. If very lucky, we may see Harpy Eagle or Crested Eagle, as both of these magnificent raptors roam the dense forests here. Hopefully with some success this morning, we can rest and have a picnic lunch in the field, and continue to bird along the trail. Other large forest eagles, including Ornate Hawk-Eagle, can also be found in the area, as well as Gray-cheeked Nunlet, White-fronted Nunbird, Green-and-rufous Kingfisher, Agami Heron, Red-throated Caracara, Chestnut-backed Antbird (the eastern Panama race shows white dots on the wings), Chestnut-fronted and Great Green Macaws, Scarlet-browed Tanager and more. After lunch and a break, we will retrace our steps and start our way back to El Real, then head back to Yaviza by river. Along the Pan-American Highway, we can scan for bird activity as the sun sets.

The following are brief descriptions of some of the birding areas you may visit during your Panama wildlife tour at Canopy Camp Darien:

Bayano Lake Area & Torti Area

As we drive along the Pan-American Highway, we will scan for roadside birds and open-field raptors including Savanna Hawk and Crested Caracara. At the bridge at Bayano Lake, a great opportunity awaits to see what we can see along the lakeside. This reservoir supports great numbers of water birds, including a large colony of Neotropic Cormorants, as well as Anhinga, Cocoi Heron and the rare Bare-throated Tiger-Heron. We will scan the water’s edge for Purple Gallinule, Pied Water-Tyrant, Smooth-billed Ani and Ruddy-breasted Seedeater. A short trail leading from the water’s edge is a great place to search for Black Antshrike, Bare-crowned Antbird, Rufous-winged Antwren and Golden-collared Manakin. Just 10 minutes down the road at Río Mono Bridge, the surrounding forest is home to One-colored Becard, Black-headed Tody-Flycatcher, Blue Cotinga, Pied Puffbird, Orange-crowned Oriole, Blue Ground Dove and more. We will also scan the river below for Green-and-rufous Kingfisher and the elusive Fasciated Tiger-Heron. The forest edge and scrubby roadsides around Rio Torti offer good opportunities to see Pacific Antwren, Double-banded Graytail and Little Cuckoo. At a lovely Panamanian restaurant in Torti, the hummingbirds at the feeders will no doubt capture our attention, as Long-billed Starthroat, Sapphire-throated Hummingbird, Scaly-breasted Hummingbird, Black-throated Mango and more take their lunch as well; great hummingbird photo opportunities abound throughout this Panama wildlife tour!

Canopy Camp Grounds & Nando’s Trail

Yellow-throated and Keel-billed Toucans call from the towering Cuipo trees; Red-lored and Mealy Parrots fly overhead; White-bellied Antbird, Bright-rumped Attila, White-headed Wren and Golden-headed Manakin sing from the surrounding forests; while Pale-bellied Hermit and Sapphire-throated Hummingbird visit the flowers around camp. Rufous-tailed Jacamar and Barred Puffbird are also seen frequently around the grounds. We will work our way into the forest on “Nando’s Trail,” in hopes of finding Tiny Hawk, Black Antshrike, Great Antshrike, Olive-backed Quail-Dove, Cinnamon Becard, Black-tailed Trogon, Double-banded Graytail, Gray-cheeked Nunlet, Yellow-breasted Flycatcher, Royal Flycatcher and Russet-winged Schiffornis. We will also be looking for groups of Red-throated Caracara, King Vulture and Short-tailed Hawk overhead in the clearings. Ornate Hawk-Eagle, Plumbeous and Zone-tailed hawks are also possible. In the open areas, the verbenas are full of hummingbird and butterfly activity, where we hope to see Violet-bellied Hummingbird, Pale-bellied Hermit, Long-billed Starthroat, Blue-throated Goldentail and if lucky, the stunning Ruby-Topaz Hummingbird feeding here. Spot-crowned Barbet, Olivaceous Piculet, White-headed Wren, Red-rumped Woodpecker and Streak-headed Woodcreeper are other birds we may encounter. If desired, we can hike up the slope to stand in the shadows of two giant Cuipo trees.

There will be an opportunity during the week to explore the grounds of the Canopy Camp at night in search of nocturnal birds and mammals, including Black-and-white and Mottled Owls, Great and Common Potoos, Kinkajous, Central American Woolly Opossum and more!

Birding the Pan-American Highway

We will head southeast and bird the forests and swampy meadows along the road toward Yaviza, at the end of the Pan-American Highway! Black-billed Flycatcher, Sooty-headed Tyrannulet, Jet Antbird, Black Oropendola, Pied Water-Tyrant, Bicolored and Black-collared Hawks, Pearl and White-tailed Kites, Limpkin, Spot-breasted Woodpecker, Ruddy-breasted Seedeater, Yellow-hooded Blackbird, Black-capped Donacobius and Red-breasted Meadowlark can all be found as we head further into Darién.

El Salto Road

El Salto Road extends 6 km north from the Pan-American Highway and ends at the mighty Río Chucunaque. This open road and surrounding dry forest is a great place to search for regional specialties including Golden-green Woodpecker, Double-banded Graytail, Blue-and-yellow and Chestnut-fronted Macaws, Black and Crested Oropendolas, Blue Cotinga, White-eared Conebill, Black-breasted Puffbird, Orange-crowned Oriole and the majestic King Vulture. A trail at the end of the road will take us into low-canopy forest, where we hope to find Bare-crowned Antbird, Pale-bellied Hermit, Olivaceous Piculet, Streak-headed Woodcreeper and Forest Elaenia.

