- Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

- Biostatistics

- Environmental Health and Engineering

- Epidemiology

- Health Policy and Management

- Health, Behavior and Society

- International Health

- Mental Health

- Molecular Microbiology and Immunology

- Population, Family and Reproductive Health

- Program Finder

- Admissions Services

- Course Directory

- Academic Calendar

- Hybrid Campus

- Lecture Series

- Convocation

- Strategy and Development

- Implementation and Impact

- Integrity and Oversight

- In the School

- In the Field

- In Baltimore

- Resources for Practitioners

- Articles & News Releases

- In The News

- Statements & Announcements

- At a Glance

- Student Life

- Strategic Priorities

- Inclusion, Diversity, Anti-Racism, and Equity (IDARE)

- What is Public Health?

WTO TRIPS Waiver for COVID-19 Vaccines

Sharing the know-how behind making COVID-19 vaccines is key to scaling up production and addressing emerging variants.

A Q&A WITH ANTHONY D. SO, MD, MPA

The Biden administration announced it would seek a “TRIPS waiver” of intellectual property protections related to COVID vaccines.

In this Q&A, Anthony D. So, MD, MPA , a professor of the practice in International Health , explains the waiver and what it could mean for COVID-19 vaccines.

What’s the TRIPS waiver for COVID vaccines all about?

The TRIPS waiver refers to a proposal, advanced by the governments of South Africa and India, to the World Trade Organization to waive intellectual property rights protection for technologies needed to prevent, contain, or treat COVID-19 “until widespread vaccination is in place globally, and the majority of the world’s population has developed immunity.”

In 1995, when the World Trade Organization came into existence, those signing up as members agreed that in exchange for the lowering of barriers to trade, they would abide by the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, or TRIPS.

This Agreement, pushed by knowledge-based economies like the United States and the multinational, research-intensive pharmaceutical industry, imposed a base of protections for intellectual property rights, from patents to copyrights. Before this was negotiated, more than 50 countries did not recognize patent protection on pharmaceutical products. The TRIPS Agreement changed that, and after a transition period of 10 years, ratcheted up these requirements on all but the least developed countries.

Middle-income countries like India came into compliance by 2005. The TRIPS waiver just seeks to temporarily suspend these protections until the pandemic has ended, so the world can better access the knowledge needed to combat the worst pandemic in a century.

What’s the rationale behind waiving intellectual property protections for COVID vaccines?

Sharing the know-how behind making COVID-19 vaccines is key to not only scaling up production, but also bringing forward the second generation of vaccines we will need to address emerging variants.

No single vaccine manufacturer can produce enough vaccines to cover the globe, and demand has far outstripped supply, with high-income countries taking the lion’s share of reserved doses. Proponents of a TRIPS waiver wonder how it can be right for a multinational vaccine manufacturer to hold exclusive rights that can stop other firms from stepping up to meet the need for vaccines, particularly in markets not being served by current vaccine producers. They argue that the public already has paid once or twice for such innovation, either upfront in research and development (R&D) costs or through purchase guarantees of these products, or both.

Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine—one of two now in use based on an mRNA platform—was paid for largely by the U.S. government, and in fact, Moderna has pledged not to enforce its patents related to the COVID-19 vaccine during the pandemic. However, making the Moderna vaccine likely involves other companies’ patented equipment and processes as well, so waiving patent protections on one piece of the process may not help other companies make the entire “recipe.”

This is why a TRIPS waiver is considered important to ensure other vaccine manufacturers would have the freedom to operate. It should also be acknowledged that a TRIPS waiver may accelerate scaling up some COVID-19 vaccines where untapped capacity for vaccine production still exists, and it may also encourage existing vaccine producers to step up their technology transfer efforts.

By noting its willingness to move forward with text-based negotiations over a TRIPS waiver at the World Trade Organization, the United States signaled a seismic shift in policy. However, it is only the beginning of a process.

Who is opposing the TRIPS waiver and why?

Other high-income countries, from EU countries and the United Kingdom to Japan and Australia, have yet to join the United States in supporting negotiations for a TRIPS waiver. Multinational pharmaceutical companies have vocally opposed the waiver, and disclosure forms from the first quarter of 2021 reveal that over 100 lobbyists had been enlisted to oppose the TRIPS waiver.

The main arguments boil down to protecting the incentive for future pharmaceutical innovation. The idea is that companies will be reluctant to invest in new technology if they feel that they cannot reap full financial benefit from their successes.

Yet before COVID-19 hit, R&D for pandemic vaccines was largely neglected by the private sector, and public financing understandably had to support this work. Many of the first COVID-19 vaccines that came to market relied on tax dollars to enable their effective development.

One of the key aspects of producing successful COVID-19 vaccines has been the process of stabilizing the COVID-19 spike protein. This innovation relied largely on public funding, and all of the vaccines currently on the U.S. market rely on this technology. But although they all benefited from publicly funded intellectual property, no vaccine company has stepped forward to join a global effort to voluntarily share its know-how through the COVID-19 Technology Access Pool (C-TAP), launched by WHO with the support of Costa Rica and 40 member state cosponsors.

Another question raised by opponents of the waiver is: Have companies been able to make a strong return on their investment? The answer appears to be yes. In a market almost entirely created by public sector purchase of vaccines for a pandemic, Pfizer brought in $3.5 billion in COVID-19 vaccine revenues in the first quarter of this year, with estimated profit margins in the high 20% range, by far its greatest revenue generator. Pfizer’s partner, BioNTech, received upfront public financing, both from the German government and the European Investment Bank, while Pfizer itself has secured 6 billion dollars thus far from the U.S. government in guaranteed purchases of its COVID-19 vaccine. So even if the TRIPS waiver were to enable other vaccine producers to meet the huge unmet demand, it is hard to argue that the public sector has not already provided multibillion-dollar incentives to bring forward needed innovation.

The pharmaceutical industry has also argued that the TRIPS waiver will not speed the scale-up of COVID-19 vaccines. This argument reflects the fact that the production process is very complex and difficult to develop without extensive support from existing manufacturers.

This may be particularly true for mRNA technology. While mRNA vaccine candidates are emerging in India and China as well, the intellectual property landscape for mRNA vaccines is highly fragmented, with a handful of pharmaceutical companies holding half of these patent applications. The TRIPS waiver would clear the path for these firms to move forward, as they enter clinical testing, without concern over conflicting patent claims that may not be resolved at pandemic speed.

Unlike Pfizer and Moderna, which make mRNA vaccines, AstraZeneca/Oxford has struck many more technology transfer agreements with vaccine producers in low- and middle-income countries for its vaccine based on adenovirus vector technology, which is easier to produce and distribute. Its vaccine price of $3 per dose is also less than half that of Pfizer/BioNTech’s vaccine in the African Union.

With first-generation vaccine producers already focused on booster doses to take on variants affecting high-income countries, will they be as focused when a variant spreads through lower-income country markets that largely remain unvaccinated? Two-thirds of the WTO’s members support the TRIPS waiver because they are unsure that their COVID-19 public health needs will be met by upholding patent protections as usual. Perhaps this reflects the experience of these countries’ governments in securing access to Pfizer/BioNTech vaccines, let alone the building blocks of knowledge to develop second-generation vaccines. Pfizer has been asking governments to put sovereign assets—such as federal bank reserves, embassy buildings, or military bases—as a guarantee against indemnifying the cost of future legal cases.

What else, beyond resolving intellectual property issues, is necessary to scale up vaccine production?

