Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model: A simple explanation

Disclaimer: Some posts on Tourism Teacher may contain affiliate links. If you appreciate this content, you can show your support by making a purchase through these links or by buying me a coffee . Thank you for your support!

Prof. Richard Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model is a core theoretical underpinning for many tourism research and analyses. It is also a core component of many travel and tourism management curriculums. But what does it mean?

In this article I will give you a simple explanation of Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model. I promise, by the end of this short post you will understand exactly how this model works and why it is so important in travel and tourism management….

So what are you waiting for? Read on to find out more..

What is Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model?

How did the tourism area life cycle model come about, #1 exploration, #2 involvement, #3 development, #4 consolidation, #5 stagnation, #6 decline or rejuvenation, the positive aspects of butler’s tourism area life cycle model, the negative aspects of butler’s tourism area life cycle model, to conclude.

Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model provides a fundamental underpinning to travel and tourism management of destinations. Not sure what that means? Well, basically, it is the theory underneath the story.

It sounds complicated on the outside, doesn’t it? But actually, it really isn’t complicated at all!

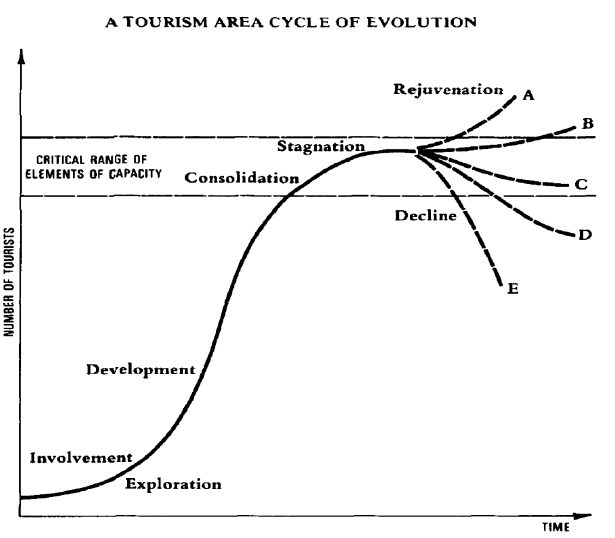

Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model is a simplistic linear model. Using a graph, it plots the different stages in tourism development in accordance with the x and y axis of tourist number growth and time. Within this, Butler’s model demonstrates 6 stages of tourism development.

OK, enough with the complicated terminology- lets break this down further. What is Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model in SIMPLE language?

To put it simply; Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model is a line graph that shows the different stages in tourism development over time.

Whilst sustainable tourism has been a buzz word for a while now, it wasn’t always the focus of tourism planning and development .

Back in the 1970s and 1980s many tourism entrepreneurs and developers were not thinking about the longevity of their businesses (this still happens a lot, particularly in developing countries, where education and training may be limited). These business men and women simply saw Dollar signs and jumped right in.

The result? Ill-thought out plans and unsustainable tourism endeavours.

Examples of unsustainable tourism with ill-thought out long term plans include: Overtourism in Maya Bay, Thailand , littering on Mount Everest and the building of unsightly high-rise hotels in Benidorm.

Professor Richard Butler wanted to give stakeholders in tourism some guidance. Something generic enough that it could be applied to a range of tourism development scenarios; whether this be a destination , resort, or tourist attraction .

This saw the birth of Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model.

Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model: How does it work?

OK, lets get down to it- how does this theory actually work?

Well, actually it’s pretty simple.

Butler created a visual, graphical depiction of tourism development. People like visuals- it helps us to understand. You can see this below.

As you can see in the image above, Butler identified six stages of tourist area evolution.

The axis do not have any specific numbers, which means that this model can easily be applied to a number of different situations and contexts.

The intention is for those who are involved with tourism planning and development to use this model as a guide. This can encourage critical thinking and the development of alternative and contingency plans. It helps to develop sustainable tourism practices.

The six stages of tourist area evolution

Butler outlined six specific stages of tourism development. Well, actually it’s five specific stages and the last ‘stage offers a variety of outcomes (I’ll explain this shortly).

Butler wanted to demonstrate that tourism development, like many things in life, is not a static process. It experiences change. Changes happens for many reasons- growth in tourism numbers, changes in taste, marketing and the media, external influences such as natural disasters or terrorism.

Butler’s model demonstrates that tourism destinations or attractions will typically follow the path outlined, experiencing each of the six stages. This will happen at different paces and at different times for different types of tourism development.

Below, I will explain which each stage of tourist evolution is referring to.

The exploration stage marks the beginning.

Tourism is limited. The social and economic benefits are small.

Tourist attractions are likely to be focused on nature or culture .

This is the primary phase when Governments and local people are beginning to think about tourism and how they could capitalise and maximise their opportunities in this industry.

This is the start of tourism planning .

The involvement stage marks the beginning of tourism development.

Guest houses may start to open. Foreign investors may start to show an interest in development. Governments may be under pressure to develop transport infrastructure and community resources, such as airports, road layouts and healthcare provision.

The involvement stage may mark the emergence of seasonality in tourism.

During the development stage there will be lots of building and planning.

New roads, train stations and airports may be built. New tourist attractions may emerge. Hotels and hospitality provisions will be put in place.

During the development phase there will likely be an increase in marketing and promotion of the destination. There could be increased media and social media coverage.

During this time the tourist population may begin to out-number the local population. Local control becomes less common and top-down processes and international organisations begin to play a key role in the management of tourism.

During the consolidation stage tourism growth slows. This may be intentional, to limit tourist numbers or to keep tourism products and services exclusive, or it may be unintentional.

There will generally be a close tie between the destination’s economy and the tourism industry. In some cases, destinations have come to rely on tourism as a dominant or their main source of income.

Many international chains and conglomerates will likely be represented in the tourism area. This represents globalisation and can have a negative impact on the economy of the destination as a result of economic leakage .

It is during this stage that discontent from the local people may become evident. This is one of the negative social impacts of tourism .

The stagnation stage represents the beginning of a decline in tourism.

During this time visitor numbers may have reached their peak and varying capacities may be met.

The destination may simply be no longer desirable or fashionable.

It is during this time that we start to see the negative impacts of overtourism . There will likely be economic, environmental and social consequences.

The final stage of Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model represents a range of possible outcomes for the destinations along the spectrum between rejuvenation and decline.

The outcome of this will depend upon the plans and actions of the stakeholders of said tourism development project.

Complete rejuvenation can occur through major redevelopments. Perhaps new attractions are added, sustainable tourism approaches are adopted or there is a change in the target market.

Modest rejuvenation may occur with some smaller adjustments and improvements to the general tourism infrastructure and provision.

If changes do not occur, there may be a slow continuation of tourism decline.

In severe circumstances, there may be a rapid decline of the tourism provision. This is likely due to a life-changing event such as war, a natural disaster or a pandemic.

What happens after complete decline?

Sadly, the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in many tourism destinations and attractions experiencing the drastic decline identified in Butler’s most pessimistic scenario.

These areas will likely either experience one of two possible outcomes-

1- Tourism infrastructure will be used for alternative means. Hotels may become retirement homes and tourism attractions will be replaced with non-tourism facilities. The area may become run down and impoverished as a result of the economic loss.

2- Tourism development will start again. Many destinations have taken this opportunity to re-evaluate and reimagine their tourism infrastructure. Improvements can be made and more sustainable practices can be adopted. The destination will start again at the beginning of Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle.

Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model is great because it provides simplistic theoretical guidance to tourism stakeholders.

