The Ages of Exploration

Samuel de champlain, age of discovery.

Quick Facts:

French explorer and cartographer best known for establishing and governing settlements in Canada, mapping the St. Lawrence River, discovering the Great Lakes, and founding the city of Quebec

Name : Samuel de Champlain [sam-yoo-uh l; (French) sa-my-el ] [ duh] [sham-pleyn; (French) shahn-plan]

Birth/Death : ca. 1567 - December 25, 1635

Nationality : French

Birthplace : Brouage, France

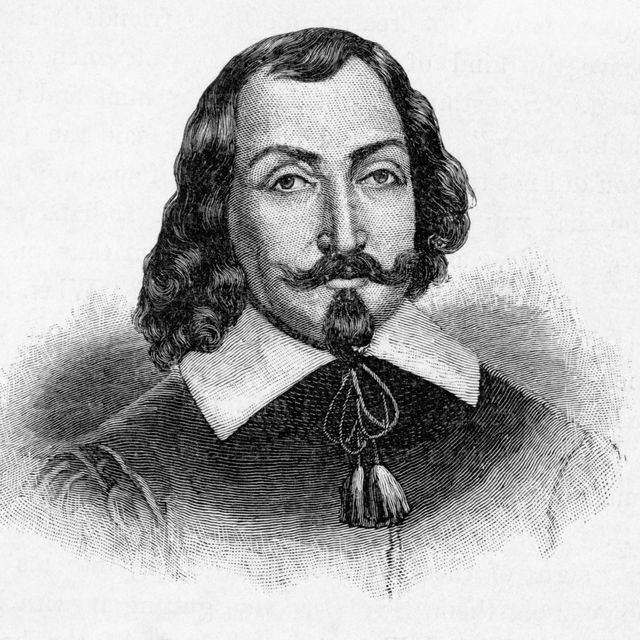

Samuel de Champlain (1567-1635), most likely styled after a portrait by Moncornet, 19th century. Source: A Popular History of France from the Earliest Times, Vol. 6, Chapter 53, p. 190. {{PD-Art}

Introduction Samuel de Champlain was a French explorer famous for his journeys in modern day Canada. During his travels, he mapped the Atlantic coast of Canada, parts of the St. Lawrence River, and parts of the Great Lakes. He is best known for establishing the first French settlement in the Canadian territory, and founding the city of Quebec. Because of this, Champlain became known as the “Father of New France.” 1

Biography Early Life Samuel de Champlain was born in the French village Brouage in the Province of Saintonge. Historians do not know his exact date of birth, but most agree it was between 1567 and 1570. 2 His father was Antoine Champlain and his mother was Marguerite Le Roy. Brouage was a seaport town where Antoine Champlain was a sea captain in the merchant marine. 3 Samuel de Champlain probably would have had a modest education where he learned to read and write. But his real skill was navigation. He went to sea at a young age, and learned to navigate, draw, and make nautical charts. During this time period, the French were at war against the Spanish. In 1593, Champlain served in the army of Henry of Navarre – also known as King Henry IV of France. He served in the army for 5 years, until King Henry’s and France’s victory in 1598. When the war ended, Champlain joined his uncle, Captain Provençal, on a mission from the King to return any captured Spanish soldiers to Spain.

Champlain and Provençal, along with their crew and captured Spanish soldiers, left France aboard the St. Julien September 9, 1598. They delivered the soldiers to Spain, but did not return back to France. Instead, the Spanish government hired Provençal and Champlain for a trip to its colonies in the West Indies (the Caribbean region). They accepted, and between 1599 and 1601, Champlain made three voyages for Spain to her American colonies. During these years, he visited several places, including the Virgin Islands and other Caribbean islands, Puerto Rico, Mexico, and Panama. Along the way he recorded much of his journey. In 1601, he wrote a detailed report to King Henry about his trip, which included maps, and drawings of plants and animals. He even mentioned the idea of a canal that should cut through Panama to connect the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. 4 300 years later, this would be seen in the creation of the Panama canal. The King was impressed with Champlain’s descriptions. King Henry IV wanted to the French to begin settling in the New World in hopes that wealth could be brought back to France. So he sent an expedition to locate a place in the New World to establish a French colony and fur trade settlement. Samuel de Champlain would be among the men who would take part in this venture.

Voyages Principal Voyage Samuel de Champlain would take his second New World voyage under the expedition of François Gravé Du Pont. The fleet set sail from France on March 15, 1603. They crossed the Atlantic Ocean and arrived in North America. They continued past Newfoundland, entered the St. Lawrence River. They anchored in the harbor of Tadoussac near the mouth of the Saguenay River on May 26, 1603. 5 While here, the French interacted with some of the natives, and Champlain recorded the customs and interactions of these people. The expedition soon continued up the St. Lawrence River, and made it as far as present day Montréal. The native guides that had helped the Frenchmen spoke of a great sea to the west. Champlain hoped this sea to be the Pacific Ocean and the Northwest Passage to Asia. However, due to the strong rapids, the French were unable to explore much further. It would later be known that the “sea” the natives referred to were the Great Lakes. 6 Champlain continued to explore and interactive with the different native tribes, which included the Algonquin, Montagnais, and Hurons. The expedition ended when they returned to France in September 1603.

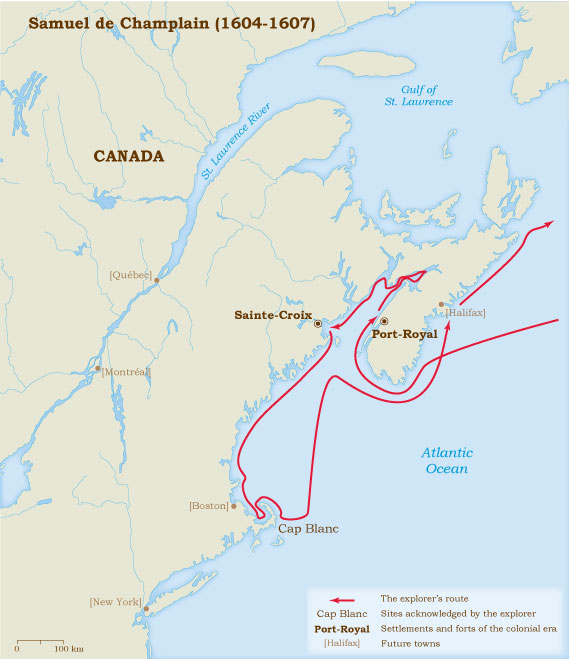

In France, Champlain reported the details of his trip to the King. By 1604, Champlain was once more heading to the New World. This time the expedition was led by Pierre du Gua de Monts. De Monts had been granted monopoly – exclusive possession – of the fur trade. They would spend the next three years exploring and mapping parts of North America. The expedition set sail on three ships, including La Bonne Renommée and Don de Dieu which Champlain sailed on. The goal was to once again try to find a good place for a French settlement. They landed on the coast of Nova Scotia, sailed around to the Bay of Fundy. 7 The expedition focused much its efforts on areas south of the St. Lawrence River. After a few months, they settled for winter at Saint Croix Island in the St. Croix River. After enduring a harsh winter, they began exploring the eastern coastline as far down as Cape Cod. In 1605, they established their first successful settlement – Port Royal (now known as Annapolis Royal) in Nova Scotia. In 1606, this site would become the capital of the area known as Acadia. Du Gua had to return to France in September 1605. His company was having financial hardship. Champlain and the expedition continued exploring these areas for the next few years. In July 1607, du Gua’s fur trade monopoly ended. Port Royal was forced to end, and Champlain and the settlers returned to France. 8

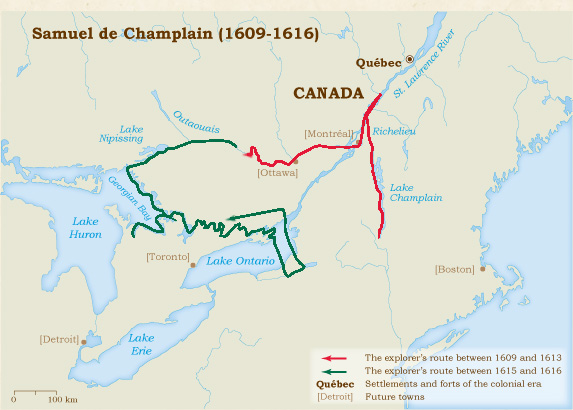

Subsequent Voyages In 1608, Champlain was chosen as du Gua’s lieutenant on another expedition across the Atlantic. Champlain left France on April 13, 1608 and headed for the St. Lawrence river. Once again, the goal was to start a new French colony. Champlain found an area on the shores of the St. Lawrence river and began constructing a fort and other buildings. In July 1608, Samuel de Champlain and his men created the first successful French colony in New France. The site of the colony was at a place the native Indians called kebec which means “ the narrowing of the waters.” 9 Champlain and the French spelled it Quebec. During the very harsh winter here, several of the men died of scurvy. In the summer of 1609, Champlain planned to head west further inland to explore and map the land. Before he could go, the Algonquins and Huron natives asked Champlain to help them attack the powerful Iroquois tribe. He joined them, and on July 29, they all defeated the Iroquois army. This expedition also enabled Champlain to explore the Richelieu River and to become the first European to map Lake Champlain. This battle would lead to several years of hostility between the French and Iroquois natives. With the death of King Henry, however, Champlain returned to France to discuss his political future.

