- Home Kāinga

- Our Story Ngā Kōrero

- Our Tours Ngā Haerenga

- Wellington Museum Te Waka Huia o Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho

- Space Place Te Ara Whānui ki te Rangi

- Nairn Street Cottage

- Cable Car Museum

- Careers Umanga

- What’s On Ngā Kaupapa Whakatairanga

- Museum Blog

- Our Venues Ngā Wāhi

- Venues at Wellington Museum Ngā Wāhi i Te Waka Huia o Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho

- Venues at Space Place Ngā Wāhi i Te Ara Whānui ki te Rangi

- Birthday Parties Ngā Pāti Rā Whānau

- Recommended Caterers Ētahi Kaitaka Kai

- Education Blog Rangitaki Mātauranga

- Space Place

- Wellington Museum

- Space Place Wāhi Haumaru

- Venues at Space Place Ngā Wāhi i Te Wāhi Haumaru

- Support Us Tautoko

- Museum Blog Te Kāpata Te Curio

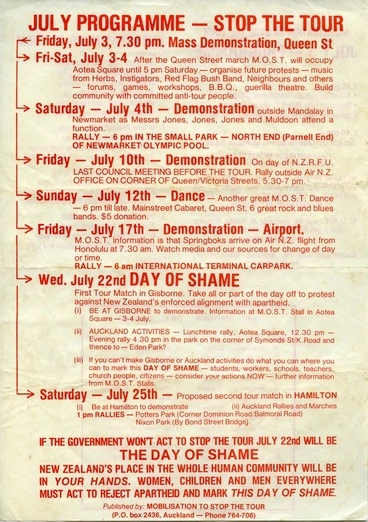

Remembering the 81′ Springbok Tour

40 years on, we look back and talk to two Wellington residents who remember those turbulent times.

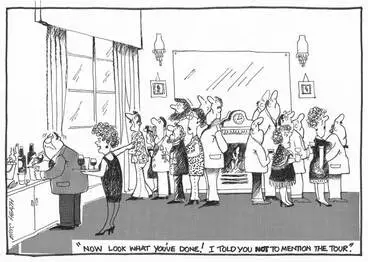

“All for the sake of a Rugby game. Doesn’t make sense does it?” – Liz Roberts

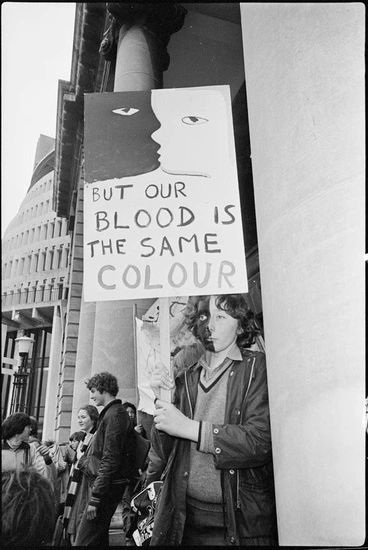

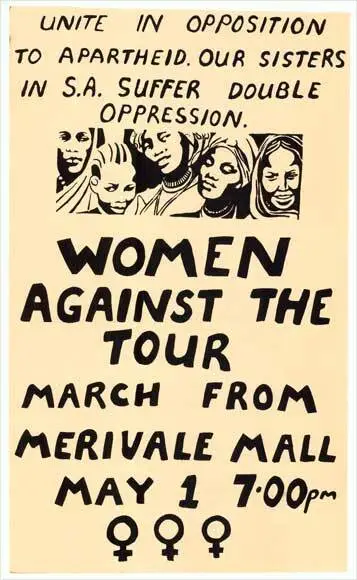

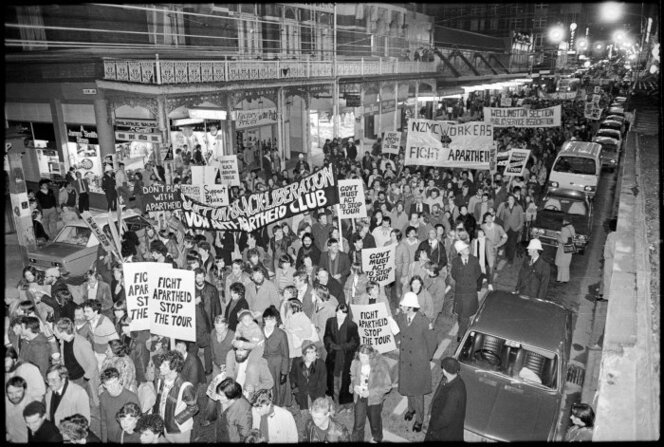

During the winter of 1981, violent clashes between rugby supporters, protesters and the police erupted all over Aotearoa in one of our country’s most tumultuous periods. The Springbok rugby tour brought us to the brink of civil war, as many protested the racial segregation of Apartheid South Africa and made links to racism at home.

On the 29th of July, 1981, protesters opposing the Springbok Tour were met by baton-wielding police trying to stop them marching up Molesworth St to the home of South Africa’s Consul to New Zealand.

This was the first time police had used batons against protestors, and the violence horrified many New Zealanders. Former Prime Minister Norman Kirk’s prediction eight years earlier that a tour would result in the ‘greatest eruption of violence this country has ever known’ seemed to ring true.

Wearing helmets like this one, 7000 protesters gathered in central Wellington and around Athletic Park on 29th of August 1981 to stop pro-tour supporters from gaining access to the second test match. Once again the police intervened, this time using long batons, with many protesters injured as a result. This helmet was worn by Anne Bogle during other anti-tour protests.

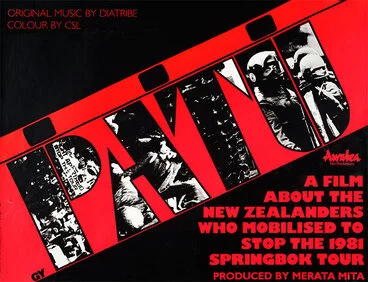

The Merata Mita Estate permitted us to use the Wellington footage from PATU! (1983) – the powerful documentary directed by Merata Mita which shows the harrowing events of the 1981 Springbok Tour.

Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision meticulously restored and preserved the original documentary for the 40th anniversary. With their approval, we were able to use their newly restored and remastered version for these videos.

Liz Roberts lived on Te Wharepōuri Street in Berhampore, close to Athletic Park, and recalls the events of the 2nd Test on August 29th, 1981, where she saw protesters clash with Police on her street.

Anne Bogle was a young Victoria University student studying Law and History in 1981 – and attended a number of Anti-Tour protests in Wellington – she took part in the protest group that blocked the Wellington Motorway on July 25th and the infamous Molesworth Street incident a few days later on July 29th. The protester helmet she used during the anti-tour demonstrations is currently displayed at Wellington Museum.

Thank you to the Merata Mita Estate for their permission to use parts of the film and also to Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision for their great mahi on the preservation and restoration of this important piece of film taonga .

Also thank you to Anne Bogle and Liz Roberts for sharing their stories.

Pin It on Pinterest

- Join - It's Free

1981 Springbok Tour

« Back to Projects Dashboard

Project Tags

- sports people

- sports team

Related Projects

- New Zealand Portal

- New Zealand Premiers, Prime Ministers and Politicians

- Notable New Zealanders

- South African Rugby Tours

Top Surnames

The 1981 South African rugby tour (known in New Zealand as the Springbok Tour, and in South Africa as the Rebel Tour) polarised opinions and inspired widespread protests across New Zealand.

In the 1960s and 70s, many New Zealanders had come to believe that playing sport with South Africa condoned its racist apartheid system. Apartheid excluded non-white players, and therefore Maori, from touring there. This made the 1981 tour to New Zeeland among the most divisive events in New Zealand’s history.

By this time, Errol Tobias had become the first Springbok of colour, and he was included in the squad, but despite playing well there, he was excluded from the tests by the Springbok administrators on tour, who were resistant to having him as a Springbok because of his race. Ironically, Tobias was also targeted by anti-apartheid protesters, who accused him of being a sell-out and an Uncle Tom. In fact, he wasn't either. He had proved himself on the field throughout his career to that point, and been selected on merit.

Springboks - Outgoing squad

- Jacobus Johannes Beck

- Hendrik Johannes Bekker

- Daniel Sarel Botha

- Matthys Boshoff Burger

- Captain Wynand Claasen

- Robert James Cockrell

- Willem Du Plessis

- Carel Johan Du Plessis

- Pieter Gerhardus Du Toit

- Schalk Burger Geldenhuys

- Johannes Servaas Germishuys

- Johan Wilhelm Heunis

- Eben-haéser Jansen

- Wilhelm Julius Heinrich Kahts

- Eduard Friedrich Wilhelm Krantz

- Robert James Louw

- Louis Christiaan Moolman

- Raymond Herman Mordt

- Ockert Wessel Oosthuizen

- Zacharias Mattheus Johannes Pienaar

- Shaun Albert Povey

- David Jacobus Serfontein

- Marthinus Theunis Steyn Stofberg

- Henning Jonathan Van Aswegen

- Phillip Rudolph Van der Merwe

- Gabriël Pieter Visagie

- Johann De Villiers Visser

- Barend Johannes Wolmarans

- Errol Tobias

- Captain Andrew Grant "Andy" Dalton

- Murray Mexted

- Billy Bush. captain of the Maori team

Add profiles to this project

Add collaborators to this project.

