Moths Know Where to Go: A Look at Moth Migration

Moth migration may be guided by an internal compass to find the way, according to a new study that tracked flight paths of individual moths.

By Vaishnavi Sridhar

Just like we may take an annual vacation, every year countless animals, birds, and insects migrate seasonally. Many of these organisms travel very far each year. How do they know where to go? In the insect world, migration of butterflies is very well studied; however, not much is known about moth migration. Moths are related to butterflies , but most of them are active during the night. Every year many of these insects take a trip and most migrate at night. It is possible that many of us haven’t seen moths during migration. Maybe some moths you see in your garden have traveled a long distance to grace you with their presence!

Scientists held different views about moth migration throughout the 20th century. It was believed that moths controlled migration movement irrespective of wind in the first half of the 20th century. However, since there was no evidence in support of this, scientists in the second half of the 20th century believed that movement was largely controlled by the wind. Scientists currently think that migrating moths can adapt to wind conditions. In this study, researchers from institutions in Germany, the UK, Switzerland, and Australia studied the flight paths of moths and how they are affected by wind.

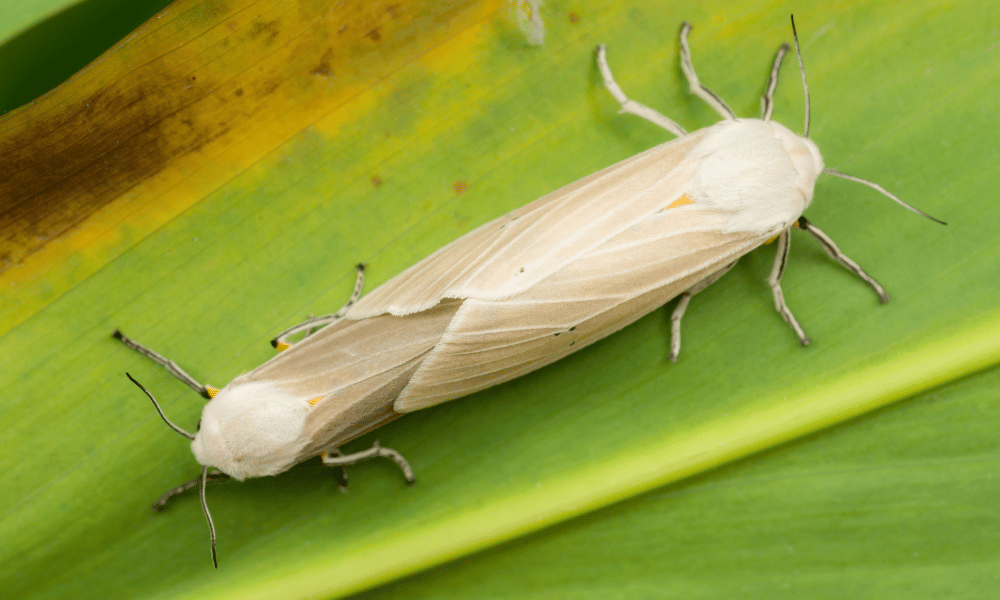

For this, Myles Menz and fellow researchers used the death’s-head hawkmoth (a large moth with skull-like markings). These moths arrive in Europe (north of the Alps) to breed each spring and the new generation of moths return to the Mediterranean and to sub-Saharan Africa in autumn. It was found that these moths can fly in a straight path irrespective of wind conditions. This means that they have an internal compass to orient themselves. This study adds to our knowledge about how insects migrate.

Moth migration: what is known so far

Even though a lot is known about the migration of a population of insects, not much is known about individual insects. Most insects migrate to breed, avoid predators, or avoid harsh weather. For example, European moths travel southward during autumn and northward during spring. It is also predicted that Australian bogong moths rely on Earth’s magnetic field and visual landmarks for migration. How moths navigate and maintain flight paths during migration has not been explored much. The main challenge has been mechanistic as it is hard to attach trackers onto such tiny organisms and track their flight paths at night for long distances. Studies to date have been unable to track individual moths.

New findings

In their study—published in the academic journal Science —Menz and fellow researchers set out to uncover how moths maintain flight paths over long distances and in response to environmental conditions. The death’s-head hawkmoths used in this study are large enough to take the weight of trackers. The researchers attached tiny trackers to the moths, and then complete tracks were recorded over a full night during seasonal autumn moth migration (from the Alps to the Mediterranean or sub-Saharan Africa). This gave information about how moths adjusted their flight paths as they migrated southward.

Researchers recorded fourteen moths in migration and detailed tracks of seven moths. Light aircrafts were used to record the information from the trackers. These aircrafts gave precise GPS location information in five- to fifteen-minute intervals. It was found that the moths started migrating at a similar time (after sunset) and the migration direction was south-southwest. This is very similar to other insects headed to the same destination, i.e., the Mediterranean or northwest Africa. Moreover, the speed of flight was recorded and was found to be similar to their known self-powered speed. This means that these moths either control their flight speed or hardly get assistance from the wind! Furthermore, moths maintained straight flight paths for tens of kilometers despite being subjected to varying wind speeds. In fact, two of the seven moths crossed the Alps in a single night.

Next, the researchers wanted to study how moths maintain their straight paths. For this, they calculated the angle between wind direction and the flight path taken by moths. It was found that moths employ three different strategies, which were partially influenced by ambient wind and topography (physical features of Earth). The first strategy was used when wind direction was unfavorable and moth migrations followed the most direct route by maintaining a constant southward track. The second and third strategies were used when wind direction was favorable. Scientists predicted that the favorable wind would aid the moths. However, it was found that moths can balance speed and direction by taking some assistance from the wind, but are not swayed completely.

This finding shows that these moths have an internal compass system that helps them maintain straight flight paths irrespective of wind conditions. Migrating hawkmoths have excellent night vision and could possibly use visual cues to navigate. When the straight moth migration travel paths were overlaid onto a map with physical features, it was found that moths avoid the highest elevations of the Alps, and might be using mountain passes and valleys instead.

This is the first study where moth migration flight paths have been tracked for a long distance. The researchers have elegantly demonstrated that moths can modify their flight paths in response to environmental conditions. It still needs to be determined what navigational cues these insects rely on. These results further show that insects can use complex means to maintain flight paths, giving an insight into insect migrations.

This research article was published in the peer-reviewed journal Science .

Menz, M. H. M., Scacco, M., Bürki-Spycher, H. M., Williams, H. J., Reynolds, D. R., Chapman, J. W., & Wikelski, M. (2022). Individual tracking reveals long-distance flight-path control in a nocturnally migrating moth. Science, 377 (6607), 764–768. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn1663

Chapman, J. W., Reynolds, D. R., Mouritsen, H., Hill, J. K., Riley, J. R., Sivell, D., Smith, A. D., & Woiwod, I. P. (2008). Wind selection and drift compensation optimize migratory pathways in a high-flying moth. Current Biology , 18 (7), 514–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2008.02.080

Dreyer, D., el Jundi, B., Kishkinev, D., Suchentrunk, C., Campostrini, L., Frost, B. J., Zechmeister, T., & Warrant, E. J. (2018). Evidence for a southward autumn migration of nocturnal noctuid moths in central Europe. The Journal of Experimental Biology , 221 (24), Article jeb179218. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.179218

About the Author

Vaishnavi Sridhar is a PhD candidate in Cell and Developmental Biology at the University of British Columbia. She loves discussing science, taking nature walks, and cooking in her free time.

Recommended for You

Caught in the Light: Flying Insects

Ant-ibiotics: How Ants Treat Infections

Do mosquito eaters eat mosquitos?

Animal Corner

Discover the many amazing animals that live on our planet.

Moths are insect closely related to butterflies. Both belong to the order Lepidoptera. The differences between butterflies and moths is more than just taxonomy. Scientists have identified some 200,000 species of moths world wide and suspect there may be as many as five times that amount.

Moth Description

Moths often have feather like antennae with no club at the end. When perched, their wings lay flat. Moths tend to have thick hairy bodies and more earth tone colored wings. Moths are usually active at night and rest during the day in a preferred wooded habitat.

Moths have very long proboscis, or tongues, which they use to suck nectar or other fluids. These proboscis are very tightly coiled not in use, like a hosepipe. When in use, the proboscis are uncoiled to their full length and in some species, that length is remarkably long. The Hummingbird Moth has a tongue that is actually longer than its whole body. The Darwin’s Hawk moth of Madagascar has a proboscis nearly 13 inches long, evolved, no doubt, to enable feeding on deep throated orchids which grow in that region.

