How much does an ER visit cost?

$1,500 – $3,000 average cost without insurance (non-life-threatening condition), $0 – $500 average cost with insurance (after meeting deductible).

Average ER visit cost

An ER visit costs $1,500 to $3,000 on average without insurance, with most people spending about $2,100 for an urgent, non-life-threatening health issue. The cost of an emergency room visit depends on the severity of the condition and the tests, treatments, and medications needed to treat it.

Cost data is from research and project costs reported by BetterCare members.

Emergency room visit cost with insurance

The cost of an ER visit for an insured patient varies according to the insurance plan and the nature and severity of their condition. Some plans cover a percentage of the total cost once you meet your deductible, while others charge an average co-pay of $50 to $500 .

The No Surprises Act , effective January 1, 2022, protects insured individuals from unreasonably high medical bills for emergency services received from out-of-network providers at in-network facilities. The act also established a dispute resolution process for both insured and uninsured or self-pay individuals.

Cost of an ER visit without insurance

An ER visit costs $1,500 to $3,000 on average without insurance for non-life-threatening conditions. Costs can reach $20,000+ for critical conditions requiring extensive testing or emergency surgery. Essentially, the more severe your condition or issue, the more you are likely to pay for the ER visit.

Factors that impact ER visit costs

Many factors affect the cost of an ER visit, including:

Facility type – Freestanding emergency departments often cost 50% more than hospital-based emergency rooms.

Time of day – An ER visit at night typically costs more than the same type of visit during the day.

Level of care – The more severe your condition is, the more time and expertise it takes to diagnose and treat, and the higher the total ER visit cost.

Ambulance ride – An ambulance ride costs $500 to $1,300 on average, depending on whether you need basic or advanced life support during transport.

Medications – Oral medications, injections, or IVs needed during your stay all add the total cost of your ER visit.

Medical equipment & supplies – Any other supplies used to diagnose and treat you—such as a cast for a broken bone or bandages and sutures to close an open wound—increase the cost.

Testing – Each medical test is typically a separate charge. Tests may include urine tests, blood tests, X-rays, or other more advanced imaging tests.

Insurance coverage:

Out-of-pocket costs may be higher for those with high-deductible insurance plans.

While ER visit costs are generally higher for the uninsured, many hospitals offer discounts for self-pay patients.

ER facility fee by level

An ER facility fee ranges from $200 to $4,000 , depending on the severity level of your symptoms and condition. The facility fee is the cost to walk in the door and be evaluated by a physician. Other services you may need, such as lab tests, imaging, and surgical procedures, are charged separately.

To understand your ER bill: Emergency rooms rank severity levels 1 through 5, with Level 1 being the most severe or urgent. However, most of the billing codes for emergency room visits are reversed, with level 1 being the least severe.

Common conditions and procedures

The table below shows the average ER visit cost for common ailments. Prices vary greatly depending on how much testing and expertise is required to accurately diagnose and treat you.

Emergency room vs. urgent care

An ER visit costs $1,500 to $3,000 , while the average urgent care visit costs $150 to $250 without insurance. Urgent care facilities can treat most non-life-threatening conditions and typically have less wait time than the ER. For more detail, check out our guide comparing the cost of an emergency room vs. urgent care .

Other alternatives to the ER for less serious health issues include primary care, telemedicine, and free clinics. Check with the National Association of Free and Charitable Clinics to find a free clinic near you.

FAQs about ER visit costs

Why are er visits so expensive.

ER visits are expensive because emergency rooms run on a 24-hour schedule and require a large and wide range of staff, including front desk personnel, maintenance, nurses, doctors, and surgeons. ERs also run and maintain a lot of expensive equipment and need a constant supply of medications and medical supplies.

While ER visits can be expensive, ER bills are negotiable. If you receive an unexpectedly large ER bill, ask for a discount and question the coding.

Does insurance cover ER visits?

Insurance typically covers some or all of an ER visit, though you may need to meet a deductible first, depending on the plan. The Affordable Care Act requires insurance providers to cover ER visits for "emergency medical conditions" without prior authorization and regardless of whether they are in or out-of-network.

An "emergency medical condition" is considered something so severe that a reasonable person would seek help right away to avoid serious harm.

When should you go to the ER?

You should go to the ER for any serious, potentially life-threatening symptoms, including:

Trouble breathing

Serious head injury

Sudden severe pain

Severe burn

Severe allergic reaction

Major broken bones

Uncontrollable bleeding

Suddenly feeling weak or unable to move, speak, or walk

Sudden change in vision

Sudden confusion

Fever that does not resolve with over-the-counter medicine

Tips to reduce your ER bill

An ER visit can cost thousands of dollars, even if you have insurance. Here are some guidelines to ensure you are not overpaying:

Determine if you truly need an emergency room. If your health issue is not life threatening, consider going to an urgent care facility instead as the cost for the same care can be much less.

Go to a hospital-based ER. Freestanding ER centers typically cost much more than a hospital-based emergency room.

Call ahead to confirm payment options and the current wait time.

Ask about costs up front. If you are uninsured, consider asking the following questions to prevent you from surprises on your future bill:

Do you have discounted pricing for patients without insurance?

Will it cost less if I pay with cash?

What will the fee be for my specific issue?

Do you think I will need additional tests, and what will they cost?

How much do you charge for X-rays?

If I need medication, how much will it cost?

Using our proprietary cost database, in-depth research, and collaboration with industry experts, we deliver accurate, up-to-date pricing and insights you can trust, every time.

How Much Does an ER Visit Cost? Free Local Cost Calculator

It’s true that you can’t plan for a medical emergency, but that doesn’t mean you have to be surprised when it’s time to pay your hospital bill. In 2021, the U.S. government enacted price transparency rules for hospitals in order to demystify health care costs. That means it should be easier to get answers to questions like how much an ER visit costs.

While the question seems pretty straightforward, the answer is more complicated. Your cost will vary based on factors such as if you’re insured, whether you’ve met your deductible, the type of plan you have, and what your plan covers.

There is a lot to consider. This guide will take you through specific scenarios and answer questions about insurance plans, deductibles, co-payments, and discuss scenarios such as how much it costs if you go to the ER when it isn’t an emergency.

You’ll learn a few industry secrets too. Did you know that if you don’t have insurance you might see a higher bill? According to the Wall Street Journal , it’s common for hospitals to charge uninsured and self-pay patients higher rates than insured patients for the same services. So, where can you go if you can’t afford to go to the ER?

Keep reading for all this plus real-life examples and cost-saving tips.

How Much Does an ER Visit Cost Without Insurance?

Everything is more expensive in the ER. According to UnitedHealth, a trip to the emergency department can cost 12 times more than a typical doctor’s office visit. The average ER visit is $2,200, and doesn’t include procedures or medications.

If you want to get a better idea of what an ER visit will cost in your area, check out our medical price comparison tool that analyzes data from thousands of hospitals.

Compare Procedure Costs Near You

Other out-of-pocket expenses you may incur include bills from third parties. A growing number of emergency departments in the United States have become business entities separate from the hospital. So, third-party providers may bill you too, like:

- EMS services, like an ambulance or helicopter

- ER physicians

- Attending physician

- Consulting physicians

- Advanced practice nurses (CRNA, NP)

- Physician assistants (PA)

- Physical therapists (PT)

And if your insurance company fails to pay, you may have to pay these expenses out-of-pocket.

How Much Does an ER Visit Cost With Insurance?

The easiest way to estimate out-of-pocket expenses for an ER visit (or any other health care service) is to read your insurance policy. You’ll want to look for information around these terms:

- Deductible: The amount you have to pay out-of-pocket before your insurance kicks in .

- Copay: A set fee you pay upfront before a covered medical service or procedure.