Those who are just starting out can use this model to plan their tourism infrastructure and development. It encourages critical thinking and long-term thinking.

However, Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model can also be criticised for its simplicity.

Without sufficient knowledge and training, tourism stakeholders may not understand this model and therefore may not adequately utilise it.

The linear approach taken with this module does not account for unique and unaccounted for occurrences. In other words, not every destination or attractions may follow these stages in this way.

Lastly, being developed back in 1980, Butler’s model fails to account for many of the complexities of today’s travel and tourism industry. The biggest downfall is the redundancy of references to sustainability.

Sustainability is at the core of everything that we do in today’s world, so it is perhaps outdated thinking to assume that all destinations will reach consolidation in the way that it is represented in Butler’s model.

Wow, who knew I would be able to write 1500 all about Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model? Well, in actual fact, I could easily write another 1500! This theory is an important part of the tourism curriculum and is important for travel and tourism students to understand, as well as a variety of tourism stakeholders.

Want to learn more? Follow along on social media or subscribe to my newsletter for conceptual and practical travel tips and information!

Liked this article? Click to share!

Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) and the Quality of Life (QOL) of Destination Community Revisited

- First Online: 24 September 2023

Cite this chapter

- Muzaffer Uysal 11 ,

- Eunju Woo 12 &

- Manisha Singal 13

Part of the book series: International Handbooks of Quality-of-Life ((IHQL))

333 Accesses

This chapter examines the connection between the tourism (TALC) and its effects on the quality of life (QOL) of destination communities. We posit that as destinations go through structural changes over time, the extent to which the dynamics of change affect the QOL of the resident community vary with the stages of the life cycle. The chapter consists of four major sections. After a brief introduction, the first section presents the concept of TALC and describes the development phases and the indicators that help understand tourism area development. The second section provides a brief discussion on the impact of tourism on the community in relation to TALC, which is then followed by the third section which focuses on the adjustment to change and maintaining the QOL of the community. Section four reviews the literature to support the relation between TALC and QOL of communities. The chapter ends with describing critical issues for future research, outlining some of the difficulties moving forward, and formulating relevant policy implications that may help the researchers and destination management organizations to further examine important issues that surround TALC and QOL connections.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Akis, S., Peristianis, N., & Warner, J. (1996). Residents’ attitudes to tourism development: The case of Cyprus. Tourism Management, 17 (7), 481–494.

Article Google Scholar

Allen, L. R., Hafer, H. R., Long, P. T., & Perdue, R. R. (1993). Rural resident attitudes toward recreation and tourism development. Journal of Travel Research, 31 (4), 27–33.

Allen, L. R., Long, P. T., Perdue, R. R., & Kieselbach, S. (1988). The impacts of tourism development on residents’ perceptions of community life. Journal of Travel Research, 26 (1), 16–21.

Andereck, K. L. (1995). Environmental consequences of tourism: A review of recent research. In Linking tourism, the environment, and sustainability. Annual meeting of the national recreation and park association (pp. 77–81).

Google Scholar

Andereck, K. L., & Vogt, C. A. (2000). The relationship between residents’ attitudes toward tourism and tourism development options. Journal of Travel Research, 39 , 27–36.

Ap, J. (1992). Residents’ perceptions on tourism impact. Annals of Tourism Research, 19 , 665–690.

Bachleitner, R., & Zins, A. H. (1999). Cultural tourism in rural communities: The residents’ perspective. Journal of Business Research, 44 , 199–209.

Beardsley, M. E. G. H. A. N. (2016). Quality of life, the tourism area life cycle and sustainability: A case of Cuba. In Sustainable island tourism: Competitiveness and Quality of Life (pp. 93–105). CAB International.

Chapter Google Scholar

Berbekova, A., Uysal, M., & Assaf, A. G. (2021). Toward an assessment of quality of life indicators as measures of destination performance. Journal of Travel Research . https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875211026755

Birsen, A. G., & Bilim, Y. (2019). A comparative life cycle analysis of two mass tourism destinations in Turkey. Journal of Tourism and Gastronomy Studies, 1290 , 1313.

Boyd, S. W. (2006). The TALC model and its application to national parks: A Canadian example. In C. Cooper, C. M. Hall, & D. Timothy (Series Eds.), & R. W. Butler (Vol. Ed.), The tourism area life cycle: Vol. 1. Applications and modifications (pp. 119–138). Channel View Publications.

Brunt, P., & Courtney, P. (1999). Host perceptions of sociocultural impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 26 , 493–515.

Budruk, M., & Phillips, R. (2011). Quality of life community indicators for parks recreation and tourism management . Springer.

Book Google Scholar

Butler, R. W. (1980). The concept of a tourism areas cycle of evaluation: Implications for management of resources. Canadian Geographer, 24 (1), 5–12.

Butler, R. W. (2004). The tourism area lifecycle in the twenty first century. In A. A. Lew, Butler, R. W. (Eds.). (2006). The tourism area life cycle (vol. 1). Channel view publications.

Cornell, D. A. V., Tugade, L. O., & De Sagun, R. (2019). Tourism quality of life (TQOL) and local residents’ attitudes towards tourism development in Sagada. Philippines. Revista Turismo & Desenvolvimento, 31 , 9–34.

Diedrich, A., & Garcia-Buades, E. (2009). Local perceptions of tourism as indicators of destination decline. Tourism Management, 30 , 512–521.

Doğan, Z. H. (1989). Forms of adjustment: Sociocultural impacts of tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 16 , 216–236.

Doğan, Z. H. (2004). Turizmin Sosyo-Kültürel Temelleri . Detay Yayıncılık.

Doxey, G. V. (1976). When e nough’s enough : The natives are restless in old Niagara. Heritage Canada, 2 (2), 26–27.

England, J. L., & Albrecht, S. L. (1984). Boomtowns and social disruption. Rural Sociology, 49 , 230–246.

Formica, S., & Uysal, M. (1996). The revitalization of Italy as a tourist destination. Tourism Management, 17 (5), 323–331.

Gursoy, D., Jurowski, C., & Uysal, M. (2002). Resident attitudes: A structural modeling approach. Annals of Tourism Research, 29 (1), 79–105.

Haralambopoulos, N., & Pizam, A. (1996). Perceived impacts of tourism: The case of Samos. Annals of Tourism Research, 23 , 503–526.

Haywood, K. M. (1986). Can the tourist-area lifecycle be made operational? Tourism Management, 7 (3), 154–167.

Hovinen, G. R. (2002). Revisiting the destination model. Annals of Tourism Research, 29 (1), 209–230.

Hu, R., Li, G., Liu, A., & Chen, J. L. (2022). Emerging research trends on residents’ quality of life in the context of tourism development. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 10963480221081382 , 109634802210813.

Johnson, J. D., & Snepenger, D. J. (1993). Application of the tourism life cycle concept in the greater Yellowstone region. Journal of Society & Natural Resources, 6 (2), 127–148.

Johnson, J. D., Snepenger, D. J., & Akis, S. (1994). Residents’ perceptions of tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research, 21 (3), 629–642.

Jurowski, C., & Brown, D. O. (2001). A comparative of the views of involved versus noninvolved citizens on quality of life and tourism development issues. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 25 (4), 355–370.

Jurowski, C., Daniels, M., & Pennington-Gray, L. (2006). The distribution of tourism benefits. In G. Jennings & N. P. Nickerson (Eds.), Quality tourism experiences (pp. 192–207). Elsevier.