Not all Moths have long tongues. In some, the proboscis is very short, an adaptation which enables easy and effective piercing of fruit.

In some, there is no feeding mechanism at all. There are adults of some species that do not take in any food. Their brief lives as an adult are spent reproducing and they are able to acquire all of the energy needed for this from the fat stored in the body by the caterpillar.

A moths antennae, palps, legs and many other parts of the body are studded with sense receptors that are used to smell. The sense of smell is used for finding food (usually flower nectar) and for finding mates (the female smelling the males pheromones). Pheromones can be dispersed through the tibia segment of the leg, scales on the wings or from the abdomen. Pheromones released by females can be detected by the males from as much as 8 kilometres away.

Moth Camouflage

Camouflage is a great defence in avoiding detection by a hungry predator. Some moths look just like lichen, others look exactly like the bark of trees native to their habitat. It has even been noticed that in city areas where smoke pollution is strong, some moths have actually developed a darker coloration than the same species that live in less polluted areas.

Another effective form of camouflage is coloration which can confuse a predator into either striking at a none vital part of the moths body or into missing it all together. The lines and spots on these moths would make aiming in on it difficult, especially when it is moving.

Another form of defence is where the moth takes on the appearance of a larger/or more threatening creature. This amazing ability is called ‘mimicry’. This form of defence ranges from caterpillars with tails that look like a large venomous snakes head, to moths and butterflies whose markings make them appear to be large birds.

Moth Vision

Moths (like many other adult insects) have compound eyes and simple eyes. These eyes are made up of many hexagonal lens/corneas which focus light from each part of the insects field of view onto a rhabdome (the equivalent of our retina). An optic nerve then carries this information to the insects brain. They see very differently from us. they can see ultraviolet rays (which are invisible to us).

The vision of Moths changes radically in their different stages of life .

Moth caterpillars can barely see at all. They have simple eyes (ocelli) which can only differentiate dark from light. They cannot form an image. They are composed of photoreceptors (light-sensitive cells) and pigments. Most caterpillars have a semi-circular ring of six ocelli on each side of the head.

Moth Senses

A caterpillars ‘fuzz’ gives it its sense of touch. Caterpillars sense touch using long hairs (called tactile setae) that grow through holes all over their hard exoskeleton. These hairs are attached to nerve cells and relay information about the touch to the insects brain.

Setae (sensory hairs) on the insects entire body (including the antennae) can feel the environment. They also give the insect information about the wind while it is flying.

Moth Navigation

Moths navigate by two methods. They use the moon and stars when available and geomagnetic clues when light sources are obscured.

Moth Behaviour

Moths heat up their flight muscles by vibrating their wings, since they do not have the radiant energy of the sun (being nocturnal) at their disposal to serve that purpose.

Other interesting facts about Moths

Night-blooming flowers usually depend on moths (or bats) for pollination, and artificial lighting can draw moths away from the flowers, affecting the plants ability to reproduce. A way to prevent this is to put a cloth or netting around the lamp. Another way is using a colored light bulb (preferably red). This will take the moths attention away from the light while still providing light to see by.

Despite being framed for eating clothing, most moth adults do not eat at all. Most like the Luna, Polyphemus, Atlas, Prometheus, Cercropia and other large moths do not have mouths. When they do eat, moths will drink nectar. Only one species of moth eat wool. The adults do not eat but the larvae will eat through wool clothing.

The study of Moths (and Butterflies) is known as ‘lepidoptery’, and biologists that specialise in either are called ‘lepidopterists’. As a pastime, watching Moths (and Butterflies) is known as ‘mothing’ and ‘butterflying’.

Moths, and particularly their caterpillars, are a major agricultural pest in many parts of the world. The caterpillar of the gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar) causes severe damage to forests in the northeast United States, where it is an invasive species. In temperate climates, the codling moth causes extensive damage, especially to fruit farms. In tropical and subtropical climates, the diamondback moth (Plutella xylostella) is perhaps the most serious pest of brassicaceous crops (the mustard family or cabbage family).

Butterflies and moths hear sounds through their wings.

Thousands of tiny scales and hairs cover moths wings, not powder.

Butterflies and moths both have an organ called the Johnston’s organ which is at the base of a butterfly or moths antennae. This organ are responsible for maintaining the butterflys sense of balance and orientation, especially during flight.

A Cecropia moth has the ability to smell his mate up to 7 miles away with his feathery antennae.

The Sphinx Hawk moth is the fastest moth in the world , capable of reaching speeds over 30 miles per hour.

More Fascinating Animals to Learn About

About joanne spencer.

I've always been passionate about animals which led me to a career in training and behaviour. As an animal professional I'm committed to improving relationships between people and animals to bring them more happiness.

The Moth Lifecycle

Moth metamorphosis includes four life stages: egg, larva, pupa and adult..

Shortly after mating, a single female moth will release a batch of eggs in clusters, ranging from a few dozen at a time, to more than 10,000. The eggs will then hatch into a larval moth (the “caterpillar”).

The period of time between “laying” and “hatching” varies considerably among species, with incubation times being as short as a few days, to as long as several months in instances where moths overwinter in egg-form. Descriptive and familiar names are often assigned to caterpillars such as wooly bears, hornworms or inchworms. In this lifecycle stage, most moth caterpillars feed on plant foliage.

Following the larva stage comes the pupa stage where the transformation to the adult form takes place. For moths, this often occurs within a silken case called a cocoon (butterflies form a different protective covering called a “chrysalis”).

For almost all moth species, adults have wings. Wings allow them to disperse, mate, and lay eggs, thus ensuring the legacy of their particular species. Depending on the geographic location, weather conditions, and species, some moths go through one generation per year whereas others may complete several, and a few even migrate during their lifecycle, similar to the well-documented migrations of the Monarch butterfly.

- Moth migration

- Identify a moth

- A-Z of moths

- #MothsMatter

- What are moths?

- Amazing moths

- Moths and climate change

- Moths in decline

- Finding moths

- Helping moths

- Occasionally troublesome moths

- The state of Britain's moths

- Moth recording

- National Moth Recording Scheme

- Gardening for moths

- Moth resources and downloads

- Moths Matter Campaign

- UK Moth Recorders' Meeting

- What’s Flying Tonight

Everyone is familiar with migratory birds flying into Britain, but did you know that moths migrate here too? Surprisingly for such flimsy looking insects, some of the moths commonly seen in our gardens may have travelled from places as far away as North Africa.

Although most of the moths found in Britain are resident here, passing through all the stages of their life-cycle within the UK, others come to our shores as migrants from continental Europe or further afield.

Some of the moths that arrive from other countries are species that already live here, so they are just adding to the resident population. However, most of the migrants that come to Britain and Ireland are species that do not live here permanently; they may breed here after their arrival, but their offspring do not survive our winter.

One spectacular migrant that is commonly seen every year is the wonderful Humming-bird Hawk-moth . It really does look like a little hummingbird as it hovers at flowers to feed on nectar. Amazingly, it comes to us all the way from the Mediterranean and even North Africa.

It arrives at any time from April to December, but numbers usually peak in August and September. Like all migrants, more are seen in hotter summers and when there are southerly winds. Some do breed here and it is possible that a few of the offspring now survive our milder winters.

Another very common migrant is the Silver Y , recognisable by the clear metallic Y shape on each forewing. This clever little moth has been tracked flying vertically upwards to hitch a lift on the faster high altitude winds! It is much smaller than the Humming-bird Hawk-moth, but newly arrived moths often behave in a similar way, hovering at flowers in the daytime to refuel after their journey.

The Silver Y breeds here in large numbers and the British-born offspring then add to the population, which can be very high by the end of the summer, but none (or very few) of these moths survive the winter.

Other notable migrants which are seen every year, although in small numbers, are the Death's-head Hawk-moth and the Convolvulus Hawk-moth , both with wing spans of about 12cm (five inches).

Some species, like the Crimson Specked, only occur in some years but may sometimes arrive in large numbers. Perhaps the most exotic looking migrant is the Oleander Hawk-moth , which only arrives in some years and even then in very low numbers.

Subscribe or renew today

Every print subscription comes with full digital access

Science News

Flying insects tell tales of long-distance migrations.

Well-timed travel ensures food and breeding opportunities

MASS MIGRATIONS This hawk moth ( Hyles gallii ) is one of millions of insects that migrate through a Swiss Alpine pass each year. Trillions of insects fly vast distances with the seasons to eat and breed. They may teach us something about how insects and other animals move around the planet.