- © 2024 Geni.com

- US State Privacy Notice

- Code of Conduct

- World Family Tree

Weekend Rewind: The 1981 Springbok Tour, 35 years on

Share this article

Anti Springbok tour protesters at Auckland International Airport protesting the arrival of the South African rugby team in 1981. Photo / File, NZ Herald Archive

On July 19 1981, the South African rugby team arrived in New Zealand, dividing the nation, and sparking 56 days of major civil unrest (along with years of subsequent fallout.) More than 200 demonstrations took place throughout the country, with over 150,000 people taking part. Clashes between tour supporters and protesters, and protesters and police, became increasingly frequent and violent. Not surprisingly, many of our film and television makers felt it important to document and interpret events.

Directed by Merata Mita, Patu! Is both a landmark in New Zealand's film history and a startling record of the tour. Made on a shoestring budget, with the aid of several volunteer camera people (among them Roger Donaldson), it still holds up as a standout piece of activist filmmaking. The documentary profiles the anti-tour campaign, capturing highly charged footage of the clashes. While filming, stock was shifted around and, at times taken out of, the country, as the production team went into hiding to prevent the police from hijacking the editing process.

Watch Patu! here:

Made for the 25th anniversary of the tour in 2006, the documentary Try Revolution examines the impact of the tour in South Africa, showing how events in New Zealand poured shame on the apartheid regime, and helped provoke democratic change. As quoted from Archbishop Desmond Tutu: "You really can't even compute its value, it said the world has not forgotten us, we are not alone."

Watch an excerpt from Try Revolution here:

Landmark documentary series Revolution mapped the social and economic changes in 1980s New Zealand. Touching on the political ramifications of the tour, it highlights then Prime Minister Robert Muldoon's refusal to intervene in its go-ahead, and the effects of his decision on the National Party. Writer CK Stead reflects on the tension of the on-field protest that stopped the tour's Hamilton game.

See part two of Revolution for coverage of the tour:

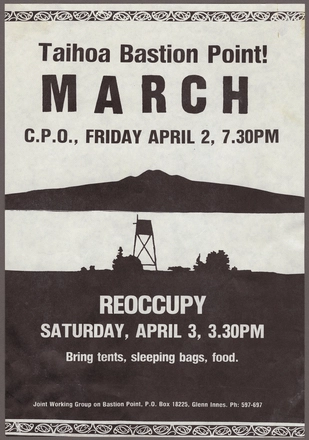

1982 one-off drama The Protesters explores issues surrounding race and land ownership in the aftermath of both the tour and the occupation of Bastion Point. Starring Billy T James, Jim Moriarty and Merata Mita, it also features early roles from Robert Rakete and former newsreader Joanna Paul. Capturing a mood of division and uncertainty, it's a telling representation of the post-tour climate.

Watch The Protesters here:

Made in 2011, TV movie Rage is set during the tour, telling the story of a protester who falls in love with an undercover policewoman. The script was written by noted cartoonist and columnist Tom Scott - a protester during the tour - and his brother-in-law Grant O'Fee, a detective sergeant in Wellington at the time.

Watch an excerpt from Rage here:

Made by Ric Salizzo and John Kirwan in 1992, All Blacks for Africa - A Black and White Issue follows the All Blacks on their first post-apartheid visit to South Africa. Between scenery shots and match highlights, players past and present reflect on politics and sport - amongst them ex-AB Ken Gray, who refused to tour the republic in 1970 and joined anti-tour protesters in 1981.

Watch All Blacks for Africa - A Black and White Issue here:

You can see more Springbok Tour footage here, in NZ On Screen's Spotlight Collection.

Latest from Entertainment

Baby Reindeer: What to know about the true-ish Netflix hit

New York Times: The mini-series has viewers wondering how much of it is real.

Family and friends pay tribute to Herbs frontman Willie Hona

'Don’t say that s*** again': Tom Brady's awkward hot mic moment during roast

Kiwi reggae legend Willie Hona of Herbs has died

The dog that caught a taxi

- Access Statement

- Community Archive

- Family History

Sir Michael Fowler

- Molesworth Street

- Related Items (9)

- Related Items (5)

- Related Items

- Property Search

- Accessing our collections

- Archives online user guide

"I hope that common sense will prevail." – Sir Michael Fowler, Mayor of Wellington, 28th August 1981 From 22 July – 12 September 1981 the South African Rugby Union team (known as the Springboks) toured New Zealand playing 14 games. Due to the South African governments policy of apartheid, the tour was marred by protests and police violence. The All Blacks and the Springboks had been fierce rivals since their first face-off at Athletic Park in 1928, and rugby had since become New Zealand’s national identity. But at the same time, South Africa’s system of racial apartheid had grown unacceptable to many people in New Zealand and overseas. Wellington was a focal point for much of the anti-tour movement during 1981 tour. The Mayor and many of the City Councillors came out against the tour, and several attempts were made by Council to prevent a test match in the City. Protesters clashed with police during a protest on Molesworth Street leaving many battered and bloody. When they next met outside Athletic Park on the day of the test, the protesters came prepared with helmets and shields. The Springboks left New Zealand following their final game in Auckland and would not return until 1994 and the dismantling of apartheid. Linked below are photos of anti-tour posters and pamphlets taken by the City Photographer, as well as a considerable amount of correspondence to and from Mayor Fowler via the Town Clerk's Department. The featured minute book contains City Council meetings related to the tour on pages 207-208 (images 286-287) and 221-222 (images 300-301).

Copy: Abortion, Apartheid, Unions, Nuclear (posters, handouts, protests)

Notice of motion: Springbok Rugby Tour, REDACTED

Volume 102, REDACTED, Minutes of meetings of the Wellington City Council 5 Jun 1981 to 11 Nov 1981

- You are here

- Everything Explained.Today

- A-Z Contents

- 1981 South Africa rugby union tour of New Zealand and the United States

1981 South Africa rugby union tour of New Zealand and the United States explained

The 1981 South African rugby tour (known in New Zealand as the Springbok Tour , and in South Africa as the Rebel Tour ) polarised opinions and inspired widespread protests across New Zealand. The controversy also extended to the United States, where the South African rugby team continued their tour after departing New Zealand.

Apartheid had made South Africa an international pariah , and other countries were strongly discouraged from having sporting contacts with it. Rugby union was (and is) an extremely popular sport in New Zealand, and the South African team known as the Springboks were considered to be New Zealand's most formidable opponents. Therefore, there was a major split in opinion in New Zealand as to whether politics should influence sport in this way and whether the Springboks should be allowed to tour.

Despite the controversy, the New Zealand Rugby Union decided to proceed with the tour. The government of Prime Minister Robert Muldoon was called on to ban it, but decided that commitments under the Gleneagles Agreement did not require the government to prevent the tour, and decided not to interfere due to their public position of "no politics in sport". Major protests ensued, aiming to make clear many New Zealanders' opposition to apartheid and, if possible, to stop the matches taking place. This was successful at two games, but also had the effect of creating a law and order issue: whether a group of protesters could be allowed to prevent a lawful game taking place.

The dispute was similar to that involving Peter Hain in the United Kingdom in the early 1970s, when Hain's Stop the Tour campaign clashed with the more conservative 'Freedom Under Law' movement championed by barrister Francis Bennion . The allegedly excessive police response to the protests also became a focus of controversy. Although the protests were among the most intense in New Zealand's recent history, no deaths or serious injuries resulted.

After the tour, no official sporting contact took place between New Zealand and South Africa until the early 1990s, after apartheid had been abolished. The tour has been said to have led to a decline in the popularity of Rugby Union in New Zealand, until the 1987 Rugby World Cup .

The Springboks and New Zealand's national rugby team, the All Blacks , have a long tradition of intense and friendly sporting rivalry.

From 1948 to 1969, the South African apartheid regime affected team selection for the All Blacks, with selectors passing over Māori players for some All Black tours to South Africa.

Opposition to sending race -based teams to South Africa grew throughout the 1950s and 1960s, and prior to the All Blacks' tour of South Africa in 1960, 150,000 New Zealanders – 6.25% of the country's population at that time – signed a petition supporting a policy of "No Maoris, No Tour". Despite this, the tour still happened, and in 1969, Halt All Racist Tours (HART) was formed.

During the 1970s, public protests and political pressure forced on the New Zealand Rugby Union (NZRFU) the choice of either fielding a team not selected by race, or not touring South Africa: after South African rugby authorities continued to select Springbok players by race, the Norman Kirk Labour Government barred the Springboks from touring New Zealand during 1973. In response, the NZRFU protested about the involvement of "politics in sport".

On 28 March 1976, the final game of ex-All Black Fergie McCormick was played at Lancaster Park in Christchurch, to which two Springbok players had been invited. Ten days before the game, protesters had written "WELCOME TO RACIST GAME" in 20-foot high letters on the pitch using weed-killer. [1] [2] [3]

The All Blacks toured South Africa with the blessing of the newly elected New Zealand Prime Minister, Robert Muldoon . In response to this, twenty-five African nations boycotted the 1976 Summer Olympics in Montreal, stating that in their view, the All Blacks tour gave tacit support to the apartheid regime in South Africa: the IOC declined to ban New Zealand from the Olympics on the grounds that rugby union was no longer an Olympic sport.

The 1976 tour attracted several anti-apartheid protests in New Zealand, including one on 28 May 1976 in Cathedral Square, Christchurch which attracted 1000–1500 people and included guerrilla theatre. [4] [5] Protesters also attempted to disrupt television coverage of the first test by vandalising the Makara Hill microwave station in Wellington, which was responsible for relaying programming in and out of TV One 's Avalon studios. [6]

The 1976 tour contributed to the creation of the Gleneagles Agreement , that was adopted by the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in 1977.

