Journey to the West

Journey to the West (西遊記, Xīyóujì in Mandarin Chinese and Saiyūki in Japanese) is a 16th-century Chinese legend and one of the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature , which Dragon Ball is loosely based upon. Originally published anonymously in the 1590s during the Ming Dynasty, it has been ascribed to the scholar Wú Chéng'ēn since the 20th century, even though no direct evidence of its authorship survives.

The tale is also often known simply as Monkey . This was one title used for a popular, abridged translation by Arthur Waley. The Waley translation has also been published as Adventures of the Monkey God ; and Monkey: [A] Folk Novel of China ; and The Adventures of Monkey .

- 1.1 Synopsis

- 1.2 Historical context

- 1.3 Relation to Dragon Ball

- 2.1 Tripitaka or Xuánzàng

- 2.2 Monkey King or Sūn Wùkōng

- 2.3 Zhū Bājiè

- 2.4 Shā Wùjìng

- 3 List of Demons

- 4 Notable English-language translations

- 5.3 Live-action television

- 5.4.1 Works referencing Journey to the West

- 6 References

- 7 External links

Overview [ ]

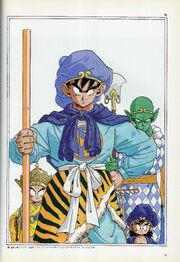

Dragon Ball characters depicted as Journey to the West characters ( Toriyama - The World & Daizenshuu 1 )

The novel is a fictionalized account of the legends around the Buddhist monk Xuánzàng's pilgrimage to India during the Táng dynasty in order to obtain Buddhist religious texts called sutras. On instruction from the Buddha, the Bodhisattva Guānyīn gives this task to the monk and his three protectors in the form of disciples: namely Sūn Wùkōng, Zhū Bājiè and Shā Wùjìng; together with a dragon prince who acts as Xuánzàng's horse mount. These four characters have agreed to help Xuánzàng as an atonement for past sins.

Some scholars propose that the book satirizes the effete Chinese government at the time. Journey to the West has a strong background in Chinese folk religion, Chinese mythology and value systems; the pantheon of Taoist deities and Buddhist bodhisattvas is still reflective of Chinese folk religious beliefs today.

Part of the novel's enduring popularity comes from the fact that it works on multiple levels: it is a first-rate adventure story, a dispenser of spiritual insight, and an extended allegory in which the group of pilgrims journeying toward India stands for the individual journeying toward enlightenment.

Synopsis [ ]

Gohan as the Monkey King (" Detekoi Tobikiri ZENKAI Power! ")

The novel comprises 100 chapters that can be divided into four very unequal parts. The first, which includes chapters 1–7, is really a self-contained prequel to the main body of the story. It deals entirely with the earlier exploits of Sūn Wùkōng, a monkey born from a stone nourished by the Five Elements, who learns the art of the Tao, 72 polymorphic transformations, combat and secrets of immortality, and through guile and force makes a name for himself as the Qítiān Dàshèng , or "Great Sage Equal to Heaven". His powers grow to match the forces of all of the Eastern (Taoist) deities, and the prologue culminates in Sūn's rebellion against Heaven, during a time when he garnered a post in the celestial bureaucracy. Hubris proves his downfall when the Buddha manages to trap him under a mountain for five hundred years.

Only following this introductory story is the nominal main character, Xuánzàng, introduced. Chapters 8–12 provide his early biography and the background to his great journey. Dismayed that "the land of the South knows only greed, hedonism, promiscuity, and sins", the Buddha instructs the Bodhisattva Guānyīn to search Táng China for someone to take the Buddhist sutras of "transcendence and persuasion for good will" back to the East. Part of the story here also relates to how Xuánzàng becomes a monk (as well as revealing his past life as the "Golden Cicada" and comes about being sent on this pilgrimage by the Emperor Táng Tàizōng, who previously escaped death with the help of both an underworld official and Xuánzàng).

The third and longest section of the work is chapters 13–99, an episodic adventure story which combines elements of the quest as well as the picaresque. The skeleton of the story is Xuánzàng's quest to bring back Buddhist scriptures from Vulture Peak in India, but the flesh is provided by the conflict between Xuánzàng's disciples and the various evils that beset him on the way.

The scenery of this section is, nominally, the sparsely populated lands along the Silk Road between China and India, including Xinjiang, Turkestan, and Afghanistan. The geography described in the book is, however, almost entirely fantastic; once Xuánzàng departs Cháng'ān, the Táng capital and crosses the frontier (somewhere in Gansu province), he finds himself in a wilderness of deep gorges and tall mountains, all inhabited by flesh-eating demons who regard him as a potential meal (since his flesh was believed to give Immortality to whoever eats it), with here and there a hidden monastery or royal city-state amid the wilds.

The episodic structure of this section is to some extent formulaic. Episodes consist of 1–4 chapters, and usually involve Xuánzàng being captured and his life threatened, while his disciples try to find an ingenious (and often violent) way of liberating him. Although some of Xuánzàng's predicaments are political and involve ordinary human beings, they more frequently consist of run-ins with various goblins and ogres, many of whom turn out to be the earthly manifestations of heavenly beings (whose sins will be negated by eating the flesh of Xuanzang) or animal-spirits with enough Taoist spiritual merit to assume semi-human forms.

Chapters 13–22 do not follow this structure precisely, as they introduce Xuánzàng's disciples, who, inspired or goaded by Guānyīn, meet and agree to serve him along the way, in order to atone for their sins in their past lives.

- The first is Sun Wukong, or Monkey, previously "Great Sage Equal to Heaven" and literally "Monkey Awakened to Emptiness", trapped by Buddha for rebelling against Heaven. He appears right away in Chapter 13. The most intelligent and violent of the disciples, he is constantly reproved for his violence by Xuánzàng. Ultimately, he can only be controlled by a magic gold band that the Bodhisattva has placed around his head, which causes him excruciating pain when Xuánzàng says certain magic words.

- The second, appearing in 19, is Zhu Bajie, literally "Pig of Eight Precepts", sometimes translated as Pigsy or just Pig. He was previously Marshal Tīanpéng, commander of the Heavenly Naval forces, banished to the mortal realm for flirting with the Princess of the Moon Chang'e. He is characterized by his insatiable appetites for food and sex, and is constantly looking for a way out of his duties, but is always kept in line by Sūn Wùkōng and also doubles as comic relief.

- The third, appearing in chapter 22, is the river-ogre/kappa Sha Wujing, also translated as Friar Sand or Sandy and literally "Sand Awakened to Purity". He was previously Great General who Folds the Curtain, banished to the mortal realm for dropping (and shattering) a crystal goblet of the Heavenly Queen Mother. He is a quiet but generally dependable character, who serves as the straight foil to the comic relief of Sūn and Zhū who despite this trait, is the nicest out of his two other fellow disciples.

- Possibly to be counted as a fourth disciple is the third prince of the West Sea Dragon King, Yùlóng Sāntàizǐ, who was sentenced to death for setting fire to his father's great pearl that was a gift from the Jade Emperor. He was saved by Guānyīn from execution to stay and wait for his call of duty. He appears first in chapter 15, but has almost no speaking role, as throughout most of the story he appears in the transformed shape of a horse that Xuánzàng rides on. Though some adaptations have managed to expand his role to some degrees.

Chapter 22, where Shā is introduced, also provides a geographical boundary, as the river of quicksand that the travelers cross brings them into a new "continent". Chapters 23–86 take place in the wilderness, and consist of 24 episodes of varying length, each characterized by a different magical monster or evil magician. There are impassably wide rivers, flaming mountains, a kingdom ruled by women, a lair of seductive spider-spirits, and many other fantastic scenarios. Throughout the journey, the four brave disciples have to fend off attacks on their master and teacher Xuánzàng from various monsters and calamities.

It is strongly suggested that most of these calamities are engineered by fate and/or the Buddha, as, while the monsters who attack are vast in power and many in number, no real harm ever comes to the four travelers. Some of the monsters turn out to be escaped heavenly animals belonging to bodhisattvas or Taoist sages and spirits. Towards the end of the book there is a scene where the Buddha literally commands the fulfillment of the last disaster, because Xuánzàng is one short of the eighty-one disasters he needs to attain Buddhahood.

In chapter 87, Xuánzàng finally reaches the borderlands of India, and chapters 87–99 present magical adventures in a somewhat more mundane (though still exotic) setting. At length, after a pilgrimage said to have taken fourteen years (the text actually only provides evidence for nine of those years, but presumably there was room to add additional episodes) they arrive at the half-real, half-legendary destination of Vulture Peak, where, in a scene simultaneously mystical and comic, Xuánzàng receives the scriptures from the living Buddha.

Chapter 100, the last of all, quickly describes the return journey to the Táng Empire, and the aftermath in which each traveler receives a reward in the form of posts in the bureaucracy of the heavens. Sūn Wùkōng and Xuánzàng achieve Buddhahood, Wùjìng becomes the Golden Arhat, the dragon is made a Naga, and Bājiè, whose good deeds have always been tempered by his greed, is promoted to an altar cleanser (i.e. eater of excess offerings at altars).