Will hawkes, @Hawkes_Will

Share this:

By Alexandra Witze

April 5, 2018 at 6:00 am

Every autumn, a quiet mountain pass in the Swiss Alps turns into an insect superhighway. For a couple of months, the air thickens as millions of migrating flies, moths and butterflies make their way through a narrow opening in the mountains. For Myles Menz, it’s a front-row seat to one of the greatest movements in the animal kingdom.

Menz, an ecologist at the University of Bern in Switzerland, leads an international team of scientists who descend on the pass for a few months each year. By day, they switch on radar instruments and raise webbed nets to track and capture some of the insects buzzing south. At sunset, they break out drinks and snacks and wait for nocturnal life to arrive. That’s when they lure enormous furry moths from the sky into sampling nets, snagging them like salmon from a stream. “I love it up there,” Menz says.

He loves the scenery and the science. This pass, known as the Col de Bretolet, is an iconic field site among European ecologists. For decades, ornithologists have tracked birds migrating through . Menz is doing the same kind of tracking, but this time, he’s after the insects on which the birds feast.

Migrating insects, like those that zip through the Swiss mountain pass, provide crucial ecosystem services. They pollinate crops and wild plants and gobble agricultural pests.

“Trillions of insects around the world migrate every year, and we’re just beginning to understand their connections to ecosystems and human life,” says Dara Satterfield, an ecologist at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

Scientists like Menz are fanning out across the globe to track butterflies, moths, hoverflies and other insects on their great journeys. Among the new discoveries: Painted lady butterflies time their round trips between Africa and Europe to coincide within days of their favorite flowers’ first blossoms. Hoverflies navigate unerringly across Europe for more than 100 kilometers per day, chowing down on aphids that suck the juice out of greening shoots. What’s more, some agricultural pests that ravage crops in Texas and other U.S. farmlands are now visible using ordinary weather radar, giving farmers a better chance of fighting off the pests.

Until now, most studies of animal migration have focused on large, easy-to-study birds and mammals. But entomologists say that insects can also illuminate the phenomenon of mass movement. “How are these animals finding their way across such large scales? Why do they do it?” asks Menz. “It’s really quite fantastic.”

To warmer worlds

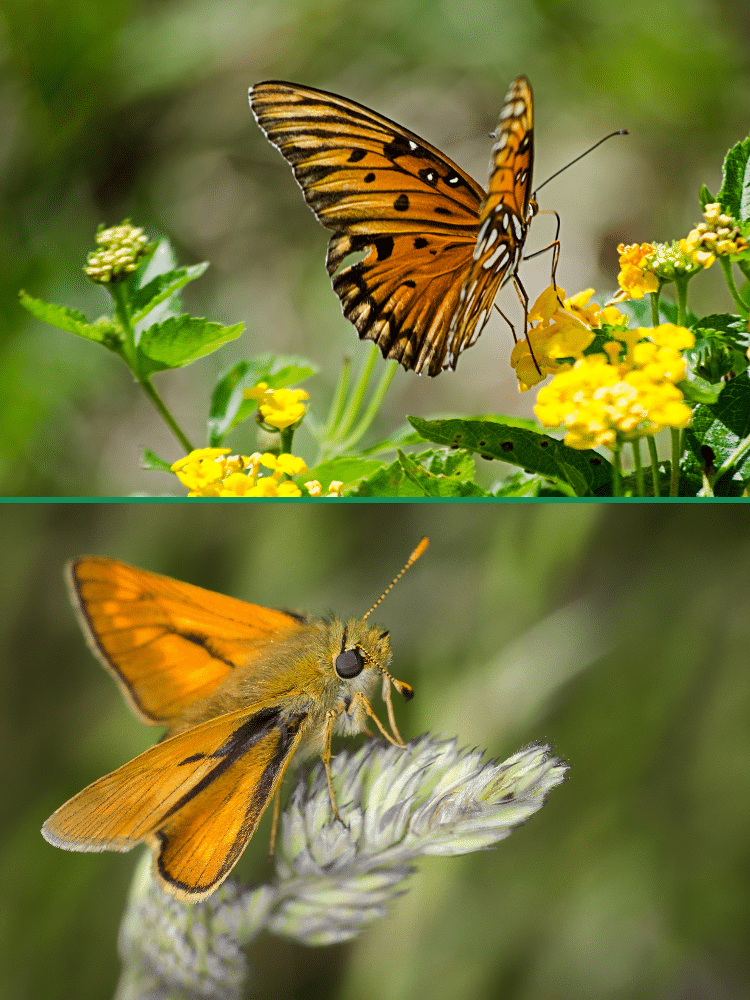

Animals migrate for many reasons, but the aim is usually to eat, breed or otherwise survive year-round. One of the most famous insect migrations, of North America’s monarch butterflies ( Danaus plexippus ), happens when the animals fly south from eastern North America to overwinter in Mexico’s warmer setting. (A second population from western North America overwinters in California.) In Taiwan, the purple crow butterfly ( Euploea tulliolus ) migrates south from northern and central parts of the island to the warmer Maolin scenic area every winter, where the butterfly masses draw crowds of lepidopteran-loving tourists. In Australia, the bogong moth ( Agrotis infusa ) escapes the hot and dry summer of the country’s eastern parts by traveling in the billions to cool mountain caves in the southeast.

The migrations can be arduous. Each spring, the painted lady butterfly ( Vanessa cardui ) moves out of northern Africa into Europe, crossing the harsh Sahara and then the Mediterranean Sea before retracing the route in the autumn ( SN Online: 10/12/16 ). Because adult life spans are only about a month, the journey is a family affair: Up to six generations are needed to make the round trip. It’s like running a relay race, with successive generations of butterflies passing the baton across thousands of kilometers.

Constantí Stefanescu, a butterfly expert at the Museum of Natural Sciences in Granollers, Spain, has been tracking the painted lady migrations. He relies on citizen scientists who alert him when the orange-and-black-winged painted ladies arrive in people’s backyards each year, as well as field studies by groups of scientists. In 2014, 2015 and 2016, Stefanescu led autumn expeditions to Morocco and Algeria to try to catch the return of the painted ladies to their wintering grounds.

By surveying swaths of North Africa, Stefanescu’s team confirmed that the painted ladies virtually disappeared from the area during the hot summer months and returned in huge numbers in October. The fliers arrived back in Africa just in time to feed on the daisylike false yellowhead ( Dittrichia viscosa ) and other flowers. The findings make clear how well the butterflies are able to time their migrations to take advantage of resources, Stefanescu reported in December in Ecological Entomology.

Painted lady butterflies embark on one of the world’s most distinctive migrations, traveling thousands of kilometers from Africa into Europe each spring, and back again in the fall. It can take six generations of butterflies to make the round trip journey.

Other insect species are less visibly stunning than the painted lady, but just as important to the study of migrations. One emerging model species is the marmalade hoverfly ( Episyrphus balteatus ), which migrates from northern to southern Europe and back each year.

Marmalade hoverflies have translucent wings and an orange-and-black striped body. As larvae, they eat aphids that would otherwise damage crops. As adults, the traveling hoverflies help pollinate plants. “They’re useful for so many things,” says Karl Wotton, a geneticist at the University of Exeter in England.

Wotton started thinking about the importance of insect migration after 2011, when windblown midges carried an exotic virus into the southern United Kingdom that caused birth defects in cattle on his family’s farm. Intrigued, Wotton set up camp at a spot in the Pyrenees at the border of Spain and France to study migrating hoverflies. Then he heard that Menz was doing almost exactly the same kind of research at the Col de Bretolet and a neighboring pass. The two connected, hit it off and now collaborate in both the Pyrenees and the Alps.

Funneled by the high mountain topography, hoverflies whiz through the passes like rush hour commuters through a railway station. “We’re talking about an immense number of insects,” Menz says. Millions of flies traverse the Swiss passes each year. Extrapolating to all of Europe, Wootton estimates that many billions of hoverflies are probably migrating. The insects consume billions of aphids that otherwise would have feasted on agricultural crops.

As astonishing as this migration is, most people never notice it. Only at the passes do the hoverflies become noticeable, a never-ending stream of tiny bodies glinting in the mountain light. They ride high on tailwinds and scoot low when the wind is against them. “They fly fast and low and they don’t stop,” Wotton says. “The butterflies are getting turned around like in a tumble dryer, but the hoverflies just shoot straight over.”

Wotton, Menz and colleagues use specialized upward-looking radar to track signals reflecting off of insects passing overhead. The researchers also use traps to catch individual flies to identify the species passing through.

Season after season, the researchers are building up a hoverfly census. By comparing that information with a 1960s survey done at the Col de Bretolet, the team hopes to determine whether species’ numbers have changed over time. Menz says: “I wouldn’t be surprised if they’ve declined.”