Champlain returned to France and reported the success of creating the settlement of Quebec. It was decided that it would be the center for the French fur trade. Champlain returned to New France and Quebec many times over the next several years where he went on to explore and map much of the land. In 1610, he fought against the Iroquois once again. In spring 1611, he sailed up the St. Lawrence river and made it as far as present day Montreal. When he returned to France, the King chose Champlain to be his lieutenant in New France. 10 He was back in Quebec by March 1613. This time he went as far as the Ottawa River and explored areas connected to the Great Lakes. In 1615, he traveled up the Ottawa River to Lake Nipissing and the French River. He saw the Great Lakes for the first time when he arrived at Georgian Bay on the east side of Lake Huron. 11 When he returned to France, Champlain’s position as lieutenant in New France was taken away. This discovery would be his last great voyage of exploration. He would spend the next years of his life trying to re-establish and maintain his authority in New France.

Later Years and Death Samuel de Champlain returned to France in July 1616 where he learned his title of lieutenant had been taken away. He suggested to the French King that they begin growing the colony of Quebec. The King agreed, and Champlain returned to New France again in 1620. He spent the rest of his life focusing on governing and growing the territory rather than exploration. In 1628, Champlain became the deputy of the “Company One Hundred Associates” organized by Cardinal Richelieu to colonize New France. The company was given all the lands between Florida and the Arctic Circle, with a monopoly of trade with the exception of cod and whale fisheries. The Quebec colony had continued problems from the natives. In 1629 Champlain was forced to surrender Quebec to the English until 1632 when the colony was returned to France. In 1633, Champlain returned to Quebec where he continued to serve as governor. As he grew older, he became ill in late 1635. Champlain died in Quebec on Christmas Day – December 25, 1635.

Legacy Samuel de Champlain is remembered as one of the greatest pioneers of French expansion in the 17th century. He formed several settlements, including Acadia and Quebec City. He also mapped and explored much of the region. His travels enabled France to gain control on the North American continent and form the country of Canada. Champlain wrote down and left behind his writings related to his voyages. His accounts described many areas he explored, indigenous peoples, local plants and animals, and numerous maps. Champlain is honored throughout Canada. Many places bear his name, including Lake Champlain. But his legacy is best seen in the city of Quebec. By the time of Champlain’s death, there were almost 300 French pioneers living in New France. 12 Now, they have a population of over 7 million people. 13 Quebec City continues to be a thriving area and is the capital of the Quebec Province in Canada still today.

- Adrianna Morganelli, Samuel de Champlain: From New France to Cape Cod (New York: Crabtree Publishing Company, 2006), 4.

- Josepha Sherman, Samuel de Champlain, Explorer of the Great Lakes Region and Founder of Quebec (New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc., 2003), 7.

- Sherman, Samuel de Champlain , 7.

- Harold Faber, Samuel de Champlain, Explorer of Canada (New York: Benchmark Books, 2005), 10.

- Daniel B. Baker, ed., Explorers and Discoverers of the World (Detroit: Gale Research, Inc., 1993), 131.

- Morganelli, Samuel de Champlain , 10.

- Baker, Explorers and Discoverers of the World , 131.

- Raymonde Litalien and Denis Vaugeois, eds., Champlain: The Birth of French America (Canada: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2004), 146.

- Richard E. Bohlander, ed., World Explorers and Discoverers (New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1992), 106.

- Baker, Explorers and Discoverers of the World , 132.

- Bohlander, World Explorers and Discoverers , 108.

- Francois Remillard and Ulysses Travel Guides, Quebec (Montreal: Hunter Publishing, Inc., 2003), 13.

- Remillard and Ulysses Travel Guides, Quebec , 25.

- The Mariners' Educational Programs

- Bibliography

Library and Archives Canada Blog

This is the official blog of library and archives canada (lac)..

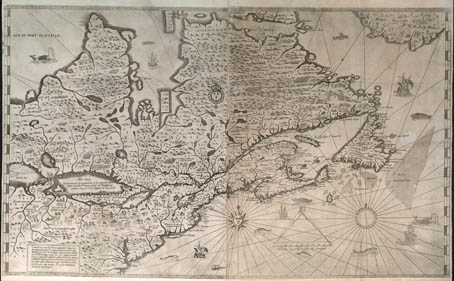

Samuel de Champlain’s General Maps of New France

In the fall of 1612, Samuel de Champlain had an engraving of his first detailed map of New France made in Paris. The map contained new geographic information, based on his own explorations from 1603 onward. The site of Montreal is clearly identified. Using information obtained from Aboriginal peoples, he was able to include previously uncharted areas, such as Lake Ontario and Niagara Falls. He also made use of other maps to depict certain regions, including Newfoundland. Although the engraving was made in 1612, the map was not published until the following year as an appendix to Voyages , Champlain’s 1613 account of his journeys.

Carte geographique de la Nouvelle Franse faictte par le sieur de Champlain Saint Tongois cappitaine ordinaire pour le roy en la marine. Faict len 1612. (e010764733)

While back in France in the summer of 1613, Champlain had an engraving made of a second version of a general map that he had begun the previous year, which he also published in his 1613 book. In that map, he incorporated his most recent geographic findings, including the Ottawa River, which he was the first to depict. His depiction of Hudson Bay was deliberately inspired by a map of Henry Hudson’s voyages.

Carte geographique de la Nouvelle Franse en son vray meridiein. Faictte par le Sr Champlain, Cappine. por le Roy en la marine – 1613. ( e010764734 )

An incomplete general map by Champlain also exists. The engraving was made in 1616, although the map was never published. The only known copy is held by the John Carter Brown Library .

In 1632, Champlain published his last major map of New France, which was included in his final book, Les Voyages de la Nouvelle France occidentale, dicte Canada . He had been living in France for nearly three years, having been driven out of Quebec by the Kirke brothers in 1629. This updated map contains little new information verified by Champlain himself, as his own explorations came to an end in 1616. He based the revised version on the invaluable information conveyed to him by others, chief among them Étienne Brûlé. Nevertheless, this map represents an important milestone in the history of North American cartography and was widely used by other mapmakers. There are two versions of this map. Among the differences between them are the representation of Bras d’Or Lake or a chain of mountains on Cape Breton Island. Both versions of the map are held by Library and Archives Canada. The first can be seen here:

Carte de la Nouvelle France, augmentée depuis la derniere, servant a la navigation faicte en son vray meridien, 1632. (e010771375)

Suggested reading to learn more about this subject: Conrad E. Heidenreich and Edward H. Dahl, “Samuel de Champlain’s Cartography, 1603-32”, in Raymonde Litalien and Denis Vaugeois, eds., Champlain: The Birth of French America . Sillery: Les éditions du Septentrion; and Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2004, pp. 312-332.

Share this:

8 thoughts on “ samuel de champlain’s general maps of new france ”.

Reblogged this on Bite Size Canada and commented: Champlain’s maps and more! Great blog, too, btw! – tk

I agree with tkmorin, but what’s not to like about historic cartography? I enjoy the extraneous and obscure but helpful decoration historic maps tended to have.

Pingback: Advertising New France | All About Canadian History

Champlain’s family background (in french).

https://pierredubeaublog.wordpress.com/2017/03/28/les-origines-nobles-de-la-famille-de-samuel-de-champlain/

Champlain family’s background.

Pingback: Teaching the Politics and Meaning of Maps | Borealia

I have a tremendous fascination with historical maps like this. I have several copies of maps of New Orleans where I live and continue mapping to this day.

Thankk you for sharing

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Samuel de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain was a French explorer and cartographer best known for establishing and governing the settlements of New France and the city of Quebec.

Who Was Samuel de Champlain?

French explorer Samuel de Champlain began exploring North America in 1603, establishing the city of Quebec in the northern colony of New France, and mapping the Atlantic coast and the Great Lakes, before settling into an administrative role as the de facto governor of New France in 1620.

Samuel de Champlain was born in 1574 (according to his baptismal certificate, which was discovered in 2012), in Brouage, a small port town in the province of Saintonge, on the western coast of France. Although Champlain wrote extensively of his voyages and later life, little is known of his childhood. He was likely born a Protestant, but converted to Catholicism as a young adult.