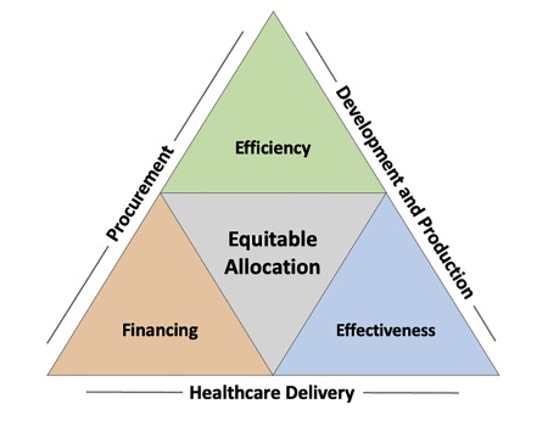

These negotiations over a TRIPS waiver will not take place overnight, nor will scaling up the technology transfer and ramping up the manufacture of COVID-19 vaccines. In a perspective piece for Cell’s new translational science journal, we recently discussed the complex issues involved in scaling up vaccine production and, importantly, ensuring that these vaccines make their way not only to high-income countries, but also more equitably to those in need across the globe. This will involve, among other things:

- Public investment in technology transfer

- Contracting of existing and new manufacturing facilities

- Sourcing other inputs like glass vials

- Pooled procurement facilities, from UNICEF to the Pan American Health Organization’s Revolving Fund for Vaccine Access, to buy and deliver the vaccines effectively.

We will also need to prioritize scaling up second-generation vaccines that have been adapted to address emerging variants or that are better suited for delivery where ultra-cold chains do not exist.

Source: So AD, Woo J. Achieving path-dependent equity for global COVID-19 vaccine allocation. Med 2021; 2(4): P373-377. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medj.2021.03.004

What are the next steps?

For years to come, we will need COVID-19 vaccines. A sustainable and affordable pipeline—one that will deliver in a timely way to all in need, not just to those in wealthy countries—must be put in place.

In the best-case scenario, a TRIPS waiver for sharing COVID-19-related knowledge and technology can lay an important foundation to an innovation ecosystem that ensures a fairer path out of the pandemic than we took going into the pandemic.

But no one doubts that there is a tough road ahead in negotiating the text to this waiver and in all the work that follows so that it might make an effective difference. Other questions will naturally arise, including the approach to intellectual property for tests and treatments for COVID-19, as well as the sharing of key research findings and data.

In the near term, the U.S. should also commit to sharing-and-exchange mechanisms for COVID-19 vaccines, especially as uptake of vaccines slows.

We had proposed a temporal trade, for example, on the U.S.-reserved doses of the not-yet-approved AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine with countries waiting and ready to use this vaccine now. By just swapping our line in the queue, vaccine doses may reach those in desperate need sooner. More such arrangements will be needed, particularly since AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine supplies globally have since been disrupted with the unfolding COVID-19 resurgence in India, from where much of its manufacture had been sourced.

In the meantime, the world must not lose any time in scaling up the public sector investment in the rest of the supply chain, from manufacturing to logistical delivery of these vaccines. The U.S. can lead a coalition of the willing to build upon and extend the use of such vaccine platforms through technology transfer. History will remember what is done to meet this moment.

Anthony So, MD, MPA , is a professor of the practice in International Health and the founding director of the Innovation+Design Enabling Access (IDEA) Initiative .

RELATED CONTENT

- The New Technology Behind COVID-19 RNA Vaccines and What This Means for Future Outbreaks

- Can COVID-19 Vaccines Be Mandatory in the U.S. and Who Decides?

- Enhancing Public Trust and Health with COVID-19 Vaccination

Related Content

What to Know About the Updated COVID Vaccine for Fall, Winter 2024–25

Why We’re Still Waiting for a Pandemic Treaty

Why COVID Surges in the Summer

As Global Health Programs Transition to Local Entities, Researchers Turn an Eye toward Sustainability

Public Health Prep for the 2024 Paris Olympics

Programs submenu

Regions submenu, topics submenu, weapons in space: a virtual book talk with dr. aaron bateman, u.s.-australia-japan trilateral cooperation on strategic stability in the taiwan strait report launch, dahlia scheindlin on israeli opinion—gaza: the human toll.

- Abshire-Inamori Leadership Academy

- Aerospace Security Project

- Africa Program

- Americas Program

- Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy

- Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative

- Asia Program

- Australia Chair

- Brzezinski Chair in Global Security and Geostrategy

- Brzezinski Institute on Geostrategy

- Chair in U.S.-India Policy Studies

- China Power Project

- Chinese Business and Economics

- Defending Democratic Institutions

- Defense-Industrial Initiatives Group

- Defense 360

- Defense Budget Analysis

- Diversity and Leadership in International Affairs Project

- Economics Program

- Emeritus Chair in Strategy

- Energy Security and Climate Change Program

- Europe, Russia, and Eurasia Program

- Freeman Chair in China Studies

- Futures Lab

- Geoeconomic Council of Advisers

- Global Food and Water Security Program

- Global Health Policy Center

- Hess Center for New Frontiers

- Human Rights Initiative

- Humanitarian Agenda

- Intelligence, National Security, and Technology Program

- International Security Program

- Japan Chair

- Kissinger Chair

- Korea Chair

- Langone Chair in American Leadership

- Middle East Program

- Missile Defense Project

- Project on Critical Minerals Security

- Project on Fragility and Mobility

- Project on Nuclear Issues

- Project on Prosperity and Development

- Project on Trade and Technology

- Renewing American Innovation

- Scholl Chair in International Business

- Smart Women, Smart Power

- Southeast Asia Program

- Stephenson Ocean Security Project

- Strategic Technologies Program

- Sustainable Development and Resilience Initiative

- Wadhwani Center for AI and Advanced Technologies

- Warfare, Irregular Threats, and Terrorism Program

- All Regions

- Australia, New Zealand & Pacific

- Middle East

- Russia and Eurasia

- American Innovation

- Civic Education

- Climate Change

- Cybersecurity

- Defense Budget and Acquisition

- Defense and Security

- Energy and Sustainability

- Food Security

- Gender and International Security

- Geopolitics

- Global Health

- Human Rights

- Humanitarian Assistance

- Intelligence

- International Development

- Maritime Issues and Oceans

- Missile Defense

- Nuclear Issues

- Transnational Threats

- Water Security

TRIPS Waivers and Pharmaceutical Innovation

Blog Post by Chris Borges

Published March 15, 2023

By Christopher Borges

On June 22, 2022, the World Trade Organization (WTO) approved a waiver of intellectual property (IP) protections for COVID-19 vaccine patents, previously secured under the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). The WTO is currently considering expanding this waiver to include COVID-19 diagnostics and therapeutics in addition to vaccines. As the U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC) investigates the implications of this expansion, it is important to understand what this waiver is intended to accomplish, explore whether it will be effective in the short term, and examine the long run impacts on the bio-pharmaceutical innovation system.

What Is the TRIPS Agreement?

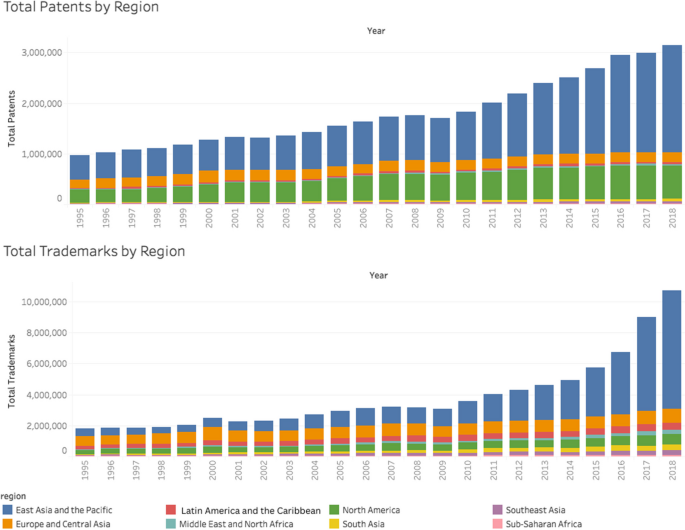

TRIPS refers to a WTO agreement incorporating obligations related to IP protection into the global rules-based trading system. Active since 1995, TRIPS requires most WTO members to adhere to minimum rules for the protection of IP — such as patents, copyrights, and trademarks — and enforce these commitments domestically. By agreeing to respect IP protections, member countries receive certain benefits in return. For example, TRIPS allows WTO members to make exceptions to patent rights so long as they are “limited” and do not violate the “normal” use of the patent. States often employ this provision to advance their science and technology base by allowing their researchers to use patented research tools and techniques.