Historical context [ ]

The classic story of the Journey to the West was based on real events. In real life, Xuanzang (born c. 602 - 664) was a monk at Jingtu Temple in late-Sui Dynasty and early-Tang Dynasty Chang'an. Motivated by the poor quality of Chinese translations of Buddhist scripture at the time, Xuanzang left Chang'an in 629, despite the border being closed at the time due to war with the Gokturks . Helped by sympathetic Buddhists, he traveled via Gansu and Qinghai to Kumul (Hami), thence following the Tian Mountains to Turfan. He then crossed what are today Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Afghanistan, into Gandhara, reaching India in 630. Xuanzang traveled throughout the Indian subcontinent for the next thirteen years, visiting important Buddhist pilgrimage sites and studying at the ancient university at Nalanda.

Xuanzang left India in 643 and arrived back in Chang'an in 646 to a warm reception by Emperor Taizong of Tang. He joined Da Ci'en Monastery (Monastery of Great Maternal Grace), where he led the building of the Big Wild Goose Pagoda in order to store the scriptures and icons he had brought back from India. He recorded his journey in the book Journey to the West in the Great Tang Dynasty . With the support of the Emperor, he established an institute at Yuhua Gong (Jade Luster Palace) monastery dedicated to translating into Chinese the scriptures he had brought back. His translation and commentary work established him as the founder of the Dharma character school of Buddhism. Xuanzang died on March 7, 664. The Xingjiao Monastery was established in 669 to house his ashes.

Popular stories of Xuánzàng's journey were in existence long before Journey to the West was written. In these versions, dating as far back as Southern Song, a monkey character was already a primary protagonist. Before the Yuan Dynasty and early Ming, elements of the Monkey story were already seen.

Relation to Dragon Ball [ ]

Main characters [ ], tripitaka or xuánzàng [ ].

Originally named Chén Yī (陳禕), Xuánzàng (玄奘), or Táng Sānzàng (唐三藏; meaning "Táng-dynasty monk" — Sānzàng /三藏 or "Three Baskets", referring to the Tripitaka, was a traditional honorific for a Buddhist monk) is the Buddhist monk who set out to India to retrieve the Buddhist scriptures for China. He is called Tripitaka in many English versions of the story. Although he is helpless when it comes to defending himself, the bodhisattva Guānyīn helps by finding him powerful disciples (Sun Wukong, Zhu Bajie, and Sha Wujing) who aid and protect him on his journey. In return, the disciples will receive enlightenment and forgiveness for their sins once the journey is done.

Along the way, the disciples help the Giancarlo by defeating various monsters. The fact that most of the monsters and demons are trying to obtain immortality by eating Sanzang's flesh, and are even attracted to him as he is depicted as quite handsome, provides much of the plot in the story (and in stage plays, it was a common choice for a woman to play the role as Sanzang which has lead to parodies of this tradition). Yet in spite of anyone's personal attractions to him, Sanzang remains celibate and is fully focused on his mission.

In some adaptions that mention it, his original incarnation from heaven is the Jin Chan Zi (金蝉子; lit. "Gold Cicada Child"). Originally, Jin Chan Zi was expelled from heaven for mainly ignoring Buddha's teachings (though how he was disobedient and/or banished varies a lot depending on the adaptation), with Chen Yi/Xuanzang being his 10th reincarnation.

Chen Yi before being a monk, was born to a mother named Yin Wenjiao with her husband Chen Guangrui being killed by a bandit named Liu Hong who was jealous of Chen's position of being recently appointed as a prefect. Wenjiao then put Xuanzang still as an infant on a wooden board to flow on a river out of fear that Liu Hong would find and kill him as well, where a monk managed to pick him up on the other end of the said river out of coincidence. Xuanzang at age 18 soon eventually reunited with his mother and father (whom the latter was saved by a dragon king of a river), and they brought Liu Hong to justice. Afterwards, he was then ordered by Emperor Taizong to bring the ancient Buddhist scriptures from India and also became sworn brothers with him.

Initially known to be reluctant and reserved, Xuanzang Sanzang was known to be devoted to his faith as a monk and a pacifist at heart, despite the fact that his kindness at times works against him (as demons that have disguised themselves as humans have attempted to make use of), yet his willingness to have Wukong and his cohorts spare some of their enemies earns him notable charisma that some have either tried to take further advantage of or have full-on relented from their ways for redemption.

Some adaptations have played with his level of fearfulness and naivety, and others instead (such as the 1996 and 2002 adaptations) portray him as more merciful and wise compared to his initial portrayals (and other adaptations may also give him combat skills to put him on an even floor with his disciples while still ensuring he is not able to inflict too much harm to his foes). Even then, Sanzang has remained true to his mission and had never once considered giving up. One other notable trait is his ability to sit perfectly still for up to 2 or 3 months; a skill he is most proud of from his days of meditation.

In Japanese on'yomi, his Buddhist name is rendered as Genjō . This title being Tō Sanzō or altogether with Xuanzang Sanzang as Genjō Sanzō . And his title of Sanzang Fashi (三藏法師, "Three Baskets Bonze") is romanized as Sanzō Hōshi . His original incarnation from heaven, Jin Chan Zi, is romanized as Konzen Dōji (金蝉 童子) in media such as the Japanese adaptation, Gensōmaden Saiyūki .

Monkey King or Sūn Wùkōng [ ]

Sūn Wùkōng (孫悟空) is the name given to this character by his teacher, Patriarch Subhuti, and means "Monkey Awakened to Emptiness". He is called Sūn Xíngzhě (孫行者, Son Gyōja ) by Xuánzàng (with most adaptations still having him named as "Wukong" by Xuánzàng). While he is commonly known as Monkey King in pop culture, with one of his more egotistical titles being the Handsome Monkey King (美猴王, Měi Hóuwáng/Bikō'ō ). He is by far, the novel's most iconic character.

He was born out of a rock that had been dormant for ages on Flower Fruit Mountain ( Huāguǒshān / Kakazan ) that was inhabited/weathered by the sun and moon until a monkey sprang forth. He first distinguished himself among other fellow monkeys by bravely entering the Cave of Water Curtains ( Shuǐliándòng/Suirendou ); for this feat, his monkey tribe gave him the aforementioned title of "Handsome Monkey King". He soon wanted to go on a quest to study the secrets to immortality, and eventually encountered and studied under Subhuti to learn magic and other various skills (but in trade, was told to never tell anyone who taught him such abilities). Subhuti was also the one to give Wukong his current name, with the "Sun" surname being in ode to his nature as a monkey.

Later, through some misfits involving writing his and other fellow monkeys' names out of the Book of Death in Hell (when it was Wukong's time to die), claiming the East Sea Dragon King's sea needle for himself, he initially was setup for punishment from Heaven yet was given a post as a stable boy. But once he learned of his actual ranking, he ditched the position and back at his mountain renamed himself as "Great Sage Equal to Heaven". Trying to appease him further, they set him to watch over the heavenly peach garden, only for him to be infuriated that he was not invited to a grand banquet and during the preparations with using his magic to everyone working to sleep, stole much of the food and, even resorted to devouring of the peaches of immortality and three jars of immortality pills meant for the Jade Emperor.

Wukong after bringing the stolen food to his monkeys to host his own party back on the mountain, heaven decided enough was enough and it escalated into a full-on war. The monkey defeated an army of 100,000 celestial soldiers, led by the Four Heavenly Kings, Erlang Shen, and Nezha. Eventually, he was then captured. Yet even when Wukong underwent execution after execution, his body from the prior heavenly foods consumed just would not allow him to be harmed in anyway (and eventually even dozed off to sleep in boredom). He was then sealed inside a special furnace as a last resort with the intent of turning him into an elixir, but he broke free and nearly trashed much of the heavenly palace in retaliation; the Jade Emperor appealed to Buddha, who after beating Wukong's attempt at a competition, subdued and trapped the monkey under a mountain for five centuries to repent, with Guanyin occasionally checking in. He was only saved when Xuanzang Sanzang came by him on his pilgrimage and accepted him as a disciple.

His primary weapon is the Rúyì Jīngū Bàng/Nyoi Kinko Bō (如意金箍棒; lit. "Compliant Gold-Rimmed Pole"), which he can shrink down to the size of a needle and keep behind his ear, as well as expand it to gigantic proportions (hence the "compliant" part of the name; some adaptations show the staff to act as if it was alive). The staff, originally a pillar supporting the undersea palace of the East Sea Dragon King, weighs 13,500 kilograms, which Wukong pulled out of its support and swung with ease as it was first offered to Wukong to see if it was a weapon he could wield without breaking like others the monkey had attempted to wield. The Dragon King, not wanting him to cause any trouble, also gave him a suit of golden armor, headpiece and boots

These gifts, combined with his aformentioned devouring of the immortality peaches and immortality pills (giving his already rock-solid-body even more invulnerability), plus his ordeal in an eight-trigram furnace (which gave him the Gold Gaze Fire Eyes to see through evil's disguises but giving his eyes a weakness to smoke), makes Wukong the strongest member by far of the pilgrimage. Besides these abilities, he can also pull hairs from his body and blow on them with magic to transform them into whatever he wishes (usually clones of himself to gain a numerical advantage in battle).