First Explorations and Voyages

Champlain's earliest travels were with his uncle, and he ventured as far as Spain and the West Indies. From 1601 to 1603, he was a geographer for King Henry IV, and then joined François Gravé Du Pont's expedition to Canada in 1603. The group sailed up the St. Lawrence and Saguenay rivers and explored the Gaspé Peninsula, ultimately arriving in Montreal. Although Champlain had no official role or title on the expedition, he proved his mettle by making uncanny predictions about the network of lakes and other geographic features of the region.

Given his usefulness on Du Pont's voyage, the following year Champlain was chosen to be geographer on an expedition to Acadia led by Lieutenant-General Pierre Du Gua de Monts. They landed in May on the southeast coast of what is now Nova Scotia and Champlain was asked to choose a location for a temporary settlement. He explored the Bay of Fundy and St. John River area before selecting a small island in the St. Croix River. The team built a fort and spent the winter there.

In the summer of 1605, the team sailed down the coast of New England as far south as Cape Cod. Although a few British explorers had navigated the terrain before, Champlain was the first to give a precise and detailed accounting of the region that would one day become Plymouth Rock.

Establishing Quebec

In 1608, Champlain was named lieutenant to de Monts, and they set off on another expedition up the St. Lawrence. When they arrived in June 1608, they constructed a fort in what is now Quebec City. Quebec would soon become the hub for French fur trading. The following summer, Champlain fought the first major battle against the Iroquois, cementing a hostile relationship that would last for more than a century.

In 1615, Champlain made a brave voyage into the interior of Canada accompanied by a tribe of Native Americans with whom he had good relations, the Hurons. Champlain and the French aided the Hurons in an attack on the Iroquois, but they lost the battle and Champlain was hit in the knee with an arrow and unable to walk. He lived with the Hurons that winter, between the foot of Georgian Bay and Lake Simcoe. During his stay, he composed one of the earliest and most detailed accounts of Native American life.

Later Years and Death

When Champlain returned to France, he found himself embroiled in lawsuits and was unable to return to Quebec. He spent this time writing the stories of his voyages, complete with maps and illustrations. When he was reinstated as lieutenant, he returned to Canada with his wife, who was 30 years his junior. In 1627, Louis XIII's chief minister, Cardinal de Richelieu, formed the Company of 100 Associates to rule New France and placed Champlain in charge.

Things didn't go smoothly for Champlain for long. Eager to capitalize on the profitable fur trade in the region, Charles I of England commissioned an expedition under David Kirke to displace the French. They attacked the fort and seized supply ships, cutting off necessities to the colony. Champlain surrendered on July 19, 1629 and returned to France.

Champlain spent some time writing about his travels until, in 1632, the British and the French signed the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, returning Quebec to the French. Champlain returned to be its governor. By this time, however, his health was failing and he was forced to retire in 1633. He died in Quebec on Christmas Day in 1635.

Related Videos

Quick facts.

- Name: Samuel de Champlain

- Birth City: Brouage, Province of Saintonge

- Birth Country: France

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Samuel de Champlain was a French explorer and cartographer best known for establishing and governing the settlements of New France and the city of Quebec.

- Politics and Government

- War and Militaries

- Technology and Engineering

- Nacionalities

- Death Year: 1635

- Death date: December 25, 1635

- Death City: Quebec

- Death Country: Canada

- The advice I give to all adventurers is to seek a place where they may sleep in safety.

Watch Next .css-16toot1:after{background-color:#262626;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

European Explorers

Christopher Columbus

10 Famous Explorers Who Connected the World

Sir Walter Raleigh

Ferdinand Magellan

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo

Leif Eriksson

Vasco da Gama

Bartolomeu Dias

Giovanni da Verrazzano

Jacques Marquette

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

About the Film

Broadcast schedule.

- The Journey

- Behind the Scenes

In the Footsteps of Champlain

Animation gallery, media coverage, story elements, the filmmakers, the animators, sound designers, the scholars, educational outreach, lesson plans, champlain timeline, champlain's soundtrack.

- Buy the DVD

Samuel de Champlain first arrived in what is now Canada in May 1603. Over the next thirteen years, he made seven trips into the interior, forging trade alliances with multiple tribes, accompanying them in their wars against the Iroquois, building Québec, and collecting geographic information for his maps and journals. All of his travels were dependent on the knowledge, skills, and technologies of the Algonquin, Wendat, Wabanaki and Innu. These travels formed the basis for his published journals, Les Savauges and Les Voyages .

This map allows you to follow in the footsteps of Champlain, discovering along the way entries from his journals, Amerindian location names, clips from Dead Reckoning ~ Champlain in America , and lesson plans that teachers and students can download to enhance the study of the life and times of Samuel de Champlain.

Lauch the map

Map credits.

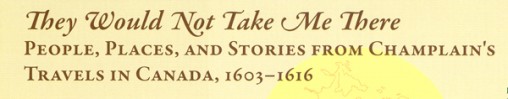

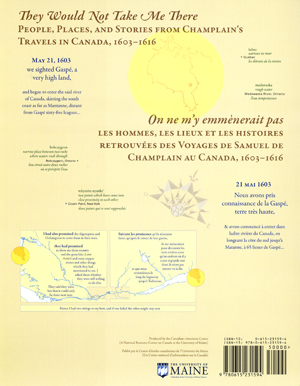

The map, They Would Not Take Me There: People, Places, and Stories from Champlain's Travels in Canada, 1603 - 1616, was produced by the Canadian-American Center: A National Resource Center on Canada located at the University of Maine; Stephen J. Hornsby, Director.

The Authors/Cartographers are Michael J. Hermann and Margaret W. Pearce. Translator: Raymond J. Pelletier

© 2008 University of Maine Canadian–American Center, Orono, Maine, USA

For more information on the making of the interactive map, go to: www.umaine.edu/canam/cartography/Champlain.html

www.umaine.edu

The quotes from Champlain’s journals are from the translation edited by Henry Percival Biggar, The works of Samuel de Champlain, 6 v. Toronto: Champlain Society, 1922–36, rep. 1976. The authors also drew on the following books for historical and cartographic interpretations of Champlain’s story:

Heidenreich, Conrad E. 1976. Explorations and mapping of Samuel de Champlain, 1603–1632. Cartographica monograph no. 17. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Litalien, Raymonde and Vaugeois, Denis, eds. 2004. Champlain: The birth of French America. Montreal: McGill–Queen’s University Press.

Trigger, Bruce G. 1976. The Children of Aataentsic: A history of the Huron people to 1660. Montreal: McGill–Queen’s University Press.

The authors also drew on many more sources for Native place names and village locations.

A complete bibliography and place name database can be found at the website www.umaine.edu/canam

SPECIAL THANKS TO

Neil Allen, Betsy Arntzen, Nahanni Born, Hans Carlson, Abigail Davis, James Eric Francis, Sr., Robin Harrington, Conrad Heidenreich, Nicole Henderson, Stephen J. Hornsby, Douglas Jack, Anne Knowles, Micah Pawling, Raymond Pelletier, Sam Pepple, Kathryn Slott, Jane Smith, Nancy Strayer, and Roy Wright

Major funding provided by

Funding for the French website provided by

- Apply to UMaine

Canadian-American Center

Champlain map: “they would not take me there”.

Award-winning EXPLANATORY MAP produced by the Canadian-American Center, illustrates the travels of Samuel de Champlain as he explored what is now Canada, seeking a route between the St. Lawrence River and James Bay.

Authors/Cartographers: Michael James Hermann & Margaret Wickens Pearce Translator : Raymond Pelletier

- Specifications

- Reading the Map: image of entire map

- How the Cartographers Made the Map

- Cartographers’ Use of Color

- Links to Publicity

- Bibliography of Native Place Names

Description :

This map, produced by the Canadian-American Center, illustrates the travels of Samuel de Champlain as he explored Canada between 1603 and 1616. During those thirteen years, Champlain made seven trips into the interior, forging trade alliances with multiple First Nations, accompanying them in their wars against the Iroquois, building Québec, and collecting geographic information for his maps and journals. These travels were dependent on the knowledge, skills, and technologies of the Algonquin, Wendat, Wabanaki, and Innu which formed the basis for his published journals, Les Savauges and Les Voyages .

Although Champlain’s attention encompassed a range of economic, religious, and colonial interests, his written accounts suggest a personal passion for finding the connection between the St. Lawrence River and what is now James Bay. Drawing on Biggar’s edition of Champlain’s journals ( The Works of Samuel de Champlain , H.P. Biggar, ed. 1922-36), Trigger’s ethnohistorical Huron study, (The Children of Aataentsic: A History of the Huron People to 1660, Bruce G. Trigger, 1987) , and numerous linguistic and geographical references, this cartographic work weaves together Native and non-Native experiences, negotiations, and strategies in the years before the creation of Québec City and New France.