Tour of New Zealand

the urgent duty of each of their Governments vigorously to combat the evil of apartheid by withholding any form of support for, and by taking every practical step to discourage contact or competition by their nationals with sporting organisations, teams or sportsmen from South Africa or from any other country where sports are organised on the basis of race, colour or ethnic origin.

Despite this, Muldoon also argued that New Zealand was a free and democratic country, and that "politics should stay out of sport." In the years following the Gleneagles Agreement, it seemed that New Zealand government members did not feel bound to the Gleneagles agreement, and disregarded it. However, some historians claim that, "'the [Gleneagles] agreement remained vague enough to avoid the New Zealand government from having to use coercive powers such as withdrawing visas and passports."' [8] This means Muldoon's government technically wasn't bound to the agreement to the extent it outwardly appeared to the public. In addition to this, Ben Couch , who was the minister for Maori development at the time, stated, 'I believe that the Gleneagles agreement has been forced upon us by people who do not have the same kind of democracy that we have.' [9]

Muldoon made some effort to discourage the tour and stated that he could see ‘nothing but trouble coming from this.’ [10] ‘ A Springbok tour would dash to the ground all that has been achieved as a result of international acceptance ,' wrote deputy Prime Minister Brian Talboys to the chairman of the NZRFU in a further attempt to discourage the tour, [the tour] may affect the harmonious development of the Commonwealth and international sport .'

Some rugby supporters echoed the separation of politics and sport, [11] [12] while other rugby supporters argued that if the tour were cancelled, there would be no reporting of the widespread criticism of apartheid in New Zealand in the controlled South African media.

Muldoon's critics felt that he allowed the tour in order for his National Party to secure the votes of rural and provincial conservatives in the general election later in the year, which Muldoon won. [13] Along with Muldoon's policy of ‘leaving sporting contacts to sporting bodies,’ Muldoon also held the opinion that the disruption and division of New Zealand was not caused by the NZFRU, nor the Springboks, but the anti-tour protesters themselves. [14] This argument was vehemently refuted by anti-tour voices, political activist Tom Newnham claimed that the government enabled ‘the greatest breakdown in law and order [New Zealand] has ever witnessed.’ [15]

The ensuing public protests polarised New Zealand: [13] while rugby fans filled the football grounds, protest crowds filled the surrounding streets, and on one occasion succeeded in invading the pitch and stopping the game.

To begin with, the anti-tour movement was committed to non-violent civil disobedience , demonstrations and direct action . As protection for the Springboks, the police created two special riot squads, the Red and Blue Squads. These police were, controversially, the first in New Zealand to be issued with visored riot helmets and long batons (more commonly the side-handle baton). Some protesters were intimidated and interpreted this initial police response as overkill and heavy-handed tactics. After early disruptions, police began to require that all spectators assemble in sports grounds at least an hour before kick-off. While the protests were meant to be largely peaceful resistance to the Springbok tour, quite often, there were 'violent confrontations with rugby supporters and specially trained riot police.' [16]

At Gisborne on the day before the match anti-tour activists, including Mereana Pitman, gained access to the pitch with a vehicle and tipped broken glass on the pitch. [17] On 22 July, [18] protesters managed to break through a fence, but quick action by spectators and ground security prevented the game being disrupted. Some protesters were beaten by police. From the very first match of the tour in Gisborne, protester tension levels ran high, and one protester, cartoonist Murray Ball , who was the son of an All Black, recalled that it ‘was strange for New Zealanders to feel so aggressive towards other New Zealanders’ and that he was 'scared as hell' when he came up against pro-tour defenders. [17]

Hamilton: Game cancelled

At Rugby Park, Hamilton (the site of today's Waikato Stadium ), on 25 July, [18] about 350 protesters invaded the pitch after pulling down a fence. The police arrested about 50 of them over a period of an hour, but were concerned that they could not control the rugby crowd, who were throwing bottles and other objects at the protesters. [19] Following reports that a stolen light plane (piloted by Pat McQuarrie) was approaching the stadium, police cancelled the match. [19]

The protesters were ushered from the ground and were advised by protest marshals to remove any anti-tour insignia from their attire, with enraged rugby spectators lashing out at them. Gangs of rugby supporters waited outside Hamilton police station for arrested protesters to be processed and released, and assaulted some protesters making their way into Victoria Street. [20] There are many reports from protesters feeling unsafe during this protest, ‘It was terrifying, I don’t know how big the crowd was, but they were clearly furious…The police looked vulnerable as they spread out around the whole ground,’ [21] recollects one protester who was at the Hamilton Game where a conflict between those for and against the tour broke out.

Wellington: Molesworth Street protest

The aftermath of the Hamilton game, followed by the bloody batoning of marchers in Wellington 's Molesworth Street in the following week, in which police batoned bare-headed protesters, led to the radicalisation of the protest movement. There are many instances where the protesters had to fear for their safety, especially considering the violence that began on Molesworth Street, where police are said to have “behaved rather too similarly to South African police,'' according to Tom Newnham . [22] Former police officer, Ross Muerant , who was pro-tour, speaks of the Molesworth St protest: "The protestors, who so obviously lacked self-control, were that evening privy to a classic display of discipline." [23] This perspective of the police tactics has severe opposition from anti-tour activists, with claims that protesters were 'savagely attacked by police,' and that ‘police provoked violence.' While Newnham's claims that the violence towards protesters from police was unjustified was likely true in his experience, Muerant maintains that there were protesters who intended to inflict "serious injury or disfigurement" on the police. [23]

Because of this, many protesters began to wear motorcycle or bicycle helmet s to protect themselves from batons and head injury . [24] [25]

The authorities strengthened security at public facilities after protesters disrupted telecommunications by damaging a waveguide on a microwave repeater , disrupting telephone and data services, though TV transmissions continued as they were carried by a separate waveguide on the tower. [26] Army engineers were deployed, and the remaining grounds were surrounded with razor wire and shipping container barricades to decrease the chances of another pitch invasion. At Eden Park, an emergency escape route was constructed from the visitors' changing rooms for use if the stadium was overrun by protesters. Crowds of anti-tour protesters stood outside as the police were overwhelmed but the hundreds of police still managed to prevent the protesters from entering the stadium. [27]

Christchurch

At Lancaster Park , Christchurch, on 15 August, [18] some protesters managed to break through a security cordon and a number invaded the pitch. They were quickly removed and forcibly ejected from the stadium by security staff and spectators. A large demonstration managed to occupy the street adjacent to the ground and confront the riot police. [28] Spectators were kept in the ground until the protesters dispersed.

Auckland: plane invasion

A low-flying Cessna 172 piloted by Marx Jones and Grant Cole disrupted the final test at Eden Park , Auckland , on 12 September [18] by dropping flour-bombs on the pitch. In spite of the bombing, the game continued. [29] "Patches" of criminal gangs, such as traditional rivals Black Power and the Mongrel Mob , were also evident (The Black Power were Muldoon supporters [30] ). Footage was shown of the Clowns Incident , where police were shown beating unarmed clown s with batons. [31] The same day in Warkworth, Dunedin and Timaru protesters stormed the local TV transmitters and shut off coverage of the Auckland game. [32]

The protest movement

Some of the protest had the dual purpose of linking racial discrimination against Māori in New Zealand to apartheid in South Africa. Some of the protesters, particularly young Māori, felt frustrated by the image of New Zealand as a paradise for racial unity. [12] Many opponents of racism in New Zealand in the early 1980s saw it as useful to use the protests against South Africa as a vehicle for wider social action. However, some Maori supported the tour and attended games. John Minto , the national organizer for HART , thought that the tour "stimulate[d] the whole debate about racism, and the place of Maori in our community." [33] Political activist Tom Newnham’s opinion echoes that of Minto’s, albeit considerably more radical, stating that "we are basically the same as white South Africans, just as racist." [34] Some of those protesting racism in South Africa felt inclined to reflect on the racial divide in their own country, before condemning another – part-maori rugby spectator Kevin Taylor did not join the protests because he ‘wanted New Zealand to fix its own issues before New Zealanders started telling other countries how to fix their problems.’ [35]

Tour of the United States

With the American leg of the tour following directly after the events of New Zealand, further protests and clashes with police were expected. Threats of riots caused city officials in Los Angeles, Chicago, New York City and Rochester to withdraw their previous authorisation for the Springboks to play in their cities.

The Springboks' match against the Midwest All Stars team had originally been intended to be played in Chicago. Following the anti-apartheid protests, it was secretly rescheduled to the mid morning of Saturday 19 September at Roosevelt Park in Racine, Wisconsin . The clandestine strategy seemingly worked as around 500 spectators gathered to watch the match. Late in the game, however, a small number of protesters arrived to disrupt proceedings and two were arrested after a brief altercation broke out on the field.

Albany: pipe bomb

The cancelled New York City match against the Eastern All Stars was moved upstate to Albany . The long serving Mayor of Albany, Erastus Corning, maintained that there was a right of peaceful assembly to "publicly espouse an unpopular cause," despite his own stated view that "I abhor everything about apartheid".

Governor Hugh Carey argued that the event should be barred as the anti-apartheid demonstrators presented an "imminent danger of riot", but a Federal court ruling allowing the game to be played was upheld in the United States Court of Appeals . A further appeal to Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall was also overruled on the grounds of free speech .

