- Free general admission

1932–33: English cricket team on ‘bodyline’ Ashes tour

The 1932–33 Ashes series is the most controversial in the history of Australian–English Test cricket.

The English team, desperate to contain Australian batsman Don Bradman and win back the Ashes, adopted a controversial strategy. Technically known as ‘fast leg theory’, it was better known as ‘bodyline’.

It came close to turning a summer of cricket into a diplomatic row.

Bill Woodfull, Australian captain, 1933:

There are two teams out there; one is trying to play cricket and the other is not.

Third Test, January 1933, Adelaide Oval. State Library of South Australia B8660

Bradman problem

The 1932–33 Ashes series is the most controversial in the history of Australian-English Test cricket. The English team, desperate to contain Australian batsman Don Bradman and win back the Ashes, adopted a controversial strategy. Technically known as ‘fast leg theory’, it was better known as ‘Bodyline’.

The Great Depression was weighing heavily on Australians. Unemployment was rising and austerity measures, recommended to the Australian Government by British economists, were widely resented.

During Australia’s tour of England in 1930, the young Don Bradman dominated the English bowlers. During the Test series, Bradman scored 974 runs (an average of 139.14) including one single century, two doubles and a triple (334), which broke the world Test batting record. This caused significant disquiet for the English cricketing community but elation in Australia where Bradman returned a hero.

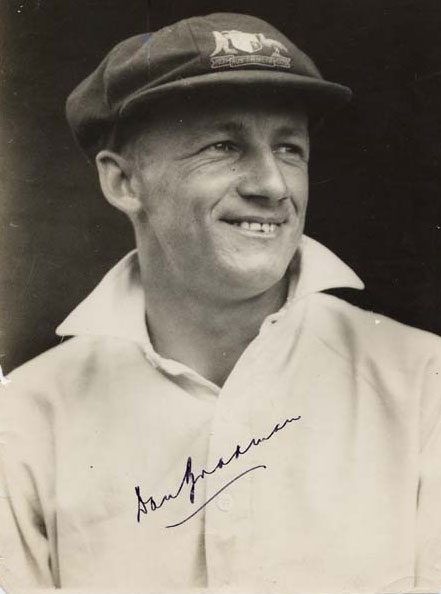

Portrait of Donald Bradman. Bradman Museum Trust Collection, Bowral

Douglas Jardine

In preparing for their 1932 tour to Australia, England sought a way to stifle Bradman’s scoring. Their captain, Douglas Jardine, developed an approach in which the ball was bowled fast and short, rising up to the batsman's body while fielders hovered close to the leg side.

The strategy was intended to intimidate the batsman, stifle the swing of his bat and force him to play defensively. But it also posed a genuine physical threat.

The relationship between Jardine and Australian cricket fans was already tense. During the 1928–29 tour to Australia he was perceived as supercilious and rude. His air of upper-class superiority rankled with the Australian crowds.

As captain for the 1932–33 series, Jardine made no efforts to remedy the situation, was uncooperative in press interviews and didn’t provide team details before matches. While Jardine’s character exacerbated the situation, his tactics had the backing of the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC).

The Test series began in Sydney with England winning the match. Bradman was absent due to illness. Australia levelled the score in Melbourne. Then during the third Test in Adelaide, the English captain turned to Bodyline tactics.

The already hostile crowd was furious and when one delivery struck Australian captain Bill Woodfull just above the heart it was feared a riot would start. Tempers flared on the field and in the stands, and while Woodfull maintained a diplomatic stance in public, in private he too was furious.

Angry words

A key aspect of Australian frustration was that the English tactics seemed to go against all that was valued in cricket: fair play, ethical conduct and a shared cultural understanding of behaviour. In response to the danger faced by the players, the Australian Board of Control for International Cricket sent a tersely worded telegram to the MCC on 18 January 1933:

Body-line bowling has assumed such proportions as to menace the best interests of the game, making protection of the body by the batsmen the main consideration. This is causing intensely bitter feeling between the players as well as injury. In our opinion it is unsportsmanlike. Unless stopped at once it is likely to upset the friendly relations existing between Australia and England.

The English administrators did not appreciate their players being accused of unsportsmanlike conduct. Not having witnessed the barrage of body blows, they felt that the Australian side was making excuses. The MCC responded sternly on 23 January:

We, Marylebone Cricket Club, deplore your cable. We deprecate your opinion that there has been unsportsmanlike play… We hope the situation is not now as serious as your cable would seem to indicate, but if it is such as to jeopardize the good relations between English and Australian cricketers and you consider it desirable to cancel remainder of programme we would consent, but with great reluctance.

For a while it seemed that cricket would strain diplomatic relations between Australia and England. After intervention from the Australian Prime Minister Joseph Lyons, the Australian Board of Control withdrew its charge of unsportsmanlike behaviour and the final tests were played. England won the series 4–1 and reclaimed the Ashes.

The impact of England’s bodyline tactics extended beyond the cricket pitch. Struggling with ongoing hardship during the Depression, Australians saw the aggressive tactics of the English team as representative of England’s wider attitude to the country.

While riots and diplomatic rows were averted, the series challenged not only a shared understanding of cricket but tested Australia’s changing relationship with England and empire.

In our collection

Digital Classroom

Explore free online learning resources on Australia's Defining Moments Digital Classroom.

- science and technology

Explore Defining Moments

You may also like

Information about the Bodyline Series, State Library of NSW

David Frith, Bodyline Autopsy: The Full Story of the Most Sensational Test Cricket Series: Australia v England 1932–33, ABC Books for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Sydney, 2002.

Ric Sissons and Brian Stoddart, Cricket and Empire: The 1932–33 Bodyline Tour of Australia, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1984.

The National Museum of Australia acknowledges First Australians and recognises their continuous connection to Country, community and culture.

This website contains names, images and voices of deceased Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

- India v England – 4th Test at Ranchi Feb 23rd to 27th – Live Stream

- India’s Bench Strength Display Alleviates Transition Worries

- Bumrah Set for Rest, Fit-again Rahul Poised to Return for Ranchi Test

- Shreyas Iyer Excluded as India Finalises Squad for Remaining England Tests

- Exclusion of Cameron Bancroft Not Tied to 2018 Ball-Tampering Scandal, Emphasises Cricket Selector