Tierra Nueva Foundation

Adjacent to El Salto Road is the property of the Tierra Nueva Foundation. Fundación Tierra Nueva is a non-profit organization whose main mission is “working towards the sustainable development of people of the Darién Rainforest.” The property is the home of a technical school focusing on applications in agriculture. We will explore the trails of this large, forested property, in hopes of finding Streak-headed Woodcreeper, Yellow-breasted and Black-billed Flycatchers, Red-rumped Woodpecker, Slaty-backed Forest-Falcon, Cinnamon, Cinereous and One-colored Becards, White-eared Conebill, White-headed Wren and the magnificent Great Curassow. We will also search for the eastern race of the Chestnut-backed Antbird, which shows white spots on the wings.

Las Lagunas Road (Aguas Calientes) & Aruza Lagoons

This road extends 12 km south off the Pan-American Highway through open farmland, dry scrub and roadside habitat. The road eventually crosses a stream and ends at some small ponds. Along the roadsides, we hope to find Red-breasted Meadowlark, Spot-breasted Woodpecker, Yellow-breasted Flycatcher, White-headed Wren, Smooth-billed and Greater Anis, Muscovy Duck, Rufescent Tiger-Heron, Southern Lapwing, Blue-headed Parrot, Striped Cuckoo, Scaly-breasted Hummingbird, Ringed and Amazon Kingfishers, Buff-breasted Wren, Bananaquit, Giant and Shiny Cowbirds, Crested Oropendola, and Laughing and Aplomado Falcons. If we’re lucky, we may get a glimpse of a Chestnut-fronted Macaw or a shy Little Cuckoo, both having been seen along this road. At the lagoons, we hope to find Pied Water-Tyrant, Capped Heron, the beautiful Yellow-hooded Blackbird and the extraordinary Black-capped Donacobius—this is great habitat for all these wonderful species.

Quebrada Felix

Quebrada Felix—this newly discovered site awaits exploration! Quebrada Felix is nestled in the base of the Filo del Tallo Hydrological Reserve, and is just a short drive from the Canopy Camp. Surrounded by tall trees and mature lowland forest, we will walk the rocky stream in search of some of Panama’s most wanted species, including Black-crowned Antpitta, Scaly-throated Leaftosser, Speckled Mourner, Ocellated Antbird, Rufous-winged and Moustached Antwrens, White-fronted Nunbird, Wedge-billed Woodcreeper, Royal Flycatcher and the endemic Stripe-cheeked Woodpecker. It is also a great spot to find Fasciated Tiger-Heron, Green-and-rufous Kingfisher, Bicolored Antbird, Golden-crowned Spadebill, Double-banded Graytail and much more. Crested and Solitary Eagles have even been spotted here, a great testament to the mature forest of the area. Quebrada Felix is becoming a favorite spot among our guides and recent visitors!

Lajas Blancas

On this Panama wildlife tour, we eagerly explore the open areas and mixed forests of the area of Lajas Blancas. Lajas Blancas is the closest Embera community to the Canopy Camp, a large town with a population of over 1000 residents. Just 15 minutes away, the area around the community boasts great birding and the opportunity to find many Darien specialties! After turning off the Pan-American Highway, we drive through pasture and open farmland—a great place to see One-colored Becard, Great Potoo, Spot-breasted Woodpecker, Yellow-crowned Tyrannulet, Yellow-breasted Flycatcher, Black Antshrike and Black Oropendola. During the dry season, a bridge across the Chucunaque River provides us easy access to some mature secondary forest where Double-banded Graytail, Rufous-tailed Jacamar, White-winged and Cinnamon Becards, Cinnamon and Golden-green Woodpeckers, manakins and others can be found. Beyond the community, the road continues and there is much more forest, including primary forest at its far reaches, waiting to be explored on your Panama wildlife tour.

Nuevo Vigia

We are off to Nuevo Vigia, an Embera community nestled north of the Pan-American Highway, surrounded by great secondary growth dry forest and two small lakes, all of which attract an enticing variety of birds. The community is accessible by “piragua,” a locally-made dugout canoe. As we coast along the Chucunaque and Tuquesa Rivers, we will keep our eyes and ears open for Chestnut-backed, Crested and Black Oropendolas, Spot-breasted Woodpecker, Common Black Hawk, Yellow-tailed Oriole, Red-billed Scythebill, Capped and Cocoi Herons, White Ibis, Greater Ani, Solitary Sandpiper and other water birds. We will spend the majority of the morning birding a trail toward a small lagoon, a great place to see Black-collared Hawk, Bare-crowned and White-bellied Antbirds, Green Ibis, Gray-cheeked Nunlet, Spectacled Parrotlet, Black-tailed Trogon, Striped Cuckoo, Black-bellied Wren, Little Tinamou, Golden-green Woodpecker and Green-and-rufous Kingfisher! In the town of Nuevo Vigia, local artisans weave colorful decorative masks and plates out of palm fronds and carve cocobolo wood and tagua nuts into animals and plants, and we will have the opportunity to meet some of the community members and admire and purchase some of the beautiful products they make by hand. We will enjoy a satisfying picnic lunch in the village, followed by more great birding around the riversides and scrubby habitat surrounding Nuevo Vigia before heading back to the Canopy Camp.

Aligandi is a huge area with unique scrub forest and much to be explored. We head out from the Camp toward the end of the Pan-American Highway, taking a turn prior to reaching Yaviza. Along the roadsides here, we scan for Red-breasted Meadowlark, Striped Cuckoo, Ruddy-breasted Seedeater, Thick-billed Seed-Finch, American Kestrel and other open area birds. A Great Green Macaw nest is tucked up in the canopy of a huge Cuipo tree, visible from the road, and if lucky, an adult or a chick may be seen poking its head out of the cavity. At Finca Doncella, we continue on foot along the road through the scrub forest, seeking out Spot-breasted Woodpecker, Bat Falcon, Giant Cowbird, Orange-crowned Oriole, Red-billed Scythebill, White-eared Conebill and mixed feeding flocks. It is possible to see macaws flying over as we further explore the area on this Panama wildlife tour.