- Coinsurance: The percentage you pay for a service or a procedure once you’ve met the deductible.

- Out-of-pocket maximum: The most you will pay for covered services in a rolling year. Once met, your insurance company will pay 100% of covered expenses for the rest of the year.

Closely related to out-of-pocket expenses like deductibles and co-insurance are premiums. A premium is the monthly fee you (or your sponsor) pay to the insurance company for coverage. If you pay a higher premium, you’ll have a lower deductible and fewer out-of-pocket costs whenever you use your insurance to pay for services such as a visit to the ER. The opposite is also true — high deductible health plans (HDHP) offer lower monthly payments but much higher deductibles.

Sample ER Visit Cost

Using a few examples from plans available on the Marketplace on Healthcare.gov (current as of November 2021), here’s how this might play out in real life:

Rob is a young, healthy, single guy. He knows he needs health insurance but he feels reasonably sure that the only time he’d ever use it is in case of an emergency. Here’s the plan he chooses:

Plan: Blue Cross/Blue Shield Bronze Monthly premium: $394 Deductible: $7,000 Out-of-pocket maximum: $7,000 ER coverage: 100% after meeting the deductible

Rob does the math and considers the worst case scenario. If he does go to the ER, he’ll pay full price if he hasn’t yet met his deductible. But since both his deductible and his maximum out-of-pocket are the same, $7,000 is the most he’ll have to pay before his insurance kicks in at 100%.

Now imagine that Rob gets married and is about to start a family. He might need a different insurance plan to account for more hospital bills, doctors appointments, and inevitable emergency room visits.

Since Rob knows he’ll be using his insurance more often, he picks a plan with a lower deductible that covers more things.

Plan: Bright HealthCare Gold Monthly premium: $643 Deductible: $0 Out-of-pocket maximum: $6,500 ER coverage: $500 Vision: $0 Generic prescription: $0 Primary care: $0 Specialist: $40

This time Rob goes with a zero deductible plan with a higher monthly premium. It’s more out-of-pocket each month, but since his plan covers doctor’s visits, prescription drugs, and vision, he feels more prepared as his lifestyle shifts into family mode.

If he has to go to the ER for any reason, all he’ll pay is $500 and his insurance pays the rest. And worse case scenario, the most he’ll pay out-of-pocket in a year is $6,500.

How Much Does an ER Visit Cost if You Have Medicare?

Medicare Part A only covers an emergency room visit if you’re admitted to the hospital. Medicare Part B covers 100% of most ER costs for most injuries, or if you become suddenly ill. Unlike private insurance and insurance purchased on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplace, Medicare rarely covers ER visits that happen while you’re outside of the United States.

To learn more, read: How to Use the Healthcare Marketplace to Buy Insurance

How Much Does an ER Visit Cost for Non-Emergencies?

When you have a sick child but lack insurance, haven’t met your deductible, or if you’re between paychecks, just knowing you can go to the ER without being hassled for money feels like such a relief. ER staff won’t demand payment upfront, and they usually don’t ask about insurance or assess your ability to pay until after discharge.

There are other reasons, too. You might be tempted to go to the ER for situations that are less than emergent because emergency departments provide easy access to health services 24/7, including holidays and the odd hours when your primary care physician isn’t available. If you’re one of the 61 million Americans who are uninsured or underinsured , you might go to the ER because you don’t know where else to go.

What you may not understand is the cost of an ER visit without insurance can total thousands of dollars. Consumers with ER bills that get sent to collections face some of the most aggressive debt collection practices of any industry. Collection accounts and charge-offs could affect your credit score for the better part of a decade.

Did you know that charges begin racking up as soon as you give the clerk your name and Social Security number? There are tons of horror stories out there about people receiving medical bills after waiting, some for many hours, and leaving without treatment.

4 ER Alternatives Ranked by Level of Care

First and foremost, if you’re experiencing a medical emergency, call 911 or go to the closest emergency room. Do not rely on this or any other website for advice or communication.

If you’re not sure whether your condition warrants immediate, high-level emergency care, you can always call your local ER and ask to speak to their triage nurse. They can quickly assess how urgent the situation is.

If you are looking for a lower-cost alternative to the ER, this list provides a few options. Each option is ranked by their ability to provide you with a certain level of care from emergent care to the lowest level, which is similar to the routine care you would receive at a doctor’s office.

1. Charitable Hospitals

There are around 1,400 charity hospitals , clinics, and pharmacies dedicated to serving low-income families, including the uninsured. Most charitable, not-for-profit medical centers provide emergency room services, making it a good option if you’re uninsured and worried about accruing substantial medical debt.

ERs at charitable hospitals provide the same type of medical care for conditions like trauma, broken bones, and life-threatening issues like chest pain and difficulty breathing. The major difference is the price tag. Emergency room fees at a charity hospital are usually flexible and almost always based on your income.

2. Urgent Care Centers

Urgent care centers are free-standing facilities designed to treat patients with serious but not life-threatening conditions. Also called “doc in a box,” these ambulatory care centers are a good choice for treating stable but chronic health issues, fever, urinary tract infections, back pain, abdominal pain, and moderately high blood pressure, to name a few.

Urgent care clinics usually have a medical doctor on-site. Some clinics offer point-of-care diagnostic tests like ultrasound and X-rays, as well as basic lab work. The average cost for an urgent care visit is around $180, according to UnitedHealth.

3. Retail Health Clinics

You may have noticed small retail health clinics (RHC) popping up in national drugstore chains like CVS, Walgreens, and in big-box stores like Target and Walmart. The Little Clinic is an example of an RHC that offers walk-in health care services at 190 supermarkets across the United States.

RHCs help low-acuity patients with minor medical problems like sore throat, cough, flu-like symptoms, and other conditions normally treated in a doctor’s office. If you think you’ll need lab tests or other procedures, an RHC may not be the best choice. Data from UnitedHealth puts the average cost for an RHC visit at $100.

4. Telehealth Visits

Telehealth, in some form, has been around for decades. Until recently, it was mostly used to provide access to care for patients living in the most remote or rural areas. Since 2020, telehealth visits over the phone, via chat, or through videoconferencing have become a legitimate and extremely cost-effective alternative to in-person office visits.

Telehealth is perfect for some types of mental health therapies, follow-up appointments, and triage. For self-pay, a telehealth visit only costs around $50, according to UnitedHealth.

Tips for Taking Control of Your Health Care

- Don’t procrastinate. Delaying the care you need for too long will end up costing you more in the end.

- Switch your focus from reactive care to proactive care. Figuring out how to pay for an ER visit is a lot harder (and costlier) than preventing an ER visit in the first place. Data show that preventive health care measures lead to fewer illnesses and better outcomes.

- Plan for the unknown. It’s inevitable that at some point in your life you’ll need health care. Start a savings account fund or better yet, enroll in a health savings account (HSA). If you’re employed (even part-time) you already qualify for an HSA. A contribution of just $9 a paycheck could add up to $468 tax-free dollars for you to spend on health care every year. Unlike the use-it-or-lose-it savings plans of the past, modern plans don’t expire. You can use HSA dollars to pay for out-of-pocket costs like copayments, deductibles, and for services that your health insurance may not cover, like dental and vision services.

- Advocate for yourself. There is nothing more empowering than taking charge of your health. Shop around for services and compare prices on procedures to make sure you’re getting the best prices possible.

- If you are uninsured or doing self-pay, negotiate your bill and ask for a cash discount.

Estimate the Cost of the ER Before You Need It

It’s stressful to think about money when you’re facing an emergency. Research the costs of your nearest ER before you actually need to go with Compare.com’s procedure cost comparison tool .