Juvan, E., Podovšovnik, E., Lesjak, M., & Jurgec, J. (2021). A Destination’s social sustainability: Linking tourism development to residents’ quality of life. Academica Turistica-Tourism and Innovation Journal, 14 (1), 39–52.

Kim, H., Kim, Y. G., & Woo, E. (2021). Examining the impacts of touristification on quality of life (QOL): The application of the bottom-up spillover theory. The Service Industries Journal, 41 (11–12), 787–802.

Kim, K., Uysal, M., & Sirgy, J. (2003, June). The effects of tourism impacts upon quality of life of residents in the community. TTRA’s 34 th Annual Conference Proceedings, pp. 16–20. St. Louis, MO, USA.

Ko, D., & Stewart, W. P. (2002). A structural equation model of residents’ attitudes for tourism development. Tourism Management, 23 , 521–530.

Krannich, R. S., Berry, E. H., & Greider, T. (1989). Fear of crime in rapidly changing rural communities: A longitudinal analysis. Rural Sociology, 54 , 195–212.

Liu, J. C., & Var, T. (1986). Resident attitudes toward tourism impacts in Hawaii. Annals of Tourism Research, 13 (2), 193–214.

Long, P. T., Perdue, R., & Allen, L. (1990). Rural resident tourism perceptions and attitudes by community level of tourism. Journal Travel Research, 28 , 3–9.

McCool, S., & Martin, S. (1994). Community attachment and attitudes towards tourism development. Journal of Travel Research, 32 (3), 29–34.

Meng, F., Li, X., & Uysal, M. (2010). Tourism development and regional quality of life: The case of China. Journal of China Tourism Research, 6 , 164–182.

Modica, P., & Uysal, M. (Eds.). (2016). Sustainable Island tourism: Competitiveness and quality of life . CABI.

Mok, C., Slater, B., & Cheung, V. (1991). Residents’ attitudes towards tourism in Hong Kong. Journal of Hospitality Management, 10 , 289–293.

Odum, C. J. (2020). The implication of TALC to tourism planning and development in the global south: Examples from Nigeria. Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management, 8 (2), 68–86.

Oliveros Ocampo, C. A., Virgen Aguilar, C. R., & Chávez Dagostino, R. M. (2019). Approaches of research on the life cycle of the tourist area. Turismo y Sociedad, 24 , 51–75.

Oppermann, M. (1998). What is new with the resort cycle? Tourism Management, 19 (2), 179–180.

Perdue, R. R., Long, P. T., & Allen, L. R. (1990). Resident support for tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research, 17 (4), 586–599.

Perdue, R. P., Long, P. T., & Kang, Y. S. (1999). Boomtown tourism and resident quality of life: The marketing of gaming to host community residents. Journal of Business Research, 44 , 165–177.

Peters, M., & Schuckert, M. (2014). Tourism entrepreneurs’ perception of quality of life: An explorative study. Tourism Analysis, 19 (6), 731–740.

Petrevska, B., & Collins-Kreiner, N. (2017). A double life cycle: Determining tourism development in Macedonia. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 15 (4), 319–338.

Pizam, A., & Pokela, J. (1985). The perceived impacts of casino gambling on a community. Annals of Tourism Research, 12 , 147–165.

Powers, T. M. (1988). The economic pursuit of quality . M. E. Sharpe.

Ramkissoon, H. (2016). Place satisfaction, place attachment and quality of life: Development of conceptual framework for Island destinations (pp. 106–116). Competitiveness and Quality of Life.

Ridderstaat, J., Croes, R., & Nijkamp, P. (2016). A two-way causal chain between tourism development and quality of life in a small Island destination: An empirical analysis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24 (10), 1461–1479.

Roehl, W. S. (1999). Quality of life issues in a casino destination. Journal of Business Research, 44 , 223–229.

Ryan, C., Scotland, A., & Montgomery, D. (1998). Resident attitudes to tourism development- a comparative study between the Rangitikei, New Zealand and Bakewell, United Kingdom. Progress in Tourism and Hospitality Research, 4 (2), 115–130.

Seo, K., Jordan, E., Woosnam, K. M., Lee, C. K., & Lee, E. J. (2021). Effects of emotional solidarity and tourism-related stress on residents’ quality of life. Tourism Management Perspectives, 40 , 100874.

Singal, M., & Uysal, M. (2009). Resource commitment in destination management: The case of Abingdon, Virginia. Tourism Review, 57 (3), 329–344.

Sirgy, M. J., Widgery, R. N., Lee, D., & Yu, G. B. (2010). Developing a measure of community Well-being based on perceptions of impact in various life domains. Social Indicators Research, 96 , 295–351.

Toh, R. S., Khan, H., & Koh, A. (2001). A travel balance approach for examining tourism area life cycles: The case of Singapore. Journal of Travel Research, 39 , 426–432.

Tooman, L. A. (1997). Applications of the life-cycle model in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 24 (1), 241–234.

Tosun, C. (2002). Host perceptions of impacts: A comparative tourism study. Annals of Tourism Research, 29 , 231–253.

Tye, V., Sirakaya, E., & Sonmez, S. (2002). Residents’ attitudes toward tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research, 29 (3), 668–688.

Upchurch, R. S., & Teivane, U. (2000). Resident perceptions of tourism development in Riga, Latvia. Tourism Management, 21 , 499–507.

Uysal, M., & Sirgy, M. J. (2019). Quality-of-life indicators as performance measures. Annals of Tourism Research, 76 (2019), 291–300.

Vargas-Sánchez, A., Plaza-Mejía, M., & Porras-Bueno, N. (2009). Understanding residents’ attitudes toward the development of industrial tourism in former mining. Journal of Travel Research, 47 (3), 373–387.

Whitfeild, J. (2009). The cyclical representation of the UK conference sector’s life cycle: The use of refurbishments as rejuvenation triggers. Tourism Analysis, 14 , 559–572.

Woo, E., Uysal, M., & Joseph Sirgy, M. (2019). What is the nature of the relationship between tourism development and the quality of life of host communities? In Best practices in hospitality and tourism marketing and management (pp. 43–62). Springer.

Woo, E., Uysal, M., & Sirgy, M. J. (2018). Tourism impact and stakeholders’ quality of life. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 42 (2), 260–286.

Yu, C. P., Cole, S. T., & Chancellor, C. (2016). Assessing community quality of life in the context of tourism development. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 11 (1), 147–162.

Yu, C. P., Cole, S. T., & Chancellor, C. (2018). Resident support for tourism development in rural midwestern (USA) communities: Perceived tourism impacts and community quality of life perspective. Sustainability, 10 (3), 802.

Zhong, L., Deng, J., & Xiang, B. (2008). Tourism development and the tourism area life-cycle model: a case study of Zhangjiajie national forest park, China. Tourism Management, 29 , 841–856.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, MA, USA

Muzaffer Uysal

College of Business Administration, Pukyong National University, Busan, Republic of Korea

Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA

Manisha Singal

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Muzaffer Uysal .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Hospitality & Tourism Management, Isenberg School of Management, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, USA

Department of Marketing, Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA

M. Joseph Sirgy

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Uysal, M., Woo, E., Singal, M. (2023). Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) and the Quality of Life (QOL) of Destination Community Revisited. In: Uysal, M., Sirgy, M.J. (eds) Handbook of Tourism and Quality-of-Life Research II. International Handbooks of Quality-of-Life. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31513-8_19

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31513-8_19

Published : 24 September 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-31512-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-31513-8

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

The Tourism Area Life Cycle

Review, relevance and revision.