Why Was There a Call to Waive TRIPS IP Protections for COVID-19 Vaccines?

Despite COVID-19 vaccines being the fastest developed vaccines in history, global access to these vaccines remains uneven. The United States first administered COVID-19 vaccines in December 2020, yet, per the University of Oxford, as of March 1st, 2023, only 28 percent of people in low-income countries have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine.

Most of the vaccines approved for use are developed by firms in the United States, Europe, China, and Russia, but the Western-made mRNA vaccines are the most effective and therefore the most in-demand vaccines on the market. The wealth of Western nations along with the geographic distribution of mRNA vaccine producers enabled them to reserve large vaccine supplies early in the pandemic, effectively shutting out lower-income countries. Low-income countries currently have a 28 percent vaccination rate, whereas the United States had vaccinated 28 percent of its population by March 23rd, 2021.

Citing this disparity, many developing nations called on the international community to waive TRIPS IP protections for COVID-19 vaccines, based on the notion that allowing any company to manufacture the vaccines will boost production and, ultimately, vaccinations. South Africa and India first proposed a TRIPS waiver for COVID-19 vaccines in October 2020, drawing considerable support from over 100 lower-income countries. High-income countries, however, were initially opposed to the waiver on the grounds that it would have an adverse effect on innovation, drug quality, and drug safety. Negotiations continued for nearly two-years until the waiver was ultimately agreed to, with high-income countries easing their objections once they were sufficiently supplied with vaccines.

What Does the COVID-19 Vaccine Waiver Do?

The COVID-19 vaccine waiver suspends certain requirements regarding the use of COVID-19 vaccine patents, such as ingredients and manufacturing processes. With this waiver, states can authorize domestic manufacturers to produce COVID-19 vaccines without the permission of the patent rights holder and, crucially, to export those vaccines to other countries.

The waiver was designed to be a short term action, taken as an emergency measure in the midst of a global pandemic. However, as implementing the waiver required all 164 WTO members to agree, it took nearly two years of deliberation to come to consensus. By the time WTO members agreed to the waiver in June 2022, the response to the pandemic had progressed considerably and over 12 billion vaccine doses had been administered.

Why Are There Calls to Expand the TRIPS Waiver?

The WTO is currently considering if the waiver should be expanded to include the production and supply of COVID-19 diagnostics and therapeutics. This would cover a broad category of products, including products utilized for diseases and conditions beyond COVID-19.

To date, the FDA has approved dozens of COVID-19 therapeutics. Oral antiviral treatments paxlovid and molnupiravir were quickly developed by Pfizer and Merck, respectively, and approved by the FDA in late 2021. Remsidivir, a therapeutic first developed in 2009 by Gilead Sciences, was repurposed to treat COVID-19 after studies concluded that it reduces the risk of hospitalization and death in high-risk patients by up to 87 percent.

The efficacy of these COVID-19 treatments prompted low-income countries and international organizations such as UNICEF to demand an expansion of the TRIPS waiver to include these drugs along with diagnostic tests. To continue combating COVID-19 — the World Health Organization (WHO) reported 70,000 new cases on March 1st — they assert that all medical tools must be made available to the fullest extent.

How Effective Is the TRIPS Waiver? How Effective Would the Expansion Be?

The COVID-19 TRIPS waiver has had minimal impact on overall vaccine access. As of the end of 2022, no country had declared intent to make use of the TRIPS waiver.

Global vaccine demand had plummeted by the time the TRIPS waiver was agreed to. In December 2022, the board of Gavi, a nonprofit that supplies vaccines to low- and middle-income countries voted to stop supplying COVID-19 vaccines to most nations due to lack of demand. This drop in demand indicates that the primary issue impeding vaccinations today is not lack of supply, but lack of distribution capacity. Administering COVID-19 vaccines across a population requires significant healthcare infrastructure which some developing countries lack , such as refrigeration to keep vaccines at low temperatures and a well-trained healthcare workforce. To increase global vaccination rates, efforts should focus on building healthcare infrastructure and distribution capacity, not facilitating additional vaccine production.

Currently, the supply of treatments to COVID-19 far outstrips demand as well. This is largely because secure IP rights have incentivized drug inventors to enter over 140 partnerships with manufacturers worldwide, boosting supply while transferring technology and tacit knowledge to these foreign firms. Secure IP rights assure companies that their inventions will not be stolen in the short-term, thereby allowing them to reveal their secrets and participate in these productive manufacturing partnerships. Expanding the TRIPS waiver to therapeutics would have little added benefit to access.

Further, expanding the TRIPS waiver to therapeutics will disincentivize the creation of new COVID-19 treatments. Biopharmaceutical research is expensive and risky — the R&D process for new drugs costs close to $1 billion on average, and only 12 percent of drugs which enter clinical trials are ultimately approved for use. Companies will simply not invest in creating new therapeutics if they will lose ownership of their IP should their huge and risky investment prove fruitful.

Can the COVID-19 TRIPS Waivers Damage the Biopharma Innovation Ecosystem?

IP rights advocates point out that undermining IP protections will weaken incentives for pharmaceutical companies to innovate. Bio-pharmaceutical research and development (R&D) costs are so high that private capital will not invest without the promise of exclusive rights on the output. While quick government action and spending in the early days of the pandemic accelerated the development of COVID-19 vaccines, the rapid response to COVID-19 was built on the long-term stability of IP protections.

For example, the science and technology behind mRNA vaccines, an essential tool in the fight against COVID-19, was supported over decades by both far-sighted government investment as well as through commercialization drawing on considerable private capital expecting a return. The success of mRNA vaccines was not a slam dunk, yet investors took the risk on the understanding that they would receive substantial returns should the technology prove effective. Throughout this long and risky R&D process, the secure and predictable assignment of property rights allowed universities, government labs, and large and small companies to cooperate effectively to develop mRNA vaccine technology, and, ultimately, deliver vaccines in record time.

By removing IP protections on COVID-19 vaccines and treatments, the WTO is weakening the incentives for companies to invest in financially risky technology in the future as, even if their venture is successful, they may lose IP protections which allow them to recoup their investment.

How Will the TRIPS Waivers Impact U.S. National Security?

Global trends such as climate change, urbanization, and rising meat consumption make future pandemics more likely. It is critical that the United States maintain a dynamic and innovative pharmaceutical industry to combat this threat.

Government action, in partnership with private industry, in the early days of the pandemic accelerated the rapid development and scale up of COVID-19 vaccines. Through a myriad of policies such as pre-ordering millions of vaccine doses, Operation Warp Speed expedited the development and roll-out of vaccines by months, saving thousands of lives.

While quick action played a key role in the overall response, however, a crucial lesson from COVID-19 is that waiting until a pandemic is declared to act will be too late. mRNA vaccine technology was developed over decades and sustained by a dynamic and innovative bio-pharmaceutical ecosystem that connects universities, government labs, and large and small firms in the industry. Because of this large body of pre-existing work, much of which was facilitated through the security and predictability afforded by IP protections, pharmaceutical companies were able to prototype COVID-19 vaccines within days of receiving the viral genome. Further, this ecosystem not only rapidly produced dozens of COVID-19 therapeutics, but also possessed an existing supply of drugs that proved effective in treating COVID-19. Without a long-standing healthy innovation ecosystem, this could not have happened.