The match went ahead with around a thousand demonstrators (including Pete Seeger ) corralled 100 yards away from the field of play, which was surrounded by the police. No violence occurred at the game but a pipe bomb was set off in the early morning outside the headquarters of the Eastern Rugby Union resulting in damage to the building estimated at $50,000. No one was injured.

The final match of the tour, against the United States national team , took place in secret at Glenville in upstate New York. The thirty spectators recorded at the match is the lowest ever attendance for an international rugby match.

The matches

In new zealand, in united states, touring party.

- Manager: Johan Claassen Assistant Manager: Abe Williams

- Coach: Nelie Smith ( Free State )

- Captain: Wynand Claassen

The Muldoon government was re-elected in the 1981 election losing three seats to leave it with a majority of one.

The NZRU constitution contained much high-minded wording about promoting the image of rugby and New Zealand, and generally being a benefit to society. In 1985, the NZRU proposed an All Black tour of South Africa: two lawyers successfully sued it, claiming such a tour would breach its constitution. A High Court injunction by Justice Casey saw the tour cancelled. [40] [41]

Afterwards, the All Blacks would not tour South Africa until after the fall of the apartheid regime, with the next official tour in 1992. After the 1985 tour was cancelled, an unofficial tour took place a year later by a team that included 28 out of the 30 All Blacks selected for the 1985 tour, known as the New Zealand Cavaliers , a team that was often advertised in South Africa as the All Blacks and/or depicted with the Silver Fern.

The role of the police also became more controversial as a result of the tour.

After the All Blacks won the 1987 Rugby World Cup , rugby union was once again the dominant sport – in both spectator and participant numbers – in New Zealand. [42]

In New Zealand culture

- Prominent artist Ralph Hotere painted a Black Union Jack series of paintings in protest against the tour.

- Merata Mita 's documentary film Patu! tells the tale of the tour from a left-wing perspective. [43]

- Music popularly associated with the tour included the punk band RIOT 111 , and the songs "Riot Squad" by the Newmatics and "There Is No Depression in New Zealand" by Blam Blam Blam . [44]

- Ross Meurant , commander of the police " Red Squad ", published Red Squad Story in 1982, giving a conservative view.

- The TVNZ 1980s police drama Mortimer's Patch included a flashback episode of the (younger) main character's tour police duties

- In 1984 Geoff Chapple wrote the book 1981: The Tour , chronicling the events from the protesters' perspective.

- In 1999 Glenn Wood's biography Cop Out covered the tour from the perspective of a frontline policeman.

- David Hill's book The Name of the Game is the story of a schoolboy's personal struggles during the tour.

- Tom Newnham 's book By Batons And Barbed Wire is one of the largest collections of photos and general information of the protest movement during the tour. (hardback). (paperback)

- The documentary 1981: A Country at War chronicled the tour from various perspectives. [45]

- Te Papa has objects related to the tour including images, helmets [46] [47] and an entrance ticket. [48] The exhibition Slice of Heaven: 20th Century Aotearoa has a section about the tour. [49]

- Rage , a dramatisation of the tour by Tom Scott , was filmed in mid-2011 [50] [51] and was broadcast on TV One on 4 September 2011. [52]

- The Engine Room , a play by Ralph McCubbin Howell , opened at BATS Theatre in Wellington on 27 September 2011. It contrasts the stories and viewpoints of John Key and Helen Clark during the tour and the 2008 general election .

- The second series of the television show Westside takes place during the events of the tour and portrays the main characters' involvement in several of the major incidents.

- 1971 South Africa rugby union tour of Australia

- History of South Africa in the apartheid era

- Robert Muldoon Ces Blazey New Zealand Cavaliers

- Politics and sports

- Sporting boycott of South Africa

Bibliography

- Book: Cameron, Don. 1981. Barbed Wire Boks. Rugby Press Ltd. Auckland, New Zealand. 978-0-908630-05-9 .

- Book: Chapple, Geoff . 1984 . 1981: The Tour . A H & A W Reed . Wellington . 978-0-589-01534-3 .

- Book: Newnham, Tom. 1981. By Batons and Barbed Wire. Real Pictures Ltd. New Zealand. 978-0-473-00112-4 .

- Book: Richards, Trevor. 1999. Dancing on Our Bones: New Zealand, South Africa, Rugby and Racism . Bridget Williams Books . Wellington, New Zealand. 1-877-242-004 .

External links

- Posters at Christchurch City Libraries

- Images of the events surrounding the Springbok Tour in the collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

- Online account

- A time line and references

- The 1981 Springbok Tour

- The 1981 Springbok Tour, including history, images and video (NZHistory)

- Letters solicited from the New Zealand public after the 1981 Springbok Tour

Notes and References

- Web site: Say it in acid . 2 March 2023 . paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- News: 29 March 1976 . Message with a difference . The Press .

- Web site: WELCOME TO RACIST GAME . 2 March 2023 . paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- Web site: Rally in Cathedral square . 2 March 2023 . paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- News: 29 May 1976 . 1500 in City Protest . 15 . Christchurch Star.

- News: 26 July 1976 . Saboteurs try to cut rugby TV coverage . 1 . .

- Web site: When talk of racism is just not cricket . The Sydney Morning Herald . 16 December 2005 . 19 August 2007 .

- Web site: The whole world's watching . eprints.lse.ac.uk. 31 May 2023.

- Web site: Looking Back – Episode 11 – Parliament On Demand . 25 May 2023 . ondemand.parliament.nz.

- Web site: Gleneagles Agreement . 25 May 2023 . nzhistory.govt.nz . en.

- Web site: Politics and sport – 1981 Springbok tour . New Zealand history online . Nzhistory.net.nz . 24 February 2009 . 1 October 2009.

- Web site: Battle lines are drawn – 1981 Springbok tour | NZHistory.net.nz, New Zealand history online . Nzhistory.net.nz . 24 February 2009 . 1 October 2009.

- Web site: Impact – 1981 Springbok tour | . Nzhistory.net.nz . 1 October 2009.

- Web site: Who Takes the Blame — A Society Divided Over the Springbok Tour | NZETC . nzetc.victoria.ac.nz.

- Newnham, By Batons and Barbed Wire, p. 39

- Web site: Narrating the Springbok Tour . otago.ac.nz. 31 May 2023.

- Web site: Film: Gisborne game, 1981 Springbok tour NZHistory, New Zealand history online . 23 May 2023 . nzhistory.govt.nz.

- Web site: Tour diary – 1981 Springbok tour . New Zealand history online . Nzhistory.net.nz . 1 October 2009.

- http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/media/video/game-cancelled-in-hamilton Film: game cancelled in Hamilton, 1981 Springbok tour

- Web site: Film: game cancelled in Hamilton, 1981 Springbok tour | NZHistory.net.nz, New Zealand history online . Nzhistory.net.nz . 1 October 2009.

- Web site: Film: game cancelled in Hamilton, 1981 Springbok tour NZHistory, New Zealand history online . 23 May 2023 . nzhistory.govt.nz.

- Rankin . Elizabeth . January 2007 . Banners, batons and barbed wire: Anti-apartheid images of the Springbok rugby tour protests in New Zealand . De Arte . 42 . 76 . 21–32 . 10.1080/00043389.2007.11877076 . 127562230 . 0004-3389.

- Meurant . Jacques . February 1987 . Ces lieux où Henry Dunant… Story in stone… . International Review of the Red Cross . 27 . 256 . 123–124 . 10.1017/s0020860400061155 . 0020-8604.

- Web site: Film: clash on Molesworth St – 1981 Springbok tour | NZHistory.net.nz, New Zealand history online . Nzhistory.net.nz . 1 October 2009.

- Web site: 24 May 2008 . Eddie Gay . Minto's battered helmet to go on display at Te Papa . The New Zealand Herald . 1 October 2009.

- "Lecturer admits 1981 tour sabotage", The Press, 14 July 2001.

- Web site: Eden Park revamp uncovers secret escape route . The New Zealand Herald. 7 August 2008. 25 November 2014. Edward. Gay.

- Web site: The first test: Lancaster Park, Christchurch, 15 August 1981 . 9 February 2015. New Zealand History. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 3 August 2016.

- Web site: Film: the third test – 1981 Springbok tour | NZHistory.net.nz, New Zealand history online . The New Zealand Herald . 1 October 2009.

- Book: Kayleen M . Hazlehurst . Cameron . Hazlehurst . Gangs and youth subcultures . Transaction . 2008. 9781412824323 .

- Web site: The code of silence over a tour's infamous bashing . The New Zealand Herald . 11 August 2001 . 1 October 2009 . Eugene . Bingham.

- News: Recalling the day rugby coverage was cut . Otago Daily Times. 28 May 2018. Paul. Gorman.

- Web site: John Minto – 1981 Springbok tour NZHistory, New Zealand history online . 23 May 2023 . nzhistory.govt.nz.

- "Man rugby fans hated", Sunday Star Times, 13 March 1994.

- Melissa A. Morrison . The Grassroots of the 1981 Springbok Tour: An examination of the actions and perspectives of everyday New Zealanders during the 1981 Springbok Rugby Tour of New Zealand . University of Canterbury. MA. 10.26021/4219. 2017. 10092/14533.

- Web site: Tour diary . nzhistory.govt.nz.