The Cartographers’ Voices :

“ At one level, Champlain’s explorations have been extensively documented and mapped by scholars focusing on the locations and dates of Champlain’s arrivals and departures. But these maps are silent with regard to the Indigenous geographies through which Champlain moved and upon which he relied for the success of his own explorations and mappings. Also, they fail to convey the human experiences which shape the emotional geographies of his journals.” – MWPearce and MJHermann

English on one side: They Would Not Take Me There; People, Places and Stories from Champlain’s Travels in Canada, 1603-1616

Français de l’autre côté: Les hommes, les lieux, et les histoires retrouvées des Voyages de Samuel de Champlain au Canada, 1603-1616

Measurements : Flat: 39 x 59 inches Folded: 8 x 10 inches Available rolled or folded

ISBN 978-0615-23159-4

Publisher: The University of Maine Canadian–American Center Orono, Maine, USA

Price (US): Retail: $14.99 Educational use: $10.00 Plus postage

- For Students

- Publications

- Grant Opportunities

- K-12 Educator Resources

Search The Canadian Encyclopedia

Enter your search term

Why sign up?

Signing up enhances your TCE experience with the ability to save items to your personal reading list, and access the interactive map.

- MLA 8TH EDITION

- Trudel, Marcel and Mathieu d'Avignon. "Samuel de Champlain". The Canadian Encyclopedia , 11 June 2021, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/samuel-de-champlain. Accessed 29 August 2024.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , 11 June 2021, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/samuel-de-champlain. Accessed 29 August 2024." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- APA 6TH EDITION

- Trudel, M., & d'Avignon, M. (2021). Samuel de Champlain. In The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/samuel-de-champlain

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/samuel-de-champlain" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- CHICAGO 17TH EDITION

- Trudel, Marcel , and Mathieu d'Avignon. "Samuel de Champlain." The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published August 29, 2013; Last Edited June 11, 2021.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published August 29, 2013; Last Edited June 11, 2021." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- TURABIAN 8TH EDITION

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "Samuel de Champlain," by Marcel Trudel, and Mathieu d'Avignon, Accessed August 29, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/samuel-de-champlain

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "Samuel de Champlain," by Marcel Trudel, and Mathieu d'Avignon, Accessed August 29, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/samuel-de-champlain" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

Thank you for your submission

Our team will be reviewing your submission and get back to you with any further questions.

Thanks for contributing to The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Samuel de Champlain

Article by Marcel Trudel , Mathieu d'Avignon

Updated by Tabitha Marshall, Andrew McIntosh

Published Online August 29, 2013

Last Edited June 11, 2021

Samuel de Champlain, cartographer, explorer, colonial administrator, author (born circa 1567 in Brouage, France; died 25 December 1635 in Quebec City). Known as the “Father of New France,” Samuel de Champlain played a major role in establishing New France from 1603 to 1635. He is also credited with founding Quebec City in 1608. He explored the Atlantic coastline (in Acadia ), the Canadian interior and the Great Lakes region. He also helped found French colonies in Acadia and at Trois-Rivières , and he established friendly relations and alliances with many First Nations , including the Montagnais , the Huron , the Odawa and the Nipissing. For many years, he was the chief person responsible for administrating the colony of New France. Champlain published four books as well as several maps of North America. His works are the only written account of New France at the beginning of the 17th century.

Early Life and Career

There is no authentic portrait of Champlain and little is known about his family background or youth. He may have been baptized a Protestant . It is certain, however, that he was a Catholic as of 1603.

In 1613, he wrote that he was interested “from a very young age in the art of navigation , along with a love of the high seas.” By the age of 20, he had sailed to Spain, the Caribbean and South America. The account of these voyages, Bref Discours , is attributed to him, but he himself never referred to it.

First Voyages to Canada

Champlain landed in Canada in 1603, on a voyage up the St. Lawrence River with François Gravé du Pont. At the time, Champlain held no official title. He published an account of this voyage, Des Sauvages, ou, Voyage de Samuel Champlain , in France. It was the first detailed description of the St. Lawrence since Jacques Cartier ’s explorations. Since that time, the Algonquin had taken over the area from the Iroquois . At Tadoussac and other locations in the Laurentian Valley, the French had contact primarily with the Montagnais , Algonquin, Maliseet and Mikmaq peoples.

In 1604, Champlain sailed to Acadia with Pierre Dugua de Mons , who planned to establish a French colony there. Champlain had no position of command at either of the Acadian settlements at Ste-Croix or Port-Royal (now Annapolis Royal , Nova Scotia ). As a cartographer , he was tasked with searching the coast for an ideal location for settlement. He also acted as a diplomat in dealings with the Indigenous peoples that Dugua wanted to get to know better.

In 1605 and again in 1606, Champlain explored the coastline of what is now New England. He went as far south as Cape Cod. In 1608, Dugua chose the St. Lawrence over Acadia. He sent Champlain to establish a settlement at Quebec (now Quebec City ), where the fur trade with First Nations could be controlled more easily.

Settlement at Quebec

In 1608, Pierre Dugua de Mons appointed Champlain as his lieutenant; this was his first official title. On 13 April 1608, Champlain set sail from France in Le Don de Dieu . He reached Tadoussac on 3 June. He then resumed his course up the St. Lawrence , arriving off Cap Diamant on 3 July. Champlain later wrote, “I searched for a place suitable for our settlement, but I could find none more convenient or better situated than the point of Quebec.”

Champlain set the men to work felling trees and sawing the logs into boards. They dug ditches and constructed a storehouse and cellar. The settlement included another three main buildings; these two-storey structures were the men’s living quarters. A gallery ran around the outside of the buildings on the second floor. The settlement was protected by ditches, stockades and cannons.

Before the work was done, Champlain had to put down a mutiny led by locksmith Jean Duval. The plan was to murder Champlain and turn over the fort “to the Basques or Spaniards, then at Tadoussac.” One of the men, however, changed his mind and told Champlain, who arrested the conspirators. Duval was executed, his head stuck on a pike as a warning. The others were sent to France.

After the crisis, work resumed. Land was cleared and planted with winter wheat and rye . Despite their preparations, the men suffered that winter from severe scurvy. Sixteen of 25 men died, including the surgeon.

Champlain and the few survivors received fresh supplies in April 1609. In June, he set off on an expedition, accompanied by two Frenchmen and a party of Wendat (Huron), Algonquin and Montagnais. The group reached a great lake, which would be named in his honour ( see Lake Champlain .) In late July, they encountered a party of Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) at Ticonderoga . According to historian Marcel Trudel, Champlain killed two men during the engagement. Not long after, he sailed to France, leaving Pierre Chavin in command of Quebec. Champlain returned the following spring.

Champlain vowed to make Quebec the centre of a powerful colony. However, he was opposed by the various merchant companies that employed him. It was more profitable for them to be involved only in the fur trade . In a 1618 report, Champlain outlined Quebec’s commercial, industrial and agricultural opportunities. His dream seemed about to come true in 1627 when the Compagnie des Cent-Associés was founded. By 1628, however, the Kirke brothers had taken over Tadoussac , Cap Tourmente, and Quebec in the name of the English Crown . The capital of the fledgling colony of New France was also taken by the English in 1629. Champlain was taken prisoner and sent to England. He and Quebec were returned to the French under the Treaty of Saint-Germain in 1632.

Appointed lieutenant by Cardinal Richelieu, Champlain returned to Quebec in 1633. He was able to see the promising beginnings of the colony he had planned. He was paralyzed in the fall of 1635 due to a stroke. He died on Christmas Day that year. His remains, buried under the Champlain chapel which adjoined Notre-Dame-de-la-Recouvrance, may today lie under the cathedral basilica, Notre-Dame de Québec .

Relationship with Indigenous People

Champlain developed a vast trade network by forming and consolidating alliances with the Montagnais of the St. Lawrence , the nations on the Ottawa River , and the Huron of the Great Lakes . These alliances obliged Champlain to support his allies in their wars against the Iroquois , whose territory was to the south of Lake Ontario and into present-day New York. He participated in military campaigns in 1609 (on Lake Champlain ), in 1610 (near Sorel ) and in 1615 (in Iroquois territory). Injured in the third expedition, he was forced to spend the winter of 1615—16 in Huronia . He took advantage of this time to explore the Lake Huron region. He also developed cordial relations with other nations, notably the Odawa and the Nipissing. ( See also Indigenous-French Relations .)

Champlain’s Writings

Champlain left behind a considerable body of writing, largely relating to his voyages. The most important editions of his work are the ones prepared by C.H. Laverdière (1870) and the bilingual edition of H.P. Biggar (1922–36). Champlain’s works are the only written account of New France at the beginning of the 17th century. As a geographer and “artist” (as a factum states), he illustrated his accounts with numerous maps, of which the most important and the last was that of 1632. It includes a list of place names not found on the map as well as unpublished explanations. It presents everything known about North America at that time.

See also: Samuel de Champlain: Timeline ; Exploration ; Exploration: Timeline ; Exploration Literature ; Exploration and Travel Literature in French ; History of Cartography in Canada ; Champlain Sea ; Lake Champlain .