The Bodyline Series : The Ashes 1932/1933

- From The Vault: Tests

The MCC tour of Australia and New Zealand in 1932/33 was one of the finest – and one of the most controversial – Test series ever played and was nicknamed ‘The Bodyline Series.’ When Wally Hammond and Bob Wyatt put on 125 for the third wicket to gain victory for England by eight wickets in Sydney, it capped a remarkable winter for the tourists and sealed a crushing 4-1 series victory. Still to this day it remains one of English cricket’s greatest overseas triumphs. Rarely before and likewise, rarely since has pure theory been so completely matched to the needs of applied cricket and it is this reason why Douglas Robert Jardine is remembered as arguably the finest captain to ever lead for England and why paceman, Harold Larwood, is maybe still the greatest fast-bowler to take on the Australians. No other series caused such controversy and although Jardine may no longer be the most hated man in Australia, few Antipodeans even these days afford him the benefit of the doubt. The great Englishman would have it no other way, but like many great Englishmen, he was born outside of England, in Scotland. The term ‘Bodyline’ refers to the less threatening and so much less venal sounding term, ‘fast leg-theory’. Fast leg-theory was what it was and leg-theory was hardly a recent innovation in those times. It had existed for a quarter of a century before Jardine ever unleashed Larwood upon an unsuspecting and easily-offended Australian public. The difference was accuracy . Inaccurate Bodyline bowling may have been able to frighten a batsman but, provided he kept his wits about him and, more importantly, his eye on the ball, it would not endanger his wicket (albeit sometimes his life). Larwood, fairly unique amongst his peers, had that accuracy. Despite the fact that 16 of his 33 dismissals during the series were bowled, his ability to get the ball to rise from back of a length on the largely unresponsive Australian pitches of that era was a truly remarkable achievement. Amongst all the controversy of supposedly targeting the batsman’s body in preference to the stumps, it is sometimes forgotten that Australia posted reasonable, although not massive, first innings scores. They batted first, four out of five times and made scores of 360, 228, 222, 340 and 435 which were countered by English totals of 524, 169, 341, 356 and 454. In the first of these, Bradman was absent and Australia won the second Test largely due to a century from the Don and 10 wickets from O’Reilly. In four of the five tests England enjoyed a half-time advantage but only twice was this a large supremacy. It was the second innings what won it: Australia never passed 200. One of the reasons this turned out to be an epic series, and a sometimes forgotten fact in all of this, is that Australia fielded an excellent side themselves. A lack of fast-bowling was their only real weakness. Nevertheless Australia’s courageous skipper could, at various times, call on the talents of Ponsford, McCabe, Kippax, Richardson, O’Reilly and Grimmet. And then there was Bradman. Ordinarily his presence ensured that, effectively, Australia pitted 12 players against the opposition’s 11. Jardine’s challenge, and his achievement, was to even the odds. Reduce Bradman to mere mortal status and the game would revert to the traditional 11 vs 11. Of the many people who attempted to solve the Bradman Problem, Jardine was the only man to do so, and only by a narrow margin as well. One of Bradman’s more mind-boggling statistics was that while he made 29 centuries he was only dismissed 13 times between 50 and 100. Breaking that down it meant that during his career, once he made 50 he was twice as likely to go on and score a century, a statistic never matched by anyone else. The scale of the challenge facing Jardine was enormous. In 1930 Bradman had decimated England scoring 974 runs at an average of 139. He played seven innings that summer and reached at least a century in four of them. The following summer he took the South Africans for another 806 runs at an average of 201, with four centuries in five innings. Something new and different was needed to nullify Bradman. And Jardine had to find that something new for a series to be played on dull Australian pitches and in conditions unlikely to prove conducive to swing bowling. The prevailing conditions – including a still-batsman-friendly LBW law – dictated English tactics almost as much as did the need to counter Bradman. The ball would be softening after no more than 15 overs, allowing the Australian batsmen the freedom of the off-side would have been an invitation to make hay. Bodyline was a means of rebalancing the game, chipping away at the in-built advantage batsmen enjoyed at the time and (especially) in those Australian conditions. During the matches, Jardine would just nod his head and the team would swarm to the leg side to take up their positions. The pot boiled over in the third Test at Adelaide, aptly termed, the most unpleasant Test ever played. The series stood at one all at this point and a win for either team would have put one hand on the urn. The main controversy arose when Australian batsmen were felled by English bouncers. Often though it is forgotten that when Larwood struck Woodfull a hefty blow above the heart, he was employing an orthodox field. The same is true when Bert Oldfield ducked into a Larwood bouncer and was struck on the head. Oldfield did exonerate Larwood by admitting it was his own fault. These were the moments that won the Ashes. As Woodfull bounded in agony, clutching his chest, the silence was broken by the English skipper. “Well bowled, Harold” Jardine said in a voice loud enough for all to hear and with a nod and a clap of his hands he signalled his fielders to move to their leg-theory positions for the very next ball. It was, amidst the shouting and barracking, a masterstroke of cold-blooded captaincy and still, deservedly, perhaps the most famous change-of-field in the history of the great game. Woodfull was furious over all of this, and when Plum Warner made his way to the Australian dressing-room to inquire about the extent of the injuries, the England manager was met with this phrase:- “I don’t want to see you, Mr Warner. There are two teams out there; one is trying to play cricket and the other is not. The matter is in your hands, Mr Warner, and I have nothing further to say to you. Good afternoon.” There is often something relative about cricketing success. Bradman had his least successful season that winter and in eight innings he made just a single century and dismissed three times between 50 and 100. But he averaged 56 for the series, one more than Hammond who averaged 55. But reducing Bradman to Hammond’s level of performance constituted a great victory for England. cont below…….

Bodyline Series Video Collection

All eight episodes in the TV drama from 1984 following the Ashes series of 1932/33

Bodyline Series

cont from above….

The Don adapted his method. Just as England attacked him so he attacked England. He scored at a rate of 74 runs per 100 balls that Australian summer. Both sides gambled. England looked to make life difficult for Bradman with the Don betting that he could score enough runs quickly enough to make up for the fact that, considering the bowling and tactics used, sooner or later a ball would arrive that had even his number on it. He was half-right and he half-succeeded . That, in its way, is one of the greatest measurements of his unparalleled genius. But Bodyline was not quite the total all-out war it is sometimes imagined to be. In the first instance, even Larwood did not always bowl to a leg-side trap. Secondly, neither Bill Voce nor, in the one test he played, Bill Bowes, proved able to match Larwood’s accuracy or pace for that matter. Thirdly, Gubby Allen refused to bowl Bodyline. And fourthly, Hedley Verity did not take his 11 wickets with Bodyline either. In short, Bodyline was a tactic used relatively sparingly. Perhaps no more than 25% of the overs England delivered that series were bowled to Bodyline fields. Of course it is all relative, and it all looks very different in hindsight and there is little reason to suggest that Bodyline targetted the batsmen in 1932-33 any more than Lillee and Thomson did in the early 1970s or than the great West Indian fast bowlers did later than decade and in the 1980s. Perhaps not every captain should be as ruthless as Jardine, but he was a great captain who completed his task of taming Bradman which required extraordinary measures. Jardine and Larwood perfected those measures. The establishment, however, never forgave Larwood and Jardine for their success. Shamefully, Lords bowed down to Australian suggestions that neither Jardine nor, especially, Larwood should face the Australian tourists on their 1934 tour of England. The “crisis” in Anglo-Australian relations was almost entirely of the Australians’ making. Jardine was removed from the captaincy before the Australians arrived in 1934 and Larwood never played for England after Bodyline. And such is history, in 1934 Donald Bradman scored 759 runs at an average of 94.75 and England lost the Ashes they so dearly won in 1932-33. Despite English cricket disowning the two men, it is good to be reminded that Douglas Jardine never deserted his greatest ally. The story of the present DRJ gave HL is well-known. It was an ashtray engraved with the inscription: “To Harold for the Ashes — 1932-33 — From a grateful Skipper.” Less well-known is the telegram Jardine sent Larwood upon the latter’s emigration to, of all countries, Australia. Larwood gave a sad and lonely farewell to England with no send-off apart from one exception. As the great fast-bowler boarded the boat to Australia at Liverpool he received a telegram. “Bon voyage,” it read. “Take care of yourself. Good luck always. Skipper”. Such is the price of success and so there remains something chilling about Bodyline and the manner in which it is recalled but the game would be poorer had neither Douglas Jardine nor Harold Larwood ever existed. We should remember that.