- Edited by: Richard Butler

- X / Twitter

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

- Language: English

- Publisher: Channel View Publications

- Copyright year: 2024

- Main content: 362

- Keywords: Management & management techniques ; Tourism industry

- Planned Publication: August 13, 2024

- ISBN: 9781845419141

The 6 phases of a tourist destination’s life cycle

What is the life cycle of a tourist destination according to Butler?

Life cycle graph of a tourism destination.

Since the mid-20th century , thanks to factors such as the emergence of commercial flights, higher household incomes and the regularization of paid vacations, among others, tourism has become a mass phenomenon .

Until then, this was an activity that had been carried out empirically, causing some tourism projects to become unsustainable over time. In order to have a guide that would allow planners and developers to anticipate problems and create alternative or contingency plans, the need to create a model with the different stages of development of a tourist destination was considered.

The great beneficiaries of this model on the phases through which a tourist destination moves through are the tour operators or wholesalers , who determine how to sell a tourist package taking into account the specific phase of a destination’s development cycle.

There are many examples of wholesale travel agencies that analyze, research and apply these studies to increase the profitability of their products.

Understanding the tourism life cycle is crucial for stakeholders in the tourism industry . This concept not only helps in recognizing the current stage of a destination but also in strategizing for sustainable growth and development. As tourism evolves from a niche activity to a mass phenomenon, recognizing each phase within the tourism life cycle becomes a pivotal tool for effective management and planning.

To answer this question, Richard Butler, Emeritus Professor at the Strathclyde Business School in Glasgow, created the Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) in 1980. In it, he essentially equates the evolution of destinations with that of products or services .

Butler seeks to demonstrate that tourism is not a static process, but that it evolves or declines according to factors such as destination discovery, visitor flow, support from authorities, the relationship between tourists and locals, infrastructure, etc.

To create his model, Butler used a number of theories related to other fields , such as sociology, biology and the life cycle of products in international commerce. The TALC has become a widely used tool as a theoretical foundation for research and analysis of the tourism sector.

According to Butler’s model, tourism destinations go through six evolutionary phases , although it is important to mention that not all destinations invariably go through each of them.

Exploration

In this first phase the destination receives few visitors , lured by natural attractions, such as pristine beaches; or by its culture, such as handicrafts or ethnic groups. It is precisely the lack of infrastructure that attracts the attention of the first tourists. The physical environment and its population are little affected by the presence of visitors, and the economic benefits are limited. There is usually a positive relationship between locals and tourists.

Involvement

In this phase, local people start businesses aimed at tourists , such as guesthouses, restaurants or tours. Investors show interest in developing future projects.

Governments are pressured by the need to develop tourism infrastructure. It begins with the promotion of the destination, which gives rise to the phenomenon of seasonality.

Development

The flow of visitors increases, as well as the digital promotion of the destination . Tour operators and tourism promoters take the opportunity to launch their promotional campaigns advertising the destination on travel agencies’ social networks in order to reach a larger target audience. At this stage, infrastructure grows , especially related to transportation. Natural and cultural attractions may become less important due to the emergence of new artificial attractions .

Occasionally, control of the tourism market passes from local hands to external companies . The standard of living of the inhabitants generally improves, however, the relationship they have with tourists can become strained.

The development phase in the tourism life cycle is a critical turning point, where effective management can significantly influence the future trajectory of a destination . At this juncture, understanding the intricacies of the tourism life cycle allows for the implementation of strategies that balance growth with sustainability. This ensures that the destination remains attractive and viable for future visitors while preserving its natural and cultural assets.

Consolidation

During this stage growth slows, but continues to rise . This may be intentional, to preserve the exclusivity of services, or not.

Tourism becomes fundamental for the economy of the area, generally being its main source of income . The aim is to increase the stay of visitors, their per capita expenditure and to deseasonalize visits.

Due to foreign companies setting up in the region, there is a drain of capital. Other negative effects may be felt, such as wear and tear on the infrastructure and dissatisfaction of the local population with tourism.

During this phase, tourism demand begins to decline and stagnate . The destination is no longer fashionable, so an alternative or conservative market is sought. Economic, environmental and social problems arise.

As destinations reach the stagnation phase and face challenges in attracting new visitors, harnessing the power of data and insights is essential .

Dive into our in-depth analysis on leveraging Google Travel Insights for strategic tourism growth and innovation, where we explore the transformative power of data in the tourism industry.

Decline or rejuvenation

In the last stage there are two scenarios: decline, where the destination loses affluence and cannot compete with other destinations that are in earlier stages. When this happens, the tourism infrastructure is usually put to another use.

This decline is usually gradual, but can also occur abruptly and unexpectedly due to external events (for example, the COVID-19 crisis in 2020, considered by the UNWTO as the worst year in history for tourism).

Another course that a destination can take after stagnation is rejuvenation , where efforts are combined to shift the destination’s focus, become more sustainable and target other markets.

Lead the Change in Tourism Industry

Optimize with Mize Fintech Solutions. Thrive in every stage of the hotel booking process.

Butler’s graph is a linear model in which the different stages are plotted along X and Y axes, representing the number of visitors and time, respectively.

A great number of tourist sites have been analyzed according to the Butler model, such is the case with a 2009 study carried out by Carlos Rogelio Virgen Aguilar on Puerto Vallarta. Broadly speaking, these were his conclusions:

Several factors influenced the discovery of Puerto Vallarta, undoubtedly an important one was that it became the location for the 1964 film “The Night of the Iguana” , directed by John Houston.

In the following years Puerto Vallarta experienced a boom from 2,687 hotel units in 1975 to 10,029 in 1992. An international airport was built in 1970 and the tourist infrastructure was improved.

After this stage, where the average annual rate was 15.2%, growth slowed down and even decreased , but showed a slight increase from 2001 to 2005, with condominiums being the predominant choice (non-hotel offering) .

After 2005, no new attractions were created to attract a greater number of tourists , nor did they seek to increase per capita spending. Undoubtedly, the offer of condominiums affected the hotel sector, while the neighboring destination, Nuevo Vallarta, attracts a large part of the region’s tourism.

Butler’s model is an important analysis tool that allows for the future planning of a tourist destination and the development of action plans that will allow it to reinvent itself once it goes beyond the consolidation phase.

As we wrap up our discussion on the life cycle of tourist destinations, understanding the crucial role of expert management in these phases is paramount. Delve into our dedicated exploration to grasp the full scope of the benefits of a travel management company , where we dissect their pivotal role and offer a comprehensive view of their operational strategies and advantages.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Yay you are now subscribed to our newsletter.

Marc Truyols has a degree in Tourism from the University of the Balearic Islands. Marc has extensive experience in the leisure, travel and tourism industry. His skills in negotiation, hotel management, customer service, sales and hotel management make him a strong business development professional in the travel industry.

Mize is the leading hotel booking optimization solution in the world. With over 170 partners using our fintech products, Mize creates new extra profit for the hotel booking industry using its fully automated proprietary technology and has generated hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue across its suite of products for its partners. Mize was founded in 2016 with its headquarters in Tel Aviv and offices worldwide.