Read More // Samuel de Champlain

- Indigenous Peoples in Canada

- First Nations

- St Lawrence

Further Reading

- David Hackett Fischer, Champlain’s Dream (2009).

- Adrianna Morganelli, Samuel de Champlain: From New France to Cape Cod (2005).

- Josepha Sherman, Samuel de Champlain: Explorer of the Great Lakes Region and Founder of Quebec (2002).

External Links

Champlain: Peacemaker and Explorer Check out the book Champlain: Peacemaker and Explorer at the Indigo website.

Exploring the Explorers: Samuel de Champlain Teacher guide for multidisciplinary student investigations into the life of explorer Samuel de Champlain and his role in Canadian history. From the Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

Samuel de Champlain Follow the 17th century explorations of Samuel de Champlain in the multimedia Virtual Museum of New France website.

The works of Samuel de Champlain See a digitized copy of the book “The works of Samuel de Champlain” from archive.org.

Virtual museum of New France

- Virtual museum of new France

- Introduction

- Colonies and Empires

The Explorers

- Economic Activities

- Useful links

- North America Before New France

- From the Middle Ages to the Age of Discovery

- Founding Sites

- French Colonial Expansion and Franco-Amerindian Alliances

- Other New Frances

- Other Colonial Powers

- Wars and Imperial Rivalries

- Governance and Sites of Power

- Jacques Cartier 1534-1542

Samuel de Champlain 1604-1616

- Étienne Brûlé 1615-1621

- Jean Nicollet 1634

- Jean de Quen 1647

- Médard Chouart Des Groseilliers 1654-1660

- Pierre-Esprit Radisson 1659-1660

- Nicolas Perrot 1665-1689

- René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle 1670-1687

- Charles Albanel 1672

- Jacques Marquette 1673

- Louis Jolliet 1673-1694

- Louis Hennepin 1678-1680

- Daniel Greysolon Dulhut 1678-1679

- Louis-Armand de Lom d’Arce, baron Lahontan 1684-1689

- Pierre de Troyes 1686

- Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville 1686-1702

- Antoine Laumet dit de Lamothe Cadillac 1694-1701

- Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye 1732-1739

- Basque Whalers

- Industrial Development

- Commercial Networks

- Immigration

- Social Groups

- Religious Congregations

- Pays d’en Haut and Louisiana

- Entertainment

- Communications

- Health and Medicine

- Vernacular Architecture in New France

Samuel de Champlain (sometimes called Samuel Champlain in English documents) was born at Brouage, in the Saintonge province of Western France, about 1570. He wrote in 1613 that he acquired an interest “from a very young age in the art of navigation, along with a love of the high seas.” He was not yet twenty when he made his first voyage, to Spain and from there to the West Indies and South America. He visited Porto Rico (now Puerto Rico,) Mexico, Colombia, the Bermudas and Panama. Between 1603 and 1635, he made 12 stays in North America. He was an indefatigable explorer – and an assistant to other explorers – in the quest for an overland route across America to the Pacific, and onwards to the riches of the Orient.

The Mystery of Samuel de Champlain

In the title of his first book, published in 1603, Des Sauvages, ou voyage de Samuel Champlain, de Brouage, fait en la France nouvelle l’an mil six cens trois… [“Concerning the Primitives: Or Travels of Samuel Champlain of Brouage, Made in New France in the Year 1603”], Samuel de Champlain indicated that he was a native of Brouage in the Saintonge region of France. But a fire in the 17th century completely destroyed the town records of Brouage, where the young Champlain was believed to have spent his childhood. Since then, historians have speculated about the birth date of the man often described as the “Father of New France.”

The name “Samuel,” taken from the Old Testament, suggests the possibility that Champlain was born into a Protestant family during a period when France was torn by endless conflicts over religion. However, by the time he undertook his voyages of discovery and exploration to Canada, he had definitely converted to Catholicism. The marriage contract between Samuel de Champlain and Hélène Boullé, dated 1610, shows that he was the son of the then-deceased sea captain, Anthoine de Champlain, and Marguerite Le Roy. On this basis, several historians have deduced that Champlain must have been born around 1570.

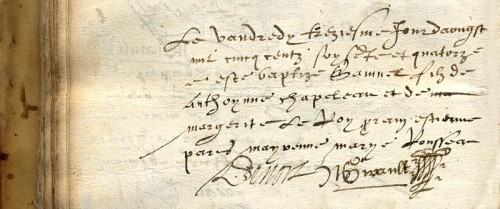

These are the few facts that history reveals, leaving room for all sorts of hypotheses about Champlain’s date of birth. But things were to take a different turn in the spring of 2012 when Jean-Marie Germe, a French genealogist, was examining the archives of the Protestant parish of Saint Yon de La Rochelle. In Champlain’s time, La Rochelle was a neighbouring town and rival of Brouage. What Mr. Germe found there was the baptismal record of Samuel Chapeleau, son of Antoine Chapeleau and Marguerite Le Roy, dated August 13, 1574.

Baptismal certificate of our Samuel de Champlain

Is this the baptismal certificate of the “Father of New France”? Certainly the document is difficult to read; the letters often have to be deciphered as much from their context, as from their appearance. Moreover, in that era the rules of spelling were flexible, to say the least. The different spellings used for the family name of the child and his father can be explained by the fact these names had perhaps previously been written down only rarely. A standard spelling had possibly not yet been adopted.

What are the chances of finding another baptismal certificate dating from this era where the names are identical to those we find in other historical documents? The chances are in fact very small indeed. However, even though the family names of Chapeleau and Champlain are similar, this small difference — understandable as it may be — cautions us not to jump to conclusions. Although the probability is slight, it is still possible that this document has nothing to do with our Samuel de Champlain.

If we are indeed looking at the baptismal certificate of our Samuel de Champlain, we can now say for certain that he was born into a Protestant family, most probably during the summer of 1574. But unless there is another discovery to equal the one made by Mr. Germe, a complete mystery will continue to surround Samuel de Champlain’s date and place of birth.

Baptismal certificate of our Samuel de Champlain, detail

“On Friday, the thirteenth day of August, fifteen hundred and seventy-four, Samuel, son of Antoine Chapeleau and of m [word crossed out] Marguerite Le Roy, was baptized. Godfather, Étienne Paris; godmother, Marie Rousseau. Denors N. Girault.”

In the Footsteps of Jacques Cartier

In 1602 or thereabouts, Henry IV of France appointed Champlain as hydrographer royal. Aymar de Chaste, governor of Dieppe in Northern France, had obtained a monopoly of the fur trade and set up a trading post at Tadoussac. He invited Champlain to join an expedition he was sending there. Champlain’s mission was clear; it was to explore the country called New France, examine its waterways and then choose a site for a large trading factory.

Thus Champlain sailed from Honfleur on the fifteenth of March, 1603, and prepared to follow the route that Jacques Cartier had opened up in 1535. He proceeded to explore part of the valley of the Saguenay river and was led to suspect the existence of Hudson Bay. He then sailed up the St. Lawrence as far as Hochelaga (the site of Montreal.) Nothing was to be seen of the Amerindian people and village which Cartier had visited, and Sault St. Louis (the Lachine Rapids) still seemed impassable. However, Champlain learned from his guides that above the rapids there were three great lakes (Erie, Huron and Ontario) to be explored.

Acadia and the Atlantic Coast

After Aymar de Chaste died in France in 1603, Pierre Du Gua de Monts became lieutenant-general of Acadia. In exchange for a ten years exclusive trading patent, de Monts undertook to settle sixty homesteaders a year in that part of New France. From 1604 to 1607, the search went on for a suitable permanent site for them. It led to the establishment of a short-lived settlement at Port Royal (Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia.)

While the settlers were tilling, building, hunting and fishing, Champlain carried on with his appointed task of investigating the coastline and looking for safe harbours.

The three years stay in Acadia allowed him plenty of time for exploration, description and map-making. He journeyed almost 1,500 kilometres along the Atlantic coast from Maine as far as southernmost Cape Cod.

From Quebec to Lake Champlain

In 1608, Champlain proposed a return to the valley of the St. Lawrence, specifically to Stadacona, which he called Quebec. In his opinion, nowhere else was so suitable for the fur trade and as a starting point from which to search for the elusive route to China. During this third voyage he learned of the existence of Lac Saint Jean (Lake St. John), and on the third of July, 1608, he founded what was to become Quebec City. He immediately set about building his Habitation (residence) there.

Champlain also explored the Iroquois River (now called the Richelieu), which led him on the fourteenth of July, 1609, to the lake which would later bear his name. Like the traders who had preceded him, he sided with the Hurons, Algonquins and Montaignais against the Iroquois. This intervention in local politics was ultimately responsible for the warlike relations that were to pit the Iroquois against the French for generations.

From the Ottawa Valley to Lake Huron

In 1611, Champlain returned to the area of the Hochelaga islands. He found an ideal harbour, and facing it he built the Place Royale (royal square), around which the town would later develop from 1642 onwards.