Article curated from The Spectator

Similar Articles

Classic Cricket Highlights : England v West Indies 2nd Test at Lords 1984 : Greenidge’s Onslaught

Classic Cricket Highlights : England v New Zealand 3rd Test at Old Trafford 1994

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Football Home

- Fixtures - Results

- Premier League

- Champions League

- Europa League

- All Competitions

- All leagues

- Snooker Home

- World Championship

- UK Championship

- Major events

- Olympics Home

- Tennis Home

- Calendar - Results

- Australian Open

- Roland-Garros

- Mountain Bike Home

- UCI Track CL Home

- Men's standings

- Women's standings

- Cycling Home

- Race calendar

- Tour de France

- Vuelta a España

- Giro d'Italia

- Dare to Dream

- Alpine Skiing Home

- Athletics Home

- Diamond League

- World Championships

- World Athletics Indoor Championships

- Biathlon Home

- Cross-Country Skiing Home

- Cycling - Track

- Equestrian Home

- Figure Skating Home

- Formula E Home

- Calendar - results

- DP World Tour

- MotoGP Home

- Motorsports Home

- Speedway GP

- Clips and Highlights

- Rugby World Cup predictor

- Premiership

- Champions Cup

- Challenge Cup

- All Leagues

- Ski Jumping Home

- Speedway GP Home

- Superbikes Home

- The Ocean Race Home

- Triathlon Home

- Hours of Le Mans

- Winter Sports Home

On This Day in 1932: England beat Australia in first Ashes Test of ‘bodyline tour’

/dnl.eurosport.com/sd/img/placeholder/eurosport_logo_1x1.png)

Published 06/05/2015 at 14:44 GMT

England’s cricketers beat Australia in the first Test of the 1932 Ashes series on this day – in a tour they won 4-1 after using controversial bodyline bowling tactics.

Image credit: Eurosport

Rashid insists England have 'mindset of champions' ahead of T20 World Cup

23/04/2024 at 21:23

'That's the truth' - Archer to consider retirement from cricket if injury setbacks continue

18/04/2024 at 10:14

Devine's unbeaten century seals consolation New Zealand win in ODI series against England

07/04/2024 at 11:07

New Zealand captain Devine to return from injury for third ODI against England

06/04/2024 at 08:05

The History of the Ashes

Australia and england first met in test match cricket in melbourne in 1877, but the legend of the ashes, the symbolic trophy the two teams play for, only began in 1882..

By Cricket Australia

Ashes Urn Cricket Australia

Australia and England first met in Test match cricket in Melbourne in 1877, but the legend of The Ashes, the symbolic trophy the two teams play for, only began in 1882. It was 1882 when at the Oval in London, Australia won its first test match on English soil, beating its hosts by seven runs in a match that spanned two days in late August. Four days later a mock obituary, lamenting the home side’s loss, appeared in a newspaper, The Sporting Times, written by Reginald Shirley Brooks. It read: “In Affectionate Remembrance of English cricket, which died at The Oval on 29 August 1882. Deeply lamented by a large circle of sorrowing friends and acquaintances RIP. NB – the body will be cremated and the ashes takes to Australia.”

Ivo and The Ashes, Paradie Regained (1883) by Unknown Melbourne Cricket Ground

England’s captain for the return series in Australia in 1882/83, Ivo Bligh (later Lord Darnley), promised to “regain those ashes” and then, during that tour, a group of ladies in the state of Victoria, including Bligh’s future wife Florence Morphy, presented him with a six-inch (150 millimetre) terracotta urn, possibly a perfume bottle, sealed with a cork and believed to contain the ashes of a burned bail. Later in the tour, Mrs Ann Fletcher gave Bligh a velvet bag to keep the urn inside. Bligh subsequently wrote to Mrs Fletcher thanking her for the “pretty little bag” in a letter now held at the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) Museum at Lord’s Cricket Ground in London.

Photograph of the Ashes urn with explanatory text, c1930 Melbourne Cricket Club

Lord Darnley died in 1927 and his widow presented the urn to the MCC. It was first displayed in the Long Room before it was moved to the Museum in 1953. The urn has twice left Lord’s to be taken to Australia – in 1988 as part of Australia’s Bicentenary celebrations to mark the anniversary of the arrival of the first fleet of British convict ships in Sydney, and 2006/07, during that summer’s Test series between the two countries. However, the Ashes urn is not the formal trophy played for between the two sides. The MCC commissioned a trophy that has been played for in series between Australia and England since 1998/99. That trophy is a larger replica of the urn in Waterford Crystal.

LIFE Photo Collection

The matter of The Ashes was largely forgotten for two decades after the tour of Australia by Bligh’s side in 1882/83, but was revived after the 1903/04 series when Pelham Warner, who captained the England side, wrote a book on the tour called ‘How we recovered The Ashes’ . From that day forward, the series between Australia and England would be famously, lovingly known as The Ashes.

The Ashes by Getty Images Cricket Australia

The first photograph of the urn appeared in The Illustrated London News of January 1921 and the words stuck to the urn are “The Ashes” followed by a six-line verse: “When Ivo goes back with the urn, the urn; Studds, Steel, Read and Tylecote return, return; The welkin will ring loud; The great crowd will feel proud; Seeing Barlow and Bates with the urn, the urn; And the rest coming home with the urn.” The words are the fourth verse of a song lyric published in the Melbourne Punch (February 1, 1883) from a song called ‘Who’s in the cricket field’ .

Donald Bradman's Bat & Baggy Green (2016) by Getty Images Cricket Australia

The first 18 series between the teams, before the legend of The Ashes was born, featured 13 England wins. In the immediate aftermath of World War One, Australia won eight Tests in a row, including the first-ever clean sweep in a five-match series in 1920/21. The 1932/33 series in Australia saw England regain The Ashes courtesy of a 4-1 series success that featured the so-called ‘Bodyline’ tactic, with England’s fast bowlers often targeting the bodies of the Australian batsmen rather than their stumps. England’s captain Douglas Jardine developed the approach as a means of lessening the effectiveness of Australia’s greatest player, Donald Bradman. His fast bowlers, principally Harold Larwood and Bill Voce, were able to deliver the strategy extremely effectively.

Watercolour, L Hutton (2002) by Robert Ingpen Melbourne Cricket Club

That 1932/33 success would be England’s last series victory until 1953. The period immediately after World War Two was one of Australian dominance and featured the 1948 tour when Bradman’s side did not lose a single match; winning the Test series 4-0, producing the-then highest run-chase in history by scoring 3-404 at Headingley in Leeds, and becoming known as The Invincibles. Australia’s stranglehold on bragging rights was finally broken by Hutton’s side of 1953, the first of three successive series wins for England. In 1956, off-spin bowler Jim Laker took 19 wickets in a single match at Old Trafford in Manchester, the best figure in the history of Test cricket.

Dennis Lillee statue Melbourne Cricket Ground

Australia regained The Ashes in 1958/59 in a series marred by controversies over the legitimacy of bowlers’ actions. The team then protected The Ashes throughout the 1960s in a period that was characterised by defensive cricket, with three of the five series during that decade ending in stalemate. England stole back The Ashes in 1970/71 under the captaincy of Ray Illingworth; a series that featured seven Tests. The seventh was added to the schedule when one Test in Melbourne was abandoned due to rain after the toss and was replaced by a one-day match between the sides. This became the first-ever One-Day International. The 1970s featured an iconic series in 1974/75, in which Australia fast bowlers Jeff Thomson and Dennis Lillee terrorised England’s batsmen before, in 1977, the two sides contested a Centenary Test in Melbourne, 100 years after the first meeting. In a remarkable coincidence, the margin of victory for Australia – 45 runs – was the same as it had been in 1877.