- http://journaltimes.com/news/local/from-the-archives-secret-site-curbs-rugby-protest/article_28d585fe-174a-11e3-b341-0019bb2963f4.html 1981: Secret site curbs rugby protest

- https://www.nytimes.com/1981/09/23/nyregion/protesters-in-albany-shout-as-springboks-triumph-in-rainfall.html Protesters in Albany shout as Springboks triumph in rainfall

- http://www.houstonpress.com/news/a-test-of-the-times-6559902 A Test of the Times

- Web site: Geoff . Adlam . Rt Hon Sir Maurice Eugene Casey, 1923 – 2012 . . 31 December 2014 . https://web.archive.org/web/20150122175600/http://my.lawsociety.org.nz/in-practice/people/obituaries/obituaries-list/rt-hon-sir-maurice-eugene-casey-1923-2012 . 22 January 2015 . dead .

- News: 21 January 2012 . Yvonne . Tahana . Judge's ruling halted divisive All Black tour . . 31 December 2014.

- News: '87 Cup healed '81 tour's wounds . Otago Daily Times . 18 November 2005 . McMurran . Alister.

- Web site: NZ Feature Project: Patu! . New Zealand Film Archive . 4 August 2006 . 1 October 2009 . dead . https://web.archive.org/web/20100522022620/http://www.filmarchive.org.nz/feature-project/pages/Patu.php . 22 May 2010.

- Web site: The Film Archive – Ready to Roll? | Blam Blam Blam – There is no Depression . https://web.archive.org/web/20110921084612/http://www.filmarchive.org.nz/readytoroll/view.php?id=28. dead. 21 September 2011.

- Web site: 1981: Hitting the Road . New Zealand Film Archive . 1 October 2009 . dead . https://web.archive.org/web/20090809224720/http://www.filmarchive.org.nz/archive_presents/1981/1981.html . 9 August 2009 .

- Web site: Helmet . Collections Online . Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa . 20 November 2010.

- Web site: Ticket to Springboks versus Waikato rugby game at Rugby Park in Hamilton on 25 July 1981 . Collections Online . Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa . 20 November 2010.

- Web site: 1981 Springbok tour . Slice of Heaven – Diversity & civil rights . Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa . 20 November 2010.

- Web site: NZ On Air | News | Press Releases . https://web.archive.org/web/20140219171519/http://www.nzonair.govt.nz/news/newspressreleases/pressrelease_2010_12_21.aspx. dead. 19 February 2014.

- Web site: Springbok tour upheaval re-enacted with Rage . Rothwell . Kimberley . 19 May 2011 . Stuff: Entertainment . 14 September 2011.

- Web site: Sunday Theatre | Television New Zealand | Entertainment | TV One, TV2 . https://web.archive.org/web/20141125041855/https://www.tvnz.co.nz/sunday-theatre/rage-4342619 . 25 November 2014 .

This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License . It uses material from the Wikipedia article " 1981 South Africa rugby union tour of New Zealand and the United States ".

Except where otherwise indicated, Everything.Explained.Today is © Copyright 2009-2024, A B Cryer, All Rights Reserved. Cookie policy .

Springbok Tour 1981

A DigitalNZ Story by National Library of New Zealand Topics

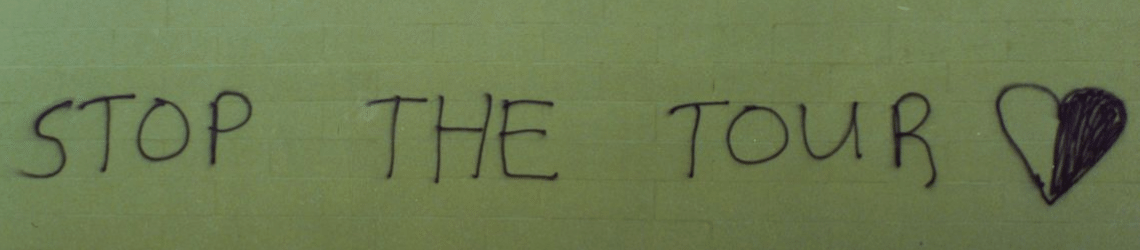

Protests against the South African rugby team touring New Zealand divided the country in 1981. Discover the reasons behind this civil disobedience, as well as the demonstrations, police actions and the politics of playing sports. SCIS no. 1809122

social_sciences , english , history

Protesters in Hamilton during a demonstration against the 1981 Springbok tour - Photograph taken by Phil Reid

Alexander Turnbull Library

Anti-tour protestors and police in Molesworth Street, Wellington - Photograph taken by Ian Mackley

Okay, step forward any lyin' commy…,

Try revolution

This Leanne Pooley-directed film aims to show how the events of the 1981 Springbok tour in Aotearoa played out in South Africa.

NZ On Screen

The 1981 Springbok rugby tour

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Sports and politics

Red Squad and anti- tour demonstrators

Springbok Tour protest programme

Protest badges - 1981

School children protesting

Young anti-springbok tour protester

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

Tour diary - 1981 Springbok tour

Blazey discussing the 1981 springbok tour.

Anti-Springbok tour protest reflects on thirty years since first game

Radio New Zealand

John Miller has documented M¬āori protest since the 1970's, including the Springbok Tour.

T-shirt, 'No Tour'

This T-shirt was made for protestors to wear during the Springbok rugby tour of 1981.

1956 rugby ball and John Minto helmet

Features the protester John Minto's helmet from Springbok rugby tour protests.

Barbed wire barrier protecting a rugby ground from anti-Springbok tour protestors.

TV movie Rage recreates the 1981 Springbok tour, which saw violent clashes between protestors and police.

Patu!, 1983

New Zealand 1981 South Africa 2013

Woman protestor angered by police batoning demonstrators during a Springbok rugby tour protest

These records are part of a July 1981 petition to Robert Muldoon, then-Prime Minister of New Zealand, calling for the Springbok rugby team to be refused entry into the country.

Petition Cards to Robert Muldoon

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

The Year 1981

Release Mandela!

These mugs were sold to raise money for protest funds for the 1981 anti-Springbok Tour movement.

The continuing saga of "The Tour"

Apartheid. Stop the tour

This badge was worn by protesters against contacts between South African and New Zealand sporting teams in the 1970s.

Halt All Racist Tours badge

Services to Schools

Women against the 1981 tour

Don't mention the tour

The 1981 springbok tour, the 1981 springbok tour of new zealand, 1981 springbok tour: poster collection, riot 111: 1981, the great divide, the rugby tour that split us into two nations.

PR 24 baton

Rugby and apartheid

1981 Anti-Springbok tour demonstration

The springbok tour of 1981 – 25 years on.

“He aint dead Sir”

Anti-tour clash

1981 Springbok tour

National Library of New Zealand

NZSIS reports on 1981 Springbok rugby tour protests

Red squad revisited, 1981 springbok tour perspectives, the 1981 springbok tour and explosive revelations, tainted games.

1981 Springbok tour images

Research paper

National ideals or national interest: New Zealand and South Africa, 1981 - 1994

Clash on molesworth st, mirror image, artists against the springbok tour, anti-springbok-tour veterans on the power of hart, remembering the 1981 springbok tour, more than just rugby, a tour like no other: school journal year 7: part 04 no. 02: 2011 or, opinion around new zealand on the 1981 springbok tour, rugby, racism and fear, the grassroots of the 1981 springbok tour.

Merata Mita’s Patu! — a landmark in Aotearoa's film history, is based on the civil disobedience movement during the winter of 1981 Springbok tour.

New Zealand Protests

The Dawn Raids

Māori Protests

Covering the springbok tour, 1981 springbok rugby tour — cardboard and clown suits.

NZ Sporting History: The 1981 Springbok Tour

35 years ago: springbok tour protests in wellington, covering the tour, protest - tohe.

1981 South Africa rugby union tour of New Zealand and the United States

The 1981 South African rugby tour (known in New Zealand as the Springbok Tour , and in South Africa as the Rebel Tour ) polarised opinions and inspired widespread protests across New Zealand. The controversy also extended to the United States, where the South African rugby team continued their tour after departing New Zealand. [1] [2]

Tour of New Zealand

Hamilton: game cancelled, wellington: molesworth street protest, christchurch, auckland: plane invasion, the protest movement, tour of the united states, albany: pipe bomb, the matches, in new zealand, in united states, touring party, in new zealand culture, notes and references, bibliography, external links.

Apartheid had made South Africa an international pariah , and other countries were strongly discouraged from having sporting contacts with it. Rugby union was (and is) an extremely popular sport in New Zealand, and the South African team known as the Springboks were considered to be New Zealand's most formidable opponents. [3] Therefore, there was a major split in opinion in New Zealand as to whether politics should influence sport in this way and whether the Springboks should be allowed to tour.

Despite the controversy, the New Zealand Rugby Union decided to proceed with the tour. The government of Prime Minister Robert Muldoon was called on to ban it, but decided that commitments under the Gleneagles Agreement did not require the government to prevent the tour, and decided not to interfere due to their public position of "no politics in sport". Major protests ensued, aiming to make clear many New Zealanders' opposition to apartheid and, if possible, to stop the matches taking place. This was successful at two games, but also had the effect of creating a law and order issue: whether a group of protesters could be allowed to prevent a lawful game taking place.

The dispute was similar to that involving Peter Hain in the United Kingdom in the early 1970s, when Hain's Stop the Tour campaign clashed with the more conservative 'Freedom Under Law' movement championed by barrister Francis Bennion . The allegedly excessive police response to the protests also became a focus of controversy. Although the protests were among the most intense in New Zealand's recent history, no deaths or serious injuries resulted.