TRIPS waivers undermine the U.S. pharmaceutical industry by degrading the IP protections which are essential to the pharmaceutical innovation ecosystem. Less innovation in the pharmaceutical industry means fewer vaccines and drugs in the future, leaving the United States and other nations less prepared for future pandemics and other health emergencies.

Christopher Borges is a research intern with the Renewing American Innovation project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C.

The Perspectives on Innovation Blog is produced by the Renewing American Innovation Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a private, tax-exempt institution focusing on international public policy issues. Its research is nonpartisan and nonproprietary. CSIS does not take specific policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this publication should be understood to be solely those of the author(s).

© 2024 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. All rights reserved.

Chris Borges

Programs & projects.

- Standards and Intellectual Property Rights for Innovation

- Strengthening the U.S. Innovation Ecosystem

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Health Hum Rights

- v.24(2); 2022 Dec

Improving Access to COVID-19 Vaccines: An Analysis of TRIPS Waiver Discourse among WTO Members, Civil Society Organizations, and Pharmaceutical Industry Stakeholders

Jillian kohler.

A professor at the University of Toronto Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, and Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy, Toronto, Canada, and founding director of the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Governance, Accountability and Transparency in the Pharmaceutical Sector.

A JD candidate at the University of Toronto Faculty of Law, Toronto, Canada, and research associate at the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Governance, Accountability and Transparency in the Pharmaceutical Sector.

Lauren Tailor

A PhD student at the University of Toronto Dalla Lana School of Public Health, Toronto, Canada, and a research assistant at the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Governance, Accountability and Transparency in the Pharmaceutical Sector.

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, international access to COVID-19 vaccines and other health technologies has remained highly asymmetric. This inequity has had a particularly deleterious impact on low- and middle-income countries, engaging concerns about the human rights to health and to the equal enjoyment of the benefits of scientific progress enshrined under articles 12 and 15 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. In response, the relationship between intellectual property rights and public health has reemerged as a subject of global interest. In October 2020, a wholesale waiver of the copyright, patent, industrial design, and undisclosed information sections of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property (TRIPS Agreement) was proposed by India and South Africa as a legal mechanism to increase access to affordable COVID-19 medical products. Here, we identify and evaluate the TRIPS waiver positions of World Trade Organization (WTO) members and other key stakeholders throughout the waiver’s 20-month period of negotiation at the WTO. In doing so, we find that most stakeholders declined to explicitly contextualize the TRIPS waiver within the human right to health and that historical stakeholder divisions on the relationship between intellectual property and access to medicines appear largely unchanged since the early 2000s HIV/AIDS crisis. Given the WTO’s consensus-based decision-making process, this illuminates key challenges faced by policy makers seeking to leverage the international trading system to improve equitable access to health technologies.

Introduction

Article 12 of the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) recognizes every person’s human right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, while article 15 recognizes every person’s human right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress. 1 Taken together, this necessarily includes every person’s right to access lifesaving health technologies, such as vaccines, pharmaceuticals, personal protective equipment, and diagnostics. Yet inequities persist, with as many as two billion people in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) lacking regular access to essential medicines. 2

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, global access to COVID-19 vaccines has remained highly asymmetric despite efforts by global institutions, such as COVAX, to advance such access. 3 When combined with general product shortages, price gouging, export restrictions on health supplies, vaccine manufacturing know-how constraints, and “my nation first” procurement approaches by high-income countries, equitable access to COVID-19 diagnostics and health technologies has been severely undermined. 4 This inequity in access to medicines and health technologies has had a particularly deleterious impact on vulnerable groups throughout the pandemic, notably in LMICs. 5 Two years since the start of the pandemic, several high-income countries have achieved full vaccination coverage in 70%–99% of their populations, while only 15.8% of people in low-income countries have received at least a single dose. 6

Amid this unequal access to essential medicines and health technologies, the relationship between intellectual property rights and public health has reemerged as a subject of global concern. Pursuant to the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement), all World Trade Organization (WTO) members have an obligation to respect patents issued within their domestic intellectual property (IP) systems irrespective of a patented invention’s initial country of origin. 7 This includes all patents that protect technology essential to the manufacture of COVID-19 vaccines.

Patents are a type of intellectual property right that provides inventors with the temporary right to exclude others from making, selling, or importing their patented technology. 8 As such, patents serve to limit supply and raise prices when manufacturers exercise their monopoly power to under-produce needed pharmaceuticals or charge prices that are out of reach for the majority of populations. 9 These issues are not new and have been raised in discussions surrounding the supply of pharmaceuticals for major diseases, including HIV/AIDS and hepatitis C. 10 Given that nearly all COVID-19 vaccines approved for use are protected by at least one active or pending patent, similar concerns have been raised in the production of COVID-19 vaccines and the associated consequences that this has on health equity. 11

In October 2020, a wholesale waiver of the copyright, patent, industrial design, and undisclosed information sections of the TRIPS Agreement was proposed by India and South Africa at the WTO on the basis that such a measure would be necessary to ensure that intellectual property rights would not interfere with “timely access to affordable medical products ... or to [the] scaling-up of research, development, manufacturing and supply of medical products essential to combat[ing] COVID-19.” 12 In May 2021, the waiver was clarified as intended to apply to all COVID-19-related health products and technologies, including vaccines, therapeutics, medical devices, and personal protective equipment. 13 In March 2022, a compromise between the European Union, India, South Africa, and the United States was proposed to narrow the applicability of the waiver to just COVID-19 vaccines. 14 The compromise also sought to limit the availability of the waiver to only those countries that exported less than 10% of the world’s vaccines in 2021. 15 Government responses to the waiver and its proposed alternatives have been divided, but as of June 2022, WTO members agreed to a modified version of the limited March 2022 waiver applicable for five years to COVID-19 vaccines. 16 Further conditions notably include a restriction on the waiver’s availability to only developing country WTO members, country obligations to prevent the re-exportation of products made under the waiver, and a six-month extension of discussions on expanding the waiver’s scope to COVID-19 therapeutics and diagnostics. 17

To better understand the justifications and implications of the TRIPS waiver negotiations and June 2022 compromise, we identify and evaluate the positions of WTO members and other key stakeholders with respect to the waiver and its relationship to health as a human right. In doing so, we find that historical stakeholder identities and positions with respect to IP and access to medicines have remained largely unchanged. Given the consensus-based decision-making at the WTO, this suggests that political and structural barriers continue to play a large role in limiting policy makers’ ability to leverage the international trading system to improve equitable access to health technologies.

Methodology

A descriptive, qualitative study drawing on critical policy studies methodologies, focusing on how interests, values, and normative assumptions shape and inform policy formation and implementation, was conducted to analyze the public statements of WTO members, pharmaceutical stakeholders, and civil society organizations with respect to the TRIPS waiver. 18 In particular, a combined inductive and deductive thematic analysis was employed to identify reoccurring TRIPS waiver position rationales expressed across each stakeholder and position class and to specifically search for rationales grounded in human rights-related appeals. 19 Data were independently abstracted by AW and LT, with JK resolving any discrepancies through an additional round of review.

Document identification

Official WTO member positions on the TRIPS waiver were sourced from WTO General Council and TRIPS Council meeting minutes from October 2020 to June 2022, as well as all official WTO member submissions related to the COVID-19 TRIPS waiver. 20 Based on these documents, a final list of all WTO members and their positions with respect to the TRIPS waiver was compiled. This list was then verified for consistency with an internal Médecins Sans Frontières policy tracker, which the organization used to construct its public infographic on TRIPS waiver country positions and shared with the authors upon request. 21

Thirty statements from over 350 civil society organizations included for analysis were extracted from submissions to the WTO’s official COVID-19 public consultation docket and the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives TRIPS COVID-19 waiver civil society letter repository (see Appendix 1, available upon request). 22 Sixty-six pharmaceutical companies were included for analysis and were selected based on size (top 20 multinational companies by 2020 revenue) and involvement in COVID-19 product development (COVAX suppliers), with all TRIPS waiver-related press releases recorded. 23 Official statements made by pharmaceutical trade organizations Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, Biotechnology Innovation Organization, International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations, and European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations were also queried (see Appendix 2, available upon request).