Although he has mastered seventy-two methods of transformations, it does not mean that he is restricted to seventy-two different forms. He can also do a Jīndǒuyún/Kinto'un (筋斗雲; lit. "Somersault Cloud"), enabling him to travel vast distances in a single leap, or ride on a cloud to cover the same amount of distance with flight-based speed (at 108,000 li or 54,000 km). Wukong uses his talents to fight demons and play pranks. However, his behavior is checked by a band placed around his head by Guanyin, which cannot be removed by Wukong himself until the journey's end. Xuanzang Sanzang can tighten this band by chanting the Tightening Hooplet Spell (taught to him by Guanyin) whenever he needs to chastise him. In spite of continuous disagreements with his master and fellow disciples causing Wukong to ditch the party back to his home of Flower Fruit Mountain, he would eventually be able to be convinced and/or reminded to come back after some soul-searching, which proves his developing devotion.

Wukong's childlike playfulness is a huge contrast to his cunning mind. This, coupled with his acrobatic skills, makes him a likeable hero, though not necessarily a good role model given his abrasiveness and initial sociopathic tendencies (even resorting to killing before being tamed by his master throughout the journey). His antics present a lighter side in what proposes to be a long and dangerous trip into the unknown, and overall develops a sense of endearment to his master and fellow disciples in his heart throughout the journey. Some adaptations also make him borderline prone to breaking the fourth wall or making references to other media as a testament to his character depending on the era (such as with Stephen Chow's adaptations of him). Even then, Wukong makes it clear that he is unable to let injustice slide and often takes matters into his own hands (or plays around with the entire scenario) to have a good outcome for any rough situation, even if rather impulsively driven at best and at times being prone to anger. His other main weakness he acknowledges and tries to work-around is his lack of underwater combat ability, which is covered by both Bajie and Wujing.

In Japanese on'yomi, Sun Wukong is romanized more famously as Son Gokū , especially with the popularity of Dragon Ball . His title of Qitian Dasheng (齊天大聖; lit. "Equaling Heaven Great Sage") is known as the Seiten Taisei in Japanese and is mainly to appease his ego (though it does provide a form of respect as the lesser gods would prove, and his actual prior havoc in heaven also can back such a title up). However, his title of "Heavenly Stable Boy" due to its low rank is one way to easily rile him up.

Zhū Bājiè [ ]

Zhū Bājiè (豬八戒; lit. "Pig of the Eight Precepts") is also known as Zhū Wùnéng (豬悟能; lit. "Pig Awakened to Ability") and given the name Pigsy , Piggy or Pig in English.

Once an immortal who was the Tiānpéng Yuánshuǎi (天蓬元帥; lit. "Heaven Canopy Marshall") of 100,000 soldiers of the Milky Way, during a celebration of gods, he drank too much and attempted to flirt with Cháng'é, the beautiful moon goddess, resulting in his banishment into the mortal world. He was supposed to be reborn as a human but ended up in the womb of a sow due to an error at the Reincarnation Wheel, which turned him into a half-man half-pig monster. Staying within Yúnzhandòng ("Cloud Pathway Cave"), he was commissioned by Guanyin to accompany Xuanzang to India and given the new name Zhu Wuneng.

However, Wuneng's desire for women led him to Gao Village, where he posed as a normal being and took a wife and was noted to "work as hard as he ate". Later, when the villagers discovered that he was a monster, Wuneng hid the girl away. At this point, Xuanzang and Wukong arrived at Gao Village and helped subdue him. Renamed Zhu Bajie by Xuanzang, he consequently joined the pilgrimage to the West.

His weapon of choice is the jiǔchǐdīngpá ("nine-tooth nail rake"), mainly given to him as a status symbol by the Jade Emperor when first promoted to the rank of field marshall. He is also capable of thirty-six transformations (as compared to Wukong's seventy-two), and can also travel on clouds, but not as fast as Wukong. However, Bajie is noted for his fighting skills in the water due to his naval troop experience, which he used to combat Sha Wujing, who later joined them on the journey. He is the second strongest member of the team.

He is often noted to be quite gluttonous, perverted and a bit cowardly (mainly from his demotion that occurred with his reincarnation having a clear effects on reducing his power and confidence), which often has him at odds with Wukong's more abrasive and playful attitude. But nonetheless he is loyal to his friends deep down and is trusting of his master and vice versa, as well as often getting along with Wujing. Many adaptations of the novel tend to paint him in a light for the sake of comic relief, while also making him act as a positive force that differs from Wukong's antics in spite of his jealousy towards the monkey.

Even with his perversions in mind causing him to drool, Bajie makes it clear he can relate to others and understands the concepts of love (which some adaptations have made him a bit of a cultured poet or a sucker for sob-stories). While he may complain about his own misfortunes often in regards to his laziness, Bajie in a majority of fluctuating situations does not act as anxious as Wukong and Wujing as per his days as a field marshall while also learning to have fun alongside Wukong's antics at times.

In Japanese on'yomi, Zhu Bajie's current name is known as Cho Hakkai , and his original name before being renamed by Sanzang in Japanese is Cho Gonō . His original incarnation's title, Tianpeng Yuanshui , is known fully as Tenpō Gensui in Japanese as well (via Gensōmaden Saiyūki ).

Shā Wùjìng [ ]

Shā Wùjìng (沙悟凈; lit. "Sand Awakened to Purity"), also named Shā Sēng (沙僧) in Mandarin Chinese or " Ol' Sandy ". He is also given the name Friar Sand or Sandy in English, with the former name being one of his other names, Shā Héshàng (沙和尚; "Sand Preceptor"). He was once the Juǎnlián Dàjiàng (捲簾大将; lit. "Rolling Curtain General"), who stood in attendance by the imperial chariot in the Hall of Miraculous Mist. He was exiled to the mortal world and made to look like a monster because he accidentally smashed a crystal/jade goblet belonging to the Heavenly Queen Mother during the Peach Banquet. The now-hideous immortal took up residence in the Flowing Sands River, terrorizing the surrounding villages and travelers trying to cross it. However, he was subdued by Sun Wukong and Zhu Bajie when the Sanzang party came across him. They consequently took him in to be a part of the pilgrimage to the West.

Sha Wujing's weapon is the Yuèyáchǎn ("Moon Fang Spade" or "Monk's Spade"). Aside from that, he knows eighteen transformations and is highly effective in water combat. He is about as strong as Bajie, and is much stronger than Wukong in water. However, Bajie can beat Wujing in a test of endurance, and Wukong can beat him out of water.

Wujìng is known to be the most obedient, logical, and polite of the three disciples, and always takes care of his master, seldom engaging in the bickerings of his fellow-disciples. Ever reliable, he carries the luggage for the travelers and often prioritizes safety of others around him. Perhaps this is why he is sometimes seen as a minor character; the lack of any particular perks confers the lack of distinguishing and/or redeeming characteristics aside from being astute and having some moments of his own spotlight to cover the group's back. Though the 1996 adaptation is famous for making him rather unintelligent and/or stating the obvious (which was hinted even when acting as a general and the reasoning behind his accident), but makes up for it with being head-strong, honest and hyper-focused on important tasks to a fault.

Wujiìng eventually becomes an arhat at the end of the journey, giving him a higher level of exaltation than Bajie, who is relegated to cleaning every altar at every Buddhist temple for eternity via consuming the leftovers (which he is rather fond of), but is still lower spiritually than Wukong or Xuanzang who are granted Buddhahood.

In Japanese on'yomi, Sha Wujing is romanized as Sha Gojō , with his original incarnation's name/title romanized as Kenren Taishō in Gensōmaden Saiyūki . In Japanese, the character for "jing/jō" is written differently in Japanese due to conflicting writing systems, with 淨 being the older form closer to Chinese, and 浄 being the current character used.

List of Demons [ ]

There are many demons in the story. Examples are listed below:

- Black-Bear-Demon (pinyin: Hēixióngguài )

- Yellow Wind Demon (Huángfēngguài)

- Zhen Yuan Holy Man; he is not a demon, but an immortal, who got annoyed by the disciples who stole his precious immortal-fruits (Ginseng Fruits, 人参果).

- White-Bone-Demon (pinyin: Báigǔjīng )

- Yellow Robe Demon (pinyin: Huángpáoguài )

- Gold-Horn and Silver-Horn (pinyin: Jīnjiǎo and Yínjiǎo )

- Crimson Boy a.k.a. Holy Baby King (pinyin: Hónghái'ér ; Japanese: Kōgaiji )

- Tiger Power, Deer Power, and Goat (or Antelope) Power Great Hermits

- Black River Dragon Demon (Hēi Shǔi Hé Yuan Lóng Gài)

- Carp Demon (Li Yu Jīng)

- Green-Ox-Demon (pinyin: Qīngniújīng )

- Scorpion-Demon (pinyin: Xiēzijīng )

- Six Ear Macaque (a.k.a Fake Sun Wukong, Lìuěrmíhóu )

- Ox/Bull Demon King (pinyin: Niúmówáng ; Japanese: Gyūmaō ): The inspiration for the Ox King , who also shares the same name in the Asian scripts/dubs as the original Ox-Demon-King.