Please note that the itinerary is flexible, and may change without prior notice due to weather, alterations in habitat or other conditions.

Our Canopy Camp in Darién , Panama is a birder’s paradise. The protected Darién jungle provides a stronghold for Great Green Macaw, Great Curassow and the majestic Harpy Eagle, Panama’s national bird, as well as other endangered wildlife including Colombian Spider Monkey, Baird’s Tapir and America’s most powerful cat, the Jaguar. Some of Panama’s endemic species, such as the Pirre Warbler, Pirre Bush-Tanager and Beautiful Treerunner, are only found here in the far reaches of the Darién Province.

You May Also Like

Butterflies of Canopy Camp Darien

Birds of Central Panama & Darién Lowlands

- Trip Reports

- Featured Sightings

- Meet Raúl Arias de Para

- Meet Our Team

- Meet Our Guides

- Environmental Initiatives

- Social Responsibility

- Community Development

Your browser is not supported for this experience. We recommend using Chrome, Firefox, Edge, or Safari.

Darien National Park

Welcome to the Jungle! At 5,750 square kilometers, Darien National Park is the largest national park in Panamá, and the largest protected area in Central America and the Carribean—not to mention one of Central America’s most untamed regions. This extensive jungle features endless virgin rainforests, premontane and montane forests, cloud forests and dwarf forests, as well as large mangroves. You’ll also find meandering rivers such as the Tuira or the Chucunaque, an astounding array of unique wildlife, including the jaguar and the harpy eagle, plus mountain ranges that reach more than 2,500 meters in elevation. As one of the most important UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Central America, Darien is a Biosphere Reserve and the focus of many conservation efforts in Panamá. In fact, after the Amazon rainforest, Darien National Park is considered the most important “natural lung” in the Americas.

Recommended for true adventurers only, the park is rainy, humid and extremely remote, with two popular areas to visit. One of them is Santa Cruz de Cana, or Cana. Located in the middle of the park along the eastern slope of Cerro Pirre (or Pirre Hill), the area was once a mining town where the Spanish discovered gold in 1665. Today, it’s one of the most pristine outdoor areas in Panamá, and among the top locations in the country for birdwatching. Look out for colorful macaws, tanagers, manakins, eagles and hummingbirds, as well as other wildlife such as howler and spider monkeys, white-lipped peccaries and Baird’s Tapirs. Explore the jungle on one of five hiking trails in the area, which offer views of the forest and the old mining operations.

On the other side of Cerro Pirre, you’ll find Pirre Station—another hiking destination inside the great jungle. Also known as Rancho Frío, this area is replete with lush nature and an abundance of wildlife that includes woodpeckers, monkeys, tamarins and sloths. When you get to Pirre Station, you’ll find a basic dormitory, outhouse and kitchen, but you’ll have to bring your own gear for sleeping and eating.

Getting There This trip is for the truly adventurous, and we highly recommend visiting with a local tour or guide. If you decide to go, you’ll find the park 325 kilometers from Panama City on the eastern edge of the isthmus at the border with Colombia. From Panama City, fly to El Real, the closest community to the park. For something a bit more adventurous, travel by road to the community of Yaviza, and then continue to El Real by boat.

- How to Tie a Tie

- Best Coffee Beans

- How to Shape a Beard

- Best Sweaters for Men

- Most Expensive Cognac

- Monos vs Away Luggage

- Best Luxury Hotel Chains

- Fastest Cars in the World

- Ernest Hemingway Books

- What Does CBD Feel Like?

- Canada Goose Alternatives

- Fastest Motorcycles in the World

Inside the Darién Gap, one of the world’s most dangerous jungles

The darién gap: what to know before you go. wait. maybe don't go.

The Pan-American Highway is an epic 19,000-mile route that starts at Prudhoe Bay in Alaska and terminates at the southernmost end of South America in Ushuaia in the country of Argentina . It’s continuous except for a small section missing along the southern border of Panama, often referred to as one of the most inhospitable places on the planet — this is the Darién Gap. It’s 66 roadless miles of dense, mountainous jungle and swamp filled with armed guerillas, drug traffickers, and some of the world’s most deadly creatures covering the border of Panama and Colombia.

Fer-de-lance pit vipers

Drug traffickers and farc armed guerillas, brazilian wandering spiders, black scorpions, jungle heat and dirty water, spiked chunga palm trees, trench foot, cold war bombs.

The environmental impact on the area and the sheer cost of building roads through it have thwarted any previous attempts. Others are concerned that “the Gap” is a natural barrier against drugs and disease flowing freely into North America and the U.S.

The first-ever successful vehicle expedition through the Darién Gap was led by British army officer Gavin Thompson. His team of six started in Alaska, driving all the way to Panama in a newly created Range Rover. Hitting the Darién Gap, he brought in a team of 64 engineers and scientists to hack their way through the jungle and float the Range Rovers across the rivers.

Thompson and every expedition since ran headlong into what the Gap is most famous for: Things that will kill you . The list of deadly things inside the Gap is lengthy, and dehydration and starvation are the least of your concerns. Instead, you should be concerned with these very real threats.

The fer-de-lance pit viper is one of the most venomous creatures in the Darién Gap. They’re irritable, fast-moving, and large enough to bite above your knees. Antivenom usually solves the problem if you get bitten. But, if left untreated, the venom can cause local necrosis (death of body tissue), leading to gangrene or, in the worst cases, death.