Document analysis

Documents were analyzed to identify the following elements: (1) country/organization identity, (2) country/organization position with respect to the TRIPS waiver (support, neutral or undetermined, opposed), and (3) country/organization rationale for their TRIPS waiver position. Stakeholder positions with respect to the TRIPS waiver were determined based on their explicit endorsement or rejection of any iteration of the waiver before the March 2022 compromise, or their qualitative expressions of support for or objection to any iteration of the waiver before the March 2022 compromise. Stakeholders whose positions were expressed in multiple documents were deemed to have adopted the position expressed in the document reporting their most recent public statement. Stakeholders who released statements that did not clearly express support or objection to the TRIPS waiver were classified as neutral or undetermined and, due to the limited public statements available in this category, were not analyzed further for their position rationales. Explicit references to “human rights” or rights-based assertions to health found in these documents were separately extracted for analysis.

Overall, the majority of WTO members and surveyed civil society organizations expressed support for a COVID-19 TRIPS waiver—either in its original October 2020 form or limited March 2022 form. By contrast, nearly all pharmaceutical industry stakeholders who issued public statements voiced opposition to all iterations of the TRIPS waiver. While these positions align strongly with the historical approaches of these stakeholders, a survey of the specific rationales presented by each provides greater insight into the primary sources of axiomatic contention during the COVID-19 TRIPS waiver discussions. The following section provides a breakdown of each of these stakeholder groups’ positions with respect to the waiver, as well as the dominant rationales offered for these positions.

WTO members

Until June 2022, approximately 59% of WTO members expressed support for a TRIPS waiver, either as outright sponsors or through favorable endorsement of the waiver. Approximately 21% of members expressed opposition to the TRIPS waiver (with 28 of the 35 opposing members belonging to the European Union or the European Union delegation itself). The remaining 20% of member positions were undetermined, either because they did not publicly comment on the TRIPS waiver or because their comments refrained from expressing a definitive position with respect to the waiver. The breakdown of WTO member positions and their position rationales is outlined in Table 1 .

WTO member positions regarding the proposed TRIPS waiver

WTO member rationales for supporting a TRIPS waiver

WTO members in support of the TRIPS waiver advanced four main arguments: (1) the TRIPS waiver is required to address IP-based barriers to access that the existing voluntary and compulsory licensing system is ill-equipped to manage; (2) the TRIPS waiver is important as a tool for promoting further COVID-19 solutions that are consistent with the human right to health; (3) the TRIPS waiver should include vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics, since a waiver just for vaccines would be insufficient to adequately address COVID-19; and (4) the TRIPS waiver is a legitimate trade policy tool under the existing WTO rules. Below, each rationale is discussed in further detail.

- IP is a barrier to access that cannot be addressed by voluntary or compulsory licensing . Members in support of the TRIPS waiver all adopted the position that IP is actively serving as a supply barrier by preventing the mass manufacture of needed COVID-19 vaccines, therapeutics, and medical devices. Many further argued that this barrier cannot be adequately addressed through voluntary licensing agreements with manufacturers or by issuing compulsory licenses to expand supply. South Africa emphasized that voluntary licensing agreements suffer from a lack of transparency, impose geographic restrictions that often prohibit export even to developing countries, and typically have only a nominal effect on increasing overall market supply. 24 Many countries also argued that the country-by-country and product-by-product approach to compulsory licensing prescribed under articles 31 and 31 bis of the TRIPS Agreement, which enable countries to manufacture and import generic versions of patented products without a patent owner’s consent, undermined the cross-border and widespread use of compulsory licenses required to respond to an international pandemic. India emphasized that ownership disputes among COVID-19 vaccine patent holders would likely compound delays in the articles 31 and 31 bis processes, since countries would potentially need to identify and send notice to multiple litigating owners to ensure compliance with TRIPS compulsory licensing procedures. 25 A lack of domestic legal capacity to engage in compulsory licensing was also highlighted by some states as further support that compulsory licensing is inadequate for supplying COVID-19 vaccines, therapeutics, and medical devices at an international scale. 26

- A TRIPS waiver is a tool consistent with promoting the human right to health . Several WTO members highlighted the sharp inequities among high-income and low-income countries regarding access to COVID-19 vaccines. For example, Bangladesh underscored the effects of vaccine nationalism and the lack of access faced by least developed countries, highlighting that the richest 16% of the world had “pre-booked” the majority of vaccines until 2025. 27 In response to claims by opposing members that COVAX, rather than a TRIPS waiver, was the solution to ensuring equity, supporting members emphasized that “the problem with philanthropy [COVAX] is that it cannot buy equality.” 28 In a position summary document submitted by TRIPS waiver sponsors in September 2021, they underscored that the adoption of the TRIPS waiver would act “as an important political, moral, and economic lever towards encouraging solutions aimed at global equitable access to COVID-19 health products and technologies.” 29 The preambular text of the document emphasized that in seeking equitable health outcomes, the TRIPS waiver was consistent with “the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health” protected under article 12 of the ICESCR, as well as the “bold commitment” under United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 3 to ending communicable diseases, achieving universal health coverage, and providing access to safe and effective medicines and vaccines for all. 30

- A TRIPS waiver for just vaccines is insufficient . Several supporting members emphasized the importance of including all relevant health technologies—rather than just vaccines—within the scope of the waiver. In particular, sponsors urged WTO members to recall that “vaccines are necessary but not sufficient” and that personal protective equipment, diagnostics, ventilators, and therapeutics are all essential to preventing the spread and ensuring the treatment of COVID-19. 31

- A TRIPS waiver is an established and accepted option under existing WTO rules . Many supporting members highlighted that under article IX.3 of the WTO Marrakesh Agreement, waivers of obligations imposed under WTO trade agreements can be legitimately employed in exceptional circumstances. 32 In the October 2020 TRIPS Council meeting, this was affirmed by the WTO Secretariat, which stated that the Ministerial Conference “may decide to waive an obligation imposed on a Member by the Marrakesh Agreement or any of the [WTO’s] multilateral trade agreements.” 33 Supporting members have argued that approving a temporary TRIPS waiver to address urgent public health needs during the COVID-19 pandemic should thus be seen as consistent with, rather than an exception to, the rules-based multilateral trading system. 34

WTO member rationales for opposing a TRIPS waiver

Four primary rationales were advanced by WTO members opposed to the TRIPS waiver: (1) a TRIPS waiver would not be effective in increasing global supplies since patents and the TRIPS Agreement are not a barrier to access; (2) access to needed COVID-19 health technologies can be addressed through nominal modifications to the TRIPS compulsory licensing system; (3) a TRIPS waiver would introduce legal uncertainty to the international system, thus undermining existing licensing partnerships that are essential to expanding access; and, (4) a TRIPS waiver would undermine the growth of the IP-dependent health technology sector, contrary to domestic development interests. Below, each rationale is discussed in further detail.

- Patents and existing TRIPS obligations are not a barrier to access . Nearly all opposing members endorsed a view that the patent and other IP protection obligations mandated under the TRIPS Agreement are not a primary factor responsible for limiting access to needed COVID-19 vaccines, therapeutics, or medical devices. Instead, members urged that temporary demand shocks, manufacturing capacity constraints, and supply chain delays were “much more likely to have an impact on access than [intellectual property rights].” 35 Several members cited a 2021 interview with the Serum Institute of India’s CEO Adar Poonawalla, who stated that he believed global supply shortages were due to short-term scale-up delays rather than insufficient licensing to generic manufacturers by patent owners. 36

- Access to needed COVID-19 vaccines, therapeutics, and medical devices can be addressed through minor modifications to existing compulsory licensing rules. The European Union suggested that any IP-related access challenges arising during COVID-19 could instead be addressed through nominal changes to the TRIPS articles 31 and 31 bis compulsory licensing framework. In particular, the European Union argued that delays arising from the system’s existing country-by-country and product-by-product notification requirements could be overcome by implementing an emergency uniform notification requirement. 37 Under this alternate proposal, members would provide the WTO Secretariat with a single compulsory licensing notice outlining all vaccines and recipient countries that they planned on supplying under compulsory license, thus reducing alleged administrative burdens to compulsory licensing faced by members in support of the waiver.