Other entomologists have documented sharp drops in the numbers of insects across Europe. In October 2017, a Dutch-German-British research team reported in PLOS ONE that the total insect biomass collected at 63 nature-protection areas in Germany over 27 years had dropped by more than 76 percent .

The paper garnered media headlines around the world as heralding an “ insect Armageddon .” That may be overly dramatic. The work covered just one small part of Europe, and the authors could not explain what might be causing the drop, whether climate change, habitat destruction or something else. But if hoverfly numbers are dropping, that would mean fewer are around to eat destructive aphids and to spread beneficial pollen. Hoverflies, which pollinate a wide range of plants, are the second most important group of pollinators in Europe after bees, Wotton says.

Drop in insect biomass collected in protected areas in Germany from 1989 to 2016

Hoverflies also migrate in North America, in ways that are far less understood than in Europe. This month, Menz and Wotton are visiting Montaña de Oro State Park on California’s Central Coast, where last year an entomologist reported spotting a rare hoverfly migration . The researchers hope to see whether the American hoverflies, probably a different species, are moving in the same ways their European cousins do.

Swoop in the destroyers

Not all migrating insects are beneficial. Some are troublemakers that chase ripening crops with the season. Farmers can spray pesticides once insects arrive in the fields, but knowing more about when and where to expect the critters can help growers better prepare for the onslaught.

Weather radar — Doppler data that meteorologists use to follow rain, hail and snow in near real time — is beginning to help. The radar signals reflect off of birds and other animals flying through the air. And although many insect species are too small to be detected in Doppler radar data, researchers are finding new ways to extract the signals of insects and track their migrations as they happen.

John Westbrook, a research meteorologist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service in College Station, Texas, has been using weather radar to follow insect flyways in the south-central United States. A 1995 outbreak of two migratory moth species — beet armyworm ( Spodoptera exigua ) and cabbage looper ( Trichoplusia ni ) — devastated cotton crops in Texas’ Lower Rio Grande Valley. Westbrook recently dug through the Doppler data from 1995 and was able to pick out the signals of these two species moving during the outbreak, Westbrook and USDA colleague Ritchie Eyster wrote in November 2017 in Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment .

Tracking pests

Weather radar data from southern Texas reveal the higher reflectivity of flying crop-eating moths (red). During an outbreak in 1995 that destroyed cotton crops, the moths flew northwest across much of Willacy County (shown) in under an hour. Farmers could use similar radar data to track pests approaching fields.

“Outbreaks are unpredictable,” Westbrook says. “But the weather radar can show where they are occurring.” Modern weather radar contains even more information than 1995 systems did, he notes — and farmers can use that data to their advantage. They may decide to spray heavily where most of the insects are gathering before they spread. Or farmers might stock up on pesticides if a particularly dangerous outbreak is headed in their direction.

Another way to track destructive insects is to grind them up and test the chemistry of their tissues. As caterpillars grow, they take on a characteristic chemical signature of the environment, with hydrogen, oxygen and other elements fixed in tissues in varying amounts. Analyzing those ratios can reveal the geographic region of a caterpillar’s origin.

Keith Hobson of Western University in London, Canada, and colleagues have been studying the insect pest known as the true armyworm moth ( Mythimna unipuncta ). It travels between Canada and the southern United States every year, damaging crops along the way. But scientists weren’t sure exactly where the insects originated each year, making it harder to figure out how to manage the problem with pesticides.

In new experiments, Hobson’s team captured true armyworm moths in Ontario throughout the year and analyzed the hydrogen retained within the moths’ wings. Moths captured early in the season had values similar to those seen in Texas waters, while those captured in the summer showed values closer to Canadian waters. The reverse was also true: Adult moths captured in autumn in Texas had Canadian-type values.

It is the first direct evidence that individual moths are making these long-distance round trips , the scientists wrote in January in Ecological Entomology. Further studies could reveal how to better control the pests throughout the growing season, by showing precisely where the insects are coming from and how far they will travel.

Larvae of the migratory cabbage looper (top) destroy cabbage and other crops. Alton N. Sparks, Jr., Univ. of Georgia, United States/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 3.0); Univ. of Minnesota. The migrating masses

For Menz, Wotton, Satterfield and the rest, the ultimate goal is to go from studying individual species to investigating broader questions of how and why animals move around. That includes exploring how insects alter food webs during migrations across the landscape.

For instance, Mexican free-tailed bats ( Tadarida brasiliensis ) in Texas and Mexico forage for nocturnal moths, which migrate in very narrow layers in the atmosphere based on how the wind is blowing. “These are like food webs in the sky,” says Jason Chapman, an ecologist at the University of Exeter. “Can bats read the weather patterns and predict where the insects are going to be?”

Similarly, many dragonflies attempt to migrate 3,500 kilometers or more across the Indian Ocean from India to east Africa and back each year, breeding in temporary ponds created by monsoon rains. The dragonfly-eating Amur falcon ( Falco amurensis ) makes a similar journey, in one of the longest-known migrations for any raptor. If the dragonflies are the reason for the falcon migration, then tiny insects are a major player in this important bird movement.

Insects rule the migratory world by virtue of their sheer numbers. Compared with birds, mammals and other migratory animals, insects are by far the most numerous. Roughly 3.5 trillion migrate each year over just the southern United Kingdom , a 2016 radar study suggested ( SN: 2/4/17, p. 12 ). That means that the majority of land migrations are made by insects .

To Aislinn Pearson, an entomologist at Rothamsted Research in Harpenden, England, studying insects will boost scientific understanding of how animals flow around the planet. “In the next 10 years,” she says, “a lot of the key findings of migration are going to come from these tiny little animals.”

This story appears in the April 14, 2018 issue of Science News with the headline, “Mass migrations: Researchers are asking big questions about animal movements by tracking tiny insects in flight.”

More Stories from Science News on Animals

Traces of bird flu are showing up in cow milk. Here’s what to know

Noise pollution can harm birds even before they hatch

Glowing octocorals have been around for at least 540 million years

A new road map shows how to prevent pandemics

Hibernating bumblebee queens have a superpower: Surviving for days underwater

This newfound longhorn beetle species is unusually fluffy

50 years ago, scientists wondered how birds find their way home

In a first, these crab spiders appear to collaborate, creating camouflage

Subscribers, enter your e-mail address for full access to the Science News archives and digital editions.

Not a subscriber? Become one now .

Migrating Moths Can Travel As Fast As Songbirds

Birds beat moths in short sprints, but long distance is a different story

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)

Sarah Zielinski

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20110520102441SilverYWillowWarbler.jpg)

If you held a short race between a silver Y moth and a European songbird, the bird would win hands down. These birds, such as warblers, thrushes and flycatchers, can fly about three times as fast as the silver Y moth. But when it comes to long-distance migration, from northern Europe to the Mediterranean or sub-Saharan Africa and vice versa, the moths have no problems keeping up with the birds, say scientists in Sweden and the United Kingdom in a new study in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B .

The researchers tracked silver Y moths in England and songbirds in Sweden during their nocturnal spring and fall migrations from 1999 to 2008, using a special kind of radar. They found that although the birds' airspeed was about three times faster than the moths', the two groups speed over the ground was about the same, ranging from 18 to 40 miles per hour.

"We had assumed that songbirds would travel must faster over the same distance," said study co-author Jason Chapman, of Rothamsted Research in the United Kingdom. "It was a great surprised when we found out the degree of overlap between the travel speeds---the mean values are almost identical, which is really remarkable."

The moths and birds take different approaches when migrating over these long distances: The moths wait for a favorable tailwind, or seek out an altitude with the fastest air, to give them a push towards their final destination. The birds, however, aren't so picky and rely on their wings to get them where they need to go.

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)

Sarah Zielinski | | READ MORE

Sarah Zielinski is an award-winning science writer and editor. She is a contributing writer in science for Smithsonian.com and blogs at Wild Things, which appears on Science News.

Moths: Complete Nest Guide

The world of moths is a diversely fascinating and extensive realm of knowledge. This is why researchers and bug enthusiasts alike have been enamored with many aspects of a moth; from its colorful scales to its interactions with light. But where exactly do these bugs live? How do they find shelter from the cruel parts of nature?

Moths do not build typical nests. Adult moths fly around in search of food and mate. The caterpillars crawl about looking for food. In both stages, they take temporary shelter wherever it is convenient. The closest they come to nesting is when they lay eggs or accumulate as pupae in cocoons.

Despite not being as colonial as bees or wasps, many species of moths do gather in large numbers, particularly when they are in their larval stage. And some species can become a serious pest problem.