Conflict journalist Jason Motlagh crossed the Gap in 2016 for a Dateline story . After receiving their antivenom kit and instructions for use before the crossing, he said, “If one of us is bitten, we have ten minutes to inject the antivenom before death. We can only carry six vials. If a larger pit viper were to strike, the expert concedes no amount of antivenom would be enough to save us. We might as well lie down and smoke a cigarette until the lights go out.”

It’s becoming increasingly difficult to bring drugs into the U.S., so drug traffickers are turning to other avenues. The lawlessness and lack of many residents make the Darién Gap a perfect path for cocaine and other drugs on their journey from South America.

The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) have made a name for themselves since 1964, terrorizing the government and many cities in Colombia. Many from the group have made their home in the lawless jungles of the Darién Gap. A backpacker from Sweden was shot in the head in 2013 and found two years later. Multiple others have been kidnapped for weeks or months after venturing into the Gap.

Since a peace deal in 2017 with the United Nations, the group has reformed into an official political party, but a few thousand rebels still continue with drugs, arms, and human trafficking.

Spiders fill the jungles of the Darién Gap, but one of the most “medically important” is the Brazilian Wandering spider. “Medically important” is the nice term for “you’re going to have a really bad day if this bites you.”

This family of spiders (there are more than one!) has a leg span of five to seven inches. They wander the jungle floor at night and love to hide in people’s hiking boots , logs, and banana plants. They’ve been nicknamed the Banana spider, as that’s often where people run into them. Bites from this spider can put you in the hospital or, from particularly bad ones, cause death in 2 to 6 hours.

Scorpions look like they’re from another planet. A few species prefer conditions in Colombia and southern Panama and call the Darién Gap home, with the black scorpion being one of those species. Black scorpions can be two to four inches long with a black or reddish-black coloring, which gives them their name.

They live under rocks and logs and hunt for larvae and cockroaches at night. They are part of the thick-tailed scorpion family, giving them their stocky appearance. The sting is very painful but, thankfully, is rarely deadly to humans … as long as you are treated in a safe amount of time.

Even the heat in the jungle can put a serious dent in your mood. Temperatures in The Gap can reach a balmy 95 degrees Fahrenheit with 95% humidity, creating a terrible problem if you run out of water. With trips through The Gap averaging between 20 to 50 days, you had better be prepared to stay hydrated.

There’s a lot of water in the Darién Gap but it is far from clean. Even a sip can hold a host of viruses or parasites that could ruin the rest of your trip. Hopefully, you have a good water filter with you.

Many kinds of trees call the jungle home, and the local people make use of all of them. The fiber from the leaves of the Chunga Palm is used to make everything from furniture, hats, and jewelry to fishing nets.

Perhaps that’s why this palm has one of the best defenses for a tree in the area. Long black spines — up to eight inches long — cover the Chunga to prevent animals from climbing and taking the fruit. Unfortunately for us, these spines are covered in all sorts of bacteria. One brush with a Chunga and you might find yourself with infected puncture wounds embedded with shards of Chunga spines.

During the mid-eighties, Helge Peterson found himself in Colombia trying to complete a motorcycle tour from Argentina to Alaska. A small problem stood in his way: The Darién Gap. Convincing a young German backpacker to make the journey with him, they started their journey together. They began the 20-day trek hauling Helge’s 400-pound BMW motorcycle into the jungle, through rivers and ravines.

At the end of each day, tired and broken, Helge and his backpacking partner would set up camp and start the removal of ticks , sometimes several hundred at a time, from their skin and clothing. Ticks in the area can carry Ehrlichiosis or Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, neither of which you want in the middle of the jungle days or weeks from the nearest hospital.

Trench foot was first described during Napoleon’s retreat from Russia in the winter of 1812, but the name references a condition common during World War I. It originates with wet skin that isn’t allowed to dry. Wet conditions and limited blood flow cause the tissue to tingle or itch, often turn red or blue, and eventually decay. Any open wounds quickly develop fungal infections. With all of this happening in as little as 10 hours, it doesn’t give you much time to fix the problem.

Botflies like to get under your skin, literally . They start by laying their eggs on mosquitos. What do mosquitos like to do? Bite humans. This conveniently deposits the botfly eggs under our skin. They then hatch, and the larvae have a nice warm place to live.

Through a small hole in your skin, the larva can breathe. They feed on the flesh in their little skin cave and stay cozy and warm. Once they grow into bumblebee-sized adults, they crawl out to lay eggs somewhere else. If there are many larvae involved, it’s called myiasis, meaning an infestation under the skin. Yum. That’s why it pays to pack a good bug spray.

During the Cold War, the U.S. military ran thousands of training runs in the area of the Darién Gap, dropping bombs over the jungle. Most of the bombs detonated. However, some did not. Those bombs have been covered over by jungle growth and are now hidden on the jungle floor under a layer of vegetation. These remaining undetonated explosives still lie in the jungle, waiting for some poor, unfortunate soul to step off the trail — what little trail is there — just a bit too far and set off a massive explosion.

The Darién Gap is home to many predators, both human and animal, but one of the most deadly is the American crocodile. Crocodiles are apex predators, with no known natural enemies, and anything that they come in contact with is potential prey, including humans.

Crocodiles prefer to hunt at night, but they will attack and eat prey at any time. They hide in the water near the edge and wait for an unsuspecting animal (or unlucky hiker) to come to the water and then the crocodile strikes, dragging its prey down under the water to drown it.

So the Darién Gap sounds downright peachy to visit, doesn’t it?