Watercolour, D Randall & R Marsh (2002) by Robert Ingpen Melbourne Cricket Club

The 1977 match was an animated one. It included 11 wickets for Lillee, a brilliant 174 from England batsman Derek Randall, 110 not out from Rodney Marsh, the first Australian wicketkeeper to score a Test hundred against England, and an unforgettable cameo from Australian batsman Rick McCosker, who returned to the crease to partner Marsh to his hundred despite suffering a broken jaw earlier in the match. The 1977 series between the two sides in England, known as the Centenary Series, was won 3-0 by England and was the last before the onset of World Series Cricket; a rival competition to official internationals. It was created by broadcasting magnate Kerry Packer. He had many of the world’s best players take part in matches on his television channel after he failed to secure the broadcasting rights for Australia’s home international matches from the Australian Cricket Board (ACB). Both England and Australia opted not to select their World Series players during the stand-off between official and unofficial cricket and, when an agreement was reached between the ACB and Packer, it was marked by a three-match series in 1979/80. Because of the shortened nature of the series, the MCC decreed that the Ashes were not at stake. Australia won it 3-0.

Botham Resurrects England (2013-07-22) by Cricket Australia Cricket Australia

1981 saw another iconic series for England, inspired by all-rounder Ian Botham and fast bowler Bob Willis, fighting back from 0-1 down to win 3-1. Botham scored hundreds at Headingley in Leeds and Old Trafford in Manchester and took five wickets for one run to secure victory at Edgbaston in Birmingham, while Willis took a career-best eight wickets for 43 runs to win the Headingley match. Australia got its revenge in the return series in 1982/83, winning 2-1. England’s victory at Melbourne by a margin of just three runs was the narrowest in the history of matches between the teams until 2005.

Remembering the 2005 and 2007 Ashes Series (2009-06-24) by Cricket Australia Cricket Australia

Australia ended the 1980s by crushing England 4-0, which signified the start of another period of dominance for the team. Remarkably, Australia won every series between the two teams until 2005, when England triumphed 2-1, including a two-run victory in the second match at Edgbaston. That marked a volatile period of results, with Australia securing 5-0 whitewashes in the home series in 2006/07 and 2013/14. The former series saw the retirements of bowlers Shane Warne and Glenn McGrath, who took 352 career England wickets between them. England claimed victorious in 2009, 2010/11, 2013 and 2015; the 2010/11 success including three innings victories. Australia’s series win in 2017/18 meant the Aussies moved ahead of England in total series honours (33 to 32), and the team is well ahead of England in Tests won – 144 to 108, with 94 drawn.

Watercolour, D Bradman (2001) by Robert Ingpen Melbourne Cricket Club

Only five players have scored more than 3000 Test runs in Australia – England Tests: Donald Bradman (Aus) 5028 Jack Hobbs (Eng) 3636 Allan Border (Aus) 3548 David Gower (Eng) 3269 Stephen Waugh (Aus) 3200

From the vault: Warne's 8-71 at the Gabba (2015-09-12) by Cricket Australia Cricket Australia

20 bowlers have taken 100 or more wickets in Ashes contests. Unsurprisingly, Warne sits at the top of this list: Shane Warne (Aus) 195 Dennis Lillee (Aus) 167 Glenn McGrath (Aus) 157 Ian Botham (Eng) 148 Hugh Trumble (Aus) 141 Bob Willis (Eng) 128 Monty Noble (Aus) 115 Ray Lindwall (Aus) 114 Wilfred Rhodes (Eng) 109 Sydney Barnes (Eng) 106 Clarrie Grimmett (Aus) 106 Derek Underwood (Eng) 105 James Anderson (Eng) 104 Alec Bedser (Eng) 104 George Giffen (Aus) 103 Bill O’Reilly (Aus) 102 Charlie Turner (Aus) 101 Bobby Peel (Eng) 101 Terry Alderman (Aus) 101 Jeff Thomson (Aus) 100

The History of Cricket in Australia

Cricket australia, home turf: melbourne cricket ground, melbourne cricket ground, the long room portraits, melbourne cricket club, australia's unparalleled world cup history, australia's home of sport, the laws of the game of cricket, larger than life: mcg sporting statues, in search of the founders, aboriginal xi tour of england, the evolution of the mcg, the bronze doors.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

The iconography of the Ashes

As England and Australia meet again, Wisden Cricket Monthly writers pick their favourite photographs from past series

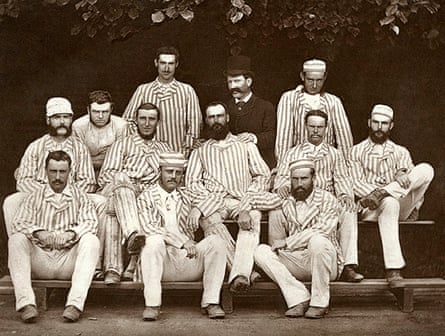

Location and photographer unknown. Circa 1880

The first Test match took place at Melbourne in March 1877. England’s touring party was organised by the business-savvy captain James Lillywhite and comprised 12 professionals, although this fell to 11 when wicketkeeper Ted Pooley, an inveterate gambler, was detained in New Zealand in a betting scandal. The match began at 1pm in front of 1,500 spectators. Charles Bannerman, who was born in Kent but raised in Sydney, faced the first ball, and when stumps were called four hours later, with the crowd having swelled to over 4,000, he was 126 not out from 166-6. The next day he pushed on to 165 before his middle finger was split and he retired hurt, his final score accounting for 67.3% of the team’s total. Remarkably, across the best part of 2,500 subsequent Test matches, that record remains intact. Australia won the match by 45 runs. Incredibly, a hundred years later, the one-off “Centenary Test” at the MCG in 1977 would throw up exactly the same result.

Australian frontiersmen

Location and photographer unknown. May 1878

The Australia team that toured England and North America in 1878 may not have played any international matches but the quality of the cricket and the pulling power of the likes of Fred Spofforth (on the left of the three standing figures) – considered the pre-eminent fast bowler of the era – ensured that the public would demand more. Four years later they would return, and in the first Test match ever staged in England, Spofforth’s 11-over spell at The Oval clinched a famous seven-run win. The result prompted the Sporting Life newspaper to mock up a front page “obituary”, in which “the body of English cricket would be cremated” and the “ashes” taken to Australia.

Florence and the urn

Location and photographer unknown. Circa 1890

In the autumn of 1882, Ivo Bligh voyaged to Australia with a 12-man squad made up of Oxbridge amateurs and four professionals, playfully declaring to the press and any Australian within earshot that he was going to “reclaim those ashes”. Legend has it that at Melbourne a group of Victorian women, including among them Florence Morphy, presented an urn to the English tourists, containing, so the story goes, the ashes of a burnt bail. Bligh’s team, shorn of WG Grace but still strong, won the series 2-1, and he and Florence were married a year later. She became the Countess of Darnley; and England-Australia Tests became The Ashes . England would hold the urn for the next six series, with WG Grace, who was part of that infamous 1882 defeat, getting revenge on Spofforth with 170 at The Oval in 1886.

The Oval, London. August, 1905. By Reinhold Thiele

The Oval crowd, dressed in its finery, stands to watch the fifth Test of the 1905 Ashes. The photograph was taken by Reinhold Thiele, the pioneering German flashlight photographer. (Thiele, who came to England in 1878 to study photography, became one of the first press photographers, initially specialising in football teams before focusing his lens on wider sporting scenes, and later, portraits of prominent celebrities.)