So, it is important to identify where and how these moth species gather and grow.

Do Moths Build Nests?

When you think about a nest for insects, your mind probably conjures up the image of a beehive. Or you might picture a subterranean structure where ants and termites typically live.

These places serve several functions. They provide shelter from harsh weather and predators as well as a safe place for breeding and raising offspring.

But moths do not build any such establishment.

This does not mean that moths live completely separate lives from one another. At different stages of their lives, depending on their needs, moths will come together and form a colony that will resemble something like a traditional nest.

Moths have four distinct phases in their entire life cycle. The most recognizable of these stages is the ADULT MOTH .

These are the flight-capable, colorfully scaled, creatures, you see hovering around street lamps or in the attic.

Adult moths do not live for a long time. And in that short time, their main objective is to find a suitable partner for mating, while finding food is a secondary objective for most species.

So, they do not require a nesting ground to store and share food.

You can spot multiple adult moths in the same place taking shelter or hovering around a light source. But that is mostly a temporary situation and they will happily go to a new place if it is more convenient.

After mating, the female adult moths will lay their eggs in any area that can provide shelter, usually many at a time.

The eggs will remain in a cluster, which may give the illusion that this is a moth’s nest.

But it is more an accumulation of hundreds of eggs rather than a compound structure.

From the eggs, CATERPILLARS will hatch and immediately search for food. They move slowly, do share the same birthplace, and look out for the same food. That’s why these caterpillars can be found in a group before they separate over time.

Now, some moths will build mobile cocoons during their larval stage. Examples of such moths include clothes moths, bagworms, brown tail moths. These moths will build a cocoon with an opening on top. This way the caterpillars can easily come out when they find food. The browntail moths also use this cocoon to shelter them from the winter.

When the caterpillars reach the PUPA STAGE , which is the stage prior to becoming an adult, they will attach these cocoons to a solid structure.

Inside the cocoon, the moths start their metamorphosis process as the entire structure remains stationary.

And it is during this stage that you can associate moths with a nest-like structure.

After all, a nest is any stationary establishment that provides its occupant with the necessary shelter.

So, if you ever see a moth’s nest anywhere, it is most likely the collective cocoons of numerous moth pupa transitioning to become adults.

Where Do Moths Nest?

Now you know that the only time moths will stay inside a nest-like structure is when they are caterpillars that are either looking for food or a safe place to complete metamorphosis. And caterpillars have one specific duty; eat as much as they can to have enough energy for their metamorphosis.

As such, you will commonly find their cocoons near places where food is readily available. Many moth caterpillars carry their cocoons with them. So, they can set up their base where they can get easy access to their food source.

Since different moths have different dietary needs, they also nest in accordingly.

Moths that can be found inside a human house are the pantry moth, carpet moth, etc. The pantry moth will infest food grains in the kitchen. Carpet and clothes moths will nest in the closet, where they can feed on clothing materials, furniture, etc.

They usually don’t enter the house from nature but from infested food and clothes. These moths spread fast under friendly conditions and can reach numerous populations.

You will recognize an infestation normally by detecting adult moths flying around.

One of our related topics: Where Do Moths Go During the Day? (And Why)

The moths living indoors feeding on our food or clothes are also happy finding shelter and nutrition in the attic. While meal moths are rarely seen there, it can be a paradise for the clothes moths when the stored clothes aren’t sealed.

The moths aren’t disturbed and can develop for a long time before being discovered. You should package your clothes safely and check the attic regularly for any pests.

Natural moths can use any entrance to your home to enter it and look for shelter and food. ( How Long Can a Moth Survive in a House? )

But these species do have a very short lifespan and normally can’t reproduce in human houses. Moths in your chimney can occur now and then but don’t pose any threat to your environment.

Nevertheless, you should check if these moths are domestic species. Having clothes or meal moths in any part of your home can become a serious problem and should be treated immediately.

Outside of human homes, wild moths will build their cocoons in trees or bushes. This way the caterpillars can come out very easily to feed on their preferred plant.

When the caterpillars get ready to enter their pupa stage, they will fix their cocoons to the underside of a leaf or twig. Occasionally, such cocoons can be found on the ground though it is rare.

Tent caterpillars deserve a particular mention in this regard. The caterpillars of these moths are extremely social, meaning they are almost always found in large colonies. They set up large silk tents on the branches of the trees they reside in. Hence, they are called tent caterpillars.

How Do Moth Nests Look Like?

The majority of moth caterpillars create their cocoon by spinning silk around themselves.

This shell of silk can take on various forms but they are almost invariably white.

The caterpillars can be seen crawling inside or outside of the cocoon. They roam outside when they are about to feed. Once they reach their pupa stage, they will remain dormant. They will shut off any opening on the cocoon and will stay this way until they reach full maturity.

The tent caterpillar is a good example of this nesting process. They have acquired their names from the tent-like nest they build on host trees. The size of the tents varies according to the size of the colony. You will see these nests hanging from the twigs or branches of the trees. Sometimes the nest may be attached to the trunk of the tree.

Occasionally, you may find a l arge collection of moth eggs and mistake it for a colony. In reality, this is no permanent nest. Moths will lay their eggs wherever they find ample shelter and easy access to food. Because the first thing the caterpillars will search for after hatching is food to sustain their rapid growth.

Typically, these eggs look like tiny pears or white orbs. The eggs are usually in a cluster.

But the size of an individual egg is rather small. It is only when a moth lays hundreds of eggs together do they become easily noticeable to the naked eye.

How to Eliminate Moth Nests?

While most moth species prefer the wilderness and avoid human interaction, some species do live among us. Species such as the clothes moth, the carpet moth, and the pantry moth can pose a serious threat of infestation, ruining fabrics and food products.

So, it is important to properly identify their infestation and take steps to eradicate them.

1. Clean the Infested Area

Household moths have a few common places for setting up base. The corner of the closet or the attic or the pantry are ideal places for them. So, if you suspect you have a moth infestation in your home, you need to clean the infected area thoroughly.

Vacuum the rugs and carpet to remove the larvae and pupa hiding there. Also, clean your closet and the pantry to destroy their eggs.

Remove everything that appears to be a nest or an element of the moth life cycle.

2. Remove the Food Source

Pantry moths gain entry into your home through infected food grains. Once populated, it is very difficult to separate the food from the moths. So, it is best to just remove the food source entirely from your house.

You can do the same for any furniture or rug that has been damaged by moths. These fabrics are the prime food source for carpet moths. So, by removing any such furniture, you immediately take out a lot of their population.

3. Apply Essential Oils

These ancient oils are used for many years and claim to have various effects. Some are also popular for repelling flying insects like moths.

The most popular ones are lavender, cedar oil, peppermint, and eucalyptus. Most of them don’t have real proof of effectiveness, but it is worth a try.

4. Use Green Pesticides

Before applying chemicals in your house you should always consider using non-toxic methods. After you identified your moth species you should seek some natural remedies and give them a chance to prove their effectiveness.

5. Spray Classical Insecticides (not recommended)

When all methods didn’t work out (and that is very very rare), you probably want to apply a classical insecticide. Those products are widely available but should always be applied as instructed.

You should also try to avoid any place where humans stay for quite a while (like your bedroom).

If you are still unsure how to get rid of moths it is best to call in a professional.

How to Prevent Moths from Nesting

First, you need to know how moths infiltrate homes. Carpet moths come through old furniture and rags. Pantry moths enter through infected food grains. So, removing these sources of entry is the best way to prevent a moth’s nest from growing in your home.

Avoid domestic moths:

- recheck endangered areas regularly

- avoid open food sources

- stored clothes should be sealed

- wash new clothes as hot as allowed

If you are concerned about natural moths you might remember that those insects usually don’t reproduce or nest inside your home. But you can avoid their appearance easily with some simple measures.

Avoid natural moths:

- use mosquito nets

- avoid open windows / doors (esp. in the night)

- avoid light sources

- remove food sources

Some moth species are more social than others but they all require some form of shelter. As such, they will build cocoons to provide a safe place for searching for food and to go through their transformation into colorful, adult moths.

These structures can accumulate and give the impression of a moth nest, but it doesn’t have the same purpose and character as a beehive.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Copyright © 2024 pestabc .com All rights reserved.