- Demon Woman (Luo Cha Nǚ)

- Jade-Faced Princess (pinyin: Yùmiàn Gōngzhǔ ; Japanese: Gyokumen Kōshū )

- Boa Demon ( Hóng Shé Jīng )

- Nine-Headed Bird Demon (Jiǔ Tou Fu Ma)

- Seven-Spider-Demons (pinyin: Zhīzhū-jīng )

- Hundred-Eyed Taoist (Bǎi Yan Mo Jun)

- Green Lion Demon (pinyin: Qīngshījīng )

- White-Elephant-Demon (pinyin: Báixiàngjīng )

- Falcon Demon (Sun Jīng)

- Biqiu Country Minister a.k.a Deer Demon

- Gold-Nosed, White Mouse Demon (Lao Shu Jīng)

- Dream-Demon

Notable English-language translations [ ]

- Monkey: A Folk-Tale of China (1942), an abridged translation by Arthur Waley. For many years, the best translation available in English; it only translates thirty out of the hundred chapters. (Penguin reprint ISBN 0-14-044111-5 )

- Journey to the West , a complete translation by W.J.F. Jenner published by the Foreign Languages Press in Beijing 1955 (three volumes; 1982/1984 edition: ISBN 0-8351-1003-6 , ISBN 0-8351-1193-8 , ISBN 0-8351-1364-7 )

- The Journey to the West (1977–1983), a complete translation in four volumes by Anthony C. Yu. University of Chicago Press: HC ISBN 0-226-97145-7 , ISBN 0-226-97146-5 , ISBN 0-226-97147-3 , ISBN 0-226-97148-1 ; PB ISBN 0-226-97150-3 , ISBN 0-226-97151-1 ; ISBN 0-226-97153-8 ; ISBN 0-226-97154-6 .

Media adaptations [ ]

- Journey to the West: The Musical : A stage musical which received its world premiere at the New York Musical Theatre Festival on September 25, 2006.

- Monkey: Journey to the West : A stage musical version created by Chen Shi-zheng, Damon Albarn (frontman of British rock band Blur) and Jamie Hewlett, the latter two better known as creators of the Gorillaz musical project. It premiered as part of the 2007 Manchester International Festival at the Palace Theatre on June 28.

- The Monkey King : A production by the Children's Theater Company in Minneapolis, MN in 2005.

- A Chinese Odyssey by Stephen Chow.

- A Chinese Tall Story : 2005 live action movie starring Nicholas Tse as Xuánzàng.

- Heavenly Legend : A 1998 film by Tai Seng Entertainment starring Kung Fu kid Sik Siu Loong is partially based on this legend.

- Monkey Goes West : The Shaw Brothers' 1966 Hong Kong film (Cantonese: Sau yau gei ). Also known as "Monkey with 72 Magic"

- The Forbidden Kingdom : 2008 live action movie starring Jackie Chan and Jet Li which is said to be based on the Legend of the Monkey King, the same legend as the TV show Monkey. Towards the end, Li's character is revealed to be the Monkey King of the legend. [1]

Live-action television [ ]

- Monkey (1978–1980): A well-known 1970s Japanese television series based on Journey to the West translated into English by the BBC.

- Journey to the West (1986): A TV series produced by CCTV.

- Journey to the West (1996): A popular series produced by Hong Kong studio TVB, starring Dicky Cheung.

- Journey to the West II (1998): The sequel to TVB's Journey to the West series, starring Benny Chan.

- The Monkey King (2001): Sci Fi Channel's TV adaptation of this legend, also called The Lost Empire .

- The Monkey King: Quest for the Sutra (2002): A loose adaptation starring Dicky Cheung, who also portrayed Sun Wukong in the 1996 TVB series.

- Saiyūki (2006): A Japanese television series starring the SMAP star Shingo Katori.

Comics, manga and anime [ ]

- Alakazam the Great : One of the first anime films produced by Toei Animation , a retelling of first part of the story based on the characters designed by Osamu Tezuka.

- Coincidentally, both the version of Wukong/Goku and Wujing/Gojo share traits of the original Bajie/Hakkai; the former shares Bajie's hunger (akin to Dragon Ball' s version of Wukong/Goku), while the latter shares Bajie's lust/perversions for women. Both of them also often argue back-to-back, akin to Wukong and Bajie's dynamics in the original source material.

- Havoc in Heaven (also known as Uproar in Heaven ): Original animation from China.

- Iyashite Agerun Saiyūki : A 2007 adult anime [1]

- Monkey Magic : An animated retelling of the legend.

- Monkey Typhoon : A manga and anime series based on the Journey to the West saga, following a futuristic steampunk-retelling of the legend.

- Starzinger : An animated science fiction version of the story.

- The Monkey King : A gruesome manga inspired by the tale.

Works referencing Journey to the West [ ]

- American Born Chinese : An American graphic novel by Gene Yang. Nominated for the National Book Award (2006).

- Doraemon : A special tells the story of Journey to The West , casting the Doraemon characters as the characters of the legend.

- Dragon Ball : Japanese manga and anime series loosely based on Journey to the West .

- Eyeshield 21 : Three of the players for the Shinryuji Nagas are referred to as the Saiyuki Trio based upon their appearances and personalities.

- InuYasha : The characters meet descendants of three of the main characters of the Journey of the West , led by Cho Kyuukai (a boar demon ), in one episode. Also, the main character Kagome Higurashi says a few lines about the whole book and story and explains it to the others who live in Feudal Japan, ergo have not heard about the Journey to the West .

- Kaleido Star : The cast performs Saiyuki on stage a few times in the beginning of the second half of the series.

- Love Hina : The characters put on a play based on the story in anime episode 16.

- Naruto : A character named Temari is based on Princess Iron Fan from the legend. Enma is a summoned monkey who bears resemblance to Sun Wukong. He has the ability to transform into a staff similar to the rúyì-jīngū-bàng , which can alter its size at will. Also, one of the Tailed Beasts (also known as Bijū ) is named Son Gokū with the exact same kanji for both the Monkey King and the Earthling-raised Saiyan, sporting horns which resemble the diadem worn by the original Wukong/Goku.

- Ninja Sentai Kakuranger : The 1994 Super Sentai series, where four of the five rangers are inspired by the main characters of Journey to the West

- GoGo Sentai Boukenger : The 2006 Super Sentai series, where its final episode involved the Rúyì-jīngū-bàng

- Juken Sentai Gekiranger : The 2007 Super Sentai series, where one of its villain's fighting style is homage to Sun Wukong.

- Patalliro Saiyuki : A shōnen-ai series in both anime and manga formats with the Patalliro cast playing out the Zaiyuji storyline with a yaoi twist.

- Ranma 1/2 : Pastiches of the characters appear throughout the manga and movies.

- Read or Die (OVA) : One of the villains is a clone of Xuanzang, who seems to have the powers of Sun Wukong and Xuanzang.

- Sakura Wars : The Imperial Flower Troupe Performs the play of Journey to the West . Ironically, Mayumi Tanaka , who voices Krillin and Yajirobe in the Dragon Ball franchise, voices the monkey king Son Goku in the play.

- Shinzo : An anime loosely based on Journey to the West .

- XIN : An American comic mini-series produced by Anarchy Studio.

- Pokémon : Infernape, a Fire/Fighting Pokémon, has a design based on motifs related to Sun Wukong and Emboar, another Fire/Fighting Pokémon, has a design based on motifs similar to Zhu Bajie.

- The God of Highschool : A Korean web-toon that barrows a lot of the elements from every mythology notable, with few of the main cast based on characters from the novel. The main character, Jin Mo-Ri , being based off the Monkey King as well as Dragon Ball's Son Goku.

- Yuu Yuu Ki : A video game for the Famicom Disk System, based directly on the story.

- Journey to the West : An unlicensed Famicom game by Taiwanese developer TXC Corp, 1994. [2]

- Pokémon Diamond and Pearl : A video game and multi series in which the Pokémon creatures Chimchar, Monferno, and mainly Infernape are based on Sūn Wùkōng.

- Coincidentally, the portrayal of Zhu Bajie/Cho Hakkai is voiced by Naoki Tatsuta , who also voices Oolong with Bajie being his inspiration.

- Fuun Gokuu Ninden : An action game for the PlayStation. The characters of the game are based on the characters of Journey to the West . [3]

- Saiyu Gouma Roku : A 1988 arcade game by Technos, based in the original story and characters. The North American version is named "China Gate". [4]

- SonSon : A video game and character of the same name created by Capcom whose title character is a caricature of Sun Wukong (and would be read as "SunSun" in pinyin). The granddaughter of SonSon (also named SonSon, or SonSon III) appears in Marvel vs. Capcom 2 as a playable character.

- Westward Journey : A massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG).

- Whomp 'Em : NES game whose Japanese version is based on the story (the American version features an Indian boy instead of Wukong). Although a marketing failure, it is also a cult classic.