- A TRIPS waiver would undermine existing voluntary licensing partnerships . Several members emphasized that a TRIPS waiver would do more harm than good by destabilizing the international IP framework, and in doing so, jeopardize existing voluntary licensing partnerships between patent holders and third-party manufacturers. In particular, Switzerland highlighted the importance of a “safe regulatory framework” that is “predictable and accountable,” and argued that the TRIPS waiver risked undermining the efforts of the 300+ international partnerships currently working to build production capacity. 38 The need for legal stability to ensure productive and effective technology transfer between originator and generic manufacturers was also underscored.

- A TRIPS waiver would undermine the development of domestic health technology industries . Several WTO members cited concerns that a TRIPS waiver would undermine innovation in the pharmaceutical sector, thus harming the development of their local industries. For example, while Chile acknowledged that “[the protection of] IP is not an end in itself,” it nonetheless viewed IP as an important tool for development. 39 Similarly, during early TRIPS waiver discussions, both Russia and El Salvador emphasized that “promoting and incentivizing innovation as a tool for boosting and accelerating development” was “a top national priority.” 40 As a result, El Salvador found it “difficult to reconcile” the waiver with the domestic development objectives that it had set as a country.” 41

Civil society organizations

Over 350 civil society groups, including access to medicines groups, HIV/AIDS organizations, global health and global justice alliances, and human rights groups, expressed strong support for the TRIPS waiver, with many further arguing that governments should view the waiver as a minimum first step to securing access to needed COVID-19 vaccines, therapeutics, and medical devices. Statements from these groups were often directly addressed to heads of WTO members, with requests that governments view the adoption of the waiver as an urgent matter. Four major rationales were advanced by these organizations: (1) the TRIPS waiver enables countries to overcome IP-based supply barriers that cannot be adequately addressed through voluntary or compulsory licensing; (2) the TRIPS waiver enables countries to uphold their human rights obligations; (3) the TRIPS waiver is a necessary but insufficient step toward achieving equitable access to health technologies during COVID-19; and (4) corporate profit should not be prioritized over equitable access. Below, each rationale is discussed in further detail.

- IP is a barrier to access that cannot be addressed by voluntary or compulsory licensing . Civil society organizations endorsed the view that IP obstructs the production and distribution of affordable COVID-19 health technologies. Many noted that relying solely on voluntary licensing is not a sufficient remedy, as historically it has “failed to leverage global expertise and capacity to scale up manufacturing and deliver equitable access.” 42 Furthermore, the existing compulsory licensing mechanism designed to lawfully circumvent these restrictions was seen to suffer from scaling issues. Many argued that countries are obliged to issue compulsory licenses on a country-by-country and product-by-product basis, and thus that the existing compulsory licensing system is ill-suited for rapid global distribution. It was asserted by many that addressing international access concerns through compulsory licenses “would create a monumental coordination crisis because of the possible need to initiate and win compulsory licensing proceedings in multiple jurisdictions.” 43 Groups highlighted that LMICs have been historically “discouraged from using compulsory licensing for access to medicines due to pressures from their trading partners and pharmaceutical corporations” and that the article 31bis compulsory licensing pathway has been successfully employed only once, to import patented pharmaceuticals to Rwanda. 44 The TRIPS waiver was promoted as a solution to overcoming these IP-related issues at a global scale necessary to addressing an international pandemic.

- A TRIPS waiver enables states to uphold their international human rights obligations . Many civil society organizations emphasized the role of a TRIPS waiver in ensuring equal access to critical health technologies consistent with the human rights to health, to receiving and imparting information, to education, to participating in cultural life, and to equally benefitting from scientific progress. In a letter signed by 107 groups, governments were urged to recognize the inequalities exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, with an emphasis on the resulting unequal access to vital technological knowledge among countries. 45 These groups emphasized the importance of ensuring that essential COVID-19 research is made available immediately and everywhere, and argued that “removing legal barriers to knowledge is… needed for the massive, urgent scale-up of vaccine production.” 46 Others echoed WHO Director-General Tedros Ghebreyesus’s 2021 statement that “profits and patents must come second to the human right to health” in supporting arguments that COVID-19 vaccines, as the “common property of humanity,” must be made available as a matter of human rights. 47 The role of the TRIPS waiver as a tool for redressing global inequalities in access to COVID-related health technologies was asserted in most statements.

- The TRIPS waiver is necessary but insufficient for securing equitable access . Several civil society organizations framed the TRIPS waiver as the necessary but insufficient first of a series of measures that governments must take to ensure equitable access to lifesaving COVID-19 health technologies. 48 In addition, these groups advocated for know-how and technology transfer from patent holders to manufacturers in the Global South, increased direct investment into the expansion of manufacturing capacity in the Global South, and equitable dose sharing from the Global North to the Global South. 49 After the release of the amended waiver in June 2022, over 200 civil society organizations expressed dissatisfaction with the draft ministerial decision and the insufficiency of its application solely to COVID-19 vaccines, its exclusion of some of the world’s largest producers of medical tools, and its restriction of “the free movement and rapid distribution of needed medical products.” 50

- Moral appeal: corporate profits should not be prioritized over equitable access . Many civil society organizations adopted the moral position that governments should not prioritize the financial needs of the pharmaceutical industry over the immediate health of humans in need. Emphasis was placed on the collective state responsibility for human life, as well as the priority of this responsibility over states’ competing responsibilities to honor corporate monopolies. 51

Research-based pharmaceutical companies

Approximately 48.5% of pharmaceutical companies expressed opposition to the proposed TRIPS waiver, either by directly authoring statements or endorsing statements authored by industry-wide associations. These included five companies (AstraZeneca, BioNTech, Janssen, Pfizer, and Sanofi) that are currently partnered with COVAX for the purpose of supplying vaccines to LMICs, as well as pharmaceutical manufacturing trade associations Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations, and European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations. Approximately 7.5% of manufacturers (Bharat Biotech, Biological E, CureVac, Gamaleya, and Moderna) released neutral statements about the TRIPS waiver, indicating a willingness to not enforce their own intellectual property rights but refraining from explicitly endorsing the waiver. The remaining 44% did not release statements about the TRIPS waiver.

The primary arguments advanced against the TRIPS waiver were that (1) a TRIPS waiver would not be effective in increasing global supplies since IP is not a barrier to access; (2) a TRIPS waiver would threaten innovation, thus reducing the pharmaceutical industry’s ability to produce lifesaving technologies; (3) a TRIPS waiver would undermine existing partnerships among manufacturers; and (4) a TRIPS waiver would not rapidly rectify vaccination deficits, which is the ultimate goal of the international COVID-19 response. These arguments are presented below.