- Complete List of Animals

- Animals that start with A

- Animals that start with B

- Animals that start with C

- Animals that start with D

- Animals that start with E

- Animals that start with F

- Animals that start with G

- Animals that start with H

- Animals that start with I

- Animals that start with J

- Animals that start with K

- Animals that start with L

- Animals that start with M

- Animals that start with N

- Animals that start with O

- Animals that start with P

- Animals that start with Q

- Animals that start with R

- Animals that start with S

- Animals that start with T

- Animals that start with U

- Animals that start with V

- Animals that start with W

- Animals that start with X

- Animals that start with Y

- Animals that start with Z

- Parks and Zoos

- Saturniidae

- Actias luna

- Euarthropoda

- Lepidoptera

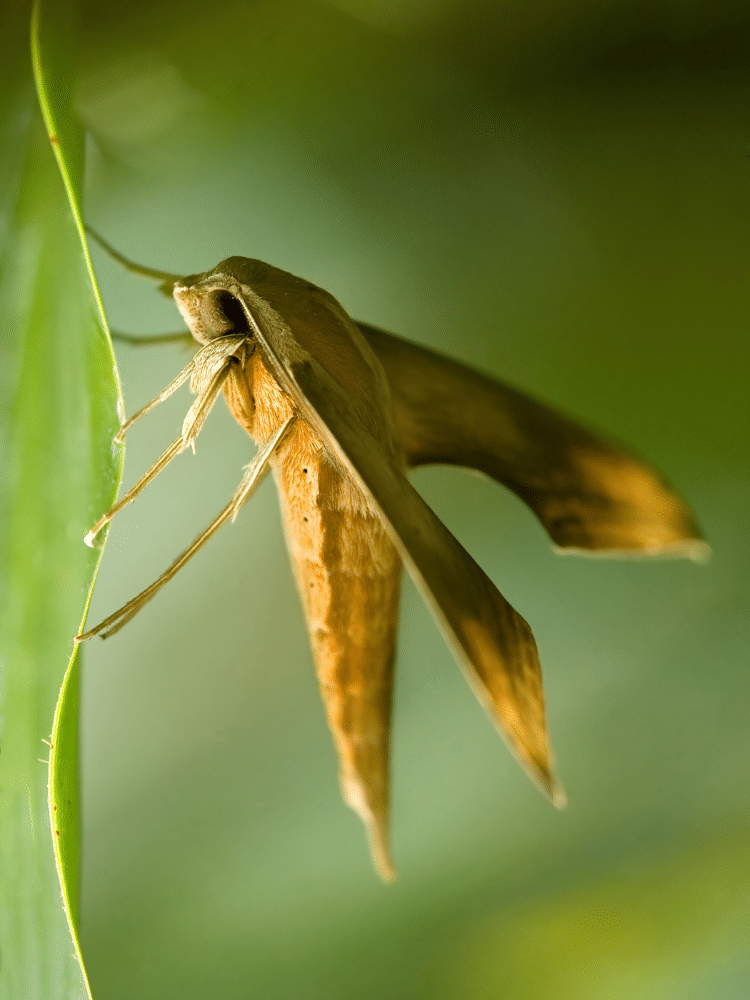

Luna moths are large, beautifully colored insects. They have bright green wings and white, fuzzy bodies. Their large wings have long “tails” that sprout from the base, giving them a unique, elegant appearance. Most Luna moths are about four or five inches across, but some specimens can be larger than seven inches! Read on to learn about the Luna moth .

Description of the Luna Moth

These insects are quite large, and some Luna moths can have a wingspan of seven inches or more. The wings are bright green in color, sometimes with a bluish tint, and sometimes with a yellowish tint.

The wings have two sections, the larger forewing, which is closer to the head; and the smaller hind wing, which is closer to the rear. Each wing has two eyespots, one on the forewing and one on the hind wing. The eyespots are oval shaped, and can be black, blue, white, green, red, or yellow.

Interesting Facts About the Luna Moth

These beautiful moths are actually incredibly interesting. They have a number of useful adaptations and odd traits.

- Eyespots – Like many moths and butterflies, Luna moths have eyespots on their wings. Eyespots are round marks on the wings that resemble eyes. Scientists believe these eyespots can confuse or deter predators, which may think the animal is larger than it actually is based on the size of the “eyes.”

- Wing Tail – Instead of having perfectly rounded wings, Luna moths have long protrusions that extend from each rear wing. In addition to their aesthetic appeal, these wing tails actually serve a purpose. Scientists believe the wing tails disrupt the echolocation of bats, one of the more skilled predators of Luna moths.

- Mouth Off – Even though, upon close inspection, you can see mouthparts on these moths, they serve no purpose. These mouthparts are vestigial, which means that they might have had use sometime in the past, but serve no purpose now. Once they evolve into the “adult” form, Luna moths do not feed.

- Luna Lifecycle – Like most butterflies and moths, this species undergoes metamorphosis to achieve its final shape. The female lays eggs, which hatch into larvae. These larvae will feed on leaves, and undergo five different molts as they grow larger. After their final molt, the larvae spins a cocoon out of silk and enters the pupae stage. Finally, after they transform in the pupae stage, the moth emerges as an imago , or its final adult form.

Habitat of the Luna Moth

These moths do not require a specific feeding area as an adult, because they do not eat! However, they will seek certain areas that house preferred species of plants when they lay their eggs.

In different regions Luna moths will prefer different plant species to lay their eggs on. The larvae will feed on white birch, hickory, sweet gum, persimmon, walnut, and sumac leaves. Not all larvae can feed on all of those plants, and some regions can only survive on a single species of plant.

Distribution of the Luna Moth

This moth species dwells only in North America. They live as far west as the Great Plains, and as far east as the coast of the Atlantic Ocean. In the United States one might find them from Maine, all the way down to Florida. In Canada, they live from Nova Scotia to Quebec and Saskatchewan. These moths live nowhere else in the world.

Diet of the Luna Moth

Adult Luna moths do not eat at all, as their mouthparts are non-functional. The only time these insects eat is during their larval stage. As discussed above, larvae from different regions will feed on different plants.

Some regions can feed on certain plants that larvae in other regions cannot, and vice versa. The plants regional larvae can eat are called host plants . Different host plants include persimmon, white birch, hickory, sumac, walnut, sweet gum, and more.

Luna Moth and Human Interaction

Luna moths and humans do not directly interact very frequently. Most human interactions occur when human-produced light sources attract moths. There are few negative interactions, as Luna moths do not conflict with humans in any way. This species is the only moth to appear on a United States postage stamp, and is generally regarded as a beautiful creature and not disliked by anyone.

Domestication

Humans have not domesticated Luna moths in any way.

Does the Luna Moth Make a Good Pet

Luna moths do not generally make good pets. Handling them can damage their wings, so they are a hands-off pet. You can raise the larvae if you know what type of host plant they require, but you should release the adult moth so it can reproduce with its own kind.

Luna Moth Care

In a zoological or household setting, these moths are simple to care for. The larvae require the right species of plant for feeding, and the adults do not feed at all. Because different regions have different host plants, it is important to do your research before attempting to keep Luna moth larvae. You can sometimes see them in butterfly habitats, but they do not feed on flowers.

Behavior of the Luna Moth

The behavior of this species is relatively simple. The eggs hatch, and the primary purpose of the larvae is to eat, and eat… and eat… and eat! Once they go through their pupae stage and emerge as an adult, the primary purpose of this insect is to reproduce. They no longer feed, and will release hormones to attract a mate. On average, the adult form lives only 7 – 10 days.

Reproduction of the Luna Moth

Male Luna moths have large antenna that help them detect the pheromones of females. The antennas are so impressive that they can detect a female from over a mile away. After mating, female moths lay between 200 and 400 eggs. She lays the eggs one by one, or in small groups, on the leaves of the preferred host plant. After about a week the eggs hatch, and the larvae begin eating.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

Mantis Shrimp

Expert Recommendations

Best Dog Puzzle Toys

Best Dog Beds

Best Dog Vitamins

Best Raw Dog Food

Best Dog Food for Small Dogs

Best Senior Dog Food

Best Outdoor Cat Houses

Best Dog Food for Sensitive Stomach

Best Dog Shampoo for Itchy Skin

Best Dog Boots

Even more news.

![Red Angus Closeup of a beautiful Red Angus cowPhoto by: U.S. Department of Agriculture [pubic domain]https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/](https://animals.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Red-Angus-4-100x75.jpg)

Paint Horse

House Spider

Popular category.