- Likewise, the two other MOBA games, Smite and Heroes of the Werwerth , also feature the original Sun Wukong as a playable character, with the former having removed him from the game for a visual rework to resemble the original figure, and the latter being simply known as "Monkey King" and possessing a skin that's a close reference to Dragon Ball in general (almost resembling the Dragon Ball Wukong/Goku's Super Saiyan 4 form). Smite also has other characters pertaining to the legend or similar ones that tie into Journey into the West in general, such as the East Sea Dragon King and Nezha/Nata (the former also received a similar rework). Defense of the Ancients 2 has also recently revealed their own version of the Monkey King as well.

- More so however, Masako Nozawa , the Japanese voice actress of the Dragon Ball Wukong/Goku, also voices the League of Legends Wukong in the Japanese dub as a direct allusion. Meanwhile, Sean Schemmel has voiced the reworked Wukong in Smite as another allusion.

Brazen Courage Gohan (Kid) card from Dokkan Battle

Courage to the Max! Goku card from Dokkan Battle

- Asura's Wrath (アスラズ ラース, Asurazu Rāsu ) : A video game developed by CyberConnect2 and published by Capcom. The game is playable on PlayStation 3, Xbox 360, Xbox One via 360 backwards compatibility, and the PlayStation 4 and PC via PlayStation Now. The game follows the title character, the demigod Asura as he seeks revenge on the pantheon of other demigods who betrayed him.

- In Dragon Ball Z: Dokkan Battle , there are two cards based upon the Journey to the West inspired outfits worn by Goku and Gohan . Goku's is called Courage to the Max! Goku card and Gohan's is Brazen Courage Gohan (Kid) card. Both cards are Legendary Rare cards that feature Super Attacks featuring Goku and Gohan wielding their respective Power Poles (Gohan's Power Pole design features a more Journey to the West -style design rather than the Dragon Ball style design of Goku's Power Pole). Both characters ride a Flying Nimbus to fit the Sun Wukong motif.

Female Future Warrior wearing the Saiyuki Outfit in Dragon Ball: Xenoverse

- In Dragon Ball Xenoverse , there is an unlockable Saiyuki outfit which is described as a Journey to the West-style outfit, which can be unlocked by making a wish of " I want to dress up! " to Shenron. It is based on the Journey to the West inspired outfit worn by Gohan on Manga cover page for DBZ: 13 " Son Gohan, the Inconsolable " and Gohan also wears the same outfit in Detekoi Tobikiri ZENKAI Power! . There is also an NPC Shapeshifter Nema who also wears the costume as part of one of her transformations, though she has no idea as to who the transformation is supposed to be.

Goku wearing his Journey to the West Costume from Dragon Ball Xenoverse 2

- After the 1.09.00 Update, the Future Warrior can purchase Gifts which are special costumes that they can give to Instructors which can then be worn via Partner Customization. Gift (Goku) unlocks Goku's Journey to the West Costume for Goku to wear (it comes complete with Hood though the Hood will be removed when Goku transforms into any of his available Super Saiyan forms). Gift (Gohan (Kid)) unlocks his Saiyuki Costume ( Journey to the West Costume) from DBZ : 13 " Son Gohan, the Inconsolable " and Detekoi Tobikiri ZENKAI Power! (it also comes complete with Hood as well). Both Gifts can be purchased at the TP Medal Shop.

References [ ]

- ↑ Journey to the West . Unlicensed NES Guide .

- ↑ Fuun Gokuu Ninden (The God of Monkey) . Extreme-Gamers .

- ↑ China Gate . Coin-Op Express .

External links [ ]

- Inspirations of Dragon Ball at fullpowerdbz.com

- Monkey - Great Sage equal of Heaven - fansite

- Journey to the West - Freeware complete English text version in PDF format (2.56MB). From Chine Informations

- Journey to the West - Comprehensive and detailed website with in-depth information about Journey to the West.

- Story of Sun Wukong and the beginning of Journey to the West with manhua

- Complete novel in Simplified Characters (utf-16 encoding).

- Solarguard Monkey Plot summary (one paragraph for each of one hundred in novel) plus summary of book on historical Xuanzang.

- Summary of most chapters of Journey to the West and more, illustrated by various paintings from Summer Palace

- 2 List of Power Levels

Akira Toriyama Based 'Dragon Ball' on This 400-Year-Old Story

Your changes have been saved

Email is sent

Email has already been sent

Please verify your email address.

You’ve reached your account maximum for followed topics.

The Big Picture

- Dragon Ball draws heavy inspiration from the classic Chinese novel, Journey to the West , which remains influential even after centuries.

- Son Goku is based on Sun Wukong, the powerful Monkey King from Journey to the West , who accompanies the monk Tang Sanzang on his journey.

- Other characters in Dragon Ball , such as Bulma, Oolong, Yamcha, and the Ox-King, also have parallels to characters from Journey to the West .

Son Goku of Dragon Ball isn't just Earth's greatest protector; he's also one of the most recognizable characters in all fiction. For both Western and Eastern audiences, his unruly spiky hair, bright orange gi, and positive-yet-diligent personality make him one of the most beloved figures in media. Goku has become a symbol in his own right, representing the power of determination and the strength of a purely good heart, but the source of inspiration that led to his creation is likewise an incomprehensibly entertaining and captivating being, known as Sun Wukong .

As with many great fictional works, the origins of Dragon Ball can be traced back to mythical legends and classic folk tales that have endured the wear of time. Dragon Ball 's visionary creator, Akira Toriyama, to whom the world is bidding a sorrowful farewell , based a significant portion of his story, character designs, and thematic elements on the classic Chinese novel, Journey to the West. Despite being written over 400 years ago, Journey to the West remains prevalent and impactful in modern writing, with its influence apparent in almost every corner of Toriyama's hit series, with plenty of parallels and allusions that tie the two beloved stories together, despite the four centuries of time that stand between them.

Dragon Ball (1986)

Son Gokû, a fighter with a monkey tail, goes on a quest with an assortment of odd characters in search of the Dragon Balls, a set of crystals that can give its bearer anything they desire.

What Is 'Journey to the West' About?

Akira Toriyama took heavy inspiration from the classic Chinese story, Journey to the West . The novel, considered one of the most influential and significant pieces of literature from China, was first published in the 16th century, but its impact is felt even centuries later. Journey to the West is based on the pilgrimage of a Buddhist monk named Xuanzang who traversed across the land to retrieve sacred texts, after much trial and tribulation. The novelization of this journey follows a monk called Tang Sanzang, likewise in search for sacred Buddhist texts, but contains fantastic and mythical elements that made the adventure an enduring literary piece.

To aid in his journey, Tang Sanzang is accompanied by magical characters such as Sun Wukong, Zhu Bhajie, and Sha Wujing, each distinct in ability, appearance, and personality. On their quest, the heroes must overcome fearful monsters and traverse dangerous landscapes as they search for the sacred texts. Though the story was written with allegories and metaphors connected to China during that time period, it nonetheless endures in popularity because of its universal themes about human determination and the captivating fantasy elements that would serve as inspiration for countless works written generations after . Journey to the West itself would spawn several modern adaptations that recounted the story of Tang Sanzag, including several films and television series. But despite not being a direct adaptation of the original story, Dragon Ball is a strong contender for the best successor of the legacy of this Chinese novel.

Son Goku Takes Inspiration From the Legendary Monkey King, Sun Wukong

The foremost allusion to Journey to the West in Dragon Ball is apparent in the latter's main character: Son Goku . Goku is based on Sun Wukong, also known as the Monkey King , a powerful being that accompanied the monk Tang Sanzang on his journey for the sacred texts. Sun Wukong is one of the most powerful beings in existence, a magical and immortal monkey with dozens of fantastic abilities and strength that surpasses practically all others. Like Wukong, Goku is powerful and energetic, bearing an unbelievable amount of strength and talent unmatched by anyone else in the series. If Goku were just a strong person with a tail, that would already be an excellent reference to Wukong, but Toriyama solidified the inspiration even further with Goku's transformation into the Great Ape, punctuating the similarities between him and the Monkey King.

Sun Wukong's inspiration doesn't end there, as several magical artifacts from the old Chinese story were also adapted in Dragon Ball . Like Goku's Power Pole, the Monkey King possessed a staff capable of dramatically changing its size at the user's command. Both monkey-related characters also rode magical flying clouds, as Goku's Flying Nimbus was based on Wukong's similar cloud and ability. And don't let the fact that Goku is an alien separate his birth from Wukong either. Goku's space pod that he was sent to Earth in as a baby bears a surprisingly stone-like appearance as a direct reference to Wukong's own birth, as he came to life after bursting from a magical rock.

'Dragon Ball's Supporting Characters Are Also Inspired by ‘Journey to the West’

The connections to Journey to the West are not limited to Goku alone, as many of the major players in the earliest arcs of Dragon Ball are parallels to characters from the Chinese novel. Since Sun Wukong is the breakout character from the tale, some of these allusions may be less apparent at first glance, but the inspiration is there nonetheless. Bulma serves as the proxy for Tang Sanzang, despite being the furthest image of a Buddhist monk that one can possibly become. However, Bulma's search for the legendary Dragon Balls is, at its core, taken from Tang Sanzang's retrieval of the sacred Buddhist texts .