- IP is not a barrier to access. Almost all pharmaceutical companies refuted the assertion that IP protection has limited access to patented COVID-19 health technologies throughout the pandemic. Instead, focus was placed on trade restrictions, distribution bottlenecks, and raw material scarcity. 52 Manufacturers emphasized the sufficiency of existing manufacturing capacity and supply chains to provide COVID-19 vaccines to the world’s population, stating that “in 2021, more than 40% of these [3 billion] doses are expected to go to middle- and low-income countries. We believe … that in the next 9 to 12 months, there will be more than enough vaccines produced.” 53 Given these assertions, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America and the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations argued that a TRIPS waiver would be not only unnecessary but harmful to existing manufacturer efforts to expand access through voluntary licensing and technology transfer agreements. 54

- A TRIPS waiver threatens innovation . Pharmaceutical manufacturers frequently expressed their opposition to the TRIPS waiver on grounds that waiving IP protection would threaten innovation. Premised on the assertion that IP protections enable innovators to earn the returns necessary to finance risky pharmaceutical research and development (R&D), manufacturers asserted that a TRIPS waiver would undermine ongoing efforts to develop health technologies for new COVID-19 variants. 55 Manufacturers also cited the proposed waiver’s broader deleterious effects on scientific innovation at large, with Pfizer’s chairman and CEO releasing a public letter expressing concern that a TRIPS waiver would disincentivize scientific investments to the particular detriment of small, investor-dependent biotech innovators. 56

- A TRIPS waiver would undermine existing voluntary licensing partnerships . Throughout the pandemic, manufacturers of patented COVID-19 vaccines have underscored their efforts to ensure expanded access by entering into voluntary licensing agreements with third-party manufacturers. In implementing a waiver that would enable countries to suddenly cease enforcing domestic intellectual property rights, manufacturers argued that WTO members risked placing these ongoing inter-manufacturer supply agreements at risk. 57 Two key rationales were presented to support the assertion that IP enforcement is a vital component to ongoing voluntary licensing agreements. First, manufacturers argued that voluntary licenses enable patent owners to carefully pick partner manufacturers that are best equipped to produce quality products. 58 Without such oversight in place, it was alleged that the safety and efficacy of produced vaccines would be threatened. 59 Second, manufacturers asserted that a TRIPS waiver would exacerbate raw material shortages, thus undermining ongoing partnerships, as “entities with little or no experience in manufacturing vaccines [would be] likely to chase the very raw materials that [current manufacturers] require to scale production.” 60

- A TRIPS waiver is not a sufficiently rapid solution for rectifying international vaccination deficits . Several manufacturers acknowledged the importance of equitable access to vaccines but maintained that the proposed TRIPS waiver would be unable to rapidly rectify existing vaccination deficits. Instead, they asserted that focus should be shifted toward enhancing voluntary technology transfer arrangements, increasing health infrastructure funding, and expanding educational programs to combat vaccine hesitancy. 61 For example, a statement by AstraZeneca’s executive vice president of Europe and Canada emphasized that “the TRIPS process is no quick fix and could take many months—far too late for millions of people in underserved communities”—and advocated for a suite of “urgent response” measures, including not-for-profit pricing commitments by manufacturers, expanded regional supply chains, and voluntary technology transfer agreements with domestic manufacturers in the Global South. 62

Stakeholder rationales align with historic divides on the relationship between IP and access to medicines

Among the 131 WTO members that expressed a definite position with respect to the TRIPS waiver, we found that approximately 73% support the waiver (with 65 of 96 supporters endorsing the waiver as co-sponsors). Over 350 civil society groups overwhelmingly aligned with those WTO members in support of the waiver. By contrast, approximately 86% (30 out of 35) pharmaceutical industry stakeholders who issued or endorsed statements regarding the TRIPS waiver uniformly aligned with those WTO members opposed to the waiver.

WTO members opposed to the TRIPS waiver shared overlapping arguments with pharmaceutical industry stakeholders more frequently than endorsing WTO members did with civil society organizations (see Tables 2 and and3). 3 ). The WTO members that were the most vocally opposed to the TRIPS waiver (the United Kingdom, European Union, and Switzerland) and whose arguments aligned most strongly with pharmaceutical industry stakeholders were also those members in which COVID-19 vaccine manufacturers (AstraZeneca, BioNTech/ Pfizer, and Moderna) maintain headquarters or major manufacturing facilities. By contrast, the WTO members that most frequently expressed support for the TRIPS waiver in alignment with civil society-backed rationales were those countries with large domestic generic manufacturing capacities (e.g., India) or that had previously considered or engaged in compulsory licensing for pharmaceuticals (e.g., South Africa, Malaysia, and Sri Lanka). This aligns with the view that in the context of the WTO, an institution primarily designed to facilitate the commercial exchange of goods and services between countries, many members’ decisions to support health-related proposals likely remain highly dependent on prevailing domestic economic priorities.

Comparison of dominant TRIPS waiver position rationales among supporting stakeholders

Comparison of dominant TRIPS waiver position rationales among opposing WTO members and pharmaceutical industry stakeholders

Notably, several dominant rationales offered by WTO members, pharmaceutical stakeholders, and civil society organizations reflect the same arguments raised during the HIV/AIDS crisis in the early 2000s surrounding the use of compulsory licenses to expand access to antiretrovirals. 63 At the time, pro-compulsory licensing advocates frequently appealed to states’ humanitarian obligations and emphasized the importance of protecting human lives over private profits, while pro-IP advocates rooted their position on grounds of recouping R&D costs, promoting innovation, and securing product quality. 64 The continued use of this language in the context of TRIPS waiver discussions—and the upending endorsement of compulsory licensing by TRIPS waiver opponents as a more feasible solution than the waiver—suggests that the relationship between IP and access to medicine remains highly contentious within the trade and health landscape despite the 2001 Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health. 65 Since the WTO operates as a consensus-based decision-making body, this continued division between members presents as a key policy obstacle for states seeking to leverage the international trade system to promote expanded access to health technologies within their domestic health systems.

The TRIPS waiver and human rights

Among all stakeholders, the importance of ensuring equitable access to COVID-19 health technologies has not been refuted. In TRIPS waiver discussions among WTO members, differences in vaccine prices and availability between high-income countries and LMICs were frequently highlighted by members as evidence of ongoing inequalities. For example, South Africa argued that it had been charged US$5.25 per dose for AstraZeneca’s vaccine while European Union members had been charged only US$3.50. 66 Several LMIC members also expressed frustration with the unavailability of vaccines for their own populations due to the bilateral supply deals negotiated in advance between high-income countries and manufacturers.

To varying degrees, all WTO members, civil society organizations, and pharmaceutical industry stakeholders that authored or endorsed statements related to the TRIPS waiver acknowledged the importance of rectifying the asymmetric distribution of COVID-19 vaccines between high-income countries and LMICs. However, only civil society organizations consistently framed this inequality in terms of explicit human rights considerations. Here, inequitable international COVID-19 vaccine deployment was frequently viewed as a violation of the human rights to health and to benefit from scientific progress, enshrined in articles 12 and 15 of the ICESCR. The TRIPS waiver was thus supported as an urgent measure explicitly required to rectify ongoing human rights violations. By contrast, WTO members largely refrained from employing human rights language during TRIPS waiver discussions, with the sole reference to article 12 of the ICESCR found in the preambular text of TRIPS waiver sponsors’ September 2021 position summary document. 67 WTO members opposed to the TRIPS waiver often couched their positions in terms of equitable vaccine access, citing either the independent or combined sufficiency of COVAX and inter-manufacturer voluntary licensing agreements in attaining this goal. Similarly, pharmaceutical manufacturers frequently underscored their post-scaling ability to supply vaccines to LMICs that were previously unable to secure doses at the beginning of the pandemic. Thus, while not always framed in terms of explicit human rights obligations, ensuring equitable international access to COVID-19 vaccines has been recognized as a desirable objective by TRIPS waiver proponents and opponents alike—with the efficacy of the proposed TRIPS waiver in successfully achieving this goal at issue.