- Chordata 694

- Mammalia 247

- Dog Breeds 184

- Actinopterygii 121

- Reptilia 87

- Carnivora 72

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Science Notes Posts

- Contact Science Notes

- Todd Helmenstine Biography

- Anne Helmenstine Biography

- Free Printable Periodic Tables (PDF and PNG)

- Periodic Table Wallpapers

- Interactive Periodic Table

- Periodic Table Posters

- How to Grow Crystals

- Chemistry Projects

- Fire and Flames Projects

- Holiday Science

- Chemistry Problems With Answers

- Physics Problems

- Unit Conversion Example Problems

- Chemistry Worksheets

- Biology Worksheets

- Periodic Table Worksheets

- Physical Science Worksheets

- Science Lab Worksheets

- My Amazon Books

Why Are Moths Attracted to Light? Insect Phototaxis

The phrase “like a moth to a flame” refers to a potential fatal attraction, since a moth doesn’t always escape the heat of a fire or the zap of a bug light. But, why are moths and other insects attracted to light? There are several theories that explain the behavior. Which ones are correct?

- Moths and many other flying insects are attracted to light. This is called positive phototaxis . In contrast, some insects such as cockroaches avoid light. This is negative phototaxis .

- There are many theories about why moths are attracted to light. The transverse orientation theory has wide support from scientific studies. This theory proposes that light confuses insect navigation, causing them to circle the light as they maintain the same angle with respect to the light source.

- Regardless of the reason for the behavior, many flying insects feel attraction to light, heat, and electromagnetic fields.

Theories About Why Moths Are Attracted to Light

Phototactic behavior theory.

This theory proposes that moths are attracted to light or positively phototactic. The theory describes the behavior, but does not explain its reasons. It may be for navigation or predator evasion.

Laboratory experiment exposing moths to varying light intensities and wavelengths measure whether or not there are changes in their attraction levels. Moths and many flying insects, such as certain species of flies, move toward light sources or display positive phototaxis. Meanwhile, cockroach and some species of beetles display negative phototaxis and avoid light.

Transverse Orientation Theory

This theory proposes that rather than being attracted to light, moth navigation gets confused by it. Moths and many other flying insects use light for navigation. Light rays from a distant source (Sun, Moon, stars) are parallel to each other, so these insects have evolved to receive and process light in a transverse orientation. When a moth flies in a straight line, the visual pattern of a distant light remains constant. But, the angle of light rapidly changes for a small artificial light. So, keeping the angle constant results in the insect spiraling around the light.

Experiments testing this theory measure the angle of insect flight. Moths fly at a consistent angle around an artificial light, supporting the theory. In the case of moths, specifically, the insects keep their dorsal surface (back) toward the light. Another experiment tested whether moths navigate by maintaining a fixed position relative to celestial light. In this experiment, moth behavior changed when constellations in a planetarium were altered.

Fatal Attraction Theory

This theory suggested that artificial lights are so attractive to moths that they cannot resist them, even to the point of exhaustion or death.

Moths and certain other insects feel attraction to light, heat, and electromagnetic fields. While wind blows some insects out of their death spiral, the theory suggests flames and lights are irresistible. However, insects don’t land on hot light bulbs. One study showed that younger moths were attracted to lights, while older moths continued pollinating night-blooming plants despite the lure of artificial lighting. So, the fatal attraction theory is overly simplistic.

M isdirected Sexual Attraction Theory

Another theory proposes that insects confuse artificial lights with the infrared light frequencies of pheromones of potential mates. Two pieces of evidence largely disprove this theory. First, males feel attraction to female pheromones, yet both male and female moths are attracted to lights. Second, male moth sensory organs detect pheromones directly, without needing an infrared cue.

Ultraviolet Light Attraction

Another theory proposes that moths seek ultraviolet light as a pollination guide. Insects perceive ultraviolet light and some flowers have ultraviolet patches that guide pollinators. So, perhaps a light looks like a big field of blooms.

Research indicates ultraviolet, blue, and green lights do attract bugs more than yellow, amber, or red lights. This is true even for LED lights, which emit very little heat. But, whether this relates to insect pollination or simply reflects the way insect vision works is unclear.

Night Blindness

This theory proposes that insects remain circling lights for protection.

While humans recover from temporary blindness from bright outdoor lights pretty quickly, it takes insects around half an hour to recover their sight. So, they may stay within range of the light to avoid the dangers of flying blind, such as collisions and predators.

Pros and Cons of Moths Attracted to Light

Pest control.

Insect attraction to light has implications for pest control:

- Use of Light Traps : Light traps are common for controlling insects like moths. These traps efficiently capture large numbers of pests, reducing their impact on agriculture and horticulture.

- Targeted Pest Management : Understanding the specific wavelengths of light that attract certain pests leads to the development of more targeted and effective pest control methods, minimizing the use of chemical pesticides.

- Monitoring Pest Populations : Light traps are also useful for monitoring purposes, providing data on the types and numbers of species in a particular area. This information helps in implementing timely and appropriate pest control strategies.

Risks to Ecosystems from Light Pollution

However, there is a darker side to the insect attraction to light:

- Disruption of Natural Behaviors : Artificial light disrupt the natural behaviors of nocturnal insects, affecting their feeding, mating, and migration patterns. This disruption leads to declines in insect populations. This, in turn, affects species that rely on them for food, such as birds and bats.

- Altered Predator-Prey Dynamics : The unnatural concentration of insects around light sources alters predator-prey dynamics. Predators might exploit these gatherings for easy feeding, which further unbalancing ecological relationships.

- Impact on Plant-Pollinator Interactions : Many insects, including some moths, play a crucial role in pollinating plants. The disruption of their natural activity patterns due to artificial light impacts pollination of both wild and cultivated plants.

- Contribution to Insect Decline : Light pollution is one of the factors contributing to the global decline of insect populations. This decline has broader implications for biodiversity and the functioning of ecosystems.

- Behavioral Changes and Energy Expenditure : Exposure to artificial light leads to increased energy expenditure in insects as they navigate the illuminated environment, potentially reducing their overall fitness and survival rates.

- Boyes, D.H.; Evans, D. M. et al. (2020). “Is light pollution driving moth population declines? A review of causal mechanisms across the life cycle.” Insect Conservation and Diversity . 14(2): 167-187. doi: 10.1111/icad.12447

- Gorostiza, E.A.; Colomb, J.; Brembs, B. (2016). “A decision underlies phototaxis in an insect.” Open Biol . 6(12): 160229. doi: 10.1098/rsob.160229

- Jägerbrand, A.; Andersson, P.; et al. (2023). “Dose-effects in behavioural responses of moths to light in a controlled lab experiment.” Sci Rep . 13(1): 10339. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-37256-0

- Jonason, D.; Franzén, M.; Ranius, T. (2014). “Surveying Moths Using Light Traps: Effects of Weather and Time of Year.” PLoS ONE. 9(3): e92453. doi: doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0092453

- Suver, M.P.; Mamiya, A.; Dickinson, M.H. (2012). “Octopamine neurons mediate flight-induced modulation of visual processing in Drosophila.” Curr. Biol . 22: 2294–2302. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.034

Related Posts

Animal encyclopedia

Understanding the gypsy moth caterpillar.

Updated on: September 14, 2023

John Brooks

September 14, 2023 / Reading time: 6 minutes

Sophie Hodgson

We adhere to editorial integrity are independent and thus not for sale. The article may contain references to products of our partners. Here's an explanation of how we make money .

Why you can trust us

Wild Explained was founded in 2021 and has a long track record of helping people make smart decisions. We have built this reputation for many years by helping our readers with everyday questions and decisions. We have helped thousands of readers find answers.

Wild Explained follows an established editorial policy . Therefore, you can assume that your interests are our top priority. Our editorial team is composed of qualified professional editors and our articles are edited by subject matter experts who verify that our publications, are objective, independent and trustworthy.

Our content deals with topics that are particularly relevant to you as a recipient - we are always on the lookout for the best comparisons, tips and advice for you.

Editorial integrity

Wild Explained operates according to an established editorial policy . Therefore, you can be sure that your interests are our top priority. The authors of Wild Explained research independent content to help you with everyday problems and make purchasing decisions easier.

Our principles

Your trust is important to us. That is why we work independently. We want to provide our readers with objective information that keeps them fully informed. Therefore, we have set editorial standards based on our experience to ensure our desired quality. Editorial content is vetted by our journalists and editors to ensure our independence. We draw a clear line between our advertisers and editorial staff. Therefore, our specialist editorial team does not receive any direct remuneration from advertisers on our pages.

Editorial independence

You as a reader are the focus of our editorial work. The best advice for you - that is our greatest goal. We want to help you solve everyday problems and make the right decisions. To ensure that our editorial standards are not influenced by advertisers, we have established clear rules. Our authors do not receive any direct remuneration from the advertisers on our pages. You can therefore rely on the independence of our editorial team.