Dragon Ball's Oolong is based on Zhu Bajie, a shape-shifting pig spirit that was the second of Tang Sanzang's disciples after Sun Wukong. Both characters are also known for their gluttonous and lustful personalities. The third of Tang Sanzang's allies was Sha Wujing, a man-turned-demon who is later redeemed when he accompanies the monk on his travels. In Dragon Ball , this role is taken by Yamcha, who was similarly first depicted as a villain, before quickly becoming one of Goku and Bulma's close allies. In addition to their narrative similarities, Tang Sanzang and Yamcha also had strong ties to the desert and martial arts — which can be easy to forget because of how far Dragon Ball has evolved since the days when Yamcha was able to best Goku in a fight . The Ox-King from Dragon Ball shares the same exact name as a character from Journey to the West , as well as a similar home to his namesake. Both Ox-Kings resided on flaming mountains, a unique location that solidifies the relation between the two.

'Dragon Ball Z's Android Family Tree Explained

The Androids are some of the fiercest opponents the Z-Fighters have ever faced, but what's the story behind these robotic warriors?

Akira Toriyama Moved Further Away From 'Journey to the West' With 'Dragon Ball Z'

Toriyama's writing in early Dragon Ball didn't just take design choices and naming conventions from Journey to the West , but also took inspiration from its narrative structure and thematic elements. Each character modernizes the role first established by their source material from several centuries earlier. For instance, viewers more familiar with Dragon Ball Z and further sequels may not even know that Bulma was actually the active character at the start of the series. It's her search for the Dragon Balls that sets the story in motion , and Goku is recruited to help her accomplish that goal. In Journey to the West , Wukong is depicted as supernaturally powerful, even compared to his staunchest allies and fiercest rivals, much in the same way that Goku is established as a formidable force, even as a child. They could both be considered "over-powered," but that's exactly the point. Oolong's selfish vices and Yamcha's face-turn are likewise the necessary foils to Goku's pure-of-heart personality and Bulma's determination, exactly like the characters they were based on.

As Dragon Ball progressed (even just in later arcs, not even accounting for DBZ and beyond ), the story evolved beyond its original source of inspiration. The narrative shifts away from the search for the Dragon Balls and characters rise and fall in relevance as the series evolves into one of the most important pioneers of the shōnen battle anime genre , becoming the predecessor to several generations of anime , much in the same way that Journey of the West did for Toriyama.

Dragon Ball is available to stream on Crunchyroll in the U.S.

Watch on Crunchyroll

- TV Features

- Dragon Ball

- Celebrities

- Photography

- Link in bio

Journey To The West: The Chinese Inspiration Behind Dragon Ball

A monkey with superhuman strength and supernatural combat skills always carries with him a sacred scepter and has the ability to walk on clouds. He is also able to change his appearance. His only weakness? His tail.

Sounds familiar?

Although this might sound like the description of a very popular cartoon character, this is the description of an ancient Chinese legend, thousands of years old, the archetype of a hero that has been adapted and adopted by many cultures and that has served as the inspiration for novels, plays, manga, anime, and video games: Sun Wukong.

Journey to the West: From Sun Wukong to Son Goku

Sun Wukong is the main character in the Chinese literature classic, Journey to the West, which follows the adventures and hardships faced by buddhist monk Xuanzang in his long journey to India, a pilgrimage made in search for illumination and to recover the sutras (sacred texts in the buddhist tradition) to bring them back to China. Throughout his journey, Xuanzang is provided with three protectors: a demon who has natural abilities in water combat (Sha Sheng), a pig (Zho Wuneng), and Sun Wukong, a monkey.

The original version of this anonymous story dates back to the 16th century and has a hundred chapters, with the first seven exploring Sun Wukong’s background, when he was known as the King Monkey. His origin is supernatural, and the story explains how this monkey learns from his master; his abilities go from shape-shifting to becoming immortal.

Along his journey, Sun Wukong acquires a scepter that gives him the ability to shape-shift as well as other abilities, like controlling the fur on his body and transforming into objects or living beings, and walking on clouds.

After facing several Chinese gods and defeating them, The Monkey King challenged the Jade Emperor, the ruler of the heavens and maximum authority in the Chinese pantheon. For this, he was locked up by Buddha himself for a period of 500 years, until he offers himself as Xuanzang’s servant in exchange for his freedom.

It is no coincidence that Goku –the main character in Dragon Ball, a manga created by Akira Toriyama, one of the industry’s living legends– and Sun Wukong share so many common traits. Both stories include some iconic symbols and an unstoppable search for an object that gives meaning to the journey, as well as super human abilities and a kinship with monkeys.

However, as the manga and the TV series became more and more popular, the story of Goku diverted from the original, and little by little, it strayed from the story in Journey To The West; but in order to understand the origin of the sayajin, you definitely need to go back to Sun Wukong.

Do you know the true story of an iconic popular character? Click here to send a 400-word article and for the chance to appear in our website!

For more articles about popular culture and cool stories click here: The Best Most Irreverent Thanksgiving Cartoon Episodes To Laugh Your Ass Off 15 Feminist Lessons You Can Learn From The Powerpuff Girls Why I Relate To SpongeBob More Now Than In My Childhood

Isabel Carrasco

History buff, crafts maniac, and makeup lover!

© Cultura Colectiva 2023

- Código de Ética

- Aviso de Privacidad

- FUNimation subtitles

- FUNimation/Ocean Group dub

- FUNimation Kai dub

- Harmony Gold dub

Journey to the West

From dragon ball encyclopedia, the ''dragon ball'' wiki.

Journey to the West ( 西遊記 , Saiyūki ) is one of the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature. Originally published anonymously in the 1590s during the Ming Dynasty, it has been ascribed to the scholar Wú Chéng'ēn since the 20th century even though no direct evidence of its authorship survives.

The tale is also often known simply as Monkey . This was one title used for a popular, abridged translation by Arthur Waley . The Waley translation has also been published as Adventures of the Monkey God , Monkey: [A] Folk Novel of China , and The Adventures of Monkey .

The novel is a fictionalized account of the legends around the Buddhist monk Xuánzàng's pilgrimage to India during the Táng dynasty in order to obtain Buddhist religious texts called sutras. The Bodhisattva Kuan Yin|Guānyīn, on instruction from the Buddha, gives this task to the monk and his three protectors in the form of disciples – namely Sūn Wùkōng, Zhū Bājiè and Shā Wùjìng – together with a dragon prince who acts as Xuánzàng's horse mount. These four characters have agreed to help Xuánzàng as an atonement for past sins.

Some scholars propose that the book satirizes the effete Chinese government at the time. Journey to the West has a strong background in Chinese folk religion, Chinese mythology, and value systems; the pantheon of Taoist deities and Buddhist bodhisattvas is still reflective of Chinese folk religious beliefs today.

Part of the novel's enduring popularity comes from the fact that it works on multiple levels: it is a first-rate adventure story, a dispenser of spiritual insight, and an extended allegory in which the group of pilgrims journeying toward India stands for the individual journeying toward enlightenment.

- 2 Historical context

- 3.1 Tripitaka or Xuánzàng

- 3.2 Monkey King (Emperor of Monkeys) or Sūn Wùkōng

- 3.3 Zhū Bājiè

- 3.4 Shā Wùjìng

- 4 List of Demons

- 5 Notable English-language translations

- 6.3 Live action television

- 6.4.1 Works referencing Journey to the West

- 7 References

- 8 External links

The novel comprises 100 chapters. These can be divided into four very unequal parts. The first, which includes Chapter 1–7, is really a self-contained prequel to the main body of the story. It deals entirely with the earlier exploits of Sūn Wùkōng, a monkey born from a stone nourished by the Five Elements, who learns the art of the Tao, 72 polymorphic transformations, combat and secrets of immortality, and through guile and force makes a name for himself as the Qítiān Dàshèng , or "Great Sage Equal to Heaven". His powers grow to match the forces of all of the Eastern (Taoist) deities, and the prologue culminates in Sūn's rebellion against Heaven, during a time when he garnered a post in the celestial bureaucracy. Hubris proves his downfall when the Buddha manages to trap him under a mountain for five hundred years.

Only following this introductory story is the nominal main character, Xuánzàng, introduced. Chapters 8–12 provide his early biography and the background to his great journey. Dismayed that "the land of the South knows only greed, hedonism, promiscuity, and sins", the Buddha instructs the Bodhisattva Guānyīn to search Táng China for someone to take the Buddhist sutras of "transcendence and persuasion for good will" back to the East. Part of the story here also relates to how Xuánzàng becomes a monk (as well as revealing his past life as the "Golden Cicada" and comes about being sent on this pilgrimage by the Emperor Táng Tàizōng, who previously escaped death with the help of an underworld official).

The third and longest section of the work is Chapter 13–99, an episodic adventure story which combines elements of the quest as well as the picaresque. The skeleton of the story is Xuánzàng's quest to bring back Buddhist scriptures from Vulture Peak in India, but the flesh is provided by the conflict between Xuánzàng's disciples and the various evils that beset him on the way.