After the tour, no official sporting contact took place between New Zealand and South Africa until the early 1990s, after apartheid had been abolished. The tour has been said to have led to a decline in the popularity of Rugby Union in New Zealand, until the 1987 Rugby World Cup .

The Springboks and New Zealand's national rugby team, the All Blacks , have a long tradition of intense and friendly sporting rivalry. [4]

From 1948 to 1969, the South African apartheid regime affected team selection for the All Blacks, with selectors passing over Māori players for some All Black tours to South Africa. [5]

Opposition to sending race -based teams to South Africa grew throughout the 1950s and 1960s, and prior to the All Blacks' tour of South Africa in 1960, 150,000 New Zealanders – 6.25% of the country's population at that time – signed a petition supporting a policy of "No Maoris, No Tour". [5] Despite this, the tour still happened, and in 1969, Halt All Racist Tours (HART) was formed. [6]

During the 1970s, public protests and political pressure forced on the New Zealand Rugby Union (NZRFU) the choice of either fielding a team not selected by race, or not touring South Africa: [5] after South African rugby authorities continued to select Springbok players by race, [4] the Norman Kirk Labour Government barred the Springboks from touring New Zealand during 1973. [6] In response, the NZRFU protested about the involvement of "politics in sport".

On 28 March 1976, the final game of ex-All Black Fergie McCormick was played at Lancaster Park in Christchurch, to which two Springbok players had been invited. Ten days before the game, protesters had written "WELCOME TO RACIST GAME" in 20-foot high letters on the pitch using weed-killer. [7] [8] [9]

The All Blacks toured South Africa with the blessing of the newly elected New Zealand Prime Minister, Robert Muldoon . [10] In response to this, twenty-five African nations boycotted the 1976 Summer Olympics in Montreal, [11] stating that in their view, the All Blacks tour gave tacit support to the apartheid regime in South Africa: the IOC declined to ban New Zealand from the Olympics on the grounds that rugby union was no longer an Olympic sport.

The 1976 tour attracted several anti-apartheid protests in New Zealand, including one on 28 May 1976 in Cathedral Square, Christchurch which attracted 1000–1500 people and included guerrilla theatre. [12] [13] Protesters also attempted to disrupt television coverage of the first test by vandalising the Makara Hill microwave station in Wellington, which was responsible for relaying programming in and out of TV One 's Avalon studios. [14]

The 1976 tour contributed to the creation of the Gleneagles Agreement , that was adopted by the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in 1977. [15]

By the early 1980s, the pressure from other countries and from protest groups in New Zealand such as HART reached a head when the NZRU proposed a Springbok tour for 1981. This became a topic of political contention due to the international sports boycott . After the Australian Prime Minister, Malcolm Fraser , refused permission for the Springboks' aircraft to refuel in Australia, [16] the Springboks' flights to and from New Zealand went via Los Angeles and Hawaii. [17]

Despite pressure for the Muldoon government to cancel the tour, permission was granted for it, and the Springboks arrived in New Zealand on 19 July 1981. Since 1977 Muldoon's government had been a party to the Gleneagles Agreement , in which the countries of the Commonwealth accepted that it was:

the urgent duty of each of their Governments vigorously to combat the evil of apartheid by withholding any form of support for, and by taking every practical step to discourage contact or competition by their nationals with sporting organisations, teams or sportsmen from South Africa or from any other country where sports are organised on the basis of race, colour or ethnic origin.

Despite this, Muldoon also argued that New Zealand was a free and democratic country, and that "politics should stay out of sport." In the years following the Gleneagles Agreement, it seemed that New Zealand government members did not feel bound to the Gleneagles agreement, and disregarded it. However, some historians claim that, "'the [Gleneagles] agreement remained vague enough to avoid the New Zealand government from having to use coercive powers such as withdrawing visas and passports."' [18] This means Muldoon's government technically wasn't bound to the agreement to the extent it outwardly appeared to the public. In addition to this, Ben Couch , who was the minister for Maori development at the time, stated, 'I believe that the Gleneagles agreement has been forced upon us by people who do not have the same kind of democracy that we have.' [19]

Muldoon made some effort to discourage the tour and stated that he could see ‘nothing but trouble coming from this.’ [20] ‘ A Springbok tour would dash to the ground all that has been achieved as a result of international acceptance ,' wrote deputy Prime Minister Brian Talboys to the chairman of the NZRFU in a further attempt to discourage the tour, ' [the tour] may affect the harmonious development of the Commonwealth and international sport .' [18]

Some rugby supporters echoed the separation of politics and sport, [21] [22] while other rugby supporters argued that if the tour were cancelled, there would be no reporting of the widespread criticism of apartheid in New Zealand in the controlled South African media.

Muldoon's critics felt that he allowed the tour in order for his National Party to secure the votes of rural and provincial conservatives in the general election later in the year, which Muldoon won. [23] Along with Muldoon's policy of ‘leaving sporting contacts to sporting bodies,’ Muldoon also held the opinion that the disruption and division of New Zealand was not caused by the NZFRU, nor the Springboks, but the anti-tour protesters themselves. [24] This argument was vehemently refuted by anti-tour voices, political activist Tom Newnham claimed that the government enabled ‘the greatest breakdown in law and order [New Zealand] has ever witnessed.’ [25]

The ensuing public protests polarised New Zealand: [23] while rugby fans filled the football grounds, protest crowds filled the surrounding streets, and on one occasion succeeded in invading the pitch and stopping the game. [26]

To begin with, the anti-tour movement was committed to non-violent civil disobedience , demonstrations and direct action . [ citation needed ] As protection for the Springboks, the police created two special riot squads, the Red and Blue Squads. [27] [28] These police were, controversially, the first in New Zealand to be issued with visored riot helmets and long batons (more commonly the side-handle baton ). [ citation needed ] Some protesters were intimidated and interpreted this initial police response as overkill and heavy-handed tactics. [ citation needed ] After early disruptions, police began to require that all spectators assemble in sports grounds at least an hour before kick-off. [ citation needed ] While the protests were meant to be largely peaceful resistance to the Springbok tour, quite often, there were 'violent confrontations with rugby supporters and specially trained riot police.' [29]

At Gisborne on the day before the match anti-tour activists, including Mereana Pitman, gained access to the pitch with a vehicle and tipped broken glass on the pitch. [30] On 22 July, [31] protesters managed to break through a fence, but quick action by spectators and ground security prevented the game being disrupted. Some protesters were beaten by police. From the very first match of the tour in Gisborne, protester tension levels ran high, and one protester, cartoonist Murray Ball , who was the son of an All Black, recalled that it ‘was strange for New Zealanders to feel so aggressive towards other New Zealanders’ and that he was 'scared as hell' when he came up against pro-tour defenders. [30]

- MP for Tamaki

- Electoral history

Leader of the National Party

- 1974 leadership election

- 1984 leadership election

Leader of the Opposition

- Shadow Cabinet I

- Dancing Cossacks advertisement

Prime Minister of New Zealand

- Third National Government

- Fitzgerald v Muldoon

- Bastion Point Occupation

- Carless days

- 1981 Springbok Tour

- Closer Economic Relations

- 1984 New Zealand constitutional crisis

General elections

At Rugby Park, Hamilton (the site of today's Waikato Stadium ), on 25 July, [31] about 350 protesters invaded the pitch after pulling down a fence. The police arrested about 50 of them over a period of an hour, but were concerned that they could not control the rugby crowd, who were throwing bottles and other objects at the protesters. [32] Following reports that a stolen light plane (piloted by Pat McQuarrie) [33] was approaching the stadium, police cancelled the match. [32]

The protesters were ushered from the ground and were advised by protest marshals to remove any anti-tour insignia from their attire, with enraged rugby spectators lashing out at them. Gangs of rugby supporters waited outside Hamilton police station for arrested protesters to be processed and released, and assaulted some protesters making their way into Victoria Street. [34] There are many reports from protesters feeling unsafe during this protest, ‘It was terrifying, I don’t know how big the crowd was, but they were clearly furious…The police looked vulnerable as they spread out around the whole ground,’ [35] recollects one protester who was at the Hamilton Game where a conflict between those for and against the tour broke out.