Editors’ Recommendations

- The most popular Grand Canyon trail reopens this week

- These are the most incredible, picturesque mountain towns for a winter getaway

- There are actually 8 continents, and scientists have finally mapped the one that’s (mostly) hidden underwater

- The most and least visited National Parks: See popular sites (or avoid crowds)

- Tackle the World’s Most Famous Peaks With The North Face 7 Summits Collection

- Destinations

The Sunshine State has long been synonymous with pristine beaches, vibrant nightlife, and, of course, world-class golfing experiences. Florida’s rich history with golf dates back to the late 19th century, when affluent northerners seeking respite from the harsh winters discovered the state’s beautiful climate and sprawling landscapes. As such, Florida naturally became a popular choice for golfing retreats. Its flat terrain, dotted with natural water hazards and framed by swaying palm trees, provided the perfect canvas for golf course architects to create masterpieces that only continue to grow in popularity.

Today, Florida boasts a wide array of golf resorts that cater to players of all skill levels. Let’s take a look at some of the best golf resorts in Florida, each offering fun golf experiences as well as luxury accommodations and gorgeous scenery. World Golf Village, St. Augustine

The van-life movement has evolved beyond short-term escape into a way of life in the most minimal and sustainable sense. Should you decide to spend days or weeks traversing the country on four wheels sounds appealing, then this one is for you. We’ve put together a starter kit of essential tips and gear — most of which is similar to any extended car camping trip.

Here’s everything you’ll need to stay safe, sane, and happy when living in your car (or truck or van) for a few weeks or even longer. Whether you're trying to fully embrace van life or just planning an extended road trip to get out of your house, here's the low-down on how to live in your car. Learn how to get a good night’s rest

- Fashion & Style

Running can be a lot of fun and certainly very healthy, but a lot of folks starting out tend to use pretty much any shoes without realizing that they're probably hurting themselves in the long run. Not all shoes can support running when it comes to wear and tear and overall comfort, as well as just support your feet as well to make sure you don't run into any health issues in the future. While buying a new pair of shoes may feel a bit wasteful in terms of money, there are quite a lot of great shoes that have deals on them, including some of the best men’s running shoes, so you have a ton of options, and we've collected some of our favorites below. Today’s best running shoe sales From clearance offers to seasonal deals, here's are all of the best running shoe deals we could find: Adidas -- Get up to 40% off

Adidas running shoes start from just $28 with up to 60% to be saved on many models. The cheapest pair is the Duramo SL running shoes and best for only occasional use, however, you can also invest in something like the 4DFWD 3 running shoes which are very well-regarded and down to $110 from $200. Different models are available so look to see if you need trail running shoes with extra support and waterproofing, or if a regular pair of road running shoes are best.

TOUR DE FRANCE

Don’t miss a moment with our daily newsletter.

THE TOUR DE FRANCE DAILY NEWSLETTER

A Terrifying Journey Through the World’s Most Dangerous Jungle

The Darién Gap is a lawless wilderness on the border of Colombia and Panama, teeming with everything from deadly snakes to antigovernment guerrillas. The region also sees a flow of migrants from Cuba, Africa, and Asia, whose desperation sends them on perilous journeys to the U.S. Jason Motlagh plunged in, risking robbery, kidnapping, and death to document one of the world’s most harrowing treks.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! >","name":"in-content-cta","type":"link"}}'>Download the app .

“H uelo chilingos,” the boatman shouts over the drone of an outboard motor. I smell migrants .

I turn around and see nothing but a wall of dark, unruly jungle, then I slump back into the bow of the canoe. Five days we’ve been out here, waiting for a group of foreigners to appear on this godforsaken smuggler’s route in the Darién Gap, and all we have to show for it is sunburn and trench foot. Our search is starting to feel futile.