Related Posts

Opening Up to New Markets While Maintaining the Brand

8 min. Case study of adapting the Mize brand for the East Asia market Making a cultural adjustment – finding the balance between global and local The process of growing globally can be very exciting and, at the same time, challenging. Although you are bringing more or less the same products and vision, the way […]

Travel Niche: What It Is, How to Leverage It, Case Studies & More

14 min. Niche travel is one of the few travel sectors that have maintained their pre-COVID market growth. By catering to specific traveler segments, niche travel developed products around adventure travel, eco-tourism, LGBTQ+ travel, and wellness retreats. Take adventure tourism as only one segment of the niche tourism market. In 2021, it reached 288 billion […]

4 Lessons You Can Learn From the Best Tourism Campaigns

13 min. Businesses in the tourism industry rely heavily on marketing to generate leads and boost conversion rates. Tourism marketing is as old as tourism itself – and it always reflects the destination and service benefits relevant to the current travelers’ needs, wants, and expectations. In other words, tourism campaigns must constantly move forward, and […]

Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model (TALC)

Tourism is one of the biggest industries in the world. It is a very dynamic industry and changing constantly. Tourist attractions are often fragile and therefore require careful management.

Therefore, a good number of writers have initiated conversations concerning the carrying capacity and sustainability of attractions over the years. One of the most prominent ones is Professor Richard W. Butler, a geographer and professor of tourism. He came up with a model called Tourism Area Life Cycle Model (TALC) which is based on Product Life Cycle concept. The model can be used to study tourist attractions to see how they change over time.

Stages in Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model (TALC)

Butler’s model for the life cycle of a tourist destination has a number of stages as follows:

Photo credit: Pinterest

Exploration in Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model (TALC)

Exploration is the first stage of the model. It is a stage where a very limited number of visitors visit the area. Visitors usually make their individual travel arrangements, and the pattern of visitation is irregular. The area may have attracted the visitors, usually the non-local ones due to its cultures and scenic beauty.

In this stage, local people are not involved in money making from tourist-related activities, and therefore, enjoy a very little or no economic benefits from their interactions with the tourists. Some parts of Canadian Arctic and Latin America can be used as examples of the exploration stage. Likewise, some sites in Bangladesh, Pakistan, India, and Saudi Arabia can also be considered in this regard.

Involvement in Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model (TALC)

Involvement is the stage where the number of people visiting the area is increasing. Therefore, residents now see economic benefits in providing some facilities such as food, accommodation, guides, and transport to the tourists.

As the stage progresses, some marketing efforts to take the attraction out there are in place and a recognised tourist season is somehow realised. This stage puts pressure on local and national authorities to contribute to the development of the area by providing and improving transport infrastructure and other facilities for visitors. Examples of this stage include less developed islands and less accessible areas in many parts of the world.

Development in Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model (TALC)

Development is a stage where the area becomes widely recognised as a tourist attraction, partly because of heavy advertising and promotional efforts. As the attraction is becoming known and popular, investors and tourist companies see opportunities for financial gains.

Consequently, more cultural attractions and facilities such as big hotels, restaurants, bars, arenas, and convention centres are developed to supplement the original attraction. In this stage, particularly during the holiday season, tourists may start outnumbering the local people.

Local people are most likely to lose control of the development of the area. Examples of this stage includes some developed islands and areas in Mexico, Turkey, India, Philippines, Maldives, Indonesia, north and west African coasts, and many other places.

Consolidation in Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model (TALC)

Consolidation is the stage where the numbers of visitors are higher than the permanent residents. The local economy is dominated by tourism at this stage. Tourism businesses will push for further expansion of the attraction.

However, some local people, particularly those who are not involved in tourism development, will be unhappy and oppose tourism activities due to their impact on socio-cultural environment. Examples of this stage can be found in some areas in Barcelona (Spain), Goa (India), Marina Bay Sands and Resorts World Sentosa (Singapore), St. Kitts and Nevis island (the Caribbean) and many others.

Stagnation in Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model (TALC)

Stagnation as the name suggests, is the stage where many aspects of an attraction have reached maximum capacity and cannot grow any further. The local environment is polluted, and many species can no longer survive.

In this stage, the attractions depend heavily on repeat visitation and substantial marketing efforts are required to keep the business going. Examples include some attractions in Singapore which had a relatively stagnant performance last several years.

Decline in Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model (TALC)

After the stagnation stage, the area may face different possibilities. One of the possibilities is decline where the area is no longer able to compete with newer attractions. This decline stage is characterised by weekend and day trips as the attraction has lost its appeal.

As tourist facilities disappear at this stage, the involvement of permanent residents in tourism may increase due to the availability of cheaper facilities in declining market conditions. However, the area may completely lose its tourist function eventually.

Examples of decline include but of course not limited to Guaíra Falls (Paraguay, Brazil), Sutro Baths (San Francisco), Porcelain Tower of Nanjing (China), Chacaltaya Glacier (Bolivia), and Malta’s Royal Opera House of Valletta (Johanson, 2022).

Rejuvenation in Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model (TALC)

Another possibility is rejuvenation of the area. However, for rejuvenation to happen, the attraction requires a complete change (Butler, 1980). This change can happen in two main ways as suggested by Butler.

Firstly, new man-made attractions can be introduced. Secondly, the attraction can take advantage of the previously untapped natural resources. Support for local and national governments may be necessary at this stage of the cycle. Santiago (Chile) is a good example of rejuvenation which has experienced a major transformation in the last few years.

Summary of Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model (TALC)

In conclusion, Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model (TALC) is a useful tool to understand the stages that a tourist attraction goes through in its life. It helps tourism planners and developers examine how tourist resorts can change over time in response to the changing demands of the tourist industry.

We hope the article ‘Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model (TALC)’ has been helpful. Please share the article link on social media to help us grow. You may also like reading:

PESTEL analysis of the tourism industry

Ansoff Matrix in Apple Inc.

BCG matrix – definition and how to use BCG Matrix

Other relevant articles for you are:

Differences between tourism and hospitality

Ecotourism – definition and characteristics

Factors affecting tourism demand

PESTEL analysis of China

SWOT analysis of Hilton Worldwide

Marketing mix of Facebook

Importance of a business plan (Benefits of business planning)

Decision making unit (DMU)

Last update: 16 January 2023

References:

Butler, R. W. (1980) The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: implications for management of resources, The Canadian Geographer, 24, pp. 5-12

Johanson, M. (2015) The best tourist attractions that no longer exist, available at: https://edition.cnn.com/travel/article/attractions-no-longer-exist/index.html (accessed 02 July 2019)

Photo credit: Pinterest

Author: M Rahman

M Rahman writes extensively online and offline with an emphasis on business management, marketing, and tourism. He is a lecturer in Management and Marketing. He holds an MSc in Tourism & Hospitality from the University of Sunderland. Also, graduated from Leeds Metropolitan University with a BA in Business & Management Studies and completed a DTLLS (Diploma in Teaching in the Life-Long Learning Sector) from London South Bank University.

Related Posts

How to be a good team player, competitive advantage for tourist destinations, advantages and disadvantages of snowball sampling.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Policy

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About Policy and Society

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Tourism Policy and Planning: Evaluating the Life Cycle Model in Relation to Queensland and Hawaii

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Anthony van Fossen, George Lafferty, Tourism Policy and Planning: Evaluating the Life Cycle Model in Relation to Queensland and Hawaii, Policy and Society , Volume 16, Issue 1, December 1998, Pages 50–66, https://doi.org/10.1080/10349952.1998.11876689

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This paper examines the most influential model of tourism development, the life cycle model, which has defined a ‘normal science’ of evolution for tourism destinations. The model is internally coherent, logical, easily intelligible and was used extensively as a guide to predicting development. For all destinations it postulates a path of steady growth until stagnation is reached. The model's widespread influence has discouraged policy and planning prior to stagnation. This paper illustrates the model's limitations, through a comparative analysis of tourism development in Queensland and Hawaii. Tourism growth in actual destinations does not support the model's predictions, in that some of the most attractive, but undeveloped destinations, have shown limited growth, while there are no indications of decline in established ‘mass’ destinations. Tourism growth in undeveloped areas is not inevitable, nor need developed destinations eventually stagnate. The paper argues that there is no automatic developmental progression. At all levels of development there are crisis points requiring coherent policy implementation if sustainable tourism growth is to be achieved.