The scenery of this section is, nominally, the sparsely populated lands along the Silk Road between China and India, including Xinjiang, Turkestan, and Afghanistan. The geography described in the book is, however, almost entirely fantastic; once Xuánzàng departs Cháng'ān, the Táng capital and crosses the frontier (somewhere in Gansu province), he finds himself in a wilderness of deep gorges and tall mountains, all inhabited by flesh-eating demons who regard him as a potential meal (since his flesh was believed to give Immortality to whoever eats it), with here and there a hidden monastery or royal city-state amid the wilds.

The episodic structure of this section is to some extent formulaic. Episodes consist of 1–4 chapters, and usually involve Xuánzàng being captured and his life threatened, while his disciples try to find an ingenious (and often violent) way of liberating him. Although some of Xuánzàng's predicaments are political and involve ordinary human beings, they more frequently consist of run-ins with various goblins and ogres, many of whom turn out to be the earthly manifestations of heavenly beings (whose sins will be negated by eating the flesh of Xuanzang) or animal-spirits with enough Taoist spiritual merit to assume semi-human forms.

Chapter 13–22 do not follow this structure precisely, as they introduce Xuánzàng's disciples, who, inspired or goaded by Guānyīn, meet and agree to serve him along the way, in order to atone for their sins in their past lives.

- The first is Sun Wukong, or Monkey, previously "Great Sage Equal to Heaven", trapped by Buddha for rebelling against Heaven. He appears right away in Chapter 13. The most intelligent and violent of the disciples, he is constantly reproved for his violence by Xuánzàng. Ultimately, he can only be controlled by a magic gold band that the Bodhisattva has placed around his head, which causes him excruciating pain when Xuánzàng says certain magic words.

- The second, appearing in 19, is Zhu Bajie, literally Eight-precepts Pig, sometimes translated as Pigsy or just Pig. He was previously Marshal Tīan Péng, commander of the Heavenly Naval forces, banished to the mortal realm for flirting with the Princess of the Moon Chang'e. He is characterized by his insatiable appetites for food and sex, and is constantly looking for a way out of his duties, but is always kept in line by Sūn Wùkōng.

- The third, appearing in Chapter 22, is the river-ogre Sha Wujing, also translated as Friar Sand or Sandy. He was previously Great General who Folds the Curtain, banished to the mortal realm for dropping (and shattering) a crystal goblet of the Heavenly Queen Mother. He is a quiet but generally dependable character, who serves as the straight foil to the comic relief of Sūn and Zhū.

- Possibly to be counted as a fourth disciple is the third prince of the Dragon-King, Yùlóng Sāntàizǐ, who was sentenced to death for setting fire to his father's great pearl. He was saved by Guānyīn from execution to stay and wait for his call of duty. He appears first in Chapter 15, but has almost no speaking role, as throughout most of the story he appears in the transformed shape of a horse that Xuánzàng rides on.

Chapter 22, where Shā is introduced, also provides a geographical boundary, as the river of quicksand that the travelers cross brings them into a new "continent". Chapter 23–86 take place in the wilderness, and consist of 24 episodes of varying length, each characterized by a different magical monster or evil magician. There are impassably wide rivers, flaming mountains, a kingdom ruled by women, a lair of seductive spider-spirits, and many other fantastic scenarios. Throughout the journey, the four brave disciples have to fend off attacks on their master and teacher Xuánzàng from various monsters and calamities.

It is strongly suggested that most of these calamities are engineered by fate and/or the Buddha, as, while the monsters who attack are vast in power and many in number, no real harm ever comes to the four travelers. Some of the monsters turn out to be escaped heavenly animals belonging to bodisattvas or Taoist sages and spirits. Towards the end of the book there is a scene where the Buddha literally commands the fulfillment of the last disaster, because Xuánzàng is one short of the eighty-one disasters he needs to attain Buddhahood.

In Chapter 87, Xuánzàng finally reaches the borderlands of India, and Chapter 87–99 present magical adventures in a somewhat more mundane (though still exotic) setting. At length, after a pilgrimage said to have taken fourteen years (the text actually only provides evidence for nine of those years, but presumably there was room to add additional episodes) they arrive at the half-real, half-legendary destination of Vulture Peak, where, in a scene simultaneously mystical and comic, Xuánzàng receives the scriptures from the living Buddha.

Chapter 100, the last of all, quickly describes the return journey to the Táng Empire, and the aftermath in which each traveler receives a reward in the form of posts in the bureaucracy of the heavens. Sūn Wùkōng and Xuánzàng achieve Buddhahood, Wùjìng becomes the Golden Arhat, the dragon is made a Naga, and Bājiè, whose good deeds have always been tempered by his greed, is promoted to an altar cleanser, i.e. eater of excess offerings at altars.

Historical context

The classic story of the Journey to the West was based on real events. In real life, Xuanzang (born c. 602-664) was a monk at Jingtu Temple in late-Sui Dynasty and early-Tang Dynasty Chang'an. Motivated by the poor quality of Chinese translations of Buddhist scripture at the time, Xuanzang left Chang'an in 629, despite the border being closed at the time due to war with the Gokturks. Helped by sympathetic Buddhists, he travelled via Gansu and Qinghai to Kumul (Hami), thence following the Tian Shan mountains to Turfan. He then crossed what are today Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Afghanistan, into Gandhara, reaching India in 630. Xuanzang travelled throughout the Indian subcontinent for the next thirteen years, visiting important Buddhist pilgrimage sites and studying at the ancient university at Nalanda.

Xuanzang left India in 643 and arrived back in Chang'an in 646 to a warm reception by Emperor Taizong of Tang. He joined Da Ci'en Monastery (Monastery of Great Maternal Grace), where he led the building of the Big Wild Goose Pagoda in order to store the scriptures and icons he had brought back from India. He recorded his journey in the book Journey to the West in the Great Tang Dynasty . With the support of the Emperor, he established an institute at Yuhua Gong (Palace of the Lustre of Jade) monastery dedicated to translating into Chinese the scriptures he had brought back. His translation and commentary work established him as the founder of the Dharma character school of Buddhism. Xuanzang died on March 7, 664. The Xingjiao Monastery was established in 669 to house his ashes.

Popular stories of Xuánzàng's journey were in existence long before Journey to the West was written. In these versions, dating as far back as Southern Song, a monkey character was already a primary protagonist. Before the Yuan Dynasty and early Ming, elements of the Monkey story were already seen.

Main characters

Tripitaka or xuánzàng.

Xuánzàng (玄奘), or Táng-Sānzàng (唐三藏) (Táng-Sānzàng, meaning "dynasty monk–three baskets", referring to the Tripitaka, was a traditional honorific for a Buddhist monk), is the Buddhist monk who set out to India to retrieve the Buddhist scriptures for China. He is called Tripitaka in many English versions of the story. Although he is helpless when it comes to defending himself, the bodhisattva Guānyīn helps by finding him powerful disciples (Sūn Wùkōng, Zhū Bājiè, and Shā Wùjìng) who aid and protect him on his journey. In return, the disciples will receive enlightenment and forgiveness for their sins once the journey is done. Along the way, they help the giancarlo by defeating various monsters. The fact that most of the monsters and demons are trying to obtain immortality by eating Xuánzàng's flesh, and are even attracted to him as he is depicted as quite handsome, provides much of the plot in the story.

Monkey King (Emperor of Monkeys) or Sūn Wùkōng

Sūn Wùkōng is the name given to this character by his teacher, Patriarch Subhuti, and means "the one who has Achieved the Perfect Comprehension of the Extinction of both Emptiness and non-Emptiness"; he is called Monkey King or simply Monkey Emperor in English.

He was born out of a rock that had been dormant for ages in Flower Fruit Mountain that was inhabited/weathered by the sun and moon until a monkey sprang forth. He first distinguished himself by bravely entering the Cave of Water Curtains (pinyin: Shuǐlián-dòng ) at the Mountains of Flowers and Fruits ( Huāguǒ-shān ); for this feat, his monkey tribe gave him the title of Měi-hóuwáng ("handsome monkey-king"). Later, he started making trouble in Heaven and defeated an army of 100,000 celestial soldiers, led by the Four Heavenly Kings, Erlang Shen, and Nezha. Eventually, the Jade Emperor appealed to Buddha, who subdued and trapped Wukong under a mountain. He was only saved when Xuanzang came by him on his pilgrimage and accepted him as a disciple.

His primary weapon is the rúyì-jīngū-bàng ("will-following golden-banded staff"), which he can shrink down to the size of a needle and keep behind his ear, as well as expand it to gigantic proportions (hence the "will-following" part of the name). The staff, originally a pillar supporting the undersea palace of the East Sea Dragon King, weighs 13,500 pounds, which he pulled out of its support and swung with ease. The Dragon King, not wanting him to cause any trouble, also gave him a suit of golden armor. These gifts, combined with his devouring of the peaches of immortality and three jars of immortality pills while in Heaven, plus his ordeal in an eight-trigram furnace (which gave him a steel-hard body and fiery golden eyes), makes Wukong the strongest member by far of the pilgrimage. Besides these abilities, he can also pull hairs from his body and blow on them to transform them into whatever he wishes (usually clones of himself to gain a numerical advantage in battle). Although he has mastered seventy-two methods of transformations, it does not mean that he is restricted to seventy-two different forms. He can also do a jīndǒuyún ("cloud somersault"), enabling him to travel vast distances in a single leap. Wukong uses his talents to fight demons and play pranks. However, his behavior is checked by a band placed around his head by Guanyin, which cannot be removed by Wukong himself until the journey's end. Xuanzang can tighten this band by chanting the Tightening-Crown spell (taught to him by Guanyin) whenever he needs to chastise him.