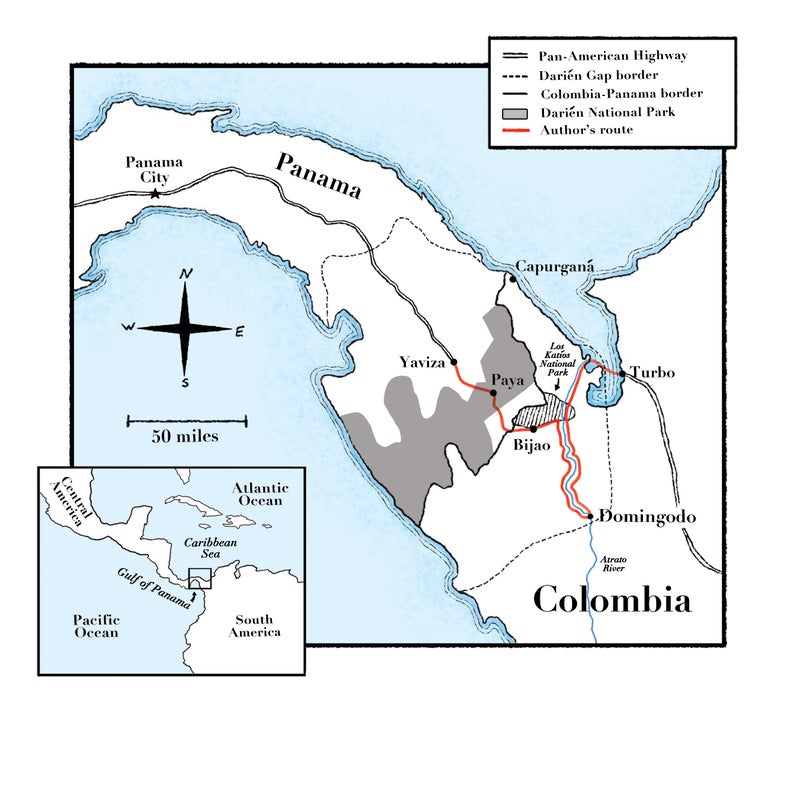

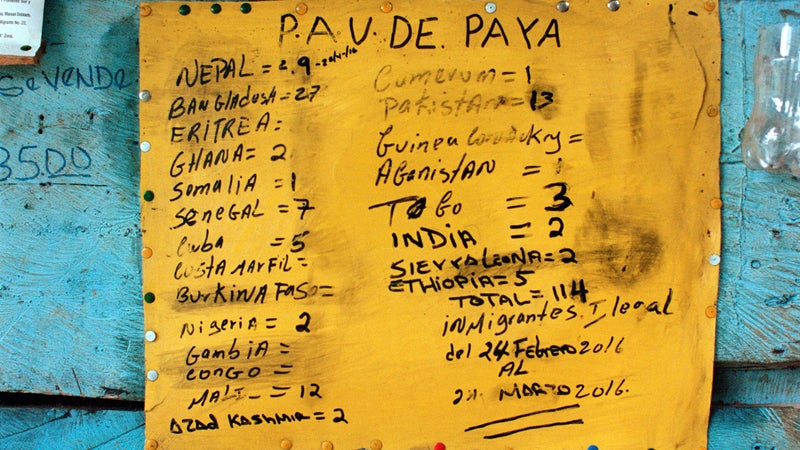

For centuries the lure of the unknown has attracted explorers, scientists, criminals, and other dubious characters to the Gap, a 10,000-square-mile rectangle of swamp, mountains, and rainforest that spans both sides of the border between Colombia and Panama. Plenty of things here can kill you, from venomous snakes to murderous outlaws who want your money and equipment. We’ve come to find the most improbable travelers imaginable: migrants who, by choice, are passing through the Darién region from all over the world, in a round-about bid to reach the United States and secure refugee status.

As traditional pathways to the U.S. become more difficult, Cubans, Somalis, Syrians, Bangladeshis, Nepalis, and many more have been heading to South American countries and traveling north, moving overland up the Central American isthmus. The worst part of this journey is through the Gap. The entire expanse, a roadless maze that travelers usually negotiate on foot and in boats, is dominated by narco traffickers and Cuba-backed guerrillas who’ve been waging war on the government of Colombia since 1964. Hundreds of migrants enter each year; many never emerge, killed or abandoned by coyotes (migrant smugglers) on ghost trails.

Our attempted trip is possible only because we’re traveling with the permission of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the Marxist rebels who control access to the most direct line through the Gap—an unmarked, 50-mile, south-to-north route that’s also used to move weapons and cocaine. Following months of negotiations, FARC commanders based in Havana have agreed to let us attempt the trek and visit a guerrilla camp, so long as we keep the main focus on migration, not politics. After five decades of fighting, at a cost of more than 220,000 lives on both sides, FARC and the Colombian government are in the final stages of a peace deal that would end Latin America’s longest-running insurgency. No more complications are needed.

Having spent the better part of a week idle in Bijao—a ramshackle hamlet on Colombia’s Cacarica River, which a group of migrants is said to be approaching—we’re restless. So today we traveled three hours by boat to visit FARC rebels on an adjoining waterway. An entire morning was spent hacking through spider-infested mangrove swamps to reach their camp, only to be told that our scheduled interview is off because they don’t have their uniforms with them.

Interview with the Author

We are on our way back to the village, cursing our bad luck, when the boatman repeats himself.

“Huelo chilingos.”

“Bullshit,” I sigh.

“No, man, he’s right—I think I saw an elbow,” says Carlos Villalon , a Chilean photojournalist who’s traveling with me. Carlos, 50, has a knack for busting my balls at the worst moments, but he’s already standing up, camera in hand. Roger Arnold, a 48-year-old videographer I met in Afghanistan, who’s along to film our trip for a TV newsmagazine in Australia, is poised right beside him.

We round a bend and there they are: two Bangladeshis, bent over, sloshing forward in waterlogged rubber boots. They give us a nervous grin, thumbs up. Twenty yards ahead of them, a big, shirtless Colombian coyote is towing a canoe that contains another half-dozen migrants. Several Nepalis slog alongside.

I catch up to explain that we’re journalists, but none of the men speak much English. Nor do they believe what I’m telling them.

When I ask Arafat, a 20-year-old construction worker from the Noakhali district in southern Bangladesh, if his goal is to reach the United States, he shakes his head. “No, no. Tourist, ” he says, patting his chest. “Problem?”

There’s no problem, I assure him as I approach the canoe, which is nearly scraping the bottom of the low-running river. Arafat’s friend Jafar leans back and laughs behind a pair of knockoff gold Ray-Bans. “Yeah, man!” he says. “Panama!” More thumbs up.

This tourist charade soon falls apart. A pudgy Bangladeshi man named Momir, his face ghoulishly pale from fever, rejects the coyote’s order to get out of the boat when it runs aground. Arafat shows us a large gash on the bottom of his foot and refuses to walk any farther. The men are weak from days of traveling in muggy, 90-degree temperatures, subsisting on crackers and gulping river water. And they are scared. For all they know, we’re Colombian authorities about to arrest them, or bush thugs ready to strip them of their remaining cash, stitched inside the lining of their pants.

The men are weak from days of traveling in muggy, 90-degree temperatures, subsisting on crackers and gulping river water. And they are scared. For all they know, we’re Colombian authorities about to arrest them, or bush thugs ready to strip them of their remaining cash.

Jafar starts to cry, triggering an outburst of desperate pleas from the men. They flash scars on their wrists and stomachs; one is missing part of a finger. “Bangladesh politics,” a man named Nazrul says ruefully as he drags a hand across his neck.

During a three-month stint reporting in Bangladesh in 2013, I became familiar with its cutthroat political gangs and dismal working conditions. Activists, journalists, and opposition members are often hacked to death in public. Rising water levels are drowning farmlands. Rural laborers flock to hyper-crowded cities for work and find themselves locked in the bowels of unlicensed garment factories, toiling for 20 cents an hour.