How we earn money

How can we earn money and stay independent, you ask? We'll show you. Our editors and experts have years of experience in researching and writing reader-oriented content. Our primary goal is to provide you, our reader, with added value and to assist you with your everyday questions and purchasing decisions. You are wondering how we make money and stay independent. We have the answers. Our experts, journalists and editors have been helping our readers with everyday questions and decisions for over many years. We constantly strive to provide our readers and consumers with the expert advice and tools they need to succeed throughout their life journey.

Wild Explained follows a strict editorial policy , so you can trust that our content is honest and independent. Our editors, journalists and reporters create independent and accurate content to help you make the right decisions. The content created by our editorial team is therefore objective, factual and not influenced by our advertisers.

We make it transparent how we can offer you high-quality content, competitive prices and useful tools by explaining how each comparison came about. This gives you the best possible assessment of the criteria used to compile the comparisons and what to look out for when reading them. Our comparisons are created independently of paid advertising.

Wild Explained is an independent, advertising-financed publisher and comparison service. We compare different products with each other based on various independent criteria.

If you click on one of these products and then buy something, for example, we may receive a commission from the respective provider. However, this does not make the product more expensive for you. We also do not receive any personal data from you, as we do not track you at all via cookies. The commission allows us to continue to offer our platform free of charge without having to compromise our independence.

Whether we get money or not has no influence on the order of the products in our comparisons, because we want to offer you the best possible content. Independent and always up to date. Although we strive to provide a wide range of offers, sometimes our products do not contain all information about all products or services available on the market. However, we do our best to improve our content for you every day.

Table of Contents

The Gypsy Moth Caterpillar is an intriguing insect that goes through several stages of growth and transformation. By understanding its life cycle, identifying features, diet, and threats, we can gain a deeper understanding of this remarkable creature.

The Life Cycle of the Gypsy Moth Caterpillar

Egg stage and hatching.

The life cycle of a Gypsy Moth Caterpillar begins with the egg stage. Female moths lay their eggs in masses, usually on the trunks or branches of trees. These egg masses are covered in a protective layer of hairs and scales.

During this stage, the female moth carefully selects the location for her eggs, ensuring that it provides the necessary protection and resources for the developing caterpillars. She uses her specialized ovipositor to attach the eggs to the chosen surface, ensuring their stability and survival.

After a couple of weeks, the eggs hatch, and hundreds of tiny caterpillars emerge. They may remain in the egg mass for a short time or disperse to find food. The hatching process is a remarkable sight, as the tiny caterpillars wriggle and push their way out of the eggs, ready to embark on their journey of growth and transformation.

Larval Stage: The Caterpillar

Once hatched, the Gypsy Moth Caterpillar enters its larval stage. During this phase, the caterpillar undergoes significant growth and feeds voraciously. Their body is covered in long, bristle-like hairs that vary in color from black to brown to yellow.

These caterpillars have five pairs of blue dots followed by six pairs of red dots on their back, which help in distinguishing them from other caterpillar species. These markings serve as a warning to potential predators, indicating that they are not suitable prey.

As the caterpillar grows, it sheds its outer skin multiple times in a process called molting. Each time it molts, the caterpillar reveals a larger and more vibrant body, ready to continue its journey towards adulthood. This growth is fueled by the caterpillar’s insatiable appetite, as it consumes vast amounts of leaves and other plant material.

Pupal Stage: The Transformation

After the larval stage, the Gypsy Moth Caterpillar enters the pupal stage. During this time, it constructs a cocoon using silk and surrounding materials such as leaves or bark. The caterpillar carefully weaves the silk threads, creating a sturdy and protective structure that will safeguard its transformation.

Within the pupal stage, the caterpillar’s body structures break down and reorganize, allowing the development of a fully-formed adult moth. This process is facilitated by the secretion of enzymes that dissolve the caterpillar’s tissues, making way for the formation of new structures.

Inside the cocoon, hidden from the outside world, the caterpillar undergoes a remarkable metamorphosis. Its organs and tissues rearrange and transform, while imaginal discs, small clusters of cells, develop into the intricate body parts of an adult moth. This transformation is a testament to the incredible adaptability and resilience of nature.

Adult Stage: The Moth

Once the transformation is complete, the adult Gypsy Moth emerges from the cocoon. The male moths are dark brown and have feathery antennae, while the female moths are larger and white. Both genders possess a wingspan of around 65 millimeters.

As adults, Gypsy Moths have a short lifespan, typically ranging from a few days to a couple of weeks. During this time, their primary focus is reproduction. The male moths use their feathery antennae to detect the pheromones released by the females, enabling them to locate potential mates.

After mating, the female moth will lay her eggs, starting the cycle anew. She carefully selects the ideal location, ensuring that her offspring will have the best chance of survival. The adult moths also play a crucial role in pollination, as they visit flowers in search of nectar, inadvertently transferring pollen from one flower to another.

The life cycle of the Gypsy Moth Caterpillar is a fascinating journey of growth, transformation, and adaptation. From the tiny eggs to the voracious caterpillars, and finally, the beautiful adult moths, each stage contributes to the intricate tapestry of nature’s wonders.

Identifying Features of the Gypsy Moth Caterpillar

Size and color.

The Gypsy Moth Caterpillar can vary in size, typically reaching about 2 inches in length. Their coloration can vary as well, depending on their development stage. Younger caterpillars tend to be black or dark brown, while older ones become more vibrant with yellow and red markings.

As the caterpillar grows, it undergoes a series of molts, shedding its old skin to accommodate its increasing size. During this process, the caterpillar’s coloration may change, revealing new patterns and hues. This transformation is not only a visual spectacle but also an important adaptation that allows the caterpillar to blend in with its surroundings and avoid predators.

Distinctive Markings

One of the key features that distinguishes the Gypsy Moth Caterpillar from other species is the presence of blue and red dots along their back. These markings are arranged in distinct patterns, making them easily recognizable to the trained eye.

These markings serve a purpose beyond mere aesthetics. They act as a warning signal to potential predators, indicating that the caterpillar is toxic or distasteful. This defense mechanism, known as aposematism, helps deter predators from preying on the caterpillar, increasing its chances of survival.

Habitat and Distribution

Gypsy Moth Caterpillars are native to Europe and Asia but have been introduced to various parts of North America. These caterpillars prefer hardwood trees, such as oaks and maples, but can also infest a wide range of other deciduous trees.

Their ability to thrive in diverse habitats has contributed to their rapid spread across different regions. In addition to their preference for hardwood trees, Gypsy Moth Caterpillars can adapt to various environmental conditions, allowing them to establish populations in both urban and rural areas.

Once the caterpillars find a suitable tree, they begin to feed voraciously on its leaves. Their appetite is insatiable, and a large infestation can lead to defoliation, weakening the tree and making it more susceptible to disease and other stressors.

Efforts to control Gypsy Moth Caterpillar populations have been implemented in affected areas, including the use of biological controls, such as the introduction of parasitic wasps that target the caterpillars. These measures aim to minimize the impact of the caterpillars on forest ecosystems and protect the health of trees.

The Gypsy Moth Caterpillar’s Diet

The Gypsy Moth Caterpillar, scientifically known as Lymantria dispar, is a fascinating creature with a voracious appetite. Its diet primarily consists of the foliage of various tree species, making it a significant concern for forest health.

Preferred Food Sources

When it comes to food, Gypsy Moth Caterpillars have a wide range of preferred sources. They are known to feed on the leaves of oak, maple, birch, and aspen trees, among others. These caterpillars have a remarkable ability to defoliate trees in large numbers, which can have severe consequences for the affected ecosystem.

As they munch on the leaves, Gypsy Moth Caterpillars consume essential nutrients necessary for their growth and development. The abundance of foliage in their diet provides them with the energy they need to transform into adult moths.

Impact on Trees and Foliage

The feeding habits of Gypsy Moth Caterpillars can have devastating consequences for trees and foliage. Large-scale infestations can lead to the complete defoliation of affected trees, leaving them weak and vulnerable to other diseases and pests.

When a tree loses its leaves due to Gypsy Moth Caterpillar infestation, it undergoes significant stress. Without the ability to photosynthesize, the tree’s growth and overall health are compromised. This weakened state makes it more susceptible to secondary infestations and infections from opportunistic pests and pathogens.

Furthermore, the defoliation caused by Gypsy Moth Caterpillars can have cascading effects on the entire ecosystem. Trees play a vital role in providing habitat and food sources for numerous other organisms, including birds, insects, and mammals. When these trees lose their foliage, it disrupts the delicate balance of the ecosystem, impacting the survival and reproduction of other species.