The aftermath of the Hamilton game, followed by the bloody batoning of marchers in Wellington 's Molesworth Street in the following week, in which police batoned bare-headed protesters, led to the radicalisation of the protest movement. There are many instances where the protesters had to fear for their safety, especially considering the violence that began on Molesworth Street, where police are said to have “behaved rather too similarly to South African police, '' according to Tom Newnham . [36] Former police officer, Ross Muerant , who was pro-tour, speaks of the Molesworth St protest: "The protestors, who so obviously lacked self-control, were that evening privy to a classic display of discipline." [37] This perspective of the police tactics has severe opposition from anti-tour activists, with claims that protesters were 'savagely attacked by police,' and that ‘police provoked violence.' [29] While Newnham's claims that the violence towards protesters from police was unjustified was likely true in his experience, Muerant maintains that there were protesters who intended to inflict "serious injury or disfigurement" on the police. [37]

Because of this, many protesters began to wear motorcycle or bicycle helmets to protect themselves from batons and head injury . [38] [39]

The authorities strengthened security at public facilities after protesters disrupted telecommunications by damaging a waveguide on a microwave repeater , disrupting telephone and data services, though TV transmissions continued as they were carried by a separate waveguide on the tower. [40] Army engineers were deployed, [ citation needed ] and the remaining grounds were surrounded with razor wire and shipping container barricades to decrease the chances of another pitch invasion. At Eden Park, an emergency escape route was constructed from the visitors' changing rooms for use if the stadium was overrun by protesters. Crowds of anti-tour protesters stood outside as the police were overwhelmed but the hundreds of police still managed to prevent the protesters from entering the stadium. [41]

At Lancaster Park , Christchurch, on 15 August, [31] some protesters managed to break through a security cordon and a number invaded the pitch. [ citation needed ] They were quickly removed and forcibly ejected from the stadium by security staff and spectators. [ citation needed ] A large demonstration managed to occupy the street adjacent to the ground and confront the riot police. [42] Spectators were kept in the ground until the protesters dispersed. [ citation needed ]

A low-flying Cessna 172 piloted by Marx Jones and Grant Cole disrupted the final test at Eden Park , Auckland , on 12 September [31] by dropping flour-bombs on the pitch. In spite of the bombing, the game continued. [43] "Patches" of criminal gangs, such as traditional rivals Black Power and the Mongrel Mob , were also evident [ citation needed ] (The Black Power were Muldoon supporters [44] ). Footage [ according to whom? ] was shown of the Clowns Incident , where police were shown beating unarmed clowns with batons. [45] The same day in Warkworth, Dunedin and Timaru protesters stormed the local TV transmitters and shut off coverage of the Auckland game. [46] [47]

Some of the protest had the dual purpose of linking racial discrimination against Māori in New Zealand to apartheid in South Africa. Some of the protesters, particularly young Māori, felt frustrated by the image of New Zealand as a paradise for racial unity. [22] Many opponents of racism in New Zealand in the early 1980s saw it as useful to use the protests against South Africa as a vehicle for wider social action. [ citation needed ] However, some Maori supported the tour and attended games. [ citation needed ] John Minto , the national organizer for HART , thought that the tour "stimulate[d] the whole debate about racism, and the place of Maori in our community." [48] Political activist Tom Newnham’s opinion echoes that of Minto’s, albeit considerably more radical, stating that "we are basically the same as white South Africans, just as racist." [49] Some of those protesting racism in South Africa felt inclined to reflect on the racial divide in their own country, before condemning another – part-maori rugby spectator Kevin Taylor did not join the protests because he ‘wanted New Zealand to fix its own issues before New Zealanders started telling other countries how to fix their problems.’ [50]

With the American leg of the tour following directly after the events of New Zealand, further protests and clashes with police were expected. [2] Threats of riots caused city officials in Los Angeles, Chicago, New York City and Rochester to withdraw their previous authorisation for the Springboks to play in their cities. [2]

The Springboks' match against the Midwest All Stars team had originally been intended to be played in Chicago. Following the anti-apartheid protests, it was secretly rescheduled to the mid morning of Saturday 19 September at Roosevelt Park in Racine, Wisconsin . [51] The clandestine strategy seemingly worked as around 500 spectators gathered to watch the match. Late in the game, however, a small number of protesters arrived to disrupt proceedings and two were arrested after a brief altercation broke out on the field. [51]

The cancelled New York City match against the Eastern All Stars was moved upstate to Albany . [52] The long serving Mayor of Albany, Erastus Corning, maintained that there was a right of peaceful assembly to "publicly espouse an unpopular cause," despite his own stated view that "I abhor everything about apartheid". [51]

Governor Hugh Carey argued that the event should be barred as the anti-apartheid demonstrators presented an "imminent danger of riot", but a Federal court ruling allowing the game to be played was upheld in the United States Court of Appeals . A further appeal to Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall was also overruled on the grounds of free speech . [52]

The match went ahead with around a thousand demonstrators (including Pete Seeger ) corralled 100 yards away from the field of play, which was surrounded by the police. No violence occurred at the game but a pipe bomb was set off in the early morning outside the headquarters of the Eastern Rugby Union resulting in damage to the building estimated at $50,000. [52] No one was injured.

The final match of the tour, against the United States national team , took place in secret at Glenville in upstate New York. [53] The thirty spectators recorded at the match is the lowest ever attendance for an international rugby match. [1]

- Manager: Johan Claassen

- Assistant Manager: Abe Williams

- Coach: Nelie Smith ( Free State )

- Captain: Wynand Claassen

The Muldoon government was re-elected in the 1981 election losing three seats to leave it with a majority of one.

The NZRU constitution contained much high-minded wording about promoting the image of rugby and New Zealand, and generally being a benefit to society. In 1985, the NZRU proposed an All Black tour of South Africa: two lawyers successfully sued it, claiming such a tour would breach its constitution. A High Court injunction by Justice Casey saw the tour cancelled. [55] [56]

Afterwards, the All Blacks would not tour South Africa until after the fall of the apartheid regime, with the next official tour in 1992. After the 1985 tour was cancelled, an unofficial tour took place a year later by a team that included 28 out of the 30 All Blacks selected for the 1985 tour, known as the New Zealand Cavaliers , a team that was often advertised in South Africa as the All Blacks and/or depicted with the Silver Fern.

The role of the police also became more controversial as a result of the tour. [ citation needed ]

After the All Blacks won the 1987 Rugby World Cup , rugby union was once again the dominant sport – in both spectator and participant numbers – in New Zealand. [57]

- Prominent artist Ralph Hotere painted a Black Union Jack series of paintings in protest against the tour.

- Merata Mita 's documentary film Patu! tells the tale of the tour from a left-wing perspective. [58]

- Music popularly associated with the tour included the punk band RIOT 111 , and the songs "Riot Squad" by the Newmatics and "There Is No Depression in New Zealand" by Blam Blam Blam . [59]

- The TVNZ 1980s police drama Mortimer's Patch included a flashback episode of the (younger) main character's tour police duties

- In 1984 Geoff Chapple wrote the book 1981: The Tour , chronicling the events from the protesters' perspective. ISBN 978-0-589-01534-3

- In 1999 Glenn Wood's biography Cop Out covered the tour from the perspective of a frontline policeman. ISBN 978-0-908704-89-7

- David Hill's book The Name of the Game is the story of a schoolboy's personal struggles during the tour. ISBN 978-0-908783-63-2

- Tom Newnham 's book By Batons And Barbed Wire is one of the largest collections of photos and general information of the protest movement during the tour. ISBN 978-0-473-00253-4 (hardback). ISBN 978-0-473-00112-4 (paperback)

- The documentary 1981: A Country at War chronicled the tour from various perspectives. [60]

- Te Papa has objects related to the tour including images, helmets [61] [62] and an entrance ticket. [63] The exhibition Slice of Heaven: 20th Century Aotearoa has a section about the tour. [64]

- Rage , a dramatisation of the tour by Tom Scott , was filmed in mid-2011 [65] [66] and was broadcast on TV One on 4 September 2011. [67]

- The Engine Room , a play by Ralph McCubbin Howell , opened at BATS Theatre in Wellington on 27 September 2011. It contrasts the stories and viewpoints of John Key and Helen Clark during the tour and the 2008 general election .

- The second series of the television show Westside takes place during the events of the tour and portrays the main characters' involvement in several of the major incidents.

- 1971 South Africa rugby union tour of Australia

- History of South Africa in the apartheid era

- Robert Muldoon

- New Zealand Cavaliers

- Politics and sports

- Sporting boycott of South Africa

- 1 2 Miller, Chuck (10 April 1995). "Rugby in the national spotlight: The 1981 USA tour of the Springboks" . Rugby Magazine . Archived from the original on 22 October 2007 . Retrieved 14 May 2014 .

- 1 2 3 Grondahl, Paul (6 December 2013). "All eyes were on Albany and Apartheid in 1981" . Times Union . Archived from the original on 13 May 2015 . Retrieved 13 May 2015 .

- ↑ "All Blacks versus Springboks" . nzhistory.net.nz. 12 June 2014 . Retrieved 13 May 2015 .

- 1 2 Watters, Steve. "A long tradition of rugby rivalry" . nzhistory.net.nz . Retrieved 17 January 2007 .

- 1 2 3 Watters, Steve. " 'Politics and sport don't mix' " . nzhistory.net.nz . Retrieved 17 January 2007 .

- 1 2 Watters, Steve. "Stopping the 1973 tour" . nzhistory.net.nz . Retrieved 17 January 2007 .

- ↑ "Say it in acid" . paperspast.natlib.govt.nz . Retrieved 2 March 2023 .

- ↑ "Message with a difference" . The Press . 29 March 1976.

- ↑ "WELCOME TO RACIST GAME" . paperspast.natlib.govt.nz . Retrieved 2 March 2023 .

- ↑ Fortuin, Gregory (20 July 2006). "It's time to close the final chapter". The New Zealand Herald .

- ↑ "On This Day 17 July 1976" . BBC. 17 July 1976 . Retrieved 17 January 2007 .

- ↑ "Rally in Cathedral square" . paperspast.natlib.govt.nz . Retrieved 2 March 2023 .

- ↑ "1500 in City Protest". Christchurch Star . 29 May 1976. p. 15.

- ↑ "Saboteurs try to cut rugby TV coverage" . The Press . 26 July 1976. p. 1.

- ↑ Watters, Steve. "From Montreal to Gleneagles" . nzhistory.net.nz . Retrieved 17 January 2007 .

- ↑ "When talk of racism is just not cricket" . The Sydney Morning Herald . 16 December 2005 . Retrieved 19 August 2007 .

- ↑ Chapple 1984 , p. 60.