It’s easy to understand why any sane person would leave such grim prospects behind. Harder to grasp is how these men ended up on the southern edge of the Darién Gap, half a world away from home, without the faintest idea of the grueling trials ahead. Their willpower is amazing, but the Gap’s shadowy depths have swallowed travelers far more prepared. As we continue upriver together, it seems just as well that they are ignorant of the dangers.

The Pan-American Highway network is a remarkable feat of engineering that runs about 19,000 miles from Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, to Ushuaia, Argentina, with just one break in the pavement: the Darién Gap. Also known as El Tapón (“the plug”), it can’t be bypassed on land. It’s roughly 100 miles wide, stretching all the way from the Caribbean Sea to the Pacific Ocean. It has long defied the advance of colonists, road builders, and would-be developers.

The Gap’s legend as a black zone is steeped in bloodshed and tragedy. After Spanish conquistadors discovered the region in 1501, they consolidated their first mainland colony in the Americas by slaughtering tens of thousands of natives, often by turning ravenous dogs loose on villages. The Spanish conquered the Amazon and the Andes but eventually gave up on taming the Gap, which became a bastion for pirates and runaway slaves. In 1699, more than 2,000 Scottish colonists perished from malaria and starvation, and in 1854 nine explorers died from disease and exposure on a U.S. Navy survey expedition, scuttling plans for a grand canal project through the isthmus. In more recent times, efforts to build a road link have foundered because of fears that foot-and-mouth disease could spread and devastate the U.S. beef industry, and because of resistance from the Kuna and Embera-Wounaan Indians who inhabit the rainforest.

The absence of any controlling authority in this wilderness has given free rein to armed groups. A military branch of FARC known as the 57th Front calls the shots around much of Colombia’s Chocó Department—a dirt-poor sliver of land in northwestern Colombia that overlaps the Gap and is one of the wettest places on earth—and often moves freely back and forth across the porous border with Panama, a vital transit area for arms shipments and the cocaine exports that fund its war chests.

In the early years of Colombia’s civil conflict, adventurers could still move through the Gap by foot, motorbike, or four-wheeler. The first vehicular crossing was achieved in 1960 by a Jeep and Land Rover expedition, at an average speed of 220 yards per hour over 136 days. George Meegan of England went even farther, getting shot at in the Gap during an unbroken trek across the Western Hemisphere that he started in 1977. In the eighties, a British adventure travel company offered multiweek treks through the Gap. But by the mid-nineties, the prevalence of armed groups led to a plague of kidnappings, disappearances, and murders that put an end to such trips.

In 2000, two Brits, Tom Hart Dyke and Paul Winder, were taken hostage by FARC guerrillas while searching for rare orchids. They were held for nine months and threatened with execution before being released unharmed. In 2003, Robert Young Pelton, author of The World’s Most Dangerous Places , and two backpackers were held for more than a week by the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC), the formally demobilized right-wing militia that was once the largest paramilitary group in the country. In 2013, Jan Philip Braunisch, a Swedish traveler attempting to cross the Gap alone via the Cacarica River—our planned route—vanished in FARC territory. It later emerged that he was killed by a shot to the head.

Since the late aughts, U.S. authorities say, FARC has increasingly relied on the Darién corridor to smuggle drugs north as traditional air and sea routes have been clipped. Fierce competition for massive drug profits has also fueled the rise of neo-paramilitary groups that terrorize the region with wanton killings and armed assaults. The most powerful is the Clan Úsuga, a.k.a. Los Urabeños, a vicious gang made up of ex-AUC members. Seizing control of lucrative routes along the Caribbean coast, Los Urabeños has used its links with Mexico’s Sinaloa cartel to expand its presence around the country and challenge FARC in parts of Chocó.

When migrants began turning up near the border, both groups started using well-worn drug-smuggling routes to move human traffic for money. Over the past ten years, this flow has swelled to a steady stream as the standard maneuvers for reaching or rooting in the U.S., like overstaying a visa, have become tougher to execute. Cubans, lured by the promise of political asylum upon hitting American soil, account for most of the migrant flow, preferring the lesser known path through Central America to the familiar perils of the Florida Straits. But they are rivaled by a rising tide of Haitians, Somalis, West Africans, and South Asians.

Though it’s impossible to know the precise numbers, Panama saw 25,000 illegal arrivals last year, more than three times the number that came through in 2014. (Of these, about 20,300 were Cubans.) By late May of this year, another 8,000 migrants had passed through the Gap.

The fact that so many people would undertake such a long-shot journey caught my eye and Carlos’s well before we knew each other. Back in 2006, he was reading a newspaper in Bogotá when he saw a story buried in the back pages: a boatload of Chinese migrants had been captured in the Gap. During one of the half-dozen trips Carlos has since made in the region, he came upon the decomposing body of a Cuban migrant on a jungle trail. On another, he was stunned to pass a boat full of Somalis and Bangladeshis on the Cacarica. Smugglers ultimately turned him back, but the incongruous scene lingered in his head.

An article in The Wall Street Journal last year had the same effect on me. It described how growing numbers of U.S.-bound migrants are flying or taking cargo vessels to Brazil and Ecuador, countries with lax visa and asylum requirements, then heading overland to Colombia on backcountry buses. Those with the means and a passport hire boats to bypass the jungle and reach Panama by sea; the rest take their chances running the Gap. In Panama they’re detained for background checks. So long as their names don’t turn up on international terror watch lists—which I was told has never happened—they are released to keep heading north.

These migrants are a fraction of the more than 65 million people that the United Nations estimates are now in flight because of war, persecution, and terror, the largest such displacement in human history. There are refugees in peril all over the world: Syrians seeking safe haven in Turkey, West Africans traversing the Sahara en route to Europe. But the Darién Gap is the global migration story in extremis. What could possibly possess someone to enter it?