Australian Bureau of Statistics . 1997 . Queensland Year Book 1997 . Brisbane , Commonwealth Government .

Google Scholar

Google Preview

Britton , S.G. 1991 . ‘Tourism, capital, and place: towards a critical geography of tourism’ . Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 9 , 451 – 478 .

Butler , R. W. 1980 . ‘The concept of a tourist cycle of evolution: implications for management resources’. Canadian Geographer 24 , 512 .

Butler , R. W. 1992 . ‘Alternative tourism: the thin edge of the wedge’. In Tourism Alternatives , ed. V. L. Smith and W. R. Eadington , Philadelphia : University of Pennsylvania Press .

Butler , R.W. and Waldbrook , L.A. 1991 . ‘A new planning tool: the tourism opportunity spectrum’ . Journal of Tourism Studies 2 ( 1 ), 2 – 14 .

Choy , D. J. L. 1992 ‘Life cycle models for Pacific Island destinations’ . Journal of Travel Research 30 ( 3 ), 26 – 31 .

Connell , J. 1993 . ‘Bali revisited: death, rejuvenation and the tourist cycle’ . Environment and Planning D 11 , 641 – 661 .

Cooper , C. and S. Jackson 1989 . ‘Destination life cycle: the Isle of Man case study’ . Annals of Tourism Research 16 ( 3 ), 377 – 398 .

Debbage , K. 1990 . ‘Oligopoly and the resort cycle in the Bahamas’ . Annals of Tourism Research 17 ( 4 ), 513 – 527 .

Getz , D. 1983 . ‘Capacity to absorb tourism: concepts and implications for strategic planning’ . Annals of Tourism Research 10 , 239 – 263 .

Getz , D. 1992 ‘Tourism planning and the destination life cycle’ . Annals of Tourism Research 19 ( 4 ), 752 – 770 .

Hart , C. W. , G. Casserly and M. J. Lawless . 1984 . ‘The product life cycle: how useful?’ . Cornell Journal of Hotel and Restaurant Administration 25 ( 3 ), 54 – 63 .

Hawaii Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism . 1997.1996 Annual Research Report, Hawaii Visitors' and Convention Bureau. Honolulu , DBEDT .

Hawaii Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism . 1998 . 1997 Annual Research Report, Hawaii Visitors' and Convention Bureau. Honolulu , DBEDT .

Haywood , K. M. 1986 . ‘Can the tourist-area life cycle be made operational?’ . Tourism Management 7 ( 3 ), 154 – 167 .

Haywood , K. M. 1992 . ‘Revisiting the resort cycle’ . Annals of Tourism Research 19 ( 2 ), 351 – 354 .

Hovinen , G. R. 1982 . ‘Visitor cycles: outlook in tourism in Lancaster County’ . Annals of Tourism Research 9 , 565 – 583 .

Ioannides , Dimitri 1992 . ‘Tourism development agents: the Cypriot resort cycle’ . Annals of Tourism Research 19 ( 4 ), 711 – 731 .

Kent , N. 1992 . Hawaii: Islands under the Influence , Honolulu , University of Hawaii Press .

Kermath , B. M. and R. N. Thomas . 1992 . ‘Spatial dynamics of resorts: Sosua, Dominican Republic’ . Annals of Tourism Research 19 , 173 – 190 .

Lafferty , G. and A. van Fossen . 1996 . ‘Policy's uncertain future: the case of tourism’ . Culture and Policy 7 ( 2 ), 78 – 86 .

Markusen , A.R. 1985 . Profit cycles, oligopoly and regional development. Cambridge, MA . MIT Press .

Martin , B. S. and M. Uysal . 1990 . ‘An examination of the relationship between carrying capacity and tourism life cycle: management and policy implications’ . Journal of Environmental Management 31 , 327 – 333 .

Pearce , P.L. 1991 . ‘Visitor centres and their functions in the landscape of tourism’. In Visitor Centres: Exploring New Territory , ed. G. Moscardo and K. Hughes . Townsville , James Cook University of North Queensland .

Pearce , P.L. ( 1993 ) ‘Fundamentals of tourist motivation’. In Tourism Research , ed. D.G. Pearce and R.W. Butler . London , Routledge .

Pearce , P.L. , G. Moscardo and G. F. Ross . 1991 . ‘Tourism impact and community perception: an equity-social representational perspective’ . Australian Psychologist 26 ( 3 ), 147 – 152 .

Plog , S.C. 1991 . Leisure Travel: Making it a Growth Market…Again! New York , John Wiley and Sons .

Poon , A. 1988 . ‘The future of Caribbean tourism: a matter of innovation’ , Tourism Management 9 , 213 – 220 .

Priestley , Gerda and Lluìs Mundet . 1998 . ‘The post-stagnation phase of the resort cycle’ . Annals of Tourism Research 25 ( 1 ), 85 – 111 .

Prosser , G. 1995 . ‘Tourist destination life cycles: progress, problems and prospects’. In Proceedings of the National Tourism and Hospitality Conference , ed. R.N. Shaw . Melbourne , Council for Australian University Tourism and Hospitality Education .

Shaw , G. and A. M. Williams . 1994 . Critical Issues in Tourism: a Geographical Perspective , Oxford , Blackwell .

Smith , R. A. 1992 . ‘Beach resort evolution: implications for planning’ . Annals of Tourism Research 19 , 304 – 322 .

Van Fossen , A. and G. Lafferty . 1997 . ‘Tourism development in Queensland and Hawaii: a comparative study’ . Queensland Review 4 ( 1 ), 1 – 11 .

Van Fossen , A. and G. Lafferty . 1998 . ‘Analysing the dynamics of tourism growth: South Korean visitors to Hawaii and Queensland’ . Journal of Australian Studies 5 ( 1 ), 3 – 12 .

Vernon , R. 1966 . ‘International investment and international trade in the product cycle’ . Quarterly Journal of Economics 80 ( 2 ), 190 – 207 .

Weaver , D. B. 1990 . ‘Grand Cayman Island and the resort cycle concept’ . Journal of Travel Research 29 ( 2 ), 9 – 15 .

World Tourism Organisation . 1997 . Yearbook of Tourism Statistics. Madrid , World Tourism Organisation .

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1839-3373

- Print ISSN 1449-4035

- Copyright © 2024 Darryl S. Jarvis and M. Ramesh

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

Butler's Tourism Area Life Cycle and Its Expansion to the Creative Economy

2017, The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Travel and Tourism

In 1980, R. W. Butler published his tourism area cycle of evolution model graphing a correlation of number of tourists on the y-axis and time on the x-axis. Although a location’s capacity for number of tourists and the specific number of sustainable years may vary from location to location, Butler proposed that every tourist location evolves through a common set of stages: exploration, involvement, development, consolidation, stagnation, and then some variation of rejuvenation or decline (see Figure 1). Butler’s model frames the resources that enable a region to become a tourist destination as finite and ultimately exhaustible. One adaptation of Butler’s tourism area cycle of evolution is to transfer similar concepts to the creative economy. A tourism economy plays hand in hand with the creative economy, and one can feed the other. Like Butler’s tourism areas, artists and artisans, communities, villages, towns, cities, and counties also experience economic life cycles. This creative economy life cycle assumes a circular posture that, although it seems more optimistic than Butler’s almost inevitable decline, recognizes that time is a variable scale and can be framed in more geologic than human scales. The creative economy life cycle parallels Butler’s involvement, exploration, development, consolidation, stagnation, and decline with stages moving from prosperity to self-preservation to crisis to opportunity.