All you have to do is enter your ZIP code and you’ll immediately see out-of-pocket costs for ER visits at your local emergency rooms. It works for other medical services too, like MRIs, routine screenings, outpatient procedures, and more. Find the treatment you need at a price you can afford.

Disclaimer: Compare.com does not offer medical advice and is in no way a substitute for any medical advice received from health professionals. Compare.com is unable to offer any advice on any medical procedure you may need.

Nick Versaw leads Compare.com's editorial department, where he and his team specialize in crafting helpful, easy-to-understand content about car insurance and other related topics. With nearly a decade of experience writing and editing insurance and personal finance articles, his work has helped readers discover substantial savings on necessary expenses, including insurance, transportation, health care, and more.

As an award-winning writer, Nick has seen his work published in countless renowned publications, such as the Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, and U.S. News & World Report. He graduated with Latin honors from Virginia Commonwealth University, where he earned his Bachelor's Degree in Digital Journalism.

Compare Car Insurance Quotes

Get free car insurance quotes, recent articles.

- An emergency room visit typically is covered by health insurance. For patients covered by health insurance, out-of-pocket cost for an emergency room visit typically consists of a copay, usually $50-$150 or more, which often is waived if the patient is admitted to the hospital. Depending on the plan, costs might include coinsurance of 10% to 50%.

- For patients without health insurance, an emergency room visit typically costs from $150-$3,000 or more, depending on the severity of the condition and what diagnostic tests and treatment are performed. In some cases, especially where critical care is required and/or a procedure or surgery is performed, the cost could reach $20,000 or more. For example, at Park Nicollet Methodist Hospital in Minnesota, a low-level emergency room visit, such as for a minor laceration, a skin rash or a minor viral infection, costs about $150 ; a moderate-level visit, such as for a urinary tract infection with fever or a head injury without neurological symptoms, about $400 ; and a high-level visit, such as for chest pains that require multiple diagnostic tests or treatments, or severe burns or ingestion of a toxic substance, about $1,000, not including the doctor fees. At Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center[ 1 ] , a low-level emergency room visit costs about $220, including hospital charge and doctor fee, with the uninsured discount, while a moderate-level visit costs about $610 and a high-level visit about $1,400 .

- Services, diagnostic tests and laboratory fees add to the final bill. For example, Wooster Community Hospital, in Ohio, charges about $170 for a simple suture, $200 for a complex suture, about $170 for a minor procedure and about $400 for a major procedure, not including doctor fees, medicine or supplies.

- A doctor fee could add hundreds or thousands of dollars to the final cost. For example, at Grand Lake Health System[ 2 ] in Ohio, an emergency room doctor charges about $100 for basic care, such as a wound recheck or simple laceration repair; about $300 for mid-level care, such as treatment of a simple fracture; about $870 for advanced-level care, such as frequent monitoring of vital signs and ordering multiple diagnostic tests, administering sedation or a blood transfusion for a seriously injured or ill patient; and about $1,450 for critical care, such as major trauma care or major burn care that could include chest tube insertion and management of IV medications and ventilator for a patient with a complex, life-threatening condition. At the Kettering Health Network, in Ohio, a low-level visit costs about $350, a high-level visit costs about $2,000 and critical care costs almost $1,700 for the first hour and $460 for each additional half hour; ER procedures or surgeries cost $460-$2,300 .

- According to the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality[ 3 ] the average emergency room expense in 2008 was $1,265 .

- According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in 2008, about 18%of emergency room patients waited less than 15 minutes to see a doctor, about 37%waited 15 minutes to an hour, about 15% waited one to two hours, about 5% waited two to three hours, about 2% waited three to four hours, and about 1.5% waited four to six hours.

- In some cases, the doctor might recommend the patient be admitted to the hospital. The American College of Emergency Physicians Foundation offers a guide[ 4 ] on what to expect.

- An ambulance ride typically costs $400-$1,200 or more, depending on the location and services performed.

- An urgent care center offers substantial savings for more minor ailments. DukeHealth.org offers a guide[ 5 ] on when to seek urgent care. An urgent care visit typically costs between 20% and 50% of the cost of an emergency room visit. MainStreetMedica.com offers a cost-comparison tool for common ailments.

- Hospitals often offer discounts of up to 50% or more for self-pay/uninsured emergency room patients. For example, Ventura County Medical Center[ 6 ] in California offers ER visits, including the doctor fee and emergency room fee but not including lab tests, X-rays or procedures, for $150 for patients up to 200% of the federal poverty level, for $225 for patients between 200% and 500% of the federal poverty level and $350 for patients from 500% to 700% of the federal poverty level.

- The American College of Emergency Physicians Foundation offers a primer[ 7 ] on when to go to the emergency room.

- In most cases, it is recommended to go to the nearest emergency room. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services offers a hospital-comparison tool[ 8 ] that lists hospitals near a chosen zip code.

- patients.dartmouth-hitchcock.org/billing_questions/out_of_pocket_estimator_dhmc.ht...

- www.grandlakehealth.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=106&Itemid=60

- meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_stats/tables_compendia_hh_interactive.jsp?_SERVICE=MEPS...

- www.EmergencyCareforYou.org/VitalCareMagazine/ER101/Default.aspx?id=1288

- www.dukehealth.org/health_library/health_articles/wheretogo

- resources.vchca.org/documents/SELF%20PAY%20DISCOUNT%20GRID%20-%20BOARD%20LETTER%20...

- www.EmergencyCareforYou.org/YourHealth/AboutEmergencies/Default.aspx?id=26018

- www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/(S(efntd2saaeir2l5pgarwuvvg))/search.aspx?AspxAut...

- For Medicare

- For Providers

- For Brokers

- For Employers

- For Individuals & Families:

Shop for Plans

Shop for your own coverage.

- Other Supplemental

Plans through your employer

- Learn about the medical, dental, pharmacy, behavioral, and voluntary benefits your employer may offer.

- Explore coverage through work

- How to Buy Health Insurance

- Types of Dental Insurance

- Open Enrollment vs. Special Enrollment

- See all topics

Looking for Medicare coverage?

- Shop for Medicare plans

- Member Guide

- Find a Doctor

- Log in to myCigna

Emergency Room Visit: When to Go, What to Expect, Wait Times, and Cost

Knowing when and why to go for an emergency room visit can help you plan for care in the event of a medical emergency.

How much does it cost to go to an emergency room?

Emergency Room (ER) costs can vary greatly depending on what type of medical care you need. How much you pay for the visit depends on your health insurance plan. Most health plans may require you to pay something out-of-pocket for an emergency room visit. A visit to the ER may cost more if you have a High-Deductible Health Plan (HDHP) and you have not met your plan’s annual deductible. HDHP's typically offer lower monthly premiums and higher deductibles than traditional health plans. Your plan will start paying for eligible medical expenses once you’ve met the plan’s annual deductible. Here are some tips to pay less out of pocket .

When should I go to an emergency room?

Emergency rooms are often very busy because many people don’t know what type of care they need, so they immediately go to the ER when they are sick or hurt. You should make an emergency room visit for any condition that’s considered life-threatening.