Even more important, he succeeded in penetrating beyond the Lachine Rapids, becoming the first European (apart from Étienne Brûlé) to start exploring the St. Lawrence and its tributaries as a route towards the interior of the continent. Champlain was so convinced that it was the route to the Orient that in 1612 he obtained a commission to “search for a free passage by which to reach the country called China.” Like most of the explorers who followed after him, he could not carry out his mission without the support of the Amerindian population.

The following year Champlain was induced to make a voyage up the Ottawa River in the course of which he reached Allumette Island. It was his initial foray along the route that was to lead him to the heartland of present-day Ontario and eventually to reach Lake Huron on the first of August, 1615.

That was to be Champlain’s last voyage of exploration. In the years that followed, he devoted all his efforts to founding a French colony in the St. Lawrence valley. The keystone of his project was the settlement at Quebec.

When it capitulated to the English Kirke brothers in 1629, Champlain returned to France, where he lobbied incessantly for the cause of New France. He finally returned to Canada on the twenty-second of May, 1633. At the time of his death at Quebec on the twenty-fifth of December, 1635, there were one hundred and fifty French men and women living in the colony.

Français

Mapping Champlain's journeys

Samuel de Champlain spent much time writing descriptions of the territory and peoples he encountered in the place that is now North America. He was also a maker of maps. His maps and writings provide us with an understanding of where he travelled and how he interpreted the places he visited and people he met.

“Although today Champlain is best known to the general public for having placed on a permanent footing the French presence in North America, individuals interested in the history of cartography and of exploration hold him in high regard for the exceptional quality of his maps and plans.” – Conrad E. Heidenreich and Edward H. Dahl, “Samuel de Champlain’s Cartography, 1603-32,” 2004.

Modern cartographers have drawn upon Champlain’s maps and descriptions to produce their own representations of his travels and explorations in North America. Their maps help place Champlain’s journeys in the context of a more current understanding of the geography of North America.

The maps shown here provide a more recent interpretation of Champlain’s journeys and the territories and trade routes of the aboriginal nations he encountered.

As our understanding of Champlain’s journeys in North America and his relationship with its Aboriginal Peoples continues to evolve, so do the writings and maps produced about him and his travels. These written and cartographic contributions to the story of Champlain are in many ways products of the time and place in which they were produced. Changes in technology also lead to new possibilities for cartographic interpretations of his travels, explorations and interactions.

A recent mapping project undertaken by cartographers at the Canadian-American Center, University of Maine, resulted in a new explanatory map that illustrates the travels and explorations of Samuel de Champlain in Canada between 1603 and 1616. Through its creative inclusion of stories, emotions and Aboriginal voices and place names, this map broadens our understanding of Champlain’s journeys in North America and opens up new possibilities for cartographic interpretation of this aspect of Canadian history.

- Mission Statement

- Collections

- Imaging Services

- Student Employment

- Make Appointment

- Group Tours

- K-12 Field Trips

- Summer Camp

- Book a K-12 Visit or Kit

- Field Trips

- Classroom Activity Kits

- Professional Development

- Downloadables

- Mapmaking Contest

- News & Events

- Search The Collection

- Browse Maps

- Gallery Exhibits

- Map Commentaries

- Digital Exhibits

- Reference Books

- Digital Commons

- Ask a Librarian

- EXHIBIT SECTION |

II. Samuel de Champlain and New France

- Terms of Use |

- Privacy Policy |

The French Crown paid little attention to the St. Lawrence and northeast North America after the failure of Jacques Cartier’s settlement at Kébec/Québec (1535-41). The fishermen and fur trappers continued on their annual migrations to the St. Lawrence without government interference. This changed soon after 1600, when Henri IV sought once again to encourage permanent French settlement in the region. A small fleet was sent out in 1604-07 under the sieur de Mons to establish this colony somewhere in Acadia. Verrazano had originally called the area of present-day New Jersey ‘Acadia,’ but the area had been steadily pushed eastwards across the map, until it covered the region from Nova Scotia to Maine. De Mons fixed on the estuary of the St. Croix River for his initial base before founding Port Royal in Nova Scotia. Accompanying the fleet was an experienced mariner and soldier, Samuel de Champlain, who had already sailed to New France and back in 1603. Champlain was now given the task of charting the coast of Acadia in detail, from Cape Cod to the Bay of Fundy. In addition to mapping the general course and character of the coast, Champlain made detailed maps of potentially important estuaries and bays. Furthermore, Champlain extended his examination and recording of the landscape to encompass the indigenous vegetation, the Native peoples, and their activities. The results were the first printed large-scale maps and the first detailed ethnographic images produced for the New England region (9-14). Champlain published his journals and maps from his 1604-07 voyages in conjunction with those from his 1608-13 explorations and military campaigns along the St. Lawrence. The general map accompanying Les Voyages de Sieur de Champlain (Paris, 1613) defined the basic geography of the region for much of the seventeenth century (15). Champlain did make some modifications to his maps as he gathered more information on his subsequent voyages of 1615-16 and 1618 (17-20), and the changes were picked up by other mapmakers in Paris. The corpus of Champlain’s maps which has been gathered together here thus constitutes a rich and varied record of the territorial development of New France.

FIGVRE DE LA TERRE NEVVE ...

Lescarbot had taken part in de Mons' expedition to Acadia in 1603-07. He wrote the first history of the expedition and its settlements, publishing it in Paris in 1609. For his map, Lescarbot used Champlain's manuscript chart of his explorations (now in the Library of Congress); for the area of New England, his map is therefore very similar to Champlains (15). For the St. Lawrence, however, he had to rely on much older information.

map/7359.0072

MARC LESCARBOT (French, 1590-1630) FIGVRE DE LA TERRE NEVVE ... In: Histoire de la Nouvelle-France ..., 2nd ed. (Paris: Jean Millot, 1612) Woodcut, 17.6 x 42.5 cm Osher Collection

SAMUEL DE CHAMPLAIN

These are the four large-scale maps produced by Champlain's detailed surveys of Maine river estuaries (9-12). The two St. Croix plans were produced during the winter of 1604-05, as de Mons' expedition wintered on the island. The highly accurate maps of the mouths of the Kennebeck and Saco rivers, complete with soundings and sand bars, were made in July 1605. Two more of Champlain's large-scale estuary maps depict sites in Massachusetts, including an attack on a later French expedition to the Cape Cod area (13, 14). Unlike Champlain's charts and regional maps, which were constructed rather abstractly from the distances and directions of his voyages, these large-scale maps were made from Champlain's direct observation and sketching of the landscape itself. The results were highly accurate for such small areas.

Isle de sainte Croix Engraving, 15.1 x 25.4 cm (image) From: Les Voyages de Sieur de Champlain ... (Paris, 1613) Osher Collection

Habitasion de l ile stte croix Engraving, 11.4 x 15.2 cm (image) Osher Collection

Qui ni be quy [Mouth of the Kennebec River]

img/flat/car37.jpg

Qui ni be quy [Mouth of the Kennebec River] Engraving, 11.1 x 16.1 cm (image) Browder Collection

Chouacoit [Saco Bay]

img/flat/car38.jpg

Chouacoit [Saco Bay] Engraving, 11.2 x 15.7 cm (image) Browder Collection

[Attack at Chatham, Mass., October 15, 1606]

img/flat/car39.jpg

[Attack at Chatham, Mass., October 15, 1606] Engraving, 14.8 x 23.7 cm Browder Collection

Malle Barre [Nauset, Mass.]

img/flat/car40.jpg

Malle Barre [Nauset, Mass.] Engraving, 14.9 x 24.2 cm (image) Browder Collection

CARTE GEOGRAPHIQUE DE LA NOVVELLE FRANSE . . . faict len 1612

Champlain merged his general information regarding the New England coast with his later explorations of the St. Lawrence valley (to 1612). The result is his large and ornate general map of New France (15). Even on this map, however, Champlain refers to the manner in which he himself had seen this entire region by including the ethnographic and botanical drawings (15).

map/4072.0001

SAMUEL DE CHAMPLAIN (French, 1567-1635) From: Les Voyages de Sieur de Champlain ... (Paris, 1613) CARTE GEOGRAPHIQUE DE LA NOVVELLE FRANSE . . . faict len 1612 Facsimile of hand-colored engraving, 43.0 x 77.6 cm Smith Collection

[Various Ethnographic Images]

Champlain had applied to New France the European habit of examining Native peoples in the same way as they examined landscapes. He was not alone in this regard. A century later, the tradition was still strong when the baron de Lahontan sketched these ethnographic images of various ceremonies and practices among the Abanaki.

img/flat/car11.jpg

LOUIS DE LAHONTAN (French, 1666-1715) [Various Ethnographic Images] From: Nouveaux voyages ... dans l'Amerique septentrionale ... (Paris, 1703, 2 vols.) Facsimiles of wood-cuts, each 13.4 x 8.5 cm Smith Collection

Carte de la nouuelle france ...