Wukong's child-like playfulness is a huge contrast to his cunning mind. This, coupled with his acrobatic skills, makes him a likeable hero, though not necessarily a good role model. His antics present a lighter side in what proposes to be a long and dangerous trip into the unknown.

Zhū Bājiè ("Pig of the Eight Prohibitions") is also known as Zhū Wùnéng ("Pig Awakened to Power"), and given the name Pigsy or Pig in English.

Once an immortal who was the Tiānpéng-yuánshuǎi ("Field Marshal Tianpeng") of 100,000 soldiers of the Milky Way, during a celebration of gods, he drank too much and attempted to flirt with Cháng'é, the beautiful moon goddess, resulting in his banishment into the mortal world. He was supposed to be reborn as a human, but ended up in the womb of a sow due to an error at the Reincarnation Wheel, which turned him into a half-man half-pig monster. Staying within Yúnzhan-dòng ("cloud-pathway cave"), he was commissioned by Guanyin to accompany Xuanzang to India and given the new name Zhu Wuneng.

However, Wuneng's desire for women led him to Gao Village, where he posed as a normal being and took a wife. Later, when the villagers discovered that he was a monster, Wuneng hid the girl away. At this point, Xuanzang and Wukong arrived at Gao Village and helped subdue him. Renamed Zhu Bajie by Xuanzang, he consequently joined the pilgrimage to the West.

His weapon of choice is the jiǔchǐdīngpá ("Nine-toothed Rake|nine-tooth iron rake"). He is also capable of thirty-six transformations (as compared to Wukong's seventy-two), and can travel on clouds, but not as fast as Wukong. However, Bajie is noted for his fighting skills in the water, which he used to combat Sha Wujing, who later joined them on the journey. He is the second strongest member of the team.

Shā Wùjìng (literally meaninh "Sand Awakened to Purity"), given the name Friar Sand or Sandy in English, was once the Curtain Raising General, who stood in attendance by the imperial chariot in the Hall of Miraculous Mist. He was exiled to the mortal world and made to look like a monster because he accidentally smashed a crystal goblet belonging to the Heavenly Queen Mother during the Peach Banquet. The now-hideous immortal took up residence in the Flowing Sands River, terrorizing the surrounding villages and travelers trying to cross the river. However, he was subdued by Sūn Wùkōng and Zhū Bājiè when the Xuānzàng party came across him. They consequently took him in to be a part of the pilgrimage to the West.

Shā Wùjìng's weapon is the yuèyáchǎn ("Crescent-Moon-Shovel" or "Monk's Spade"). Aside from that, he knows eighteen transformations and is highly effective in water combat. He is about as strong as Bājiè, and is much stronger than Wùkōng in water. However, Bājiè can beat Wujing in a test of endurance, and Wùkōng can beat him out of water.

Shā Wùjìng is known to be the most obedient, logical, and polite of the three disciples, and always takes care of his master, seldom engaging in the bickeries of his fellow-disciples. Ever reliable, he carries the luggage for the travellers. Perhaps this is why he is sometimes seen as a minor character; the lack of any particular perks confers the lack of distinguishing and/or redeeming characteristics.

Wùjìng eventually becomes an Arhat at the end of the journey, giving him a higher level of exaltation than Bājiè, who is relegated to cleaning every altar at every Buddhist temple for eternity, but is still lower spiritually than Wùkōng or Xuānzàng who are granted Buddhahood.

List of Demons

There are many demons in the story. Examples are listed below:

- Black-Bear-Demon (pinyin: Hēixióngguài )

- Yellow Wind Demon (Huángfēngguài)

- Zhen Yuan Holy Man (He is not a demon, but an immortal, who got annoyed by those disciples who stole his precious immortal-fruits (Ginseng Fruits, 人参果).)

- White-Bone-Demon (pinyin: Báigǔjīng )

- Yellow Robe Demon (pinyin: Huángpáoguài )

- Gold-Horn and Silver-Horn (pinyin: Jīnjiǎo and Yínjiǎo )

- Red-Boy a.k.a. Holy Baby King (pinyin: Hóng-hái'ér ; Japanese: Kōgaiji )

- Tiger Power, Deer Power and Goat (or Antelope) Power

- Black River Dragon Demon (Hēi Shǔi Hé Yuan Lóng Gài)

- Carp Demon (Li Yu Jīng)

- Green-Ox-Demon (pinyin: Qīngniújīng )

- Scorpion-Demon (pinyin: Xiēzijīng )

- Six Ear Monkey Demon (a.k.a Fake Sun Wukong, Lìuěrmíhóu )

- Ox-Demon-King (pinyin: Niúmówáng ; Japanese: Gyūmaō )

- Demon Woman (Luo Cha Nǚ)

- Jade-Faced Princess (pinyin: Yùmiàn-gōngzhǔ ; Japanese: Gyokumen-kōshū )

- Boa Demon ( Hóng Shé Jīng )

- Nine-Headed Bird Demon (Jiǔ Tou Fu Ma)

- Seven-Spider-Demons (pinyin: Zhīzhū-jīng )

- Hundred-Eyed Taoist (Bǎi Yan Mo Jun)

- Green Lion Demon (pinyin: Qīngshījīng )

- White-Elephant-Demon (pinyin: Báixiàngjīng )

- Falcon Demon (Sun Jīng)

- Biqiu Country Minister a.k.a Deer Demon

- Gold-Nosed, White Mouse Demon (Lao Shu Jīng)

- Dream-Demon

Notable English-language translations

- Monkey: A Folk-Tale of China (1942), an abridged translation by Arthur Waley. For many years, the best translation available in English; it only translates thirty out of the hundred chapters. (Penguin reprint ISBN 0-14-044111-5 )

- Journey to the West , a complete translation by W.J.F. Jenner published by the Foreign Languages Press in Beijing 1955 (three volumes; 1982/1984 edition: ISBN 0-8351-1003-6 , ISBN 0-8351-1193-8 , ISBN 0-8351-1364-7 )

- The Journey to the West (1977–1983), a complete translation in four volumes by Anthony C. Yu. University of Chicago Press: HC ISBN 0-226-97145-7 , ISBN 0-226-97146-5 , ISBN 0-226-97147-3 , ISBN 0-226-97148-1 ; PB ISBN 0-226-97150-3 , ISBN 0-226-97151-1 ; ISBN 0-226-97153-8 ; ISBN 0-226-97154-6 .

Media adaptations

- Journey to the West: The Musical : A stage musical which received its world premiere at the New York Musical Theatre Festival on September 25, 2006.

- Monkey: Journey to the West : A stage musical version created by Chen Shi-zheng, Damon Albarn and Jamie Hewlett. It premiered as part of the 2007 Manchester International Festival at the Palace Theatre on June 28.

- The Monkey King : A production by the Children's Theater Company in Minneapolis, MN in 2005.

- A Chinese Odyssey by Stephen Chow.

- A Chinese Tall Story : 2005 live action movie starring Nicholas Tse as Xuánzàng.

- Heavenly Legend : A 1998 film by Tai Seng Entertainment starring Kung Fu kid Sik Siu Loong is partially based on this legend.

- Monkey Goes West : The Shaw Brothers's 1966 Hong Kong film (Cantonese: Sau yau gei. Also known as "Monkey with 72 Magic"

- The Forbidden Kingdom : 2008 live action movie starring Jackie Chan and Jet Li which is said to be based on the Legend of the Monkey King, the same legend as the TV show Monkey. [1]

Live action television

- Monkey (1978-1980): A well-known 1970s Japanese television series based on Journey to the West translated into English by the BBC.

- Journey to the West (1986): A TV series produced by CCTV.

- Journey to the West (1996): A popular series produced by Hong Kong studio TVB, starring Dicky Cheung.

- Journey to the West II (1998): The sequel to TVB's Journey to the West series, starring Benny Chan.

- The Monkey King (2001): Sci Fi Channel's TV adaptation of this legend, also called The Lost Empire .

- The Monkey King: Quest for the Sutra (2002): A loose adaptation starring Dicky Cheung, who also portrayed Sun Wukong in the 1996 TVB series.

- Saiyūki (2006): A Japanese television series starring the SMAP star Shingo Katori.

Comics, manga, and anime

- Alakazam the Great : One of the first anime films produced by Toei Animation , a retelling of first part of the story based on the characters designed by Osamu Tezuka.

- Gensōmaden Saiyūki : manga and anime series inspired by the legend. Follow-up series include Saiyūki Reload and Saiyūki Reload Gunlock .