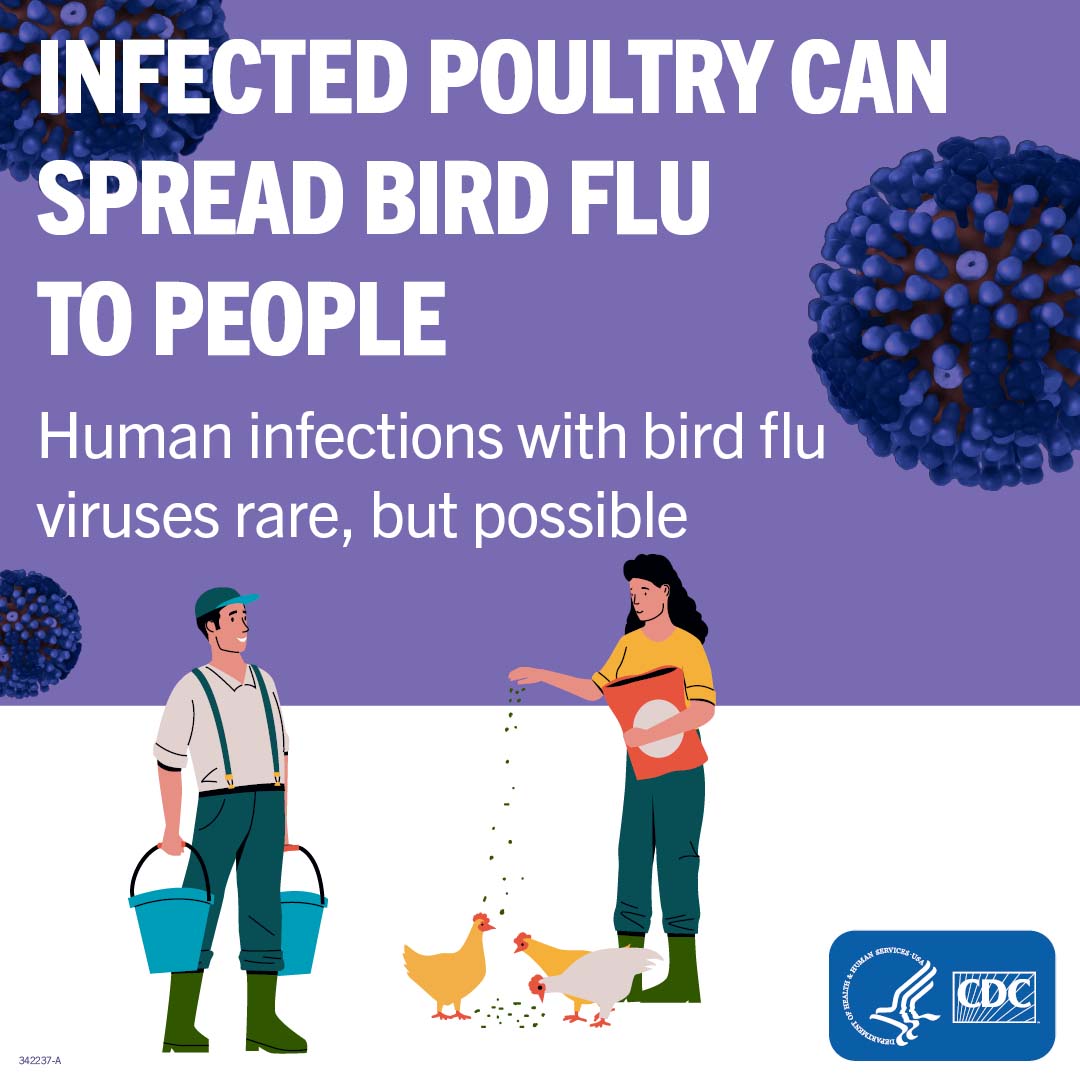

Life-threatening conditions include, but are not limited to, things like a serious allergic reaction, trouble breathing or speaking, disorientation, a loss of consciousness, or any physical trauma.

If you need to be treated for problems that are considered non-life threatening, such as an earache, fever and flu symptoms, minor animal bites, mild asthma, or a mild urinary tract infection, consider seeing your doctor or visiting an urgent care center or convenience care clinic.

What is the cost of an emergency room visit without insurance?

Emergency room costs with or without health insurance can be very high. If you have health insurance, review your plan documents for details on the costs associated with your plan, including your plan deductible, coinsurance, and copay requirements.

If you don’t have insurance, you may be required to pay the full cost of your treatment, which can vary by facility and the type of treatment required. Always plan ahead for sudden sickness, injury, or other medical needs, so you know where to go and how much it could cost. If you need medical care, but it’s not life-threatening you may not have to go to the ER—there are other more affordable options:

- Urgent care center: Staffed by doctors, nurses, and other medical staff who can treat things like earaches, urinary tract infections, minor cuts, nausea, vomiting, etc. Wait times may be shorter and using an urgent care center could save you hundreds of dollars when compared to an ER.

- Convenience care clinic: Walk-in clinics are typically located in a pharmacy (CVS, Walgreens, etc.) or supermarket/retail store (Target, Walmart, etc.). These clinics are staffed with physician assistants and nurse practitioners who can provide care for minor cold, fever, flu, rashes and bruises, head lice, allergies, sinus/ear infections, urinary tract infections, even flu and shingles shots. No appointments are needed, wait times are usually minimal, and a convenience care clinic costs much less than an ER.

Plan ahead for when you need medical care. You may not need an emergency room visit and the bill that could come with it.

What are common emergency room wait times?

Emergency room wait times vary according to hospital and location. Patients in the ER are seen based on how serious their condition is. This means that the patients with life-threatening conditions are treated first, and those with non-life threatening conditions have to wait.

To help reduce ER wait times, health care facilities encourage you to plan ahead for care, so when you’re sick or hurt, you know if the ER is right for your medical condition.

An emergency room visit can take up time and money if your problem is not life-threatening. Consider other care options, such as an urgent care center, convenience care clinic, your doctor, or a virtual doctor visit (video chat/telehealth)—all of which could be faster and save you money out of your own pocket if the medical problem is non-life threatening.

If you have health insurance, be sure to check your plan documents to see what types of care options are eligible for coverage under your plan, including whether or not you need to stay in your plan’s network.

Is taking an ambulance to the emergency room free?

An ambulance ride is not free, but your insurance may cover some of the costs for the ride, as well as the emergency room visit. Check your plan benefits to see what out-of-pocket expenses you are responsible for when it comes to an ambulance ride and a visit to the ER.

Plan ahead for times you may need immediate medical care. Review the details of your health plan so you know the costs for an ER visit should you ever need it. Know when it’s best to go to the emergency room and when going somewhere else, like an urgent care center, convenience care clinic, your doctor, or even a virtual doctor visit (video chat/telehealth), is the right option that may save you time and money.

- Emergency Care

- What is Inpatient vs. Outpatient Care?

- Urgent Care vs. Emergency Room

- Shop Around for MRIs, CTs, and PET Scans

Explore Our Plans and Policies

- Health Insurance

- Dental Insurance

- Supplemental Insurance

Back to Knowledge Center

The information provided here is for educational purposes only. It does not constitute medical advice and is not a substitute for proper medical care provided by a physician. Cigna Healthcare SM assumes no responsibility for any circumstances arising out of the use, misuse, interpretation or application of this information. Always consult your doctor for appropriate examinations, treatment, testing, and care recommendations. In an emergency, dial 911 or visit the nearest emergency room.

I want to...

- Get an ID card

- File a claim

- View my claims and EOBs

- Check coverage under my plan

- See prescription drug list

- Find an in-network doctor, dentist, or facility

- Find a form

- Find 1095-B tax form information

- View the Cigna Healthcare Glossary

- Contact Cigna Healthcare

- Individuals and Families

Secure Member Sites

- myCigna member portal

- Health Care Provider portal

- Cigna for Employers

- Client Resource Portal

- Cigna for Brokers

The Cigna Group Information

- About Cigna Healthcare

- The Cigna Group

- Third Party Administrators

- International

- Evernorth Health Services

- Terms of Use

- Product Disclosures

- Company Names

- Customer Rights

- Accessibility

- Non-Discrimination Notice

- Language Assistance [PDF]

- Report Fraud

- Washington Consumer Health Data Privacy Notice

- Cookie Preferences

Individual and family medical and dental insurance plans are insured by Cigna Health and Life Insurance Company (CHLIC), Cigna HealthCare of Arizona, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of Illinois, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of Georgia, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of North Carolina, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of South Carolina, Inc., and Cigna HealthCare of Texas, Inc. Group health insurance and health benefit plans are insured or administered by CHLIC, Connecticut General Life Insurance Company (CGLIC), or their affiliates (see a listing of the legal entities that insure or administer group HMO, dental HMO, and other products or services in your state). Accidental Injury, Critical Illness, and Hospital Care plans or insurance policies are distributed exclusively by or through operating subsidiaries of The Cigna Group Corporation, are administered by Cigna Health and Life Insurance Company, and are insured by either (i) Cigna Health and Life Insurance Company (Bloomfield, CT). The Cigna Healthcare name, logo, and other Cigna Healthcare marks are owned by The Cigna Group Intellectual Property, Inc.