Given members’ polarizing positions with respect to the TRIPS waiver and the WTO requirement that resolutions be passed through consensus, it is perhaps unsurprising that TRIPS waiver negotiations have struggled to advance. In an attempt to broker a compromise acceptable to all WTO members, the March 2022 TRIPS waiver solution proposed by the European Union, India, South Africa, and the United States sought to make the TRIPS waiver more palatable to opposing members while still providing members with a more streamlined alternative to the compulsory licensing system in articles 31 and 31 bis of the TRIPS Agreement. 68 Public responses to this proposal were largely critical. Civil society organizations decried the compromise as a partial measure incapable of meaningfully increasing access to COVID-19 health technologies and legally unprecedented in its narrow interpretation of the existing article 31 compulsory licensing regime. 69 Conversely, COVID-19 vaccine manufacturers emphasized the compromise’s lack of necessity given recent reports of vaccine overproduction and global demand reductions. 70 Comparable reactions were also elicited from these groups in response to the narrower June 2022 draft decision text. Notably, while civil society groups and pharmaceutical stakeholders alike demonstrated a strong reluctance to endorse compromises that deviated significantly from their original positions, the June 2022 compromise required many WTO members to endorse positions that they initially opposed. While this indicates that the rules-based international trading system remains capable of encouraging consensus-building among its members, the two years of debate preceding this decision suggest that trade-based public health measures are likely ill-suited as first-line responses to urgent and international public health crises.

Access to lifesaving health technologies, such as COVID-19 vaccines, remains starkly inequitable between countries. Responses by WTO members, civil society organizations, and pharmaceutical industry stakeholders to the proposed TRIPS waiver highlight universal acknowledgment of this unequal health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, where proponents view the TRIPS waiver as a necessary first step toward eliminating IP-driven barriers to access during the pandemic, opponents largely assert that the TRIPS waiver is a political distraction that is both unnecessary and incapable of rapidly expanding the supply of COVID-19 health technologies.

Discourse surrounding the TRIPS waiver suggests that the global community seems to be expressing similar IP and public health arguments as those advanced during the HIV/AIDS crisis. This underscores the continued lack of reliability that countries face when looking to the international trading system as a means to advance public health imperatives and improve access to lifesaving health products. It also suggests the need for deep structural change and how lessons learned are often forgotten.

As WTO members consider the adoption of an expanded TRIPS waiver, the COVID-19 pandemic continues to spread globally with new emerging variants. Without improved international coordination, transparency, and consideration for the health and human rights of all global citizens, states risk remaining ill-prepared for future pandemics and global emergencies. Governments must therefore continue to collectively strive toward the development of equitable solutions so that meaningful progress can be made to improve global access to essential health products. Without decisive action, countries risk being unprepared for future public health crises and continuing to propagate patterns of health inequity.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the feedback received from Sharifah Sekalala, Katrina Perhudoff, Lisa Forman, and others during the Connaught Global Challenge Research Program’s “Advancing Rights-Based Access to COVID-19 Vaccines as Part of Universal Health Coverage” paper development workshop on May 17, 2022.

We thank the Connaught Global Challenge Award for funding for this research through the “Advancing Anti-Corruption, Transparency and Accountability Mechanisms to Tackle Corruption in the Pharmaceutical System” and the “Advancing Rights-Based Access to COVID-19 Vaccines as Part of Universal Health Coverage” grants.

Ethics approval

Since this research exclusively employed data obtained from public documents, no ethics approval was required.

WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION

Home | About WTO | News & events | Trade topics | WTO membership | Documents & resources | External relations

Contact us | Site map | A-Z | Search

español français

Discussion on the extension of COVID-19 IP waiver

At MC12, trade ministers adopted the Ministerial Decision on the TRIPS Agreement, which gives members greater scope to take direct action to diversify production of COVID-19 vaccines and to override the exclusive effect of patents through a targeted waiver over the next five years. It addresses specific problems identified during the pandemic and aims to help diversify vaccine production capacity. It also contains a commitment that no later than six months from the date of the decision (17 June), members will decide on its possible extension to cover the production and supply of COVID-19 diagnostics and therapeutics.

Many members took the floor to welcome the successful outcome at MC12, saying it proved that WTO members can put aside differences and work together to respond to the most urgent health challenges.

A group of developing members who support an extension of the waiver to cover COVID-19 diagnostics and therapeutics circulated a proposal at the meeting including an indicative timeline for the TRIPS Council's next steps in this regard.

These members argued that the waiver on COVID-19 vaccines falls short of their expectation and is not enough to help developing countries comprehensively address current and future health challenges. Equitable access to therapeutics and diagnostics, as pointed out by the World Health Organization (WHO), is critical in helping detect new cases and new variants. They said this waiver extension needs to be discussed with a sense of urgency given the fact that many least developed countries (LDCs) lack access to life-saving drugs and testing therapeutics.

Many developing countries supported the initiative. They highlighted the joint statement made by the three Director Generals of the WHO, the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) and the WTO in June 2021 reaffirming their commitment to intensifying cooperation in support of access to medical technologies worldwide to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic, including vaccines, therapeutics and diagnostics. There was also a shared view that the negotiation process for the waiver extension should be open, inclusive and transparent.

Other members cautioned that more time was needed to conduct domestic consultations on a possible extension of the waiver to therapeutics and diagnostics. Some members also flagged the importance of an evidence-based negotiation as there was no evidence that intellectual property did indeed constitute a barrier to accessing COVID-19 vaccines. Some also reiterated the need for members to fully make use of all the flexibilities that already exist in the TRIPS Agreement (including compulsory licensing) before requesting new flexibilities.

The chair, Ambassador Lansana Gberie (Sierra Leone), asked members that were ready to engage to commence discussing this matter in various configurations. He encouraged members to individually report on progress to the General Council meeting on 25-26 July while some members may need more time to deliberate on the matter, he noted. The chair will inform members how best to structure discussions on this matter going forward, he added.

Members also agreed to continue exchanges under the agenda item of IP and COVID-19 so that the TRIPS Council can keep abreast of new IP measures in relation to COVID-19 and share relevant experience. The Council also decided that the Secretariat will continue compiling and updating all COVID-related IP measures in its document “ COVID-19: Measures regarding Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights ” to serve as the basis for members' exchanges.

Members noted that this exercise is also in line with the Ministerial Declaration on the WTO Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic and Preparedness for Future Pandemics which provides for ongoing analysis of lessons learned and challenges experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic within the relevant WTO bodies.

IP and innovation: IP licensing opportunities

Under an item on IP and Innovation which had been requested by Australia, Canada, the European Union, Hong Kong China, Japan, Singapore, Switzerland, Chinese Taipei, the United Kingdom and the United States, the co-sponsors presented their new submission with a focus on IP licensing opportunities ( IP/C/W/691 , circulated on 23 June).

The co-sponsors highlighted several major ways owners of IP assets can secure a broader reach for their products and services through licensing agreements, which enable IP owners to allow the licensee to make or sell the invention during the licence period. This includes licensing of patents, copyright, trademarks and know-how.

The proponents shared experiences on how to apply different licensing models and build up a friendly ecosystem to foster IP trading. To overcome the knowledge gap and complexity of implementing IP licensing, these countries have developed various toolkits to provide training, online guidelines, contract templates, legal services and dispute settlement so that small businesses and individuals can effectively participate in IP partnerships.

Members welcomed the discussion on IP innovation and IP licensing, with some sharing their domestic practices. WIPO introduced its recent activities in support of IP licensing, including the establishment of an IP and innovation ecosystems sector, the work of the WIPO arbitration and mediation centre, and guidance to help start-ups develop their IP strategy.

Non-violation and situation complaints

WTO members welcomed the decision adopted at MC12 to extend the moratorium on non-violation and situation complaints (NVSCs) under the TRIPS Agreement until the next Ministerial Conference (MC13). The decision tasked members to continue examining possible scope and modalities for NVSCs and to make recommendations to MC13.

This concerns the longstanding issue of whether members should have the right to bring dispute cases to the WTO if they consider that another member's action or a specific situation has deprived them of an expected benefit under the TRIPS Agreement, even if no specific TRIPS obligation has been violated.