- 1 2 "The whole world's watching" (PDF) . eprints.lse.ac.uk . Retrieved 31 May 2023 .

- ↑ "Looking Back – Episode 11 – Parliament On Demand" . ondemand.parliament.nz . Retrieved 25 May 2023 .

- ↑ "Gleneagles Agreement" . nzhistory.govt.nz . Retrieved 25 May 2023 .

- ↑ "Politics and sport – 1981 Springbok tour" . New Zealand history online . Nzhistory.net.nz. 24 February 2009 . Retrieved 1 October 2009 .

- 1 2 "Battle lines are drawn – 1981 Springbok tour | NZHistory.net.nz, New Zealand history online" . Nzhistory.net.nz. 24 February 2009 . Retrieved 1 October 2009 .

- 1 2 "Impact – 1981 Springbok tour | " . Nzhistory.net.nz . Retrieved 1 October 2009 .

- ↑ "Who Takes the Blame — A Society Divided Over the Springbok Tour | NZETC" . nzetc.victoria.ac.nz .

- ↑ Newnham, By Batons and Barbed Wire, p. 39

- ↑ Ardern, Crystal (22 July 2006). "Springbok Tour 1981" . Waikato Times . Archived from the original on 15 October 2008.

- ↑ "Protest! The Voice of Dissent at the Nelson Provincial Museum" (PDF) . Evidence . New Zealand Police Museum. April 2007. p. 2.

- ↑ "Springbok Tour Special | CLOSE UP News" . TVNZ. 4 July 2006 . Retrieved 1 October 2009 .

- 1 2 "Narrating the Springbok Tour" (PDF) . otago.ac.nz . Retrieved 31 May 2023 .

- 1 2 "Film: Gisborne game, 1981 Springbok tour | NZHistory, New Zealand history online" . nzhistory.govt.nz . Retrieved 23 May 2023 .

- 1 2 3 4 "Tour diary – 1981 Springbok tour" . New Zealand history online . Nzhistory.net.nz . Retrieved 1 October 2009 .

- 1 2 Film: game cancelled in Hamilton, 1981 Springbok tour , Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Updated 11 May 2007. Retrieved 24 December 2008.

- ↑ Chapple 1984 , pp. 77–78, 91, 99–102.

- ↑ "Film: game cancelled in Hamilton, 1981 Springbok tour | NZHistory.net.nz, New Zealand history online" . Nzhistory.net.nz . Retrieved 1 October 2009 .

- ↑ "Film: game cancelled in Hamilton, 1981 Springbok tour | NZHistory, New Zealand history online" . nzhistory.govt.nz . Retrieved 23 May 2023 .

- ↑ Rankin, Elizabeth (January 2007). "Banners, batons and barbed wire: Anti-apartheid images of the Springbok rugby tour protests in New Zealand" . De Arte . 42 (76): 21–32. doi : 10.1080/00043389.2007.11877076 . ISSN 0004-3389 . S2CID 127562230 .

- 1 2 Meurant, Jacques (February 1987). "Ces lieux où Henry Dunant… Story in stone… " . International Review of the Red Cross . 27 (256): 123–124. doi : 10.1017/s0020860400061155 . ISSN 0020-8604 .

- ↑ "Film: clash on Molesworth St – 1981 Springbok tour | NZHistory.net.nz, New Zealand history online" . Nzhistory.net.nz . Retrieved 1 October 2009 .

- ↑ Eddie Gay (24 May 2008). "Minto's battered helmet to go on display at Te Papa" . The New Zealand Herald . Retrieved 1 October 2009 .

- ↑ "Lecturer admits 1981 tour sabotage", The Press, 14 July 2001.

- ↑ Gay, Edward (7 August 2008). "Eden Park revamp uncovers secret escape route" . The New Zealand Herald . Retrieved 25 November 2014 .

- ↑ "The first test: Lancaster Park, Christchurch, 15 August 1981" . New Zealand History . Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 9 February 2015 . Retrieved 3 August 2016 .

- ↑ "Film: the third test – 1981 Springbok tour | NZHistory.net.nz, New Zealand history online" . The New Zealand Herald . Retrieved 1 October 2009 .

- ↑ Hazlehurst, Kayleen M; Hazlehurst, Cameron, eds. (2008). Gangs and youth subcultures . Transaction. ISBN 9781412824323 . [ dead link ]

- ↑ Bingham, Eugene (11 August 2001). "The code of silence over a tour's infamous bashing" . The New Zealand Herald . Retrieved 1 October 2009 .

- ↑ Gorman, Paul (28 May 2018). "Recalling the day rugby coverage was cut" . Otago Daily Times .

- ↑ Chapple 1984 , pp. 288–291.

- ↑ "John Minto – 1981 Springbok tour | NZHistory, New Zealand history online" . nzhistory.govt.nz . Retrieved 23 May 2023 .

- ↑ "Man rugby fans hated", Sunday Star Times, 13 March 1994.

- ↑ Melissa A. Morrison (2017). The Grassroots of the 1981 Springbok Tour: An examination of the actions and perspectives of everyday New Zealanders during the 1981 Springbok Rugby Tour of New Zealand (MA thesis). University of Canterbury. doi : 10.26021/4219 . hdl : 10092/14533 .

- 1 2 3 4 1981: Secret site curbs rugby protest . The Journal Times. 8 September 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Protesters in Albany shout as Springboks triumph in rainfall . The New York Times . 23 September 1981.

- 1 2 A Test of the Times . Houston Press. 13 December 2001.

- ↑ "Tour diary" . nzhistory.govt.nz .

- ↑ Adlam, Geoff. "Rt Hon Sir Maurice Eugene Casey, 1923 – 2012" . New Zealand Law Society . Archived from the original on 22 January 2015 . Retrieved 31 December 2014 .

- ↑ Tahana, Yvonne (21 January 2012). "Judge's ruling halted divisive All Black tour" . The New Zealand Herald . Retrieved 31 December 2014 .

- ↑ McMurran, Alister (18 November 2005). " '87 Cup healed '81 tour's wounds". Otago Daily Times .

- ↑ "NZ Feature Project: Patu!" . New Zealand Film Archive. 4 August 2006. Archived from the original on 22 May 2010 . Retrieved 1 October 2009 .

- ↑ "The Film Archive – Ready to Roll? | Blam Blam Blam – There is no Depression" . Archived from the original on 21 September 2011.

- ↑ "1981: Hitting the Road" . New Zealand Film Archive. Archived from the original on 9 August 2009 . Retrieved 1 October 2009 .

- ↑ "Helmet" . Collections Online . Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa . Retrieved 20 November 2010 .

- ↑ "Ticket to Springboks versus Waikato rugby game at Rugby Park in Hamilton on 25 July 1981" . Collections Online . Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa . Retrieved 20 November 2010 .

- ↑ "1981 Springbok tour" . Slice of Heaven – Diversity & civil rights . Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa . Retrieved 20 November 2010 .

- ↑ "NZ On Air | News | Press Releases" . Archived from the original on 19 February 2014.

- ↑ Rothwell, Kimberley (19 May 2011). "Springbok tour upheaval re-enacted with Rage" . Stuff: Entertainment . Retrieved 14 September 2011 .

- ↑ "Sunday Theatre | Television New Zealand | Entertainment | TV One, TV2" . Archived from the original on 25 November 2014.

- Cameron, Don (1981). Barbed Wire Boks . Auckland, New Zealand: Rugby Press Ltd. ISBN 978-0-908630-05-9 .

- Chapple, Geoff (1984). 1981: The Tour . Wellington: A H & A W Reed. ISBN 978-0-589-01534-3 .

- Newnham, Tom (1981). By Batons and Barbed Wire . New Zealand: Real Pictures Ltd. ISBN 978-0-473-00112-4 .

- Richards, Trevor (1999). Dancing on Our Bones: New Zealand, South Africa, Rugby and Racism . Wellington, New Zealand: Bridget Williams Books. ISBN 1-877-242-004 .

- Posters at Christchurch City Libraries

- Images of the events surrounding the Springbok Tour in the collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

- Online account

- A time line and references

- The 1981 Springbok Tour

- The 1981 Springbok Tour, including history, images and video (NZHistory)

- Letters solicited from the New Zealand public after the 1981 Springbok Tour [ permanent dead link ]

Related Research Articles

The South Africa national rugby union team commonly known as the Springboks , is the country's national team governed by the South African Rugby Union. The Springboks play in green and gold jerseys with white shorts. Their emblem is a native antelope, the Springbok, which is the national animal of South Africa. The team has been representing South African Rugby Union in international rugby union since 30 July 1891, when they played their first test match against a British Isles touring team. Currently, the Springboks are the number one ranked rugby team in the world and are the reigning World Champions, having won the World Cup on a record four occasions. They are also the second nation to win the World Cup consecutively.

The Polynesian Panther Party (PPP) was a revolutionary social justice movement formed to target racial inequalities carried out against indigenous Māori and Pacific Islanders in Auckland, New Zealand. Founded by a group of young Polynesians on 16 June 1971, the Panthers worked to aid in community betterment through activism and protest. Besides peaceful protests, they helped provide education, legal aid, and other social resources, such as ESOL classes and youth community programs. The group was explicitly influenced by the American Black Panther Party, particularly Huey Newton’s policy of black unity through his global call-to-action, as well as his ideology of intercommunalism. The movement galvanised widespread support during the Dawn Raids of the 1970s, and greatly helped contribute to the modern pan-Polynesian ethnic identity in New Zealand called Pasifika.