The Gap’s legend as a black zone is steeped in bloodshed and tragedy. After Spanish conquistadors discovered the region in 1501, they consolidated their first mainland colony by slaughtering tens of thousands of natives, often by turning ravenous dogs loose on villages.

By land or sea, the main jumping-off point for crossings into Panama is Turbo, a dodgy Colombian port town on the Gulf of Urabá that has a bad reputation for violence. Once a FARC stronghold, Turbo became a battleground in the late 1980s when paramilitaries took over. We had been scheduled to travel there in early April, but we had to delay when Los Urabeños, excluded from peace talks with the government, called for a 24-hour strike to show that it still runs this part of the country. All public transport and shops shut down; streets emptied. Three policemen and an army captain were shot dead, presumably after the gang announced a reward for killing authorities. A group of traffic cops were injured by a grenade.

A month later, on May 6, we checked in at our residencia on a balmy morning. From a balcony overlooking a shaded plaza that has hosted many a drunken machete fight, I watched fishermen mend their nets while others played cards. Horse-drawn flatbed trailers bearing grains and bananas—the region’s chief legal cash crop—whipped by in a flurry of hooves. Turbo, the northern terminus of the Pan-American Highway in South America, is home primarily to darker-skinned Afro-Colombians, descendants of slaves brought to work in agriculture and mining in the 1500s. I didn’t see any migrants among them.

Lying in a hammock, with two German shepherds nestled at his feet, the motel’s manager, Juan Montero, explained that Urabeño smugglers usually charge between $500 and $700 to shuttle a migrant from here to Panama, a five-hour trip in a leaky boat. Alternatively, some migrants opt for a harder, cheaper inland route that starts at the coastal town of Capurganá or Sapzurro and goes through a series of hamlets that dot Darién National Park, which covers a large part of the central and west side of the Gap. Because there is no Colombian border facility nearby where captured migrants could be sent, Panamanian authorities have typically allowed them to pass.

One week before our arrival, however, the immigration office in Turbo began granting migrants exit papers to bring the traffic aboveground. Now they could openly buy boat tickets to Capurganá and Sapzurro. From there it’s a short boat connection or hike to La Miel, in Panama. Those without documentation might still hire coyotes to take them up the longer jungle route, which is also a major Urabeño drug-trafficking path. The gang is known to forcibly conscript migrants as mules—and sometimes dispose of them.

At a moss-cloaked graveyard on the edge of Turbo, several tombs were scrawled with “N.N.” (no name), in drab contrast to the colorful encomiums locals left for loved ones. Montero told me that most of the dead were Somalis who had been robbed and tossed overboard by ruthless coyotes. On a 2014 trip to Acandí, an Urabeño-dominated town across the gulf from Turbo, Carlos had photographed the tomb of Roberto Tremble, a 33-year-old Cuban murdered by smugglers.

Cubans still accounted for most of the migrants, Montero said. “Many doctors,” he noted. Until recently, they flew to Ecuador, one of the few countries that have no visa requirement for tourist stays. But Ecuador had changed its policy, and Cubans were now coming in waves from Guyana, which was their last legal beachhead in South America.

In a video shot on Montero’s smartphone, Miguel, a ropy old Habanero, touted Cuba’s free health care and education but grumbled that his salary was not enough to buy shoes. “We are a country bounded by water and we don’t have enough fish for the people,” he fumed. “Populist socialism is terrible.”

Another Montero video showed a group of Nepalis hunched over paper plates in the same room we were now in. Authorities had caught them and brought them to Montero’s for a meal before deportation. “Of course, I never called customs on any of the ones who stayed here, because I don’t agree that those looking for a better life should be sent back,” Montero said. “Their motivation is incredible.”

Montero’s place was currently empty of migrants, so he directed us to the Hotel Goodnight, a flophouse located several blocks away, past bars and pool halls full of guys who threw us bloodshot stares. In the second-floor lobby, I found two Haitian teenagers thumbing WhatsApp on their phones. I introduced myself. One immediately exited down the hallway; the other refused to look up.

A third man was smoking on the balcony. He told me his name was Jackson Wilner and that he was a mason from Cap Haitien looking for work in Turbo. When I pressed him on how he planned to get to Panama, he stuck to his script. On my way out, I noticed that the door to his room was ajar. Looking in, I saw four people lying on a single bed. Three more were asleep on the floor.

Before dawn the next morning, we headed down to the docks. A boat was leaving for Capurganá, and Montero was sure it would draw migrants into the open. He was right. In the dim light, I could see men milling around. They turned out to be Haitians, Nepalis, and Pakistanis.

Zia ul-Haq, who I talked to on the dock, was the lone Afghan in the group. Twenty-six and slender, with thick brows hanging over forlorn eyes, he told me in halting English that he learned the language by watching bootleg DVDs: the Fast and Furious series was a favorite. He hailed from Nuristan, a remote, beautiful, and violent pocket of mountain ridges plied by fierce tribesmen. Zia’s uncle worked as a translator for U.S. forces, and the family moved to Kabul when Taliban death threats intensified. His uncle was eventually relocated to the United States. Zia applied twice for a visa to follow him, without luck. “Day by day it was getting worse, so I took this journey,” he said. “If someone’s life is in danger, they will do everything for themselves.”

Dubai. São Paulo and the Brazilian Amazon. Peru. Ecuador. Colombia. For the past two weeks, Zia had been dodging police shakedowns, riding back roads in chicken trucks, slipping across borders after dark. From here he would head by boat to Capurganá and then Panama or walk through the jungle; he’d heard the hike was anywhere from two to four days. He confessed to having no idea how to navigate the minefield of gangs, authorities, and six borders that would still lie between him and the U.S.