All insurance policies and group benefit plans contain exclusions and limitations. For availability, costs and complete details of coverage, contact a licensed agent or Cigna Healthcare sales representative. This website is not intended for residents of Arizona and New Mexico.

Selecting these links will take you away from Cigna.com to another website, which may be a non-Cigna Healthcare website. Cigna Healthcare may not control the content or links of non-Cigna Healthcare websites. Details

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Health Care

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

Why An ER Visit Can Cost So Much — Even For Those With Health Insurance

Terry Gross

Vox reporter Sarah Kliff spent over a year reading thousands of ER bills and investigating the reasons behind the costs, including hidden fees, overpriced supplies and out-of-network doctors.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2006 Feb-.

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs [Internet].

Statistical brief #268 costs of emergency department visits in the united states, 2017.

Brian J. Moore , Ph.D. and Lan Liang , Ph.D.

Published: December 8, 2020 .

- Introduction

Emergency department (ED) visits have grown in the United States, with the rate of increase from 1996 to 2013 exceeding that for hospital inpatient care. 1 In 2017, 13.3 percent of the U.S. population incurred at least one expense for an ED visit. 2 Furthermore, more than 50 percent of hospital inpatient stays in 2017 included evidence of ED services prior to admission. 3 Trends in ED volume vary significantly by patient and hospital characteristics, but an examination of nationwide costs by these characteristics has not yet been explored in the literature. 4

This Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Brief presents statistics on the cost of ED visits in the United States using the 2017 Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS). Total ED charges were converted to costs using HCUP Cost-to-Charge Ratios based on hospital accounting reports from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). ED visits include patients treated and released from the ED, as well as those admitted to the same hospital through the ED. Aggregate costs, average costs, and number of ED visits are presented by patient and hospital characteristics. Because of the large sample size of the NEDS data, small differences can be statistically significant. Thus, only percentage differences greater than or equal to 10 percent are discussed in the text.

- There were 144.8 million total emergency department (ED) visits in 2017 with aggregate ED costs totaling $76.3 billion (B).

- Aggregate ED costs were higher for females ($42.6B, 56 percent) than males ($33.7B, 44 percent); 55 percent of total ED visits were for females.

- Average cost per ED visit increased with age, from $290 for patients aged 17 years and younger to $690 for patients aged 65 years and older.

- As community-level income increased, shares of aggregate ED costs decreased and average cost per visit increased.

- In rural areas, one half of ED visit costs were for patients from the lowest income communities.

- The expected payer with the largest share of aggregate costs was private insurance in large metropolitan areas (31.4 percent of $39.5B) and Medicare in micropolitan (34.0 percent of $7.6B) and rural (37.3 percent of $5.5B) areas.

- Patients aged 18–44 years represented the largest share of aggregate ED costs in large metropolitan, small metropolitan, and micropolitan areas (36.4, 34.2, 32.5 percent, respectively). Patients aged 65 years and older represented the largest share of aggregate ED costs in rural areas (32.5 percent).

Aggregate costs for emergency department (ED) visits by patient sex and age group, 2017

Figure 1 presents aggregate ED visit costs by patient sex and age group in 2017 as well as number of ED visits. Estimates of aggregate cost use the product of the number of cases and the average estimated cost per visit to account for records with missing ED charge information. Aggregate cost decompositions among different descriptive statistics or using multiple levels of aggregation in a single computation could lead to slightly different total cost estimates due to the use of slightly different and more specific estimates of the missing information.

Aggregate ED visit costs by patient sex and age, 2017. Abbreviation: ED, emergency department Notes: Statistics for ED visits with missing or invalid patient characteristics are not presented. Patient age and sex were each missing for <0.1% of (more...)

- Aggregate ED visit costs in 2017 were higher overall for females than for males. Of the $76.3 billion in aggregate ED visit costs in 2017, females accounted for $42.6 billion (55.9 percent) and males accounted for $33.7 billion (44.1 percent). This cost differential was largely driven by a difference in ED visit volume, with females having a larger number of ED visits than males (80.2 vs. 64.6 million visits, or 55.4 vs. 44.6 percent of visits). Females had higher aggregate ED visit costs and more ED visits for all age groups except children. The discrepancy was highest for patients aged 18–44 years, with aggregate ED visit costs for females approximately 50 percent higher than costs for males ($15.9 vs. $10.7 billion), followed by patients aged 65 years and older, for which aggregate ED visit costs were approximately one-third higher for females than for males ($11.5 vs. $8.6 billion).

Costs of ED visits by patient characteristics, 2017

Table 1 presents the aggregate and average costs for ED visits, the number of ED visits, and the distributions of costs and visits, by select patient characteristics in 2017.

Aggregate costs, average costs, and number of ED visits by patient characteristics, 2017.

- In 2017, aggregate ED visit costs totaled $76.3 billion across 144.8 million ED visits, with an average cost per visit of $530. Aggregate ED visit costs totaled $76.3 billion in the United States in 2017, encompassing 144.8 million ED visits with an average cost per visit of $530. Routine discharge was the most frequent disposition from the ED, representing 80.8 percent of aggregate ED costs and a similar share of ED visits. Transfers represented 6.2 percent of aggregate ED costs but just 3.0 percent of ED visit volume because they had the highest average cost of any discharge disposition at $1,100 per ED visit. In contrast, ED visits resulting in an inpatient admission to the same hospital had the lowest average cost of any discharge disposition at $360 per ED visit and represented 9.4 percent of aggregate ED costs and 14.0 percent of ED visits.

- The share of aggregate ED visit costs attributed to patients aged 65 years and older was higher than the share of ED visits for this group, and the average cost per visit was highest among patients aged 65 years and older. Aggregate ED visit costs among patients aged 65 years and older totaled $20.2 billion (26.4 percent of the $76.3 billion total for the entire United States in 2017) despite just 29.2 million ED visits from patients in this age group (20.2 percent of the 144.8 million total). Conversely, the share of aggregate ED costs attributed to patients aged 17 years and younger was substantially lower than this group’s corresponding share of ED visits (10.3 percent of ED costs vs.18.5 percent of ED visits). This differential is due in part to the difference in average cost per visit, which increased with age. The average cost per visit among patients aged 65 years and older was more than twice as high as average costs among patients aged 17 years and younger ($690 vs. $290 per visit).

- Medicaid as the primary expected payer had the lowest average cost per ED visit, more than 50 percent lower than average costs for Medicare and one-third lower than for private insurance. Medicaid as the primary expected payer had an average cost per ED visit that was more than 50 percent lower than average costs per visit for Medicare ($420 vs. $660 per visit) and one-third lower than average costs for private insurance ($420 vs. $560 per visit). Due in part to these differences in average costs by expected payer, Medicare represented 30.1 percent of aggregate ED visit costs but 24.1 percent of total ED visits. In contrast, Medicaid represented 25.0 percent of ED costs but 31.5 percent of ED visits.