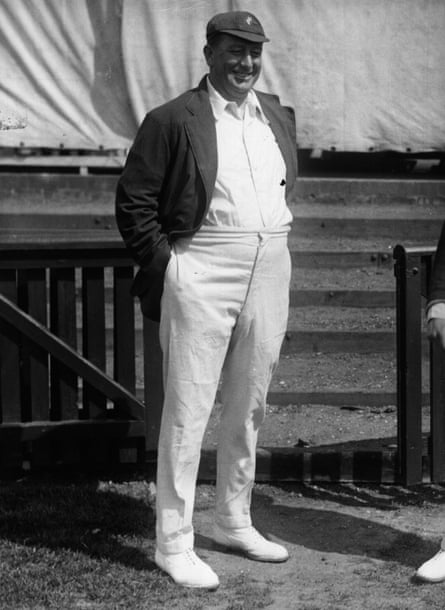

The Big Ship

Trent Bridge, Nottingham. May 1921. Photographer unknown

Warwick Armstrong ruled Australian cricket through much of the early part of the century. Known as “The Big Ship” due to his immense physique, Armstrong was a garrulous and hugely popular Victorian, reputedly as gifted at Australian rules football as he was at cricket. He first debuted for Australia in 1902 but was only given the Test captaincy when cricket resumed after the Great War. By then the wrong side of 40, he masterminded a 5-0 whitewash of the touring MCC side in 1920-21, making three centuries himself and strolling out to bat at Sydney in the final innings of the series after drinking whisky with his mates all afternoon in the members’ bar. (It was all good practice for his later career as an agent for a scotch whisky distributor.) He then oversaw a 3-0 win in England the following summer, before retiring undefeated, with eight wins from his 10 Tests in charge.

Cricketers on tour

Queensland, Australia. December 1928. Photographer unknown

A day at the beach for players and partners midway through the Ashes of 1928-29, featuring members of both teams. Wally Hammond (third left), Patsy Hendren (centre), and George Geary (fourth right) formed the core of England’s successful retention of the urn that Australian summer. Hammond’s 905 runs in the series was a momentous tally. He was generally considered at that point to be the greatest batter not just of his time, but of all those who preceded him. The mark, from nine innings, should have stood forever. It stands today comfortably beyond the reach of all-but-one challengers, and yet the record lasted less than two years. Don Bradman, pictured second right, would manage a couple of smallish centuries in Australia’s 4-1 defeat in 1928-29 – his first tons in the Baggy Green – but two summers later in England he would obliterate Hammond’s record, and much of his pride, with 974 runs in his first full Ashes. Hammond, who registered 113 and 60 and not much else in the series, would rarely be free of Bradman’s shadow for the rest of his life.

The fateful scoreboard

The Exhibition Ground, Brisbane. 5 December 1928. Photographer unknown

The tale of the first Test of the 1928-29 Ashes makes for desperate reading for Australia. Defeat by 675 runs remains to this day by far their biggest runs defeat in the history of the contest.

Bradman’s world record

Headingley, Leeds. July 1930. Photographer unknown

The hordes congregate around the greatness of one man. Bradman, then just 21, departs the field 309* after day one of the third Test. That night in his diary he wrote, with presumably comic dryness (although Bradman was not renowned for his wit): “We won the toss and batted. Archie [Jackson] out for one. I followed, and at stumps was 309 not out.” The following day he would take his score up to 334. His series tally of 974 runs remains by some distance the highest individual return in the Ashes. Australia won the series 2-1.

The Gabba, Brisbane. March, 1933. Photographer unknown

By the third Test at Adelaide, “Bodyline” had come to dominate and scandalise the contest. On day two, when Australia’s captain Bill Woodfull was hit over the heart by Larwood, Jardine was reported to have called out “Well bowled, Harold!” as Woodfull, surrounded by fielders, struggled for regain his breath. When Woodfull eventually resumed, and Jardine reverted to a leg-side-heavy field, the crowd was incensed, threatening to riot. Although Jardine later said he regretted the decision, at the time he was unrepentant. The England team manager Plum Warner later visited the Australian dressing room and was rebuffed by Woodfull, who said: “I don’t want to see you, Mr Warner. There are two teams out there. One is trying to play cricket and the other is not.”

With a tear in his eye

The Oval, London. August 1948. Photographer unknown

Although they were never afforded full Test status, the five “Victory Tests” in the summer of 1945 were nonetheless a cherished chapter in Anglo-Australian cricket, unfolding in a spirit of euphoria following the end of the second world war. Three years later Australia were back as a full representative side, led by Bradman in his final series. Here he departs for the final time, bowled second ball by an Eric Hollies googly to leave his Test average tottering at 99.94 . Legend has it that he was unable to dry his eyes following the standing ovation that greeted his walk to the middle. On commentary John Arlott was moved to silence, letting the applause of the crowd carry Bradman to the pavilion. That summer, Bradman’s Australians went unbeaten across 34 first-class matches, assuming the title of the “Invincibles”.

The era of Richie

SCG, Sydney. January 1959. Photographer unknown

Smooth, sharp-witted and tactically astute, the leg-spinning all-rounder Richie Benaud was Australia’s first great post-war captain and the biggest influence on the world game at the time. The 1958-59 series was a personal triumph: with the ball he claimed 31 wickets, and he led with great attacking instincts to pulverise a conspicuously poor MCC team by four Tests to one. The bigger challenge would be the return scrap in England in 1961. A seesawing series eventually fell to the tourists in the fourth Test at Old Trafford, when Benaud came up against the young Ted Dexter in the fourth innings. Chasing 256 to win, England were going well at 150-2 before Benaud chose to go round the wicket, immediately removing Dexter for 76 and then the captain Peter May for a duck. The squeeze was on, and Benaud ran through the lower order to claim six wickets and a 54-run win. With the Ashes retained, the series win was duly secured with a draw at The Oval.

The rise of the sandshoe crushers

MCG, Melbourne. December 1974. By Patrick Eagar

The 1974-75 tour was a hostile bloodbath. After the events of four years before, Australia plotted revenge with their own policy of short stuff. Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson, technician and tearaway, were their chosen enforcers, and Thomson’s bloodlust in particular was insatiable; homing in on skulls and toes with little in between, he declared that he’d rather see claret spilt on the pitch than numbers in the wickets column. Spurred on by his hard-nosed skipper Ian Chappell, Thomson ripped through England’s line-up, claiming 33 wickets as Australia won four of the first five Tests. Only when Lillee and Thomson were missing for the last match, did England register a flimsy consolation win.

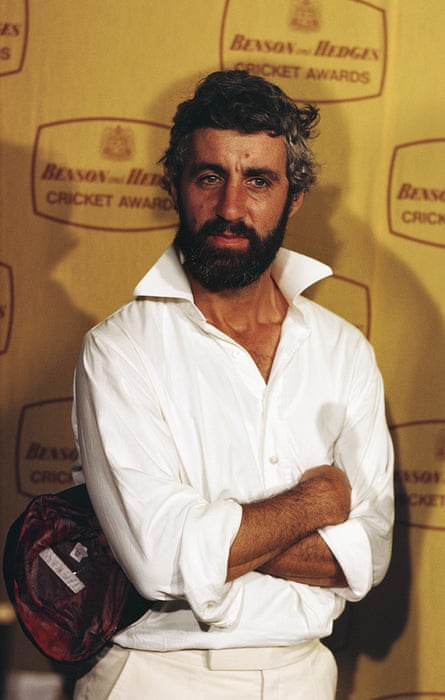

Location and photographer unknown. January 1980

The England captain, sporting the beard that spooked the Aussie public into nicknaming him “Ayatollah”, masterminded a 5-1 Ashes win in 1978-79 against a team ravaged by defections to Kerry Packer’s World Series Cricket . A year later, the two teams met in a hastily arranged three-Test rubber which took place after an agreement was reached by the Australian cricket board and the WSC defectors. The series, which fell outside of the official Ashes story, was won 3-0 by Australia, but it has been largely consigned to history, with Dennis Lillee’s infamous aluminium bat its only footnote. Although Brearley never made a Test hundred he nonetheless occupies a unique position in Ashes folklore, as the captain who orchestrated the 1978-79 win and the 1981 turnaround.