Related Papers

Rod Caldicott

Tourism Management

Josep A. Ivars Baidal

Journal of Geography, Politics and Society

Dejan Iliev

The study provides a historical and contextual analysis of the evolution of tourism in Macedonia. The time scope is defined as the period between 1991 and in 2018. The study investigates the tourism development in Macedonia in the post-socialist period of the country, using the Butler (1980) Tourist Area Life Cycle (TALC) model as an analytical tool. The model provides a framework to explain the complex processes of the development and changes in tourism in the country over the years. For this purpose, an analysis of secondary data sources is implemented to find the changes in the evolutionary stages of tourism development. The findings show that tourism in Macedonia is in a stage of development, and that it has not yet reached the consolidation stage. Lastly, the study offers a better understanding of how tourism in Macedonia is changing in the complex post-socialist period.

WONDIRAD Amare Nega (Ph.D.) , yihalem kebete

Visitor management becomes a core element of sustainable destination management in the wake of a continuously growing tourism sector. The current study examines how effective visitor management contributes to sustainable tourism destination development employing the triple-bottom-line concept. The study adopts a qualitative research approach with an exploratory design and collects qualitative data from purposively selected participants. Data collection took place between December 2017 and April 2018. Research findings inform that proper visitor management practices further strengthen sustainable tourism destination development. Even though, inadequate, visitor management is currently practiced in Zegie Peninsula. However, ensuring broad-based tourism stakeholder engagement to sustain the proper development of tourism remains a challenge. This study advances our understanding of the inextricable links among visitor management practices, stakeholder engagement, and sustainable destination development. Visitor management concepts compatible with sustainable tourism development are suggested along with study limitations and opportunities for future research.

International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research

Shida Irwana Omar

Annals of the University of Craiova, Economic Science Series, Vol 38 (3 / 2010), pag. 046

Ionut - Cosmin Băloi

We present in this study an original assessment of the development of tourism activities in Retezat National Park using the tourism area life cycle model. Understanding the development stages is imposed by social, economic, but also taking into account the perspective of environmental management found in the rising stage. A significant part is devoted to estimate the internal and external factors, the social, economical and environmental motivations. Research was conducted in a long time and by direct experimentation, the author travelling several times to document directly in the region. The results of TALC model application reveal that currently the National Park through the development stage. The conclusive issues refers to the exhibition of some development scenarios and the implications of strategic decisions that need to take account of lifecycle factors interferences in Retezat’s tourism development.

Prof. Konstantinos Andriotis

Muzzo (Muzaffer) Uysal

ERCAN AKKAYA

jayde russell

RELATED PAPERS

Adam R . Szromek

Journal of Travel Research

Pavlina Latkova

Tourism Planning & Development

Azizi Bahauddin , Shida Irwana Omar

Dan Musinguzi

Journal of Sustainable Tourism

Novie Afrillies

Journal of Tourism Sciences

Bernard M Kitheka , Elizabeth D Baldwin

Atwine Angel Gabriel

Duarte Morais

Indulal Soman

Manisa Piuchan

Journal of Sustainable Development

Rachel Dodds

Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities, Pertanika

Kadek Wiweka , Kadek Wiweka

Chaozhi Zhang

Bianca Biagi

Annals of Tourism Research

Brian Kermath

Roslyn Russell

Gemma Canoves

Marianna Sigala

Ioulia Poulaki , Professor Andreas Papatheodorou

Nicole B Hoffmann

Folia Turistica

Michał Żemła

Serafeim Polyzos

Biljana Petrevska , Noga Collins-Kreiner

Wieslaw Alejziak , Piotr Zmyślony , Sabina Owsianowska , Michał Żemła , Dorota Ujma

Journal of Mathematics and Statistics

Seyed A. Hamid Shobeiri Nejad

Journal of Environmental Management

Paolo Vassallo

Examining the Impacts of Tourism on Gumushane Residents According to the Doxey Index

Murat ÖDEMİŞ

Klari Czimre , olivier dehoorne , Corina Tatar

Mark Hampton

Dobrica Jovicic

Sergej Strajnak, Ph.D., LL.M.,

Haywantee Ramkissoon (PhD)

tendai r vhori

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Breadcrumbs

Butler’s tourism area life cycle and its expansion to the creative economy.

In 1980, R. W. Butler published his tourism area cycle of evolution model graphing a correlation of number of tourists on the y-axis and time on the x-axis. Although a location’s capacity for number of tourists and the specific number of sustainable years may vary from location to location, Butler proposed that every tourist location evolves through a common set of stages: exploration, involvement, development, consolidation, stagnation, and then some variation of rejuvenation or decline. Butler’s model frames the resources that enable a region to become a tourist destination as finite and ultimately exhaustible.

Rather than imagining a tourist destination always being a tourist destination, Butler recognizes that change is constant and that, ultimately, the initial reasons a location becomes a desirable tourist destination will no longer exist and the location will either need to seek rejuvenation or face decline. Embedded within Butler’s model is a call for sustainability and the conservation of resources, thereby increasing the length of time a location can maintain being a viable tourist destination. There is also an implicit call for closer collaboration and integration of the tourism industry and the local community to better shield the local community from potential exploitation or disenfranchisement.

Upload file

Link to publisher's page, suggested citation.

Hwang, Leo. 2017. "Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle and Its Expansion to the Creative Economy." The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Travel and Tourism . ed. Linda L. Lowry, SAGE Publications, Inc.

- 2030 Agenda

- Foro ALC 2030

- 75 Anniversary

- About ECLAC

Tourism life cycle, tourism competitiveness and upgrading strategies in the Caribbean

View publication

Press Enter to see the available file formats. Use Tab to choose one.

Description

In the 1980s Butler adapted the life cycle product model to the tourism industry and created the “Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) model”. The model recognizes six stages in the tourism product life cycle: exploration, investment, development, consolidation, stagnation and followed, after stagnation, by decline or revitalization of the product. These six stages can in turn be regrouped into four main stages. The Butler model has been applied to more than 30 country cases with a wide degree of success. De Albuquerque and Mc Elroy (1992) applied the TALC model to 23 small Caribbean island States in the 1990s. Following De Albuquerque and Mc Elroy, the TALC is applied to the 32 member countries of the Caribbean Tourism Organization (CTO) (except for Cancun and Cozumel) to locate their positions along their tourism life-cycle in 2007. This is done using the following indicators: the evolution of the level, market share and growth rate of stay-over arrivals; the growth rate and market share of visitor expenditures per arrival and the tourism styles of the destinations, differentiating between ongoing mass tourism and niche marketing strategies and among upscale, mid-scale and low-scale destinations. Countries have pursued three broad classes of strategies over the last 15 years in order to move upward in their tourism life cycle and enhance their tourism competitiveness. There is first a strategy that continues to rely on mass-tourism to build on the comparative advantages of “sun, sand and sea”, scale economies, all-inclusive packages and large amounts of investment to move along in Stage 2 or Stage 3 (Cuba, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico). There is a second strategy pursued mainly by very small islands that relies on developing specific niche markets to maintain tourism competitiveness through upgrading (Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, British Virgin Islands and Turks and Caicos), allowing them to move from Stage 2 to Stage 3 or Stage 3 to a rejuvenation stage. There is a third strategy that uses a mix of mass-tourism, niche marketing and quality upgrading either to emerge onto the intermediate stage (Trinidad and Tobago); avoid decline (Aruba, The Bahamas) or rejuvenate (Barbados, Jamaica and the United States Virgin Islands). There have been many success stories in Caribbean tourism competitiveness and further research should aim at empirically testing the determinants of tourism competitiveness for the region as a whole.

Table of contents

.--I. Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) Model and Concurrent Tourism Strategies.--II. Tourism Competitiveness and Tourism Performance in the Caribbean.--III. Tourism Life Cycle in the Caribbean: From Mass Tourism to Upgrading.--IV. Concluding Remarks

You might be interested in

Tourism in the Caribbean: competitiveness, upgrading, linkages and the role of public private...

CEPAL Review no.104

What kind of State? What kind of equality? XI Regional Conference on Women in Latin America and...

Ageing and development in a society for all ages

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Introduction and definition. The tourist area life cycle (Butler, Citation 1980) has been in existence for over four decades since its publication in The Canadian Geographer and was described by Hall and Butler (Citation 2006, p. xv) as 'one of the most cited and contentious areas of tourism knowledge….(and) has gone on to become one of the best known theories of destination growth and ...

Butler's Tourism Area Life Cycle Model is a simplistic linear model. Using a graph, it plots the different stages in tourism development in accordance with the x and y axis of tourist number growth and time. Within this, Butler's model demonstrates 6 stages of tourism development. OK, enough with the complicated terminology- lets break this ...

1. Introduction. Since Butler's original article (Butler, 1980) on tourism destination development, the tourism area life cycle (TALC) model has been extensively discussed and is generally accepted as a conceptual heuristic for understanding the evolution of tourism destinations (Pearce, 1989, Butler, 2006a, Butler, 2006b).The model assumes a sigmoidal life cycle in the growth of a tourism ...

A Creative Economy Cycle. One adaptation of Butler's tourism area cycle of evolution is to transfer similar concepts to the creative economy. A tourism economy plays hand in hand with the creative economy, and one can feed the other. Like Butler's tourism areas, artists and artisans, communities, villages, towns, cities, and counties also ...

The model developed by Butler in 1980, known as "Tourism Area Life Cycle," is the most cited. His theory takes the concept of product life cycle from marketing and applies its basic S-shaped curve. Butler bases his model on the growth in the number of tourists over time and identifies six phases (Figure 1): exploration (arrival of the first batch of tourists at a destination which has no ...

The concept of tourism area life cycle (TALC) implies that places as destinations, like products, follow a relatively consistent process of development and a recognizable cycle of evolution (Butler, 1980).The concept in its abstract form embodies the assumption that sooner or later a threshold is reached after which a tourist destination is perceived to decline in desirability.

He has published over twenty book and a hundred papers on tourism. A past president of the International Academy for the Study of Tourism, he was UNWTO Ulysses Laureate 2016. Richard Butler has researched tourism from a geographical perspective for over forty years in Canada and the UK. He is most well known for his adaptation of the life cycle ...

The Tourism Area Life Cycle model has been cited and used by academics and those in the industry for over 40 years. This book provides an overview of the contribution of the model, its strengths and weaknesses, and particularly its relevance in the 21st century. The final section considers revisions and concludes with a new version of the model.

The Tourism Area Life Cycle in the Twenty-First Century. Richard Butler, Richard Butler. Search for more papers by this author. Richard Butler, Richard Butler. Search for more papers by this author. Book Editor(s): Alan A. Lew, Alan A. Lew. Northern Arizona University, USA.

In the 1980s Butler adapted the life cycle product model to the tourism industry and created the "Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) model". The model recognizes six stages in the tourism product life cycle: exploration, investment, development, consolidation, stagnation and followed, after stagnation, by decline or revitalization of the product.

The development phase in the tourism life cycle is a critical turning point, where effective management can significantly influence the future trajectory of a destination. At this juncture, understanding the intricacies of the tourism life cycle allows for the implementation of strategies that balance growth with sustainability.

Summary of Butler's Tourism Area Life Cycle Model (TALC) In conclusion, Butler's Tourism Area Life Cycle Model (TALC) is a useful tool to understand the stages that a tourist attraction goes through in its life. It helps tourism planners and developers examine how tourist resorts can change over time in response to the changing demands of ...

It proposed that the life cycle of a tourist area could be divided into a number of stages (exploration, involvement, development, consolidation, stagnation, followed by a range of options from rejuvenation to decline), and the rather brief discussion noted the different characteristics of destinations at each of those stages.

Abstract. The five stages of Butler's tourism destination life cycle model are explained as well as the possible scenarios after these five stages. Similar concepts proposed by Fuster, years before the publication of Butler's model, are also discussed. Attempts to improve Butler's model and some criticisms of the model are also highlighted.

This paper examines the most influential model of tourism development, the life cycle model, which has defined a 'normal science' of evolution for tourism destinations. The model is internally coherent, logical, easily intelligible and was used extensively as a guide to predicting development. For all destinations it postulates a path of ...

The Tourism Area Life Cycle: Conceptual and theoretical issues. This book is divided into five sections: the conceptual origins of the TALC, spatial relationships and the TALC, alternative conceptual approaches, renewing or retiring with the TALC, and predicting with the TALC. It concludes with a review of the future potential of the model in ...

The study investigates the tourism development in Macedonia in the post-socialist period of the country, using the Butler (1980) Tourist Area Life Cycle (TALC) model as an analytical tool. The model provides a framework to explain the complex processes of the development and changes in tourism in the country over the years.

In 1980, R. W. Butler published his tourism area cycle of evolution model graphing a correlation of number of tourists on the y-axis and time on the x-axis. Although a location's capacity for number of tourists and the specific number of sustainable years may vary from location to location, Butler proposed that every tourist location evolves through a common set of stages: exploration ...

May 2020. Elyes Sahli. Butler's (1980) Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) is a widely used model to study the evolution of a particular tourism destination. The model suggests that a tourism area ...

A model is a simplification of the real world used to better understand reality. Professor Richard Butler suggested a model for the life cycle of a tourist destination which has a number of stages ...

Abstract. We provide a simple micro-foundation of the tourism area life cycle hypothesis, based on tourists' utility maximization. As a result of social interactions among tourists which determine destinations popularity, the market share of visitors which decides to visit a specific destination follows a logistic dynamics, consistent with ...

the "Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) model". The model recognizes six stages in the tourism. after stagnation, by decline or revitalization of the product. These six stages can in turn be regrouped. into four main stages. The Butler model has been applied to more than 30 country cases with a wide. degree of success.

Tourism booms lead to more jobs and opportunities in communities." ... The US' real-life treasure hunt. A tourist recently uncovered a 7.46-carat diamond in an Arkansas state park, but it turns ...

The tourist area life cycle (Butler, 1980) has been in existence for over four decades since its publication in The Canadian Geographer and was described by Hall and Butler (2006, p. xv) as 'one of the most cited and contentious areas of tourism knowledge.... (and) has gone on to become one of the best known theories of destination growth ...