- As community-level income increased, the share of aggregate ED visit costs decreased and average cost per ED visit increased. The share of ED visit costs and ED visits decreased as community-level income increased. Patients residing in communities with the lowest income (quartile 1) represented roughly one-third of aggregate ED visit costs and ED visits (31.4 and 34.3 percent, respectively). Patients residing in quartiles 2 and 3 represented approximately one-fourth and one-fifth of aggregate ED visit costs and ED visits, respectively. Patients residing in communities with the highest income (quartile 4) represented less than one-fifth of aggregate ED costs and ED visits (18.1 and 16.0 percent, respectively). In contrast, average cost per ED visit increased as community-level income increased, ranging from $480 in communities with the lowest income (quartile 1) to $600 in communities with the highest income (quartile 4).

- The share of aggregate ED visit costs was highest among patients residing in large metropolitan areas. Aggregate ED visit costs for large metropolitan areas totaled $39.5 billion in 2017, more than half of the $76.3 billion in ED costs for the entire United States. The share of aggregate ED costs in large metropolitan areas was analogous to the overall distribution of ED visits in these areas: 51.8 percent of aggregate ED costs and 50.4 percent of ED visits.

Distribution of aggregate ED visit costs for location of patient residence by patient characteristics, 2017

Figures 2 – 4 present the distribution of aggregate costs for ED visits based on the location of the patient’s residence by age ( Figure 2 ), community-level income ( Figure 3 ), and primary expected payer ( Figure 4 ).

Aggregate ED visit costs by age and patient location, 2017. Abbreviations: B, billion; ED, emergency department; M, million Notes: Statistics for ED visits with missing or invalid patient characteristics are not presented. Patient age and patient location (more...)

Aggregate ED visit costs by primary expected payer and patient location, 2017. Abbreviations: B, billion; ED, emergency department; M, million Notes: Statistics for ED visits with missing or invalid patient characteristics are not presented. Expected (more...)

Aggregate ED visit costs by community-level income and location of patient’s residence, 2017. Abbreviations: B, billion; ED, emergency department; M, million Notes: Statistics for ED visits with missing or invalid patient characteristics are not (more...)

Figure 2 presents the distribution of aggregate costs for ED visits by patient age based on the location of the patient’s residence in 2017.

- Patients aged 18–44 years represented the largest share of aggregate ED visit costs in all locations except rural areas where patients aged 65 years and older represented the largest share. Compared with other age groups, patients aged 18–44 years represented the largest share of aggregate ED visit costs in large metropolitan areas in 2017 (36.4 percent). The share of ED costs attributed to patients aged 18–44 years also was larger than for other age groups in small metropolitan and micropolitan areas (34.2 and 32.5 percent, respectively). Overall, the share of ED costs attributed to patients aged 18–44 years decreased as urbanization decreased, from 36.4 percent in large metropolitan areas to 29.8 percent in rural areas. In rural areas, patients aged 65 years and older accounted for the largest share of aggregate ED visit costs (32.5 percent) compared with other age groups. The share of ED costs attributed to patients aged 65 years and older increased as urbanization decreased, from 24.7 percent in large metropolitan areas to 32.5 percent in rural areas. The share of aggregate ED visit costs attributed to patients aged 45–64 years and those aged 17 years and younger were similar across all patient locations (approximately 28 and 10 percent, respectively).

Figure 3 presents the distribution of aggregate costs for ED visits by quartile of community-level household income in the patient’s ZIP Code based on the location of the patient’s residence in 2017.

- In large metropolitan areas, patients residing in communities with the highest and lowest incomes represented the largest shares of aggregate ED visit costs. For other locations, patients in communities with lower incomes represented the largest share of ED costs. Patients residing in communities with the highest and lowest incomes (quartiles 4 and 1) accounted for 28.1 and 26.6 percent, respectively, of the $39.5 billion in aggregate ED visit costs in large metropolitan areas in 2017. In contrast, patients residing in communities with the two lowest income quartiles represented the largest share of ED costs for other patient locations (small metropolitan, micropolitan, and rural).

- As urbanization decreased, the share of aggregate ED visit costs for patients in the lowest income quartile increased and the share for those in the highest income quartile decreased. The share of aggregate ED visit costs attributed to patients residing in communities in the lowest income quartile (quartile 1) increased as urbanization decreased, from 26.6 percent in large metropolitan areas to 48.8 percent in rural areas. In contrast, the share of ED visit costs attributed to patients residing in communities in the highest income quartile (quartile 4) decreased as urbanization decreased, from 28.1 percent in large metropolitan areas to 1.2 percent in rural areas.

Figure 4 presents the distribution of aggregate costs for ED visits by primary expected payer based on the location of the patient’s residence in 2017.

- Private insurance as the primary expected payer accounted for the largest share of aggregate ED visit costs among patients living in large metropolitan areas. Medicare represented the largest share of ED costs in micropolitan and rural areas. Compared with other primary expected payers, private insurance represented the largest share of aggregate ED visit costs among those living in large metropolitan areas in 2017 (31.4 percent). The share of ED costs attributed to private insurance decreased as urbanization decreased, from 31.4 percent in large metropolitan areas to 27.9 percent in rural areas. More than one-third of ED visit costs were attributed to Medicare as the primary expected payer in micropolitan and rural areas. The share of ED costs attributed to Medicare increased as urbanization decreased, from 28.0 percent in large metropolitan areas to 37.3 percent in rural areas.

Costs of ED visits by hospital characteristics, 2017

Table 2 presents the aggregate and average costs for ED visits, the number of ED visits, and the distributions of costs and visits, by select hospital characteristics in 2017.

Aggregate costs, average costs, and number of ED visits by hospital characteristics, 2017.

- Aggregate ED visit costs were highest for hospitals located in the South in 2017. Aggregate ED visit costs in the South were $27.5 billion in 2017 (36.1 percent of the total $76.3 billion for the United States). The share of ED visit volume for the South was even larger (40.0 percent of the 144.8 million total visits). The distribution of aggregate ED visit costs across other hospital characteristics largely followed the pattern of the number of ED visits. Aggregate ED costs were highest in private, nonprofit hospitals; teaching hospitals; and hospitals not designated as a trauma center (72.0, 64.1, and 52.5 percent of ED costs, respectively). ED visits at private, for-profit hospitals had lower average costs per visit than did visits at either private, nonprofit or public hospitals ($420 vs. $540 and $550 per visit).

- About Statistical Briefs

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs provide basic descriptive statistics on a variety of topics using HCUP administrative healthcare data. Topics include hospital inpatient, ambulatory surgery, and emergency department use and costs, quality of care, access to care, medical conditions, procedures, and patient populations, among other topics. The reports are intended to generate hypotheses that can be further explored in other research; the reports are not designed to answer in-depth research questions using multivariate methods.

- Data Source

The estimates in this Statistical Brief are based upon data from the HCUP 2017 Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS).

- Definitions

Types of hospitals included in the HCUP Nationwide Emergency Department Sample

The Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS) is based on emergency department (ED) data from community acute care hospitals, which are defined as short-term, non-Federal, general, and other specialty hospitals available to the public. Included among community hospitals are pediatric institutions and hospitals that are part of academic medical centers. Excluded are long-term care facilities such as rehabilitation, psychiatric, and alcoholism and chemical dependency hospitals. Hospitals included in the NEDS have EDs, and no more than 90 percent of their ED visits result in admission.

Unit of analysis

The unit of analysis is the ED visit, not a person or patient. This means that a person who is seen in the ED multiple times in 1 year will be counted each time as a separate visit in the ED.