Bustlin’ Bob

Headingley, Leeds. July 1981. By Patrick Eagar

Australia’s Ray Bright glances back at his splayed stumps, rearranged by a rampant Bob Willis, whose 8-43 has just toppled the tourists for 111. His spell wraps up a pulsating 18-run victory – just the second time in Test history when a team has won having followed-on. As Brearley’s men scamper off the field to dodge the invading fans, Australia traipse away to contend with the series being level at 1-1, and a delivery of £7,500 after a couple of the players decided to place mid-match bets on England winning at 500-1. Subsequent wins at Edgbaston and Old Trafford put ‘Botham’s Ashes’ into the history books.

Get past that

Lord’s, London. July 1989. By Patrick Eagar

Patrick Eagar is the godfather of modern cricket photographer, an aficionado of the game first and foremost, and Steve Waugh’s forward defensive at Lord’s is the sort of photo that only a true lover of cricket would think to take. Waugh came to England that summer without a Test century to his name. He rectified that at Leeds in the first Test, helping Australia to an innings victory, and then went to Lord’s and made another. He wasn’t dismissed until the third match of a series that Australia would win 4-0. Urn reclaimed, they didn’t relinquish it for 16 years.

Be afraid, be very afraid

Old Trafford, Manchester. June 1993. By Patrick Eagar

Shane Warne in action on his first Ashes tour, at the ground where he had already produced the “Ball of the Century” from his first delivery. Warne’s 34 wickets helped Australia claim a 4-1 victory and kickstarted a career of utter dominance over English techniques and minds. He retired in January 2007 as one of Wisden’s five Cricketers of the Century; 195 of his 708 Test wickets came in Ashes Tests.

Dare to believe

Edgbaston, Birmingham. June 1997. By Laurence Griffiths

A nine-wicket win in the first Test prompts excited talk of an English renaissance. Nasser Hussain makes a double hundred and Graham Thorpe 138 as England dominate the visitors, before the trio of Glenn McGrath, Shane Warne and Steve Waugh get to work.

Jones’ Gabba nightmare

The Gabba, Australia. November 2002. By Darren England

Having inserted Australia to the surprise of everyone, Nasser Hussain could only watch in horror as he lost Simon Jones to injury shortly after lunch on the opening day of the series. Sliding for a ball on the sandy Gabba outfield, the fast bowler’s studs got caught in the turf, rupturing the anterior cruciate ligament in his right knee, an injury which kept him out of the game for over a year. The visitors went on to lose by 384 runs and eventually succumbed to an eighth consecutive Ashes series defeat, but when the two sides next met England would be a considerably more potent force, with Jones part of a formidable four-pronged pace attack. “It made me come back a better bowler,” he later said of his injury. “I was young and raw at the time and bowling a few miles an hour quicker, but my skillset was far superior when I came back.”

KP’s genius

The Oval, England. September 2005. By Philip Brown Kevin Pietersen drinks in the adulation having effectively secured England’s first Ashes win for 18 years, rescuing his side with a scintillating 158 following a second-innings collapse which threatened to scupper their chances at the last. Playing in his maiden Test series, Pietersen scored 473 runs at 52.55.

England’s perfect day

Melbourne, Australia. December 2010. Photographer Mark Dadswell The momentum appeared to be with Australia after a thumping victory at the WACA had levelled the series at 1-1 with two to play, but by the conclusion of day one of the Boxing Day Test it was clear that England would retain the Ashes. Andrew Strauss, who later described this as England’s “perfect day”, bravely chose to field first and then watched his seamers wreak havoc under cloudy skies, Ricky Ponting the third wicket to fall after edging Chris Tremlett to Graeme Swann at second slip. The hosts were 58-4 at lunch and all out for 98 before tea. By stumps, England had opened up a lead of 59 without having lost a wicket in one of the most one-sided days of cricket between the two old rivals. After innings defeats at Melbourne and Sydney gave England their first overseas Ashes win in 24 years, Ponting called time on his tenure as captain.

Facing up to Johnson

The Gabba, Brisbane, Australia. November, 2013. Photographer Scott Barbour Stuart Broad nervously prepares to face Mitchell Johnson as the left-arm quick steams in on day two of the first Test at Brisbane. It’s a match Johnson dominates with ball and bat, taking nine wickets and hitting a crucial half-century to inspire Australia to a crushing 381-run win. That performance sets the tone for the series. The revitalised fast bowler, who cut such a forlorn figure when England visited three years earlier, shatters stumps and reputations across five matches of relentless ferocity, claiming 37 wickets at 13.97 and three Player of the Match awards.

The miracle of Headingley 2.0

Headingley, Leeds, England. August 2019. Photographer Stu Forster

Jack Leach’s face sums up the emotion of a nerve-shredding day, as Ben Stokes creams Pat Cummins to the cover boundary to pull off the unthinkable, scripting a one-wicket win that keeps England’s hopes of regaining the Ashes alive.

Wisden Cricket Monthly has produced an Ashes digital special edition. You can read it for free here , and it’s compatible with all major devices. With contributions from writers such as Adam Collins, Tom Holland, Sam Perry, Alison Mitchell, Tim Key, Rob Smyth, James Wallace and Felix White, it’s the perfect companion to the series.

- Guardian Sport Network

- Australia cricket team

- Australia sport

- England cricket team

- Ashes 2021-22

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 26 May 2023

The dentist who helped save cricket in the 1930s

British Dental Journal volume 234 , page 715 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

208 Accesses

Metrics details

Cricket fans among our readers may be surprised to hear that an Australian dentist called Robbie Macdonald was involved in the aftermath of Bodyline, a cricketing tactic devised by the English cricket team for their 1932-33 Ashes tour of Australia to curb Don Bradman, an Australian cricketer widely acknowledged as the greatest batsman of all time.

© VasjaKoman/DigitalVision Vectors/Getty

Bodyline delivery, also known as 'fast leg theory bowling', is where the cricket ball was bowled swiftly at the body of the batsman in the expectation that when they defended themselves with their bat, a resulting deflection could be caught by a fielder standing close by on the leg side.

During the 1932-33 Ashes tour, Anglo-Australian relations were under threat due to the injuries caused by the English team's strategy. It was Dr Robbie Macdonald, a dentist and cricketer who became Australia's representative at the Imperial Cricket Council in London, who helped steer a 'truce'.

An article in the February 2023 issue of The Cricketer all about 'The man who killed Bodyline' reads:

'Australia was very, very displeased at England's brutal bodyline bowling in that tumultuous summer of 1932/33. The only course left open to the "colony" was to drop a hint - polite or otherwise - that the next tour of England might well be cancelled.

'Macdonald, aged 63, diplomatically offered something equally dramatic: if there was no guarantee to ban this vicious bodyline bowling, then Australia might still tour, but its touring party would include a squad of big and nasty fast bowlers who would show England first-hand what this ghastly bodyline was like...

'In due course the intrepid Macdonald carried the day [...] Ashes cricket was patched up and continued on its eventful way.'

Thank you to BDJ reader Gary Whittle for bringing this story to our attention ahead of this year's Ashes series in June.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

The dentist who helped save cricket in the 1930s. Br Dent J 234 , 715 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-023-5921-7

Download citation

Published : 26 May 2023

Issue Date : 26 May 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-023-5921-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

What is Bodyline Bowling – The Story of the 1932/33 Ashes Series

Table of Contents

Ashes contests between England and Australia have often been fiery affairs but nothing has come close to the 1932/33 series down under. Hostile, intimidatory bowling from the English attack led to some serious ill feeling which is still discussed over 85 years later.

What is Bodyline Bowling?

Bodyline is also known as leg theory and that gives a clue as to what it’s about. The intention is for a right arm bowler to deliver around the wicket into the batsman’s body. The ball is short pitched and the aim is to intimidate the batter and to get them to fend off the delivery towards fielders on the leg side.

To get the idea, check the video below.

The Evolution of Bodyline Bowling

Many may think that bodyline was born in that 1932/33 series but the practise has been around for a lot longer. By the start of the 20th century, a number of bowlers were beginning to use leg theory as a legitimate tactic.

The deliveries weren’t necessarily short but the bowler would often direct the ball at, or outside of leg stump. This made it difficult for the batsman to play a shot anywhere but on the leg side. That leg side would be packed with fielders and the aim for the bowling team was for the batters to hit the ball in their direction.

The next big development in the history of bodyline bowling came in the 1920s . It was at this point that leg theory started to involve shorter balls that were directed at the batsman’s body . It’s said that bodyline became prevalent in Australia and that captains were split as to whether the tactic should be used.

This progress exploded in 1932/33 when bodyline was used extensively during England’s Ashes tour . Under the guidance of controversial captain Douglas Jardine, fast bowlers Harold Larwood and Bill Voce were the main exponents of short pitched leg theory.

Bowling to a packed leg side field, the England side of that season won the Ashes but left behind plenty of ill feeling with battered and bruised Australian batsmen brushed aside.

The Spirit of Cricket

Even in the 19th century, the concept of leg theory was considered to be ungentlemanly and against the spirit of the game . By the time that the bodyline series came along in 1932, most people inside cricket felt that the English bowlers had definitely crossed a line.

Don Bradman

With a test batting average just below a perfect 100, most people in the game feel that Sir Don Bradman was the greatest batsman that cricket has ever seen . In the 1930s, the Australian was at the height of his powers and opposition teams were looking at new ways in which to combat his brilliance.

In the previous series between England and Australia in 1930, Bradman had scored 974 runs in five tests at an average above 139 and that’s a record that stands to this day. Clearly his was a key wicket and, as part of their plans to dismiss Bradman in 1932/33, England brought in their bodyline tactic.

England’s Bowling Tactic in the 1930s

England’s touring party of 1930 used a more sustained and hostile form of leg theory than had previously been seen. When the tactic was used, there was no real intention to bowl at the stumps. The bowlers would pitch short with a view to getting the batsman to fend a catch into the packed leg side field or, the batter would be hit and therefore intimidated.

The practise was used in two warm up matches and there was some success. Crucially, Don Bradman played in those games and failed to impress in either of them. The tourists had the green light to continue with bodyline and it was to have a devastating effect in the test matches that followed.

While controversy had been simmering in the first two games, it exploded in the third test. This was the game where Australia’s Bill Woodfull was struck a sickening blow in the chest while Bertie Oldfield suffered a fractured skull. The unpleasant side of bodyline was now clear for all to see.

Ultimately, it could certainly be argued that bodyline was successful in the sense that England won the series by four tests to one. The Australian Cricket Board stated that they considered the tourists to have bowled fairly but not everyone was in agreement.

Australia’s cricket watching public were appalled by the tactics and Englishmen were also unhappy. The concern even spread to the English tour manager, Sir Pelham Warner. It was largely because of this split opinion that the 1930s form of bodyline was never seen again but that was also due to a change in the game’s laws.

Controversy Over Bodyline Bowling

There are a number of reasons why bodyline in 1932 and hostile leg theory in the modern day are considered to be controversial. Firstly, there is that question of the spirit of the game: The task of the bowler is to dismiss the batsman using all of their skills, including seam and swing.

For many, the first aim of bodyline bowling is not to dismiss the batsman but to intimidate them . Back in that 1932/33 Ashes series, there were plenty of dismissals secured by Larwood and Voce but Australian batsmen also suffered injury on occasions and had to retire.

Then there is the question of hostile bowling in general. Don Bradman was the best batsman of his, and possibly any era, but bodyline was used indiscriminately in 1932/33. All batters were targets as far as the England attack were concerned.

The question of intimidation is still discussed in the modern day. Until relatively recently, it was common for bowlers not to deliver fast bouncers at tail enders but that doesn’t seem to be the case today. Those short balls may not involve a leg theory line but the spectre of bodyline still remains in this type of discussion.

In the main, it’s all about playing fair and upholding the spirit of the game: Ever heard the expression, It’s Just not Cricket?

Modern Examples of Bodyline Bowling

There are isolated occasions where leg theory is specifically used and we saw an example of this as recently as 2021. In the test series between India and Australia, the Australian bowlers were having a tough time dismissing the obdurate batsman Cheteshwar Pujara.

A patient accumulator of runs, Pujara had faced more deliveries than any other batter in the series and pace bowler Pat Cummins decided to do something about it. From a ‘round the wicket’ angle, Cummins started to bowl short and into Pujara’s body with the result that the batsman was hit on no fewer than nine occasions over the course of a single day.

Other bowlers got in on the act but Cummins was the main aggressor, hitting Pujara no fewer than six times.

Leg theory can be used as a negative tactic and it’s not necessarily exclusive to fast bowlers. I can remember England being frustrated so much by the great Sachin Tendulkar that left arm slow bowler Ashley Giles bowled outside of his leg stump.

Ultimately, the tactics worked as Tendulkar was stumped for the first time in his career as the frustration got the better of him. It’s happened on other occasions with less success and I can confidently say that it makes for some very dull cricket.

This isn’t bodyline in the strictest sense as a change to the laws stops teams replicating England’s tactics of 1932/33 but it can certainly be classified as ‘leg theory’.

Consequences of Bodyline Bowling

There was considerable ill feeling between England and Australia in the wake of the 1932/33 Ashes and the series had a direct impact on the careers of certain individuals. In the second test, the Nawab of Pataudi made a century for England but he never played again after refusing to move to a leg side fielding position.

Skipper Jardine is said to have stated that ‘his highness is a conscientious objector’. Harold Larwood was asked to write an apology letter and he refused, meaning that he never played test cricket again after 1933.

As for Douglas Jardine, his final test came a year later in 1934 but it’s fair to say that his reputation wasn’t exactly enhanced.

Changes to the Laws of Cricket

Shortly after that Ashes series, a ruling was put in place stating that no more than two fielders could be placed behind square on the leg side , and that was a key tactic for Douglas Jardine’s men.

Later on, additional laws restricted the number of bouncers that a bowler could send down during an over. While this isn’t directly related to bodyline, there is a connection to that 1932/33 series and the ongoing question of intimidatory bowling.

The MCC also stated that Bodyline breached the spirit of the game and the English side was widely criticised within the sport. In general, while the tactics won England a test series, few people in the game are happy with the way in which the Ashes were regained in 1932/33.

Is Bodyline Bowling Legal?

While cricket laws don’t specifically name bodyline, the practise that was undertaken by England in 1932/33 has effectively been outlawed. We’ve seen the ruling relating to fielders behind square leg and that would make it impossible to replicate the English bowler’s tactics from that Ashes series.

In the present day, as we have seen with the contest between Pat Cummins and Cheteshwar Pujara, bodyline can still be applied but it’s very different from the type of contest seen back in the 1930s.

Related Posts

Cricket Formats – Let’s Explore the 4 Types of Cricket

As the sport of cricket has evolved, organisers have continually introduced new formats in order to attract a new audience. Traditionally, test and first class…

Is Cricket an Olympic Sport? – Cricket at the Summer Games

Cricket is a global sport, now more than ever. This british sport is now played in more parts of the world than ever before and…

RR won by 7 wickets (with 6 balls remaining)

Pakistan won by 9 runs

DC won by 10 runs

ZIM Women won by 8 wickets (with 27 balls remaining)

SL Women won by 10 wickets (with 59 balls remaining)

Day 2 - Essex trail by 44 runs.

Day 2 - Hampshire trail by 177 runs.

Day 2 - Warwickshire trail by 329 runs.

Day 2 - Worcester trail by 202 runs.

Day 2 - Gloucs lead by 68 runs.

Day 2 - Leics trail by 356 runs.

Day 2 - Derbyshire trail by 260 runs.

SE Stars won by 71 runs (D/L method)

Sunrisers won by 7 wickets (with 127 balls remaining)

Storm won by 66 runs

Vipers won by 70 runs (D/L method)

Uganda Women won by 8 wickets (with 10 balls remaining)

Neth Women won by 100 runs

Nepal won by 4 wickets (with 2 balls remaining)

Gujarat Titans

Royal Challengers Bengaluru

Match starts in 5 hrs 47 mins

Chennai Super Kings

Sunrisers Hyderabad

Match yet to begin

Pakistan Women

West Indies Women

West Indies A

Match starts in 2 hrs 17 mins

Bangladesh Women

India Women

Australia vs England , 2nd Test at Melbourne , , Dec 30 1932 - Full Scorecard

Australia won by 111 runs

Bradman back with a bang

A match report from The Cricketer of the 2nd Test at Melbourne

Australia v England 1932-33

In the second Test Match, at Melbourne, Jardine again lost the toss, but England started even better than they had done at Sydney and, at the end of the first day, Australia had seven men out for 194

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

A cricket team representing England toured Australia in the 1932-33 season. The tour was organised by the Marylebone Cricket Club and matches outside the Tests were played under the MCC name. The tour included five Test matches in Australia, and England won The Ashes by four games to one. The tour was highly controversial because of the bodyline bowling tactics used by the England team under ...

Check The Ashes live score 1932/33, squads, match schedules, The Ashes points table, fixtures, updates, photos, and videos on ESPNcricinfo. ... 1933, England [Marylebone Cricket Club] tour of ...

The Third Test of the 1932-33 Ashes series was one of five Tests in a cricket series between Australia and England. ... While Jardine's unfriendly approach and superior manner caused some friction with the press and spectators, the early tour matches were uncontroversial and Larwood and Voce had a light workload in preparation for the Test ...

MATCH DETAILS. Get cricket scorecard of 3rd Test, AUS vs ENG, England [Marylebone Cricket Club] tour of Australia 1932/33 at Adelaide Oval dated January 13 - 19, 1933.

Bodyline. The 1932-33 Ashes series is the most controversial in the history of Australian-English Test cricket. The English team, desperate to contain Australian batsman Don Bradman and win back the Ashes, adopted a controversial strategy. Technically known as 'fast leg theory', it was better known as 'bodyline'.

The MCC tour of Australia and New Zealand in 1932/33 was one of the finest - and one of the most controversial - Test series ever played and was nicknamed 'The Bodyline Series.'. When Wally Hammond and Bob Wyatt put on 125 for the third wicket to gain victory for England by eight wickets in Sydney, it capped a remarkable winter for the ...

Get 1932/33 The Ashes schedule, fixtures, scorecard updates, and results on ESPNcricinfo. Track latest match scores, schedule, and results of The Ashes 1932/33.

England's cricketers beat Australia in the first Test of the 1932 Ashes series on this day - in a tour they won 4-1 after using controversial bodyline bowling t. Home Olympics.

The Bodyline tour of 1932-33 remains the most controversial in Ashes history. But in his analysis of the series, the great Neville Cardus found much to praise in England's relentless strategy.</p>

Tibby Cotter of Australia bowling to Wilfred Rhodes in the second Ashes Test at Melbourne Cricket Ground. England won the match by 8 wickets. Despite losing the first Test at Sydney, England hit ...

The matter of The Ashes was largely forgotten for two decades after the tour of Australia by Bligh's side in 1882/83, but was revived after the 1903/04 series when Pelham Warner, who captained the England side, wrote a book on the tour called 'How we recovered The Ashes'. From that day forward, the series between Australia and England would be famously, lovingly known as The Ashes.

Australia won an Ashes series for the first time in 1891-92, when it beat England 2-1. The 1932-33 tour was known as the " Bodyline series" as, in response to the talented Australian batsman Don Bradman , England developed a tactic of bowling quickly at the body of the batsmen with most of the fielders placed in a close ring on the leg ...

Bodyline. Bodyline, also known as fast leg theory bowling, was a cricketing tactic devised by the English cricket team for their 1932-33 Ashes tour of Australia. It was designed to combat the extraordinary batting skill of Australia's leading batsman, Don Bradman. A bodyline delivery was one in which the cricket ball was bowled at pace, aimed ...

Classic Ashes Series: Bodyline 1932-33. By KirbyMeehan. Modified Feb 24, 2014 16:23 IST. Follow Us Discuss. England captain Douglas Jardine making a point to his players following the fall of an ...

Get cricket scorecard of 4th Test, AUS vs ENG, England [Marylebone Cricket Club] tour of Australia 1932/33 at Brisbane Cricket Ground, Woolloongabba, Brisbane dated February 10 - 16, 1933.

Shane Warne in action on his first Ashes tour, at the ground where he had already produced the "Ball of the Century" from his first delivery. Warne's 34 wickets helped Australia claim a 4-1 ...

During the 1932-33 Ashes tour, Anglo-Australian relations were under threat due to the injuries caused by the English team's strategy. It was Dr Robbie Macdonald, a dentist and cricketer who ...

MATCH DETAILS. Get cricket scorecard of 1st Test, AUS vs ENG, England [Marylebone Cricket Club] tour of Australia 1932/33 at Sydney Cricket Ground dated December 02 - 07, 1932.

This progress exploded in 1932/33 when bodyline was used extensively during England's Ashes tour. Under the guidance of controversial captain Douglas Jardine, fast bowlers Harold Larwood and Bill Voce were the main exponents of short pitched leg theory. Bowling to a packed leg side field, the England side of that season won the Ashes but left ...

Results. To view more info on a match, click the View button. Ashes Series - Game 1. 1932. Jun 6. Australia. 6. -. England (GB)

Get cricket scorecard of 5th Test, AUS vs ENG, England [Marylebone Cricket Club] tour of Australia 1932/33 at Sydney Cricket Ground dated February 23 - 28, 1933.

Get cricket scorecard of 2nd Test, AUS vs ENG, England [Marylebone Cricket Club] tour of Australia 1932/33 at Melbourne Cricket Ground dated December 30, 1932 - January 03, 1933.