After constructing his map of 1612 (15), Champlain returned to New France several times and acquired yet further information. The expansion of the French fur trade led to increasing interaction with, and the gathering of more geographical information from, the Hurons of the St. Lawrence valley. Champlain accordingly updated his map and expanded its geographical scope in this map made to accompany his general history of New France.

img/flat/car12.jpg

SAMUEL DE CHAMPLAIN (French, 1567-1635) Carte de la nouuelle france ... In: Les Voyages de la Novvelle France occidentale ... (Paris, 1632) Engraving, 52.2 x ca.96.5 Osher Collection

DESCRIPTION DE LA NOVVELLE FRANCE

JBoisseau took Champlain's large map of 1632 (17) and reduced it in size to make a more commercially viable product. He was, after all, a commercial cartographer and not a navigator. Although eleven years had passed since Champlain's original map had been published, Boiseau did not try to add any new details or place-names from any of the English or other French voyages. Instead, as has almost always been the case in commercial mapmaking, he simply copied his source directly. One benefit of Boisseau's reduction of Champlain's map is that it is now easier to contrast the configuration of New England on Champlain's original (15b) and later (18a) maps.

JEAN BOISSEAU (French, fl. 1637-1658) DESCRIPTION DE LA NOVVELLE FRANCE Paris: Jean Boisseau, 1643 Engraving, hand colored, 35.0 x 55.0 cm Osher Collection

[La Nouvelle France] faict par le Sr. de Champlain. 1616

img/flat/car14.jpg

SAMUEL DE CHAMPLAIN (French, 1567-1635) [La Nouvelle France] faict par le Sr. de Champlain. 1616 Paris, ca.1619 Facsimile of an engraving, 34.5 x 53.7 cm Smith Collection

LE CANADA faict par le Sr de Champlain ...

Champlain's cartographic record is made all the more complex by his construction in 1616 of a new regional map of New France, with the addition of his explorations since 1612 (19). The image is clearly similar to what Champlain eventually published in 1632 (17), but is much smaller in scale. The only copy known of this map is now in the John Carter Brown Library, R.I. It is clearly an unfinished printer's proof copy. Despite the date on the map (1616), the evidence of the paper dates this impression of the map to about 1653. That is, Champlain had the new map engraved, but abandoned the project before completion. The copper plate survived, however, and was acquired by Pierre Du Val. Du Val finished the map and published it in 1653; on display here is a later state, from 1677 (20).

PIERRE DU VAL (French, 1618-1683) LE CANADA faict par le Sr de Champlain ... Paris, 1677 Engraving, hand colored, 34.8 x 54.3 cm Smith Collection

- Basic Search

- Advanced Search

- Imagery Search

- Content Search

- Site Search

A portion of the holdings in these collections have been optimized to allow searching for elements within a given map, such as sea monsters, decorative borders, cartouche, or other imagery. This search screen will allow you to search these elements, but remember it is only searching a fraction of the collections.

- MURDER IN THE METRO

- ASSASSINATION IN VICHY

- SAMUEL DE CHAMPLAIN

- THE NEW WORLD MERCHANTS OF ROUEN

- HENRY IV AND THE TOWNS

- GAYLE K. BRUNELLE

- ANNETTE FINLEY-CROSWHITE

- EVENTS & ARTIFACTS

- RESOURCE PAGE

Samuel de Champlain

An ideal resource for students complete with documents.

About the book

Samuel de Champlain — explorer, cartographer, administrator and diplomat to the Native American peoples he encountered — made twelve voyages to North America between 1603 and 1633. He authored four accounts of his explorations and observations, each published in his own day and lavishly illustrated with maps and engravings. Champlain’s Works became increasingly popular after his death and ultimately shaped the founding narratives of the colonization of northeastern North America and the creation of New France. In this volume, Gayle K. Brunelle offers a thorough and balanced examination of Champlain’s life and career, and invites students to consider how, through his explorations, his writings, and his remarkable maps, Champlain shaped our understanding of early North American history. Document headnotes, maps and illustrations, a chronology of events, questions to consider, a selected bibliography, and an index are provided to enrich student understanding.

What are people saying?

Where to buy.

Take a journey with us into the past.

Co-Authored works

- Murder in the Metro

- Assasination in Vichy

Individual works

- Samuel De Champlain

- The new world merchants of Rouen

- Henry IV and the towns

- Annette Finley-Croswhite

- Gayle K. Brunelle

Events & Artifacts

Samuel de Champlain

(1574 – 1635), "The Father of New France", was a French explorer, navigator, cartographer, soldier, geographer, ethnologist, diplomat, and chronicler. He founded Quebec City on July 3, 1608 and is important because he made the first accurate map of the coast.

- Amerigo Vespucci

- Ferdinand Magellan

- Article The First

- America’s Four Republics

- No Taxation Without PROPER Representation

Sunday, March 24, 2013

Among the curiosities of -newly-discovered America was the Indian canoe. Its slender and elegant form, its rapid movement, its capacity to bear burdens and resist the rage of the billows and torrents, excited no small degree of admiration for the skill by which it was constructed.

but for the mistake of Champlain, and the unwise treatment of the Five Nations that followed, the government of the continent would have fallen to the French rather than to the English.

The whole confederacy, except a little more than half of the Oneidas, hung like the scythe of death upon the rear of our settlements, and their deeds are inscribed with the scalping-knife and the tomahawk in characters of blood on the fields of Wyoming and Cherry Valley, and on the banks of the Mohawk.

"but for a headwind when off Cape Cod, sailing southward in 1605, Champlain might have reached the Hudson, and instead of planting Port Royal in Nova Scotia, he might have established its foundations on Manhattan Island, and that this would have made the greatest city in America a French city."

"He was wise, modest, and judicious in council; prompt, vigorous, and practical in administration; simple and frugal in his mode of life; persistent and unyielding in the execution of his plans; brave and valient in danger; unselfish, honest, and conscientious in the discharge of duty."

OTTAWA REWIND

Join me as we wind back the time in ottawa., tracking champlain: plotting the explorer’s epic journey on the 400th anniversary.

400 years ago this week one of the world’s most renowned explorers set out on an epic journey…This autumn marks the Quadricentennial of Samuel de Champlain’s adventurous voyage through Central-Eastern Ontario along its many waterways and through its forests. With a team of Huron warriors on a mission to defeat the Iroquois in what is now Upper New York state, Champlain walked and paddled through our own backyard. Using current mapping technology and Champlain’s very own detailed journal entries we can plot the famous explorer’s 400 year old expedition…

In 1615 on another exploration of the new frontier, Champlain made his way down the St. Lawrence River and was greeted by a large contingent from the Huron and Algonquin nations. The explorer met these aboriginal nations before on one of his earlier journeys, and now they asked Champlain to help them defeat the Onondaga and Oneida nations to the south in what is now Upper New York state. Champlain knew these opposition tribes to the south posed a great threat to the French fur trade routes along the upper St. Lawrence and Ottawa rivers. He realized that by allying with the Hurons and Algonquins, they may be able to defeat this threat to the south and clear the way for French trade on Lake Ontario, Ottawa River and St. Lawrence River.

In an agreement to help his allies, Champlain returned to Quebec to plan an attack and make the necessary equipment preparations for the journey that would take him and his native companions deep into enemy territory. That summer of 1615 his French contingent traveled by a flotilla of canoes along the Ottawa River to Morrison Island then along the Mattawa River and through Lake Nipissing. Working to promote strong alliances with the French between the aboriginal people he met en route, Champlain and company made their way along the French River into Lake Huron across Georgian Bay to a site near what is now Penetanguishene. He arrived in “Huronia” in August of 1615 and began to sit down with members of the Huron nation to plan their attack of the Iroquois at their large fortification across Lake Ontario in New York State. With the necessary preparations having been made, Champalin embarked in September 1615 with a massive war party outfitted with canoes laden with tribal warriors, armed Frenchmen, and the supplies needed to make the bold journey to defeat the powerful Iroquois to the south.

Thankfully for history’s sake, Champlain made a very detailed journal of this adventure, and in 1907, “Champlain’s Voyages et Descouvertures” was translated and printed by the American Historical Association into a book titled “VOYAGES and Explorations of Samuel De Champlain narrated by himself”

A translated copy of Champlain’s journal used to plot out his 1615 adventure.

Obtaining a scanned version of a Canadian 1911 version of the journal and isolating the journey Champlain made through Central-Eastern Ontario in 1615 we can re-create the trip. His entries are detailed, and the translation helps pinpoint exact locations that I was able to match to current existing landmarks. Having grown up in the same area in my teenage years and having sailed some of the exact same waters traversed by Champlain, I believe I was able to map out this epic journey as it happened 400 years ago.

MEASURING CHAMPLAIN’S DISTANCES

Before we begin we must first start deciphering this 400 year old adventure with an analysis of the original journal and how it translates into present day terms. The first mention Champlain makes about the start his journey is on Page 76 where he mentions they gathered two canoes with 12 of the strongest “savages”, continuing his way towards the enemy. Champlain then uses the term “lieue”or “league” to measure distance on his journey. But what is a league, how far is that in today’s modern measurement of distance? This of course is crucial to tracking Champlain properly and is a key element to matching his distances on today’s maps for an accurate plotting of his route.

A conversion of a 1600’s French league to our modern kilometres was necessary to accurately plot his journey.

The “old French league” was a measurement used by the French up until 1674 and was defined as 10,000ft. With Champlain traveling in 1615 and his journal of his exploits being published soon after, this falls into the right unit of measurement for that time. 10,000 feet converts into a modern metric measurement of 3.25km. The French League however differed with Champlain depending on what type of surface he was traveling on. A French Land League ranged between 3.25km-4.68km, (an average of 4km). Champlain used a different measure of league at different points of his adventures, on the open sea and St. Lawrence River he used a league that was 4.0-4.5km compared to the approximate 3.4km league he used for inland travel. Because Champlain was traveling over both land and water on this 1615 journey which makes it almost impossible to pinpoint an EXACT measurement of his mentioned league. So I will be using the average of 3.5km=one Champlain league.

THE JOURNEY

After leaving Huronia on September 1 1615, Champlain travels across Lake Simcoe and entered what is now the Trent-Severn Waterway where his journal mentions travelling south and entering Sturgeon Lake. From Sturgeon lake Champlain mentions:

“From it flows a river that empties into the great lake of the Entouhonorons”

The “Lake of the Entouhonorons” is Lake Ontario. Champlain describes the journey down the Otanabee and Trent rivers which empty into Lake Ontario from Sturgeon Lake as being “about 64 leagues-that is to the entrance to of this lake of the Entouhonorons”

Now we can utilize our measurement of a league (3.5km) which calculates 64leagues x 3.5km=224km. This distance mapped out on a current map where the Trent flows from Sturgeon Lake to Lake Ontario at Trenton is almost a perfect match.

Using a mapping program we are able to track the “64 leagues” or 224Km Champlain mentions it took to go from Sturgeon Lake to where the Trent River empties into Lake Ontario at Trenton.

Our journey begins on at Sturgeon Lake where Champlain passed through in September 400 years ago. (GoogleMaps)

Champlain also mentions passing 5 rapids and smaller lakes along the way. The matches the pre-Trent canal rapids at Bobcaygeon, Buckhorn, Peterborough, and the many other falls and rapids they would have encountered along the Otanabee and Trent rivers.

Otanabee River Champlain and his Huron warriors travelled along. (Google Maps)

Champlain mentions how beautiful the river area is and that it seemed eerily abandoned of people. It is noteworthy to mention that some think Champlain is speaking of Prince Edward County at this point, but the journal and mapping do not make this possible.

Some of the rapids Champlain mentions in his journal on the Trent River.

CHAMPLAIN’S WEAPON

Along the Otanabee and Trent, Champlain watches his native companions hunt with spears and one of them is injured when one of Champlain’s men tries to also hunt with their own weapon, an “arquebus” which is a type of matchlock musket used by Champlain and his French companions. A heavy weapon between 30 and 50 inches in length, Champlain’s arquebus fired 1 ounce lead balls through a straight barrel, capable of felling large game and men. This was Champlain’s weapon of choice on his adventure 400 years ago.

Champlain used an “arquebus” similar to this as his weapon of choice on the adventure.

After Champlain and team empty into Lake Ontario (what Champlain calls Entouhonorons) at Trenton, they entered what is now the Bay Of Quinte and Prince Edward County. Passing along through the Bay Of Quinte past Deseronto, Picton and finally into the main body of Lake Ontario near Adolphustown, Champlain and company head east along the northern shore.

This is where Champlain would have exited from the river into “Lake of the Entouhonorons”, or as we now call it, Trenton on Lake Ontario.(GoogleMaps)

They would have passed Bath, Millhaven, Amherstview and Kingston. It is here that I firmly believe that scholars and the history books are incorrect in their assumption that Champlain cut down into the lake on the eastern end of Prince Edward County towards the Main Duck islands.

Cruising along the Bay of Quinte in the same waters Champlain traversed 400 years ago.

The route I believe Champlain took on his 1615 journey.

Champlain’s actual map he drew of the land he explored drawn in 1632. I marked his route in red.

Another map of Champlain’s with his route marked in red.

The accepted route Champlain supposedly took but I think it is incorrect.

Champlain mentions in the journal:

“we went across at the eastern end, which is the entrance to the great River St. Lawrence at latitude 43 degrees where there are some beautiful and very large islands in this passage”

This description tells me Champlain travelled along the northern shore of Lake Ontrio to Kingston, where the St. Lawrence begins as he mentions. It is here that there are also the “VERY beautiful and LARGE ISLANDS” he mentions would have been Amherst Island, Wolfe Island, Grenadier ISland and Galoo Island. Having sailed these exact waters, I know that this would make the most logical location to traverse Lake Ontario as it is more sheltered than the open lake of the accepted Main Duck Island route.

The gap where I think Champlain went through to go across Lake Ontario.

The “large beautiful islands” Champlain makes note of in his journal as he crossed the eastern end of the lake were lost likely Wolfe Islands, Galoo and Stony Islands to name a few.

Champlain’s native companions would have known this and also being in river canoes, have most likely traversed at the far eastern end of the lake around the shelter of the islands he mentions instead of going across the open waters of the lake with its treacherous autumn winds. Also, the latitude of 43 degrees he mentions puts Champlain in the Wolfe Island/Grenadier/Galoo Island area.

Using that area as his crossing point, the journal then mentions he traversed across “about 14 leagues to get to the other side of the lake in a southerly direction” . The distance of 14 leagues x 3.5km gives us a distance of about 50km they travelled across the lake. It is here, in late September 1615 that Champlain hit the shores of present New York state. The following journal details and description allow us to now pinpoint where this was, which I believe to be El Dorado Beach, NY.

Where Champlain likely landed in New York state in late September 1615.

ENTERING NEW YORK STATE

Champlain explains that once they reached the shore of the enemy and hid their canoes in the woods,

“we went about 4 leagues by land along a sandy beach , where I observed a very agreeable and beautiful country crossed by several little brooks and two small rivers which empty into this lake; and a great many lands and meadows..”

Champlain’s description and clues reveal:

- a sandy beach

- several little brooks

- two small rivers

These clues all point to Champlain landing at what is now EL DORADO BEACH Preserve, just southwest of what is now Henderson, NY. NOT Hernderson Harbour as others believe. I think El Dorado Beach is where Champlain and his warriors first landed because it is a beach area that stretches south for exactly 14km that he mentions walking along (4 leagues x 3.5km=14km).

Aerial view of Champlain’s landing point.

The beach Champlain walked along with his invading war party.

The two small rivers he mentions would be Sandy Creek and the Salmon River. The “several little brooks” would be the various creeks that dissipate in from the beach. Next Champlain mentions in his journal “a great many ponds and meadows where there were an unlimited amount of game”.

The marshes Champlain mentions with lots of game.

These ponds would likely be the Lakeview Pond, North Sandy Pond and many other ponds that lie behind the beach, now called Southwick Beach in New York state that he walked south along around Oct.1 1615. I am not sure if there has ever been a proper archeological investigation into this 14km stretch of beach area where Champlain landed and traversed, but I’m sure a number of artefacts lie buried in the sand from this 400 year old expedition, waiting to be discovered.

Beach Champlain walked along.

It is from this beach in NY state that Champlain continued down into Upper New York state for four days on foot through Oswego and Onondaga Counties to the Oneida River.

After walking along the coast of Lake Ontario, Champlain enters the Oswego River and follows its shores inland. (Google Maps)

Champlain followed the river inland to Lake Oneida that he mentions in his journal. (Google Maps)

The inland journey Champlain would have taken.

On October 9 Champlain encountered enemy Iroqouis while on scouting mission that they took prisoner. On October 10 1615, Champlain and his band of native warriors reached their destination: the immense palisaded fortress of the Iroquois.

Champlain’s own sketch of the Iroquois fortress he attacked on Oct.10 1615. Note the two rivers either side and Lake Onondaga at top.

This was an Iroquois stronghold whose exact location has been the subject of much controversy due to Champlain’s scant details on getting there. Other than simply saying it was located “between two streams” there are few details that help locate where this fort would have been. In his 2009 book “Champlain’s Dream” author David Fischer speculates historians have been incorrect in their assumption the Iroquois fortress was in Fenner, NY within Madison County. Fischer postulates that the fort was probably in between two streams at the south end of Lake Onandaga in Syracuse NY where the present day Carousel Shopping Mall resides.

Where the fortress was it is now a shopping mall. Note two rivers either side.

Streetview of where the fort likely stood. Now a Syracuse shopping mall.