Costs and charges

Total ED charges were converted to costs using HCUP Cost-to-Charge Ratios based on hospital accounting reports from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). a Costs reflect the actual expenses incurred in the production of hospital services, such as wages, supplies, and utility costs; charges represent the amount a hospital billed for the case. For each hospital, a cost-to-charge ratio constructed specifically for the hospital ED is used. Hospital charges reflect the amount the hospital billed for the entire ED visit and do not include professional (physician) fees.

Total charges were not available on all NEDS records. About 13 percent of all ED visits (weighted) in the 2017 NEDS were missing information about ED charges, and therefore, ED cost could not be estimated. For ED visits that resulted in admission, 24 percent of records were missing ED charges. For ED visits that did not result in admission, 11 percent of records were missing ED charges. The missing information was concentrated in the West (59 percent of records missing ED charges). For this Statistical Brief, the methodology used for aggregate cost estimation was analogous to what is recommended for the estimation of aggregate charges in the Introduction to the HCUP NEDS documentation. b Aggregate costs were estimated as the product of number of visits and average cost per visit in each reporting category. If a stay was missing total charges, average cost was imputed using the average cost for other stays with the same combination of payer characteristics. Therefore, a comparison of aggregate cost estimates across different tables, figures, or characteristics may result in slight discrepancies.

How HCUP estimates of costs differ from National Health Expenditure Accounts

There are a number of differences between the costs cited in this Statistical Brief and spending as measured in the National Health Expenditure Accounts (NHEA), which are produced annually by CMS. c The largest source of difference comes from the HCUP coverage of ED treatment only in contrast to the NHEA inclusion of inpatient and other outpatient costs associated with other hospital-based outpatient clinics and departments as well. The outpatient portion of hospitals’ activities has been growing steadily and may exceed half of all hospital revenue in recent years. On the basis of the American Hospital Association Annual Survey, 2017 outpatient gross revenues (or charges) were about 49 percent of total hospital gross revenues. d

Smaller sources of differences come from the inclusion in the NHEA of hospitals that are excluded from HCUP. These include Federal hospitals (Department of Defense, Veterans Administration, Indian Health Services, and Department of Justice [prison] hospitals) as well as psychiatric, substance abuse, and long-term care hospitals. A third source of difference lies in the HCUP reliance on billed charges from hospitals to payers, adjusted to provide estimates of costs using hospital-wide cost-to-charge ratios, in contrast to the NHEA measurement of spending or revenue. HCUP costs estimate the amount of money required to produce hospital services, including expenses for wages, salaries, and benefits paid to staff as well as utilities, maintenance, and other similar expenses required to run a hospital. NHEA spending or revenue measures the amount of income received by the hospital for treatment and other services provided, including payments by insurers, patients, or government programs. The difference between revenues and costs includes profit for for-profit hospitals or surpluses for nonprofit hospitals.

Location of patients’ residence

Place of residence is based on the urban-rural classification scheme for U.S. counties developed by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) and based on the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) definition of a metropolitan service area as including a city and a population of at least 50,000 residents. For this Statistical Brief, we collapsed the NCHS categories into four groups according to the following:

Large Metropolitan

- Large Central Metropolitan: Counties in a metropolitan area with 1 million or more residents that satisfy at least one of the following criteria: (1) containing the entire population of the largest principal city of the metropolitan statistical area (MSA), (2) having their entire population contained within the largest principal city of the MSA, or (3) containing at least 250,000 residents of any principal city in the MSA

- Large Fringe Metropolitan: Counties in a metropolitan area with 1 million or more residents that do not qualify as large central metropolitan counties

Small Metropolitan

- Medium Metropolitan: Counties in a metropolitan area of 250,000–999,999 residents

- Small Metropolitan: Counties in a metropolitan area of 50,000–249,999 residents

Micropolitan:

- Micropolitan: Counties in a nonmetropolitan area of 10,000–49,999 residents

- Noncore: Counties in a nonmetropolitan and nonmicropolitan area

Community-level income

Community-level income is based on the median household income of the patient’s ZIP Code of residence. Quartiles are defined so that the total U.S. population is evenly distributed. Cut-offs for the quartiles are determined annually using ZIP Code demographic data obtained from Claritas, a vendor that produces population estimates and projections based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau. e The value ranges for the income quartiles vary by year. The income quartile is missing for patients who are homeless or foreign.

Expected payer

- Medicare: includes fee-for-service and managed care Medicare

- Medicaid: includes fee-for-service and managed care Medicaid

- Private insurance: includes commercial nongovernmental payers, regardless of the type of plan (e.g., private health maintenance organizations [HMOs], preferred provider organizations [PPOs])

- Self-pay/No charge: includes self-pay, no charge, charity, and no expected payment

- Other payers: includes other Federal and local government programs (e.g., TRICARE, CHAMPVA, Indian Health Service, Black Lung, Title V) and Workers’ Compensation

ED visits that were expected to be billed to the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) are included under Medicaid.

- Northeast: Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania

- Midwest: Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, and Kansas

- South: Delaware, Maryland, District of Columbia, Virginia, West Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas

- West: Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, Washington, Oregon, California, Alaska, and Hawaii

Discharge status

Discharge status reflects the disposition of the patient at discharge from the ED and includes the following categories reported in this Statistical Brief: routine (to home); admitted as an inpatient to the same hospital; transfers (transfer to another short-term hospital; other transfers including skilled nursing facility, intermediate care, and another type of facility such as a nursing home); and all other dispositions (home healthcare; against medical advice [AMA]; died in the ED; or destination unknown).

Hospital characteristics

Data on hospital ownership and status as a teaching hospital was obtained from the American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Survey of Hospitals. Hospital ownership/control includes categories for government nonfederal (public), private not-for-profit (voluntary), and private investor-owned (proprietary). Teaching hospital is defined as having a residency program approved by the American Medical Association, being a member of the Council of Teaching Hospitals, or having a ratio of full-time equivalent interns and residents to beds of 0.25 or higher.

Hospital trauma level

- Level I centers have comprehensive resources, are able to care for the most severely injured, and provide leadership in education and research.

- Level II centers have comprehensive resources and are able to care for the most severely injured, but do not provide leadership in education and research.

- Level III centers provide prompt assessment and resuscitation, emergency surgery, and, if needed, transfer to a level I or II center.

- Level IV/V centers provide trauma support in remote areas in which no higher level of care is available. These centers resuscitate and stabilize patients and arrange transfer to an appropriate trauma facility.

For this Statistical Brief, trauma hospitals were defined as those classified by the ASC/COT as a level I, II, or III trauma center. This is consistent with the classification of trauma centers used in the NEDS. The ACS/COT has a program that verifies hospitals as trauma level I, II, or III. h It is important to note that although all level I, II, and III trauma centers offer a high level of trauma care, there may be differences in the specific services and resources offered by hospitals of different levels. Trauma levels IV and V are designated at the State level (and not by ACS/COT) with varying criteria applied across States.

The Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP, pronounced "H-Cup") is a family of healthcare databases and related software tools and products developed through a Federal-State-Industry partnership and sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). HCUP databases bring together the data collection efforts of State data organizations, hospital associations, and private data organizations (HCUP Partners) and the Federal government to create a national information resource of encounter-level healthcare data. HCUP includes the largest collection of longitudinal hospital care data in the United States, with all-payer, encounter-level information beginning in 1988. These databases enable research on a broad range of health policy issues, including cost and quality of health services, medical practice patterns, access to healthcare programs, and outcomes of treatments at the national, State, and local market levels.

- Alaska Department of Health and Social Services

- Alaska State Hospital and Nursing Home Services Association

- Arizona Department of Health Services

- Arkansas Department of Health

- California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development

- Colorado Hospital Association

- Connecticut Hospital Association

- Delaware Division of Public Health

- District of Columbia Hospital Association

- Florida Agency for Health Care Administration

- Georgia Hospital Association

- Hawaii Laulima Data Alliance

- Hawaii University of Hawai’i at Hilo

- Illinois Department of Public Health

- Indiana Hospital Association

- Iowa Hospital Association

- Kansas Hospital Association

- Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services

- Louisiana Department of Health

- Maine Health Data Organization

- Maryland Health Services Cost Review Commission

- Massachusetts Center for Health Information and Analysis

- Michigan Health & Hospital Association

- Minnesota Hospital Association

- Mississippi State Department of Health

- Missouri Hospital Industry Data Institute

- Montana Hospital Association

- Nebraska Hospital Association Services

- Nevada Department of Health and Human

- New Hampshire Department of Health & Human

- New Jersey Department of Health

- New Mexico Department of Health

- New York State Department of Health

- North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services

- North Dakota (data provided by the Minnesota Hospital Association)

- Ohio Hospital Association

- Oklahoma State Department of Health

- Oregon Association of Hospitals and Health Systems

- Oregon Office of Health Analytics

- Pennsylvania Health Care Cost Containment Council

- Rhode Island Department of Health

- South Carolina Revenue and Fiscal Affairs Office

- South Dakota Association of Healthcare Organizations

- Tennessee Hospital Association

- Texas Department of State Health Services

- Utah Department of Health

- Vermont Association of Hospitals and Health Systems

- Virginia Health Information

- Washington State Department of Health

- West Virginia Department of Health and Human Resources, West Virginia Health Care Authority

- Wisconsin Department of Health Services

- Wyoming Hospital Association

- About the NEDS

The HCUP Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS) is a unique and powerful database that yields national estimates of emergency department (ED) visits. The NEDS was constructed using records from both the HCUP State Emergency Department Databases (SEDD) and the State Inpatient Databases (SID). The SEDD capture information on ED visits that do not result in an admission (i.e., patients who were treated in the ED and then released from the ED, or patients who were transferred to another hospital); the SID contain information on patients initially seen in the ED and then admitted to the same hospital. The NEDS was created to enable analyses of ED utilization patterns and support public health professionals, administrators, policymakers, and clinicians in their decision making regarding this critical source of care. The NEDS is produced annually beginning in 2006. Over time, the sampling frame for the NEDS has changed; thus, the number of States contributing to the NEDS varies from year to year. The NEDS is intended for national estimates only; no State-level estimates can be produced. The unweighted sample size for the 2017 NEDS is 33,506,645 (weighted, this represents 144,814,803 ED visits).

- For More Information

For other information on emergency department visits, refer to the HCUP Statistical Briefs located at www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb_ed.jsp .

- HCUP Fast Stats at www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/faststats/landing.jsp for easy access to the latest HCUP-based statistics for healthcare information topics

- HCUPnet, HCUP’s interactive query system, at www.hcupnet.ahrq.gov/

For more information about HCUP, visit www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/ .

For a detailed description of HCUP and more information on the design of the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS), please refer to the following database documentation:

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Overview of the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS). Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Updated December 2019. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nedsoverview.jsp . Accessed February 3, 2020.

- Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Nils Nordstrand of IBM Watson Health.

The HCUP Cost-to-Charge Ratios (CCRs) for NEDS Files were not publicly available at the time of publication, so an internal version was used in this Statistical Brief.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HCUP Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS) Database Documentation. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Updated April 27, 2020. www .hcup-us.ahrq.gov /db/nation/neds/nedsdbdocumentation.jsp . Accessed October 27, 2020.

For additional information about the NHEA, see Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). National Health Expenditure Data. CMS website. Updated December 17, 2019. www .cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems /Statistics-Trends-and-Reports /NationalHealthExpendData/index .html?redirect= /NationalHealthExpendData/ . Accessed February 3, 2020.

American Hospital Association. TrendWatch Chartbook, 2019. Table 4.2. Distribution of Inpatient vs. Outpatient Revenues, 1995–2017. www .aha.org/system/files /media/file/2019 /11/TrendwatchChartbook-2019-Appendices .pdf . Accessed March 19, 2020.

Claritas. Claritas Demographic Profile by ZIP Code. https://claritas360.claritas.com/mybestsegments/. Accessed February 3, 2020.

American Trauma Society. Trauma Information Exchange Program (TIEP). www .amtrauma.org/page/TIEP . Accessed June 11, 2020.

MacKenzie EJ, Hoyt DB, Sacra JC, Jurkovich GJ, Carlini AR, Teitelbaum SD, et al. National inventory of hospital trauma centers. JAMA. 2003;289(12):1515–22. [ PubMed : 12672768 ]

American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma, Verification, Review, and Consultation Program for Hospitals. Additional details are available at www .facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/vrc . Accessed July 17, 2020.

Moore BJ (IBM Watson Health), Liang L (AHRQ). Costs of Emergency Department Visits in the United States, 2017. HCUP Statistical Brief #268. December 2020. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb268-ED-Costs-2017.pdf .

- Cite this Page Moore BJ, Liang L. Costs of Emergency Department Visits in the United States, 2017. 2020 Dec 8. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2006 Feb-. Statistical Brief #268.

- PDF version of this page (326K)

In this Page

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP)

- Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS)

- Kids' Inpatient Database (KID)

- Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS)

- State Inpatient Databases (SID)

- State Ambulatory Surgery Databases (SASD)

- State Emergency Department Databases (SEDD)

- HCUP Overview

- HCUP Fact Sheet

- HCUP Partners

- HCUP User Support

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- Review Costs of Emergency Department Visits for Mental and Substance Use Disorders in the United States, 2017. [Healthcare Cost and Utilizatio...] Review Costs of Emergency Department Visits for Mental and Substance Use Disorders in the United States, 2017. Karaca Z, Moore BJ. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. 2006 Feb

- Review Expected Payers and Patient Characteristics of Maternal Emergency Department Care, 2019. [Healthcare Cost and Utilizatio...] Review Expected Payers and Patient Characteristics of Maternal Emergency Department Care, 2019. McDermott KW, Reid LD, Owens PL. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. 2006 Feb

- Review Emergency Department Visits Involving Dental Conditions, 2018. [Healthcare Cost and Utilizatio...] Review Emergency Department Visits Involving Dental Conditions, 2018. Owens PL, Manski RJ, Weiss AJ. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. 2006 Feb

- Review Overview of Emergency Department Visits Related to Injuries, by Cause of Injury, 2017. [Healthcare Cost and Utilizatio...] Review Overview of Emergency Department Visits Related to Injuries, by Cause of Injury, 2017. Weiss AJ, Reid LD, Barrett ML. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. 2006 Feb

- Review Racial and Ethnic Differences in Emergency Department Visits Related to Substance Use Disorders, 2019. [Healthcare Cost and Utilizatio...] Review Racial and Ethnic Differences in Emergency Department Visits Related to Substance Use Disorders, 2019. Owens PL, Moore BJ. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. 2006 Feb

Recent Activity

- Costs of Emergency Department Visits in the United States, 2017 - Healthcare Cos... Costs of Emergency Department Visits in the United States, 2017 - Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

The Costs of US Emergency Department Visits

The US population made 144.8 million emergency department (ED) visits in 2017, costing a total of $76.3 billion, estimated a recent statistical brief from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP).

That year, 13.3% of the US population incurred an expense for an ED visit, and more than half of hospital inpatient stays originated with an ED visit. More than half of 2017 ED costs for the entire US, $39.5 billion, were incurred in large metropolitan areas. Aggregate ED visit costs and share of ED visit volume were highest for hospitals in the South. (ED charges were converted to costs using HCUP Cost-to-Charge Ratios based on Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services hospital accounting reports.)

Read More About

Rubin R. The Costs of US Emergency Department Visits. JAMA. 2021;325(4):333. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.26936

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